Virtual Geomorphology Continued from Page 39

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

1 Recognising Glacial Features. Examine the Illustrations of Glacial Landforms That Are Shown on This Page and on the Next Page

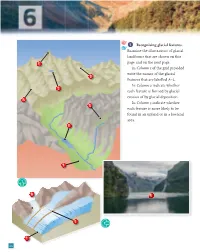

1 Recognising glacial features. Examine the illustrations of glacial landforms that are shown on this C page and on the next page. In Column 1 of the grid provided write the names of the glacial D features that are labelled A–L. In Column 2 indicate whether B each feature is formed by glacial erosion of by glacial deposition. A In Column 3 indicate whether G each feature is more likely to be found in an upland or in a lowland area. E F 1 H K J 2 I 24 Chapter 6 L direction of boulder clay ice flow 3 Column 1 Column 2 Column 3 A Arête Erosion Upland B Tarn (cirque with tarn) Erosion Upland C Pyramidal peak Erosion Upland D Cirque Erosion Upland E Ribbon lake Erosion Upland F Glaciated valley Erosion Upland G Hanging valley Erosion Upland H Lateral moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) I Frontal moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) J Medial moraine Deposition Lowland (upland also accepted) K Fjord Erosion Upland L Drumlin Deposition Lowland 2 In the boxes provided, match each letter in Column X with the number of its pair in Column Y. One pair has been completed for you. COLUMN X COLUMN Y A Corrie 1 Narrow ridge between two corries A 4 B Arête 2 Glaciated valley overhanging main valley B 1 C Fjord 3 Hollow on valley floor scooped out by ice C 5 D Hanging valley 4 Steep-sided hollow sometimes containing a lake D 2 E Ribbon lake 5 Glaciated valley drowned by rising sea levels E 3 25 New Complete Geography Skills Book 3 (a) Landform of glacial erosion Name one feature of glacial erosion and with the aid of a diagram explain how it was formed. -

Landform Studies in Mosedale, Northeastern Lake District: Opportunities for Field Investigations

Field Studies, 10, (2002) 177 - 206 LANDFORM STUDIES IN MOSEDALE, NORTHEASTERN LAKE DISTRICT: OPPORTUNITIES FOR FIELD INVESTIGATIONS RICHARD CLARK Parcey House, Hartsop, Penrith, Cumbria CA11 0NZ AND PETER WILSON School of Environmental Studies, University of Ulster at Coleraine, Cromore Road, Coleraine, Co. Londonderry BT52 1SA, Northern Ireland (e-mail: [email protected]) ABSTRACT Mosedale is part of the valley of the River Caldew in the Skiddaw upland of the northeastern Lake District. It possesses a diverse, interesting and problematic assemblage of landforms and is convenient to Blencathra Field Centre. The landforms result from glacial, periglacial, fluvial and hillslopes processes and, although some of them have been described previously, others have not. Landforms of one time and environment occur adjacent to those of another. The area is a valuable locality for the field teaching and evaluation of upland geomorphology. In this paper, something of the variety of landforms, materials and processes is outlined for each district in turn. That is followed by suggestions for further enquiry about landform development in time and place. Some questions are posed. These should not be thought of as being the only relevant ones that might be asked about the area: they are intended to help set enquiry off. Mosedale offers a challenge to students at all levels and its landforms demonstrate a complexity that is rarely presented in the textbooks. INTRODUCTION Upland areas attract research and teaching in both earth and life sciences. In part, that is for the pleasure in being there and, substantially, for relative freedom of access to such features as landforms, outcrops and habitats, especially in comparison with intensively occupied lowland areas. -

2480 ± 90 +1850 8570 NPL-72. Mockerkin Tarn, West Cumberland

[RADIOCARBON, VOL. 8, 1966, P. 340-347] NATIONAL PHYSICAL LABORATORY RADIOCARBON MEASUREMENTS IV I. HASSALL W. J. CALLOW, M. J. BAKER and GERALDINE National Physical Laboratory, Teddington, England The following list comprises measurements made since those re- ported in NPL III and is complete to the end of November 1965. Ages are relative to A.D. 1950 and are calculated using a half-life of 5568 yr. The measurements, corrected for fractionation (quoted 6013 values are relative to the P.D.B. standard), are referred to 0.950 times the activity of the NBS oxalic acid as contemporary reference standard. The quoted uncertainty is one standard deviation derived from a proper combination of the parameter variances as described in detail in NPL III. These variances are those of the standard and background measure- ments over a rolling twenty week period, of the sample C14 and 8013 measurements and of the de Vries effect (assumed to add an additional uncertainty equivalent to a standard deviation of 80 yr). Any uncertainty in the half-life has been excluded so that relative C14 ages may be cor- rectly compared. Absolute age assessments, however, should be made using the accepted best value for the half-life and the appropriate un- certainty then included. If the net sample count rate is less than 4 times the standard error of the difference between the sample and background count rates, a lower limit to the age is reported corresponding to a net sample count rate of 4 times the standard error of this difference. The description of each sample is based on information provided by the person submitting the sample to the laboratory. -

Quarrernary GEOLOGY of MINNESOTA and PARTS of ADJACENT STATES

UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Ray Lyman ,Wilbur, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. C. Mendenhall, Director P~ofessional Paper 161 . QUArrERNARY GEOLOGY OF MINNESOTA AND PARTS OF ADJACENT STATES BY FRANK LEVERETT WITH CONTRIBUTIONS BY FREDERICK w. SARDE;30N Investigations made in cooperation with the MINNESOTA GEOLOGICAL SURVEY UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE WASHINGTON: 1932 ·For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, Washington, D. C. CONTENTS Page Page Abstract ________________________________________ _ 1 Wisconsin red drift-Continued. Introduction _____________________________________ _ 1 Weak moraines, etc.-Continued. Scope of field work ____________________________ _ 1 Beroun moraine _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 47 Earlier reports ________________________________ _ .2 Location__________ _ __ ____ _ _ __ ___ ______ 47 Glacial gathering grounds and ice lobes _________ _ 3 Topography___________________________ 47 Outline of the Pleistocene series of glacial deposits_ 3 Constitution of the drift in relation to rock The oldest or Nebraskan drift ______________ _ 5 outcrops____________________________ 48 Aftonian soil and Nebraskan gumbotiL ______ _ 5 Striae _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ 48 Kansan drift _____________________________ _ 5 Ground moraine inside of Beroun moraine_ 48 Yarmouth beds and Kansan gumbotiL ______ _ 5 Mille Lacs morainic system_____________________ 48 Pre-Illinoian loess (Loveland loess) __________ _ 6 Location__________________________________ -

Landtype Associations (Ltas) of the Northern Highland Scale: 1:650,000 Wisconsin Transverse Mercator NAD83(91) Map NH3 - Ams

Landtype Associations (LTAs) of the Northern Highland Scale: 1:650,000 Wisconsin Transverse Mercator NAD83(91) Map NH3 - ams 212Xb03 212Xb03 212Xb04 212Xb05 212Xb06 212Xb01 212Xb02 212Xb02 212Xb01 212Xb03 212Xb05 212Xb03 212Xb02 212Xb 212Xb07 212Xb07 212Xb01 212Xb03 212Xb05 212Xb07 212Xb08 212Xb03 212Xb07 212Xb07 212Xb01 212Xb01 212Xb07 Landtype Associations 212Xb01 212Xb01 212Xb02 212Xb03 212Xb04 212Xb05 This map is based on the National Hierarchical Framework of Ecological Units 212Xb06 (NHFEU) (Cleland et al. 1997). 212Xb07 The ecological landscapes used in this handbook are based substantially on 212Xb08 Subsections of the NHFEU. Ecological landscapes use the same boundaries as NHFEU Sections or Subsections. However, some NHFEU Subsections were combined to reduce the number of geographical units in the state to a manageable Ecological Landscape number. LTA descriptions can be found on the back page of this map. County Boundaries 0 2.75 5.5 11 16.5 22 Miles Sections Kilometers Subsections 0 4 8 16 24 32 Ecological Landscapes of Wisconsin Handbook - 1805.1 WDNR, 2011 Landtype Association Descriptions for the Northern Highland Ecological Landscape 212Xb01 Northern Highland Outwash The characteristic landform pattern is undulating pitted and unpitted Plains outwash plain with swamps, bogs, and lakes common. Soils are predominantly well drained sandy loam over outwash. Common habitat types include forested lowland, ATM, TMC, PArVAa and AVVb. 212Xb02 Vilas-Oneida Sandy Hills The characteristic landform pattern is rolling collapsed outwash plain with bogs common. Soils are predominantly excessively drained loamy sand over outwash or acid loamy sand debris flow. Common habitat types include PArVAa, ArQV, forested lowland, AVVb and TMC. 212Xb03 Vilas-Oneida Outwash Plains The characteristic landform pattern is nearly level pitted and unpitted outwash plain with bogs and lakes common. -

Glacier Lake, Saddle, & Blue Ice Trails

Guide to Glacier Lake, Saddle, & Blue Ice Trails in Kachemak Bay State Park Trail Access: Glacier Spit, Saddle, or Humpy Creek Grewingk Tram Spur (1 mile, easy) Allowable Uses: Hiking This spur connects Glacier Distance: 3.2 mi one-way (Glacier Lake Trail) Lake Trail and Emerald Lake Loop Trail. There is a hand- 1.0 mi one way (Saddle Trail) operated cable car pulley 6.7 mi one-way (Glacier Spit to Blue Ice Trail end) system over Grewingk Elevation Gain: 200 ft (Glacier Lake Trail) Creek. Operation requires 200 ft (Glacier Lake to Saddle Trailhead) two people. Maximum capacity of the tram is 500 500 ft (Glacier Spit to Blue Ice Trail end) pounds. If only two people are crossing the Difficulty: Easy; family suitable (Glacier Lake Trail) tram, one person should stay behind and assist in Camping: Moderate (Saddle Trail) pulling the other across. Two people in the tram cart without assistance from others on the plat- Glacier Spit, Grewingk Glacier Lake, Grewingk Creek, Moderate (Blue Ice Trail) form is difficult. Gloves are helpful in operating Tarn Lake, Humpy Creek, Right Beach (accessible at Hiking Time: 1.5 hours (to end Glacier Lake Trail) low tide from Glacier Spit) the tram. 30 minutes (Saddle Trail) Water Availability: 5 hours (Glacier Spit to Blue Ice Trail end) Glacier Lake & Saddle Trails: Grewingk Creek (glacial), Grewingk Glacier Lake A Popular route joins the Saddle and Glacier Lake (glacial), small streams near glacier and on Saddle Tr. Blue Ice Trail: Trails. The Glacier Lake Trail follows flat terrain Safety and Considerations: This is the only developed access to Grewingk through stands of cottonwoods & spruce, and CAUTION: Unless properly trained and outfitted for Glacier. -

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota

Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Pleistocene Geology of Eastern South Dakota By RICHARD FOSTER FLINT GEOLOGICAL SURVEY PROFESSIONAL PAPER 262 Prepared as part of the program of the Department of the Interior *Jfor the development-L of*J the Missouri River basin UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE, WASHINGTON : 1955 UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Douglas McKay, Secretary GEOLOGICAL SURVEY W. E. Wrather, Director For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U. S. Government Printing Office Washington 25, D. C. - Price $3 (paper cover) CONTENTS Page Page Abstract_ _ _____-_-_________________--_--____---__ 1 Pre- Wisconsin nonglacial deposits, ______________ 41 Scope and purpose of study._________________________ 2 Stratigraphic sequence in Nebraska and Iowa_ 42 Field work and acknowledgments._______-_____-_----_ 3 Stream deposits. _____________________ 42 Earlier studies____________________________________ 4 Loess sheets _ _ ______________________ 43 Geography.________________________________________ 5 Weathering profiles. __________________ 44 Topography and drainage______________________ 5 Stream deposits in South Dakota ___________ 45 Minnesota River-Red River lowland. _________ 5 Sand and gravel- _____________________ 45 Coteau des Prairies.________________________ 6 Distribution and thickness. ________ 45 Surface expression._____________________ 6 Physical character. _______________ 45 General geology._______________________ 7 Description by localities ___________ 46 Subdivisions. ________-___--_-_-_-______ 9 Conditions of deposition ___________ 50 James River lowland.__________-__-___-_--__ 9 Age and correlation_______________ 51 General features._________-____--_-__-__ 9 Clayey silt. __________________________ 52 Lake Dakota plain____________________ 10 Loveland loess in South Dakota. ___________ 52 James River highlands...-------.-.---.- 11 Weathering profiles and buried soils. ________ 53 Coteau du Missouri..___________--_-_-__-___ 12 Synthesis of pre- Wisconsin stratigraphy. -

Glacier Mass Balance This Summary Follows the Terminology Proposed by Cogley Et Al

Summer school in Glaciology, McCarthy 5-15 June 2018 Regine Hock Geophysical Institute, University of Alaska, Fairbanks Glacier Mass Balance This summary follows the terminology proposed by Cogley et al. (2011) 1. Introduction: Definitions and processes Definition: Mass balance is the change in the mass of a glacier, or part of the glacier, over a stated span of time: t . ΔM = ∫ Mdt t1 The term mass budget is a synonym. The span of time is often a year or a season. A seasonal mass balance is nearly always either a winter balance or a summer balance, although other kinds of seasons are appropriate in some climates, such as those of the tropics. The definition of “year” depends on the measurement method€ (see Chap. 4). The mass balance, b, is the sum of accumulation, c, and ablation, a (the ablation is defined here as negative). The symbol, b (for point balances) and B (for glacier-wide balances) has traditionally been used in studies of surface mass balance of valley glaciers. t . b = c + a = ∫ (c+ a)dt t1 Mass balance is often treated as a rate, b dot or B dot. Accumulation Definition: € 1. All processes that add to the mass of the glacier. 2. The mass gained by the operation of any of the processes of sense 1, expressed as a positive number. Components: • Snow fall (usually the most important). • Deposition of hoar (a layer of ice crystals, usually cup-shaped and facetted, formed by vapour transfer (sublimation followed by deposition) within dry snow beneath the snow surface), freezing rain, solid precipitation in forms other than snow (re-sublimation composes 5-10% of the accumulation on Ross Ice Shelf, Antarctica). -

GLACIERS and GLACIATION in GLACIER NATIONAL PARK by J Mines Ii

Glaciers and Glacial ion in Glacier National Park Price 25 Cents PUBLISHED BY THE GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION IN COOPERATION WITH THE NATIONAL PARK SERVICE Cover Surveying Sperry Glacier — - Arthur Johnson of U. S. G. S. N. P. S. Photo by J. W. Corson REPRINTED 1962 7.5 M PRINTED IN U. S. A. THE O'NEIL PRINTERS ^i/TsffKpc, KALISPELL, MONTANA GLACIERS AND GLACIATTON In GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By James L. Dyson MT. OBERLIN CIRQUE AND BIRD WOMAN FALLS SPECIAL BULLETIN NO. 2 GLACIER NATURAL HISTORY ASSOCIATION. INC. GLACIERS AND GLACIATION IN GLACIER NATIONAL PARK By J Mines Ii. Dyson Head, Department of Geology and Geography Lafayette College Member, Research Committee on Glaciers American Geophysical Union* The glaciers of Glacier National Park are only a few of many thousands which occur in mountain ranges scattered throughout the world. Glaciers occur in all latitudes and on every continent except Australia. They are present along the Equator on high volcanic peaks of Africa and in the rugged Andes of South America. Even in New Guinea, which many think of as a steaming, tropical jungle island, a few small glaciers occur on the highest mountains. Almost everyone who has made a trip to a high mountain range has heard the term, "snowline," and many persons have used the word with out knowing its real meaning. The true snowline, or "regional snowline" as the geologists call it, is the level above which more snow falls in winter than can he melted or evaporated during the summer. On mountains which rise above the snowline glaciers usually occur. -

Brief Communication: Collapse of 4 Mm3 of Ice from a Cirque Glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina

The Cryosphere, 13, 997–1004, 2019 https://doi.org/10.5194/tc-13-997-2019 © Author(s) 2019. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Brief communication: Collapse of 4 Mm3 of ice from a cirque glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina Daniel Falaschi1,2, Andreas Kääb3, Frank Paul4, Takeo Tadono5, Juan Antonio Rivera2, and Luis Eduardo Lenzano1,2 1Departamento de Geografía, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Nacional de Cuyo, Mendoza, 5500, Argentina 2Instituto Argentino de Nivología, Glaciología y Ciencias Ambientales, Mendoza, 5500, Argentina 3Department of Geosciences, University of Oslo, Oslo, 0371, Norway 4Department of Geography, University of Zürich, Zürich, 8057, Switzerland 5Earth Observation research Center, Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, 2-1-1, Sengen, Tsukuba, Ibaraki 305-8505, Japan Correspondence: Daniel Falaschi ([email protected]) Received: 14 September 2018 – Discussion started: 4 October 2018 Revised: 15 February 2019 – Accepted: 11 March 2019 – Published: 26 March 2019 Abstract. Among glacier instabilities, collapses of large der of up to several 105 m3, with extraordinary event vol- parts of low-angle glaciers are a striking, exceptional phe- umes of up to several 106 m3. Yet the detachment of large nomenon. So far, merely the 2002 collapse of Kolka Glacier portions of low-angle glaciers is a much less frequent pro- in the Caucasus Mountains and the 2016 twin detachments of cess and has so far only been documented in detail for the the Aru glaciers in western Tibet have been well documented. 130 × 106 m3 avalanche released from the Kolka Glacier in Here we report on the previously unnoticed collapse of an the Russian Caucasus in 2002 (Evans et al., 2009), and the unnamed cirque glacier in the Central Andes of Argentina recent 68±2×106 and 83±2×106 m3 collapses of two ad- in March 2007. -

Inventory of Glaciers, Glacial Lakes and the Identification of Potential

Asia‐Pacific Network for Global Change Research Inventory of Glaciers, Glacial Lakes and the Identification of Potential Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) Affected by Global Warming in the Mountains of India, Pakistan and China/Tibet Autonomous Region Final report for APN project 2004-03-CMY-Campbell J. Gabriel Campbell (Ph.D.), Director General International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development G. P. O. Box 3226, Kathmandu, Nepal, [email protected] The following collaborators worked on this project: Prof. Xin Li (Ph. D.), Cold and Arid Regions Environmental and Engineering Research Institute, (CAREERI), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS), Lanzhou, P. R. China, [email protected] Mr. Gong Tongliang, Bureau of Hydrology Tibet Autonomous Region, Lhasa, P. R. China, [email protected] Dr. Tej Partap. CSK Himachal Pradesh Agricultural University, Palampur, Himachal Pradesh, India, [email protected] Prof. Dr. B. R. Arora, Wadia Institute of Himalayan Geology (WIHG), Department of Science & Technology, Government of India, Dehra Dun, Uttaranchal, India, [email protected] Dr. Badaruddin Soomro, Pakistan Agricultural Research Council (PARC), Islamabad, Pakistan, [email protected] Inventory of Glaciers and Glacial Lakes and the Identification of Potential Glacial Lake Outburst Floods (GLOFs) Affected by Global Warming in the Mountains of India, Pakistan and China/Tibet Autonomous Region 2004-03-CMY-Campbell Final Report submitted to APN J. Gabriel Campbell (Ph.D.) Director General, International Centre for Integrated Mountain -

Glaciation in East Africa

GLACIATION IN EAST AFRICA Glaciation: it refers to the overall effect of glaciers on the landscape resulting into both erosional and depositional features Glacier is a thick/large mass of ice of limited width, moving from the area of accumulation (snow field) following pre-existing valleys due to gravity. Or Glacier is an accumulated/compacted mass of ice/snow moving in a restricted channel/valley from a highland to a low land. Glaciers have different names for example mountain glaciers and valley glaciers/alpine glacier. Glaciers move continuously from higher ground to lower ground under the influence of gravity and are enclosed within the valley walls. The action of glacier includes glacier erosion, transportation and deposition. These processes will lead to the formation of glacier scenery. Glaciers in East Africa are only found in high mountainous areas of Kenya, Kilimanjaro and Rwenzori. This is mainly because those mountains (Kenya, Kilimanjaro and Rwenzori) are high above the snow line (4500m). In East Africa glacial activities are limited to a few places, this is due to a number of factors that limit the formation of snow and this include: The latitudinal position of East Africa across or astride the equator hence, the temperatures are generally hot and therefore not conducive for the existence of glacier anywhere and anyhow in East Africa. In East Africa the snowline is very high about 4800m, which only the three highest mountains can reach which explains them having the glacial activities. Snowline is that line where there is permanent snow and ice. It can be at ground level at poles.