Food Consumption Patterns and Nutrition Transition in South-East Asia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sensory and Nutritional Quality, Shelf-Life, and Microbial Analyses of Hermitically Sealed Chevon Products

Jonathan N. Nayga.et.al. Int. Journal of Engineering Research and Applications www.ijera.com ISSN: 2248-9622, Vol. 6, Issue 3, (Part - 6) March 2016, pp.15-19 RESEARCH ARTICLE OPEN ACCESS Sensory and Nutritional Quality, Shelf-Life, and Microbial Analyses of Hermitically Sealed Chevon Products Jonathan N. Nayga, Emelita B. Valdez, Mila R. Andres1, Beulah B. Estrada2, Emelina A. Lopez3, Rogelio B. Tamayo4, and Aubrey Joy M. Balbin5* 1Animal Science Department, College of Agriculture, Isabela State University, Echague, Isabela, 2Food Science Department, College of Engineering, ISU, 3Animal Products Development Center, Marulas, Valenzuela, 4Department of Animal Science, College of Agriculture, Cagayan State University, Lallo, Cagayan, and 5Research Department, ISU, Author of correspondence: [email protected] ABSTRACT Goat meat or chevon is regarded as nutritious food and became popular food for health conscious people. In the Philippines, demand for chevon is growing as noted in the increasing per capita consumption of chevon. However, the price of chevon remains high. With a goal to transform the basis of disposal from per head basis to retail scheme and to make it affordable to consumers, a study was conducted to use canning technology to develop chevon-based products. Using 11-month old male upgraded Boer, local dishes popularly cooked using chevon were innovated and elevated to capture wider market. These dishes include braised chevon in soy sauce and spices (locally known adobo), savory goat stew commonly in tomato stew (locally called kaldereta) and goat meat ceviche made with skin, smothered with vinegar and spices (known as kilawin) Sensory evaluation and different analyses such as nutritional, shelf-life and microbial were conducted for food safety. -

Catering Menu

49-10 Queens Blvd. Woodside, NY 11377 www.titorads.com Phone: (718) 205-7299 or (718) 205-7295 | Fax: (718) 205-4178 [email protected] Catering List Pork BBQ $2.50 each Chicken BBQ $2.50 each Ginisang sitaw, calabasa, okra $50.00 / tray Fresh Lumpia $2.50 each Ginataan sitaw, calabasa, okra $50.00 / tray Lumpia Shanghai $50.00 / tray Chopsuey $50.00 / tray Pritong Lumpia $35.00 / tray Bicol Express (vegetable) $50.00 / tray Calamari $65.00 / tray Bicol Express (meat) $60.00 / tray Camaron Rebosado $70.00 / tray Pancit Canton $40.00 / tray Sisig $60.00 / tray Bihon $40.00 / tray Crispy Pata $16.95 each Bam-i $45.00 / tray Lechon Kawali $60.00 / tray Palabok $50.00 / tray Adobo Pork $50.00 / tray Sotanghon $40.00 / tray Inihaw Pork $70.00 / tray Garlic Fried Rice $20.00 / tray Menudo $50.00 / tray Adobo Fried Rice $30.00 / tray Dinuguan $50.00 / tray Dried Fish Fried Rice $30.00 / tray Binagoongang Baboy $60.00 / tray Shanghai Fried Rice $30.00 / tray Fried Chicken $50.00 / tray Tito’s Chicken $50.00 / tray Tito’s Delight $35.00 / tray Chicken Afritada $50.00 / tray Leche Flan big tray $25.00 Chicken Inasal $50.00 / tray small tray $10.00 Chicken Kaldereta $50.00 / tray Cassava big tray $25.00 small tray $10.00 Chicken Curry $50.00 / tray Ube big tray $30.00 Chicken in Coconut Cream / small tray $10.00 Ginataan Manok $50.00 / tray Maja Blanca big tray $25.00 Turon $40.00 / tray Beef Mechado $75.00 / tray Beef Caldereta $75.00 / tray Glazed Ham $65.00 Beef Adobo $75.00 / tray Lechon Belly $70.00 Beef Steak (Filipino Style) $75.00 / tray Rellenong Manok $45.00 Kare-Kare $80.00 / tray Rellenong Bangus $25.00 Embotido (pork) $20.00 Sweet and Sour Tilapia Fillet $70.00 / tray Morcon (beef) 25.00 /$75.00 / tray Sweet and Sour Tuna Loin $70.00 / tray Kalderetang Kambing $75.00 Pinakbet $50.00 / tray Arroz Valenciana $60.00 Ampalaya con Carne $50.00 / tray Ampalaya con Hipon $50.00 / tray Spicy Laing $75.00 / tray Prices subject to change without prior notice. -

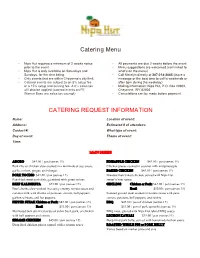

Catering Menu

Catering Menu • Nipa Hut requires a minimum of 2 weeks notice • All payments are due 2 weeks before the event prior to the event • Menu suggestions are welcomed (not limited to • Nipa Hut is only available on Saturdays and what’s on the menu) Sundays, for the time being • Call Merelyn directly at 307-214-2865 (leave a • Only events that are within Cheyenne’s city limit message or the best time to call is weekends or • Catered events are subject to an 8% setup fee after 5pm during the weekday) or a 15% setup and serving fee. A 6% sales tax • Mailing information: Nipa Hut, P.O. Box 20902, will also be applied (catered events on FE Cheyenne, WY 82003 Warren Base are sales tax exempt) • Cancelations can be made before payment CATERING REQUEST INFORMATION Name: Location of event: Address: Estimated # of attendees: Contact #: What type of event: Day of event: Theme of event: Time: MAIN DISHES ADOBO $45.00 / pan (serves 15) PINEAPPLE CHICKEN $45.00 / pan (serves 15) Pork ribs or chicken slow-cooked in a marinade of soy sauce, Chicken pieces cooked in coconut milk and pineapple garlic, onions, ginger, and vinegar. BAKED CHICKEN $45.00 / pan (serves 15) PORK TOCINO $45.00 / pan (serves 15) Breaded then baked chicken, served with Nipa Hut Pan-fried sweet pork dish, garnished with green onions sweet’n’sour sauce. BEEF KALDERETA $55.00 / pan (serves 15) GINILING Chicken or Pork: $45.00 / pan (serves 15) Beef chunks slow-cooked in a spicy creamy tomato sauce and Beef: $50.00 / pan (serves 15) coconut milk with chunks of potatoes, carrots, bell peppers, Sautéed ground meat cooked in tomato sauce with peas, garbanzo beans, and hot peppers. -

Manam-Menu-Compressed.Pdf

Manam prides itself in serving a wide variety of local comfort food. Here, we’ve taken on the challenge of creating edible anthems to Philippine cuisine. At Manam, you can find timeless classic meals side-by-side with their more contemporary renditions, in servings of various sizes. Our meals are tailored to suit the curious palates of this generation’s voracious diners. So make yourself comfortable at our dining tables, and be prepared for the feast we’ve got lined up. Kain na! E n s a la d a a n Classics g Twistsf K am a ti s & Ke son Pica-Pica Pica-Pica g Puti S M L s S M L g in Streetballs of Fish Tofu, Crab, & 145 255 430 Caramelized Patis Wings 165 295 525 R id Lobster with Kalye Sauce u q Pork Ear Kinilaw 150 280 495 gs r S in pe Beef Salpicao & Garlic 180 335 595 W ep is & P k Cheddar & Green Finger 95 165 290 at alt la P chy S k Gambas in Chilis, Olive Oil & Garlic 185 345 615 Chili Lumpia Lu d Crun la m e u p iz B ia l Baby Squid in Olive Oil & Garlic 160 280 485 ng e n Deep-Fried Chorizo & 145 265 520 B m o i a r Kesong Puti Lumpia co r a Crunchy Salt & Pepper Squid Rings 160 280 485 l a h E C c x i p h Lumpiang Bicol Express 75 130 255 r C Tokwa’t Baboy 90 160 275 e s s Fresh Lumpiang Ubod 75 125 230 Chicharon Bulaklak 235 420 830 G isin g G Dinuguan with Puto 170 295 595 is in g Balut with Salt Trio 65 110 170 Ensalada & Gulay Ensalada & Gulay S M L S M L Pinakbet 120 205 365 Adobong Bulaklak ng Kalabasa 120 205 365 Okra, sitaw, eggplant, pumpkin, Pumpkin flowers, fried tofu, tinapa an Ensalad g Namn tomatoes, pork bits, bagoong, -

11955 88Th Avenue Delta, BC

PARTY TRAYS Soup SINIGANG NA BABOY $13.95 Lumpiang Shanghai 50 pcs - $40 100 pcs - $75 Pork BBQ (cater size; min. 40 pcs) $2.95/piece Pork belly and mixed vegetables in sour tamarind soup .95 Chicken BBQ (cater size; min. 40 pcs) $2.95/piece SINIGANG NA BANGUS BELLY $14 Embutido $10/piece Boneless milkfish and mixed vegetables in sour tamarind soup Chicken Emapanadas $1.99/piece (min. 25pcs) SINIGANG NA BAKA $15.95 Pritong Lumpia (vegetarian) 25 pcs - $50 Beef short ribs and mixed vegetables in sour tamarind soup Bangus Sisig $12.50/piece (min. 5 pcs) SINIGANG NA CORNED BEEF *NEW* $15.95 Rellenong Bangus $35/piece House-cured corned beef chunks and mixed vegetables SMALL MEDIUM LARGE in sour tamarind soup 13” x 10” x 1.5” 13” x 10” x 2.5” 20.75” x 13” x 2” SINIGANG NA HIPON $15.95 Bicol Express 50 70 130 Shrimp and mixed vegetables in sour tamarind soup Bopis 50 70 130 BULALO $15.95 Cebu Lechon 70 90 160 Beef bone marrow soup with vegetables Crispy Binagoongan 60 80 150 NILAGA $15.95 Dinakdakan 60 80 150 Beef short ribs, potato and baby bokchoy soup Dinuguan 50 70 130 .95 BEEF PAPAITAN *NEW* $14 Lechon Kawali 60 80 150 Beef kamto brisket, tripe and tendon soup Lechon Paksiw 55 75 140 .95 CHICKEN MAMI $8 Menudo 50 70 130 Chicken noodle soup Pork Sisig 60 80 150 BEEF MAMI $10.50 Beef noodle soup Lechon Sisig 70 90 170 LOMI $8.95 Tokwa’t Baboy 55 75 140 Chicken, pork and shrimp in egg drop noodle soup Bistek Tagalog 80 100 180 GOTO $8.95 Kaldereta 70 90 170 Beef tripe and tendon congee Kare Kare 70 90 170 FILIPINO RESTAURANT AND CATERING -

University Centre

Infusion Menu Item FODMAP Ingredients to be Aware of Achari Beef Garlic Onion Yogurt Aloo Baingan Garlic Aloo Gobi Masala Garlic Onion Cauliflower Batter Fried Fish w/ Sauce Batter Mix Garlic Beef Cutlets Bread Crumbs Garlic Onion Beef Korma Garlic Onions Yogurt Beet Poriyal Beets Coconut Urad Dal Beetroot Curry Beets Garlic Mango Powder Onion Urad Dal Bhindi Masala Garlic Onion Mango Powder Broccoli and Water Chestnuts Baby corn Broccoli Celery Garlic Onion Vegetable base Butter Paneer Butter Curry Sauce Cauliflower Cream Cabbage and Bacon Stir Fry Celery Garlic Onion Cabbage and Dal Garlic Onion Split Peas Carrot and Beans Poriyal Coconut Onion Urad Dal Channa Masala Chickpeas Garlic Onion Chicken Afritada Garlic Green Peas Onion Chicken Shahi Cashewnuts Coconut Cream Garlic Onion Yogurt Chicken Sinigang Garlic Onion Chopsuey Cauliflower Baby corn Celery Garlic Leeks Mushroom Peas Coconut Crusted Fish w/ Creamy Chilli Lime Coconut Sauce Coconut Flour Garlic Crispy Fried Chicken w/ Sauce Garlic Powder Dal Fry Garlic Onion Toor Tal Fillipino Pork Adobo Onion Garlic Fish Curry Garlic Onion Gulai Telur Garlic Onion Hot and Sour Fish Garlic Onion Sambal Kaldereta Garlic Green Peas Onions Kheema Aloo Matar Garlic Green Peas Onion Kimchi Onion Garlic Flour Korean Chicken Wings Flour Garlic Onion Lamb Darbari Garlic Onions Yogurt Cashew Paste Lamb Hariyali Onions Yogurt Garlic Lamb Karahi Garlic Onions Yogurt Lamb Rendang Onions Garlic Mixed Vegetable Jafrezi Peas Onion Mushroom Cauliflower Baby corn Garlic Mushroom Pepper Fry Mushroom Garlic -

Appetizers – Pulutan

APPETIZERS – PULUTAN • LUMPIA SHANGHAI – Your choice of PORK OR CHICKEN, . Served with Spicy Sweet & Sour sauce or Cane Vinegar Garlic dipping sauce. 9.95 • SEAFOOD GINATAANG KUHOL - (REAL ESCARGOT / CULTURED SNAILS) Sauteed in garlic, onions, ginger and coconut milk. Served on a wonderful coconut base broth with chili leaves and fresh baby spinach. 13. 5 SEASONAL (Gluten Free) • SEAFOOD CALAMARES – BREADED SQUID SERVED WIT H COCKTAIL OR TARTAR SAUCE 13.50 SEASONAL • ONE MEDIUM CRISPY PATA/ PORK HOCK - deep fried pork hock / PIGS FEET Crispilicious skin outside and tender and juicy on the inside. - 18.75 ( GF) • PORK TOKWA AT LECHON –Fried tofu & Lechon kawali (Crispy pork belly) topped with soy sauce and Cane Vinegar. 13.95 (Gluten Free) • PORK TOKWA AT TENGA – Fried tofu & steamed pigs ears ) topped with soy sauce and Cane Vinegar. 14.95 (Gluten Free) • PORK SIZZLING PORK SISIG – A traditional Filipino method of preparing sizzling pork. Marinated with ginger, onions, soy sauce, vinegar, lemon, and jalapeno. Twice cooked, griddled then, chopped and griddled again. Topped with a touch of mayonnaise. 13. 95 Add two eggs for 2.5 Specify if you want mild, medium or spicy (We only use quality lean pork meat) (Excellent as a main entrée also) • SIZZLING CHICKEN SISIG – Sisig has been one of the best creations in Filipino cuisine. Marinated with ginger, onions, soy sauce, vinegar, lemon, and jalapeno. Twice cooked, griddled then, chopped and griddled again. Topped with a touch of mayonnaise. 13. 95 Add two eggs for 2.5 Specify if you want mild, medium or spicy • PORK SIZZLING SISIG PIG EARS – Cooked SISIG style. -

Goldilocks Website Menu

Appete Cerritos / 562-865-11 Calamari - Crispy-friend squid, served with our garlic and vinegar sauce. Lumpiang Shanghai - Crispy mini springrolls filled with diced pork, shrimp and spices. Complemented with our signature sweet and sour sauce. Crispy Chicken Wings - Marinated and seasoned, crispy fried Lumpia Shanghai chicken wings. Available in Plain, Garlic, Sweet & Spicy, or Salt & Pepper. Tokwa’t Baboy - Fried tofu mixed with cirspy lechon bits and served with a garlic vingar sauce. Soups Bulalo Bangus Belly Sinigang - Sour soup made with boneless milkfish and tamarind. Pork Spare Ribs Sinigang - Sour soup made with pork spare ribs and tamarind. Bulalo Soup - A hearty beef shank soup with green beans, napa cabbage, potatoes, and sliced carrots. Dinuguan Pok Dinuguan - A unique combination of pork meat and entrails cooked in pork blood, vinegar, and spices. Crispy Binagoongan Crispy Dinuguan - A twist on an old favorite! Crispy pork meat and entrails, cooked in prok blood, vinegar, and spices. Lechon Kawali - Crispy-fried marinated pork belly served with our special liver sauce. Lechon Paksiw - Sliced pork belly deep-fried in liver broth and seasoned with vinegar and black pepper. Crispy Binagoongan - A scrumptious combination of bagoong, sauteed lechon kawali, diced fresh mangoes, and tomatoes. TociWOWsilog Available with eggplant. Crispy Lechon Kare-Kare Crispy Pata - Crispy-fried marinated pork hocks served with a garlic vinegar sauce. Beakfast Tapsilog Pinoy Breakfast Sampler - Fried boneless bangus (milkfish), stir-fried beef (tapa), stir-fried pork sausages (longanisa) with garlic fried rice, salted eggs, and diced tomatoes. Serves -4. Tapsilog - Beef tapa, garlic fried rice, and egg. Tocilog - Pork marinated and cured in vinegar, sugar, and Longsilog special spices Served with two eggs any style; garlic fried rice TociWOWsilog Longsilog - Sweet sausage served with eggs any style, garlic fried rice or Pan de Sal. -

Appetizers Breakfast

Appetizers LUMPIANG SHANGHAI | 8.50 Ground pork and vegetable spring rolls. CALAMARES | 10.95 Fried breaded squid. PRITONG LUMPIA | 2.25 per piece Fried vegetable spring roll. FRESH LUMPIA | 8.50 Fresh vegetable roll with house special garlic sauce topped with peanuts. ENSALADANG TALONG | 7.50 Grilled eggplant, salted duck egg and tomato salsa with shrimp paste. TOKWA’T BABOY | 9.95 Fried tofu and pork belly with soy vinegar sauce. UKOY | 8.50 Deep fried vegetable fritters FRIED SIOMAI | 7.50 Crispy fried shrimp and pork siomai stuffed with quail egg. KWEK KWEK | 7.50 Deep fried quail egg fritters. Breakfast PORKSILOG | 12.95 Sweet pork sausages with egg and garlic rice. BEEFSILOG | 12.50 House-cured corned beef with egg and garlic rice. TAPSILOG | 11.50 Garlic cured beef with egg and garlic rice. TOCILOG | 11.50 House-cured diced pork with egg and garlic rice. CHICKEN TOCILOG | 11.50 House-cured chicken with egg and garlic rice. LONGSILOG | 11.50 Sweet pork sausages with egg and garlic rice. BANGSILOG | 10.95 Crispy fried milkfish with egg and garlic rice. DAINGSILOG | 10.50 Dried fish (biya) with egg and garlic rice. Grilled PORK BBQ | 4.25 House special marinated pork barbecue. CHICKEN BBQ | 4.25 House special marinated chicken barbecue. CHICKEN INASAL | 12.50 Flame grilled lemongrass chicken served with chicken oil. LIEMPO | 12.95 Grilled pork belly. INIHAW NA TILAPIA | 11.50 Flame grilled tilapia. INIHAW NA PAMPANO | 16.50 Flame grilled pompano. GRILLED SQUID | 16.50 Two whole grilled squid. DINAKDAKAN | 12.95 Ilocano specialty grilled pork in ginger vinegar sauce. -

EVENTS with a DIFFERENCE at Novotel and Mercure Darwin Airport INTRODUCTION

EVENTS WITH A DIFFERENCE at Novotel and Mercure Darwin Airport INTRODUCTION WHY DARWIN FOR YOUR NEXT EVENT? Novotel and Mercure Darwin Airport is your ideal function venue in Darwin. Our flexible facilities make planning your next function effortless. Guests of both hotels enjoy access to nine distinctive venues offering unmatched flexibility for small and large gatherings. We listen to you so no matter the type of occasion we have the capability to make it a success. Our years of experience mean we can offer experienced staff and supporting audio visual technology. Conveniently located by the International Airport, Marrara Sports Complex and TIO Stadium. In addition to the assistance of a dedicated conference team from start to finish, the Darwin Airport Hotels offer a complimentary airport shuttle service, 24-hour guest services and special packages for meeting rooms and accommodation. We specialise in YOU! BREAKFAST Cossies Poolside Bar and Bistro offers an amazing selection of hot and cold buffet breakfast items for the perfect start to the day. QUICK START BREAKFAST $20 pp Minimum 15 pax • Seasonal sliced fruits • Assorted mini Danishes • Croissants • Homemade muffins • Condiments • Orange juice • Freshly brewed tea and coffee CONTINENTAL BREAKFAST $27 pp Minimum 25 pax • Seasonal sliced fruit • Smoked salmon • Individual yoghurt pots • Virgina ham • Toast and spreads • Hard boiled eggs • Assorted cereal • Cheddar cheese • Assorted mini Danishes • Assorted juices • Croissants • Freshly brewed tea and coffee • Homemade muffins Minimum -

Goldilocks Website Menu

Union City / 510-477-8881 Saa Pno Combo Meals Combo Combo Meal 1 - Fresh Lumpia, Pork BB, Empanaditas Combo Meal 2 - Pancit Palabok, Pork BB, Empanaditas Combo Meal - Dinuguan, Puto Cheese Combo Meal 4 - Pork BB, Siopao (Pork and Chicken are available), Soda Combo 4 Combo Meal 5 - Pork BB, Empanaditas, Soda Combo 1 Combo 2 Combo 5 Sde Dshes Pork Siopao - Steamed bun filled with sweet and savory pork asado. Chicken Siopao - Steamed bun filled with sweet and savory chicken asado. Chicken Empanada Pork Siomai - Juicy pork dumplings steamed to perfection and Siopao served with soy sauce and lemon. Dessets Chicken Empananda Cake Roll Slices Leche Flan - Rich and creamy creme caramel flavored with lemon zest. Beveaes Canned Soda Buko Juice Calamansi Juice Choco Iced Roll / Mango Juice Brazo de Mercedes Thst Quenches Sago’t Gulaman - Tapioca pearls and gelatin cubes with caramel, topped with crushed ice. Taho - Soy bean curd with tapioca pearls bathed in our lightly sweetened caramel sauce. Special Halo-Halo Pork Pork BB - Grilled marinated pork on a skewer and brushed with our signature barbecue sauce. Dinuguan - A unique combination of pork meat and entrails cooked in pork blood, vinegar, and spices. Paksiw na Lechon - Sliced pork belly deep-fried in liver broth and seasoned with vinegar and black pepper. Bopis - Diced pork sauteed with onions, bell peppers; slowly Pork BB simmered in tomato sauce, vinegar, and spices. Dinakdakan Dinakdakan Pork Binagoongan Beef Dinuguan Pinapaitan - A Filipino soup with slices of beef tripe and innards simmered with bile, vinegar, and spices. Pork Binagoongan Beef Kaldereta - Beef sauteed with bell peppers, green peas, pressed liver, and cheese in a spicy tomato sauce. -

305-454-0135 PEMBROKE PINES: 954-435-2772 Noodles Pork Pansit Bihon $35.00 Pork BB

LUTONG PINOY FILIPINO CUISINE CATERING MIAMI: 305-454-0135 PEMBROKE PINES: 954-435-2772 Noodles Pork Pansit Bihon $35.00 Pork BBQ $55.00 Pansit Sotanghon $35.00 (per stick) Regular $2.50 Pansit Canton $40.00 Sotanghon Soup $30.00 Lumpiang Shanghai (50pcs) $40.00 Palabok $40.00 Lechon Kawali $50.00 Pansit Malabon $40.00 Crispy Pata (chopped) $50.00 Spaghetti $40.00 Sisig $55.00 Pansit Molo $35.00 Embotido (per piece) $9.00 Pansit Bihon-Canton $35.00 Dinuguan $60.00 Pansit Canton-Sotanghon $35.00 Menudo $50.00 Vegetables Paksiw na Lechon $55.00 Pinakbet $40.00 Pochero $45.00 Chopseuy $45.00 Binagoongan $50.00 Adobong Kangkong $40.00 Paksiw na Pata $50.00 Laing $45.00 Igado $50.00 Ginataang Langka $50.00 Adobo $50.00 Ginataang Sitaw at Kalabasa $40.00 Afritada $50.00 Ampalaya Con Carne $45.00 Humba $50.00 Ginisang Ampalaya $40.00 Kare Kare (Pata) $50.00 Ginisang Sayote $35.00 Tokwa't Baboy $45.00 Ginisang Upo $35.00 Picadillo $45.00 Lumpiang Sariwa (per piece) $4.99 Pork chop Inihaw $50.00 Tortang talong (per piece) $3.99 Pork Kilawin $50.00 Lumpiang Toge (per piece) $2.00 Dinakdakan $50.00 Ginisang Monggo $30.00 Pork KareKare $50.00 Lumpia Hubad $45.00 Bicol Express $50.00 Chicken (Bone In) Desserts Fried Chicken $35.00 Chicken Afritada $45.00 Leche Flan $10.00 Chicken Adobo $45.00 Cassava Cake $40.00 Chicken Pastel $45.00 Ginataang Bilo-Bilo $35.00 Chicken Pochero $45.00 Ginataang Mais $30.00 Chicken Pineapple $45.00 Ginataang Monggo $30.00 Chicken Kaldereta $45.00 Kuchinta (50 pcs.) $35.00 Chicken Curry $45.00 Puto (50 pcs.) $35.00 Chicken