ABSTRACT a Descriptive Study of Protective Tissue Formation In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Differentiation of Epidermis with Reference to Stomata

Unit : 3 Differentiation of Epidermis with Reference to Stomata LESSON STRUCTURE 3.0 Objective 3.1 Introduction 3.2 Epidermis : Basic concept, its function, origin and structure 3.3 Stomatal distribution, development and classification. 3.4 Questions for Exercise 3.5 Suggested Readings 3.0 OBJECTIVE The epidermis, being superficial or outermost layer of cells, covers the entire plant body. It includes structures like stomata and trichomes. Distribution of stomata in epidermis depends on Ontogeny, number of subsidiary cells, separation of guard cells and different taxonomic ranks (classes, families and species). 3.1 INTRODUCTION The internal organs of plants are covered by a well developed tissue system, the epidermal or integumentary system. The epidermis modifies itself to cope up with natural surroundings, since, it is in direct contact with the environment. It protects the inner tissues from any adverse natural calamities like high temperature, desiccation, mechanical injury, excessive illumination, external infection etc. In some plants epidermis may persist throughout the life, while in others it is replaced by periderm. Although the epiderm usually arises from the outer most tunica layer, which thus coincides with Hanstein’s dermatogen, the underlying tissues may have their origin in the tunica or the corpus or both, depending on plant species and the number of tunica layers, explained by Schmidt (1924). ( 38 ) Differentiation of Epidermis with Reference to Stomata 3.2 EPIDERMIS Basic Concept The term epidermis designates the outer most layer of cells on the primary plant body. The word is derived from two Greek words ‘epi’ means upon and ‘derma’ means skin. Through the history of development of plant morphology the concept of the epidermis has undergone changes, and there is still no complete uniformity in the application of the term. -

Stoma and Peristomal Skin Care: a Clinical Review Early Intervention in Managing Complications Is Key

WOUND WISE 1.5 HOURS CE Continuing Education A series on wound care in collaboration with the World Council of Enterostomal Therapists Stoma and Peristomal Skin Care: A Clinical Review Early intervention in managing complications is key. ABSTRACT: Nursing students who don’t specialize in ostomy care typically gain limited experience in the care of patients with fecal or urinary stomas. This lack of experience often leads to a lack of confidence when nurses care for these patients. Also, stoma care resources are not always readily available to the nurse, and not all hospitals employ nurses who specialize in wound, ostomy, and continence (WOC) nursing. Those that do employ WOC nurses usually don’t schedule them 24 hours a day, seven days a week. The aim of this article is to provide information about stomas and their complications to nurses who are not ostomy specialists. This article covers the appearance of a normal stoma, early postoperative stoma complications, and later complications of the stoma and peristomal skin. Keywords: complications, ostomy, peristomal skin, stoma n 46 years of clinical practice, I’ve encountered article covers essential information about stomas, many nurses who reported having little educa- stoma complications, and peristomal skin problems. Ition and even less clinical experience with pa- It is intended to be a brief overview; it doesn’t provide tients who have fecal or urinary stomas. These exhaustive information on the management of com- nurses have said that when they encounter a pa- plications, nor does it replace the need for consulta- tient who has had an ostomy, they are often un- tion with a qualified wound, ostomy, and continence sure how to care for the stoma and how to assess (WOC) nurse. -

Chapter 5: the Shoot System I: the Stem

Chapter 5 The Shoot System I: The Stem THE FUNCTIONS AND ORGANIZATION OF THE SHOOT SYSTEM PRIMARY GROWTH AND STEM ANATOMY Primary Tissues of Dicot Stems Develop from the Primary Meristems The Distribution of the Primary Vascular Bundles Depends on the Position of Leaves Primary Growth Differs in Monocot and Dicot Stems SECONDARY GROWTH AND THE ANATOMY OF WOOD Secondary Xylem and Phloem Develop from Vascular Cambium Wood Is Composed of Secondary Xylem Gymnosperm Wood Differs from Angiosperm Wood Bark Is Composed of Secondary Phloem and Periderm Buds Are Compressed Branches Waiting to Elongate Some Monocot Stems Have Secondary Growth STEM MODIFICATIONS FOR SPECIAL FUNCTIONS THE ECONOMIC VALUE OF WOODY STEMS SUMMARY ECONOMIC BOTANY: How Do You Make A Barrel? 1 KEY CONCEPTS 1. The shoot system is composed of the stem and its lateral appendages: leaves, buds, and flowers. Leaves are arranged in different patterns (phyllotaxis): alternate, opposite, whorled, and spiral. 2. Stems provide support to the leaves, buds, and flowers. They conduct water and nutrients and produce new cells in meristems (shoot apical meristem, primary and secondary meristems). 3. Dicot stems and monocot stems are usually different. Dicot stems tend to have vascular bundles distributed in a ring, whereas in monocot stems they tend to be scattered. 4. Stems are composed of the following: epidermis, cortex and pith, xylem and phloem, and periderm. 5. Secondary xylem is formed by the division of cells in the vascular cambium and is called wood. The bark is composed of all of the tissues outside the vascular cambium, including the periderm (formed from cork cambium) and the secondary phloem. -

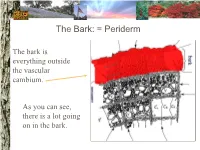

The Bark: = Periderm

The Bark: = Periderm The bark is everything outside the vascular cambium. As you can see, there is a lot going on in the bark. The Bark: periderm: phellogen (cork cambium): The phellogen is the region of cell division that forms the periderm tissues. Phellogen development influences bark appearance. The Bark: periderm: phellem (cork): Phellem replaces the epidermis as the tree increases in girth. Photosynthesis can take place in some trees both through the phellem and in fissures. The Bark: periderm: phelloderm: Phelloderm is active parenchyma tissue. Parenchyma cells can be used for storage, photosynthesis, defense, and even cell division! The Bark: phloem: Phloem tissue makes up the inner bark. However, it is vascular tissue formed from the vascular cambium. The Bark: phloem: sieve tube elements: Sieve tube elements actively transport photosynthates down the stem. Conifers have sieve cells instead. The cambium: The cambium is the primary meristem producing radial growth. It forms the phloem & xylem. The Xylem (wood): The xylem includes everything inside the vascular cambium. The Xylem: a growth increment (ring): The rings seen in many trees represent one growth increment. Growth rings provide the texture seen in wood. The Xylem: vessel elements: Hardwood species have vessel elements in addition to trachieds. Notice their location in the growth rings of this tree The Xylem: fibers: Fibers are cells with heavily lignified walls making them stiff. Many fibers in sapwood are alive at maturity and can be used for storage. The Xylem: axial parenchyma: Axial parenchyma is living tissue! Remember that parenchyma cells can be used for storage and cell division. -

Redalyc.Stem and Root Anatomy of Two Species of Echinopsis

Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad ISSN: 1870-3453 [email protected] Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México México dos Santos Garcia, Joelma; Scremin-Dias, Edna; Soffiatti, Patricia Stem and root anatomy of two species of Echinopsis (Trichocereeae: Cactaceae) Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad, vol. 83, núm. 4, diciembre, 2012, pp. 1036-1044 Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Distrito Federal, México Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=42525092001 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative Revista Mexicana de Biodiversidad 83: 1036-1044, 2012 DOI: 10.7550/rmb.28124 Stem and root anatomy of two species of Echinopsis (Trichocereeae: Cactaceae) Anatomía de la raíz y del tallo de dos especies de Echinopsis (Trichocereeae: Cactaceae) Joelma dos Santos Garcia1, Edna Scremin-Dias1 and Patricia Soffiatti2 1Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso do Sul, CCBS, Departamento de Biologia, Programa de Pós Graduação em Biologia Vegetal Cidade Universitária, S/N, Caixa Postal 549, CEP 79.070.900 Campo Grande, MS, Brasil. 2Universidade Federal do Paraná, SCB, Departamento de Botânica, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Botânica, Caixa Postal 19031, CEP 81.531.990 Curitiba, PR, Brasil. [email protected] Abstract. This study characterizes and compares the stem and root anatomy of Echinopsis calochlora and E. rhodotricha (Cactaceae) occurring in the Central-Western Region of Brazil, in Mato Grosso do Sul State. Three individuals of each species were collected, fixed, stored and prepared following usual anatomy techniques, for subsequent observation in light and scanning electronic microscopy. -

Tree Anatomy Stems and Branches

Tree Anatomy Series WSFNR14-13 Nov. 2014 COMPONENTSCOMPONENTS OFOF PERIDERMPERIDERM by Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care Warnell School of Forestry & Natural Resources, University of Georgia Around tree roots, stems and branches is a complex tissue. This exterior tissue is the environmental face of a tree open to all sorts of site vulgarities. This most exterior of tissue provides trees with a measure of protection from a dry, oxidative, heat and cold extreme, sunlight drenched, injury ridden site. The exterior of a tree is both an ecological super highway and battle ground – comfort and terror. This exterior is unique in its attributes, development, and regeneration. Generically, this tissue surrounding a tree stem, branch and root is loosely called bark. The tissues of a tree, outside or more exterior to the xylem-containing core, are varied and complexly interwoven in a relatively small space. People tend to see and appreciate the volume and physical structure of tree wood and dismiss the remainder of stem, branch and root. In reality, tree life is focused within these more exterior thin tissue sets. Outside of the cambium are tissues which include transport cells, structural support cells, generation cells, and cells positioned to help, protect, and sustain other cells. All of this life is smeared over the circumference of a predominately dead physical structure. Outer Skin Periderm (jargon and antiquated term = bark) is the most external of tree tissues providing protection, water conservation, insulation, and environmental sensing. Periderm is a protective tissue generated over and beyond live conducting and non-conducting cells of the food transport system (phloem). -

Anatomical Traits Related to Stress in High Density Populations of Typha Angustifolia L

http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/1519-6984.09715 Original Article Anatomical traits related to stress in high density populations of Typha angustifolia L. (Typhaceae) F. F. Corrêaa*, M. P. Pereiraa, R. H. Madailb, B. R. Santosc, S. Barbosac, E. M. Castroa and F. J. Pereiraa aPrograma de Pós-graduação em Botânica Aplicada, Departamento de Biologia, Universidade Federal de Lavras – UFLA, Campus Universitário, CEP 37200-000, Lavras, MG, Brazil bInstituto Federal de Educação, Ciência e Tecnologia do Sul de Minas Gerais – IFSULDEMINAS, Campus Poços de Caldas, Avenida Dirce Pereira Rosa, 300, CEP 37713-100, Poços de Caldas, MG, Brazil cInstituto de Ciências da Natureza, Universidade Federal de Alfenas – UNIFAL, Rua Gabriel Monteiro da Silva, 700, CEP 37130-000, Alfenas, MG, Brazil *e-mail: [email protected] Received: June 26, 2015 – Accepted: November 9, 2015 – Distributed: February 28, 2017 (With 3 figures) Abstract Some macrophytes species show a high growth potential, colonizing large areas on aquatic environments. Cattail (Typha angustifolia L.) uncontrolled growth causes several problems to human activities and local biodiversity, but this also may lead to competition and further problems for this species itself. Thus, the objective of this study was to investigate anatomical modifications on T. angustifolia plants from different population densities, once it can help to understand its biology. Roots and leaves were collected from natural populations growing under high and low densities. These plant materials were fixed and submitted to usual plant microtechnique procedures. Slides were observed and photographed under light microscopy and images were analyzed in the UTHSCSA-Imagetool software. The experimental design was completely randomized with two treatments and ten replicates, data were submitted to one-way ANOVA and Scott-Knott test at p<0.05. -

Eudicots Monocots Stems Embryos Roots Leaf Venation Pollen Flowers

Monocots Eudicots Embryos One cotyledon Two cotyledons Leaf venation Veins Veins usually parallel usually netlike Stems Vascular tissue Vascular tissue scattered usually arranged in ring Roots Root system usually Taproot (main root) fibrous (no main root) usually present Pollen Pollen grain with Pollen grain with one opening three openings Flowers Floral organs usually Floral organs usually in in multiples of three multiples of four or five © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 1 Reproductive shoot (flower) Apical bud Node Internode Apical bud Shoot Vegetative shoot system Blade Leaf Petiole Axillary bud Stem Taproot Lateral Root (branch) system roots © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 2 © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 3 Storage roots Pneumatophores “Strangling” aerial roots © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 4 Stolon Rhizome Root Rhizomes Stolons Tubers © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 5 Spines Tendrils Storage leaves Stem Reproductive leaves Storage leaves © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 6 Dermal tissue Ground tissue Vascular tissue © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 7 Parenchyma cells with chloroplasts (in Elodea leaf) 60 µm (LM) © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 8 Collenchyma cells (in Helianthus stem) (LM) 5 µm © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 9 5 µm Sclereid cells (in pear) (LM) 25 µm Cell wall Fiber cells (cross section from ash tree) (LM) © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 10 Vessel Tracheids 100 µm Pits Tracheids and vessels (colorized SEM) Perforation plate Vessel element Vessel elements, with perforated end walls Tracheids © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. 11 Sieve-tube elements: 3 µm longitudinal view (LM) Sieve plate Sieve-tube element (left) and companion cell: Companion cross section (TEM) cells Sieve-tube elements Plasmodesma Sieve plate 30 µm Nucleus of companion cell 15 µm Sieve-tube elements: longitudinal view Sieve plate with pores (LM) © 2014 Pearson Education, Inc. -

+ Complex Tissues

+ Complex Tissues ! Complex tissues are made up of two or more cell types. ! Xylem - Chief conducting tissue for water and minerals absorbed by the roots. ! Vessels - Made of vessel elements. ! Long tubes open at each end. ! Tracheids - Tapered at the ends with pits that allow water passage between cells. ! Rays - Lateral conduction. + Complex Tissues - Xylem ! Tracheids ! Long, thin cells with pointed ends that conduct water vertically ! Line up in columns like pipes by overlapping their tapered ends ! die when reach maturity ! Water conducted through tubes made up of tracheid cell walls ! Wherever two ends join, small holes in the cell wall called pits line up to allow water to flow from one tracheid to another. + Complex Tissues - Xylem ! Pits always occur in pairs so that a pair of pits lines up on either side of the middle lamella, or center layer, of the cell wall. + Complex Tissues - Xylem !Vessel elements !barrel-shaped cells with open ends that conduct water vertically. !line up end to end forming columns, called vessels, that conduct water. !Some have completely open ends, while others have narrow strips of cell wall material that partially covers the ends !Die at maturity, like tracheids. + Complex Tissues - Xylem ! Ray cells………. ! Long lived parenchyma cells that extend laterally like the spokes of a wheel from the center of a woody stem out towards the exterior of the stem ! alive at maturity ! Transport materials horizontally from center outward + Complex Tissues - Xylem ! Xylem fibers – ! long, thin sclerenchyma cells ! Xylem parenchyma cells- that run parallel to the ! Living cells vessel element ! Distributed among tracheids and vessels ! Help strengthen and support xylem ! Store water and nutrients + Complex Tissues - Phloem ! Phloem brings sugar [glucose from photosynthesis] from the leaves to all parts of the plant body. -

Tree Anatomy Stems and Branches

Tree Anatomy: STEM COMPONENTS Dr. Kim D. Coder, Professor of Tree Biology & Health Care, Warnell School, UGA Trees attempt to occupy more space and control available resources through cell divisions and cell expansion. From the end of a shoot tip to the end of a root tip, trees elongate. Along this axis of growth, trees also expand radially, which is termed “secondary growth.” Tree growth is initiated in the shoot tips (growing points / buds), root tips, vascular cambium (i.e. or simply cambium), and phellogen which generates periderm. The first two meristems are primary generation systems and the second two are termed secondary meristems. Cambial activity and xylem formation, as seen as visible increases in growth increment volume are radial growth, and reviewed here. Cross-Section Tree stem anatomy is usually visualized in cross-section. In this form, two-demensional “layers” or “rings,” and tissue types can be identified. More difficult is to visualize these two-dimensional cross- sections and incorporate them into a three dimensional object which changes and grows over time. Moving from outside to inside a stem, tissues encountered include those associated with periderm, secondary cortex, phloem, xylem, and pith. A traditional means of describing a mature tree stem cross-section defines which tissue type is cut first, second and third using a handsaw. A list of generic tissues in stems from outside to inside could include: Figure 1. epidermis and primary cortex = exterior primary protective tissues quickly rent, torn, and discarded with secondary growth (expansion of girth by lateral meristems – vascular cambium and phellogen). periderm = a multiple layer tissue responsible for tree protection and water conservation generated over the exterior of a tree from shoot to root, and produced by the phellogen (cork cambium – lateral meristem). -

Petrified Wood: the Anatomy of Arborescent Plant Life Through Time

The Anatomy of Arborescent Plant Life Through Time Mike Viney Collectors of petrified wood focus on permineralized plant material related to arborescent (tree-like) plant life. Evidence for the first fossil forest occurs in the Devonian. Fossil forest composition changes through geologic time, reflecting variety in evolutionary strategies for constructing a tree form. It is helpful and informative to study the anatomy of various trunk designs. Evolutionary adaptations for trunk structure can be recognized by the arrangement of tissues and organs. A quick survey of plant organs and tissues will enhance our discussion of the various evolutionary strategies for constructing a tree form. Plants are made of four types of organs: roots, stems, leaves, and reproductive structures. In turn, these organs are composed of three basic tissue systems: the ground tissue system, the vascular tissue system, and the dermal tissue system. Ground tissues including parenchyma, collenchyma and sclerenchyma are involved in photosynthesis, storage, secretion, transport, and structure. Parenchyma tissue produces all other tissues. Living parenchyma cells are involved in photosynthesis, storage, secretion, regeneration and in the movement of water and food. Parenchyma cells are typically spherical to cube shaped. Collenchyma tissue provides structural support for young growing organs. Living collenchyma cells are elongated cylinders and help to make up the familiar string-like material in celery stalks and leaf petioles. Sclerenchyma tissue provides support for primary and secondary plant bodies. Sclerenchyma cells often have lignified secondary walls and lack protoplasm at maturity. Elongated slender sclerenchyma cells known as fibers make up well known fibrous material such as hemp, jute, and flax. -

Cork Cambium - Produces Cork (Outer Most Layer of Bark) Pine Tree W/ 8 Cotyledons!

Plantae Seed Plants Vascular Plants • Formation of vascular tissue – Xylem (water) – Phloem (food) – True leaves, roots, and stems • Lignin • ____________ generation dominate Alternation of Generation Alternation of Generation • Sporophyte dependent on gametophyte – mosses • Large sporophyte and small independent gametophyte – ferns • Gametophyte dependent on sporophyte – seed plants Why be Sporophyte Dominant? • Reduced mutations – UV light harmful to DNA – Diploid (2n) form copes better with mutations • two alleles Why Retain Gametophyte Generation? • Ability to screen alleles – doesn’t require a large amount of energy • Sporophyte embryos rely on some gametophyte tissue Seeds • A seed is a sporophyte in a package – spores are only single cells – packaged with food • All seed plants are _____________ (more than one kind of spore) – megasporangia – microsporangia From Ovule to Seed Develops from megaspore Whole structure Embryo, food supply, protective coat Overview of Seed Plants • Produce Seeds – Can remain dormant for years – Pollination replaces swimming sperm • Gametophyte generation reduced – Gymnosperms lack antheridium – Angiosperms lack both archegonium and antheridium Phylogeny Gymnosperms (Naked Seed) • Division: Cycadophyta • Division: Ginkgophyta • Division: Gnetophyta • Division: Coniferophyta Ginkgophyta • Ginkgo or Maidenhair Tree • Characteristic leaves • Only one species • Only ______ are planted Cycadophyta • Cycads • Palm-like plants – Sago Palms • Leaves in cluster at top of trunks • True __________ Gnetophyta • 3