This Article Appeared in a Journal Published by Elsevier. the Attached

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

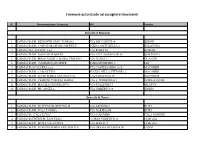

Farmacie Autorizzate Ad Accogliere Tirocinanti

Farmacie autorizzate ad accogliere tirocinanti N° Denominazione Farmacia VIA Località Distretto di Macomer 1 FARMACIA DR. DEMONTIS GIOV. TOMASO VIA DEI CADUTI 14 BIRORI 2 FARMACIA DR. CAPPAI GRAZIANO MICHELE P.ZZA CORTE BELLA 3 BOLOTANA 3 FARMACIA CADEDDU s.a.s. VIA ROMA 56 BORORE 4 FARMACIA DR. BIANCHI ALBERTO VIA VITT. EMANUELE 56 BORTIGALI 5 FARMACIA DR. PIRAS ANGELA MARIA CRISTINA VIA DANTE 1 DUALCHI 6 FARMACIA DR. GAMMINO GIUSEPPE P.ZZA MUNICIPIO 3 LEI 7 FARMACIA SCALARBA s.a.s. VIA CASTELSARDO 12/A MACOMER 8 FARMACIA DR. CABOI LUIGI PIAZZA DELLA VITTORIA 2 MACOMER 9 FARMACIA DR. SECHI MARIA ANTONIETTA VIA SARDEGNA 59 MACOMER 10 FARMACIA DR. CHERCHI TOMASO MARIA VIA E. D'ARBOREA 1 NORAGUGUME 11 FARMACIA DR. MASALA GIANFRANCO VIA STAZIONE 13 SILANUS 12 FARMACIA DR. PIU ANGELA VIA UMBERTO 88 SINDIA Distretto di Nuoro 1 FARMACIA DR. BUFFONI GIUSEPPINA M. VIA ASPRONI 9 BITTI 2 FARMACIA DR. TOLA TONINA VIA GARIBALDI BITTI 3 FARMACIA "CALA LUNA" VIA COLOMBO CALA GONONE 4 FARMACIA EREDI DR. FANCELLO CORSO UMBERTO 13 DORGALI 5 FARMACIA DR. MURA VALENTINA VIA MANNU 1 DORGALI 6 FARMACIA DR. BUFFONI MARIA ANTONIETTA VIA GRAZIA DELEDDA 80 FONNI 7 FARMACIA DR. MEREU CATERINA VIA ROMA 230 GAVOI 8 FARMACIA DR. SEDDA GIANFRANCA LARGO DANTE ALIGHIERI 1 LODINE 9 FARMACIA DR. PIRAS PIETRO VIA G.M.ANGIOJ LULA 10 FARMACIA DR. FARINA FRANCESCO SAVERIO VIA VITT. EMANUELE MAMOIADA 11 FARMACIA SAN FRANCESCO di Luciana Canargiu VIA SENATORE MONNI 2 NUORO 12 FARMACIA DADDI SNC di FRANCESCO DADDI e C. PIAZZA VENETO 3 NUORO 13 FARMACIA DR. -

Pollen Ontogeny Comparison of Natural Male-Fertile Diploid and Male-Sterile Triploid Lilium Lancifolium in Korea

J. AMER.SOC.HORT.SCI. 140(6):550–561. 2015. Pollen Ontogeny Comparison of Natural Male-Fertile Diploid and Male-Sterile Triploid Lilium lancifolium in Korea Gyeong Ran Do Fruit Division, National Institute of Horticultural and Herbal Science, Rural Development Administration, Nongsaengmyeong-ro, 100, Jeonju, Republic of Korea; and Environmental Horticulture, University of Seoul, Seoulsiripdaro 163, Seoul, Republic of Korea Ju Hee Rhee1 National Agrobiodiversity Center, National Academy of Agricultural Science, Rural Development Administration, Nongsaengmyeong-ro, 370, Jeonju, Republic of Korea; and Bioversity International, P.O. Box 236, UPM Post Office, Serdang, Selangor Darul Ehsan 43400, Malaysia Wan Soon Kim Environmental Horticulture, University of Seoul, Seoulsiripdaro 163, Seoul, Republic of Korea Yun Im Kang Floriculture Research Division, National Institute of Horticultural and Herbal Science, Rural Development Administration, Nongsaengmyeong-ro 100, Jeonju, Republic of Korea In Myung Choi, Jeom Hwa Han, Hyun Hee Han, Su Hyun Ryu, and Han Chan Lee Fruit Division, National Institute of Horticultural and Herbal Science, Rural Development Administration, Nongsaengmyeong-ro, 100, Jeonju, Republic of Korea ADDITIONAL INDEX WORDS. polyploidy, pollen development, fertility, abnormal tetrad ABSTRACT. Lilium lancifolium (syn. L. tigrinum) is the only polyploidy-complex species involving both diploid (2n =2x = 24) and triploid (2n =3x = 36) plants in the genus. The origin of natural triploid remains a mystery and research has been limited mainly to chromosomal studies that have overlooked research on pollen ontogeny. By spatiotemporal comparison of the development and morphology of diploid and triploid pollen grains, we study the correlations between pollen fertility and morphological development in diploid and triploid plants and propose the necessity and importance of further research on natural polyploid-ontogenetic diversity. -

ROSIDAE V SC.ROSIDAE V, 3 Órdenes, 12 Fam

ROSIDAE V SC.ROSIDAE V, 3 Órdenes, 12 Fam. GERANIALES herbáceas G leñosas G SAPINDALES APIALES G ROSALES O. Sapindales, Fam SAPINDACEAE Drupa Serjania Allophyllus edulis “chal-chal” Drupa Flores % Trisámara Disco nectarífero Sapindus saponaria “palo jabón” O. Sapindales, Fam HIPOCASTANACEAE Infl. paniculada K(5) C5 Flores % %, K(5), C5,A6-9, G Cápsula erizada Aesculus hippocastaneum “Castaño de las Indias” O.Sapindales, Fam. ACERACEAE Acer negundo “arce” Flores Flores Disámara Acer rubrum Acer palmatum Acer saccharum “maple sugar” O. Sapindales, Fam ZIGOPHYLLACEAE Larrea “jarillas” Pcia Monte Estípulas Larrea nitida Larrea cuneifolia Larrea divaricata O. Sapindales, Fam ZIGOPHYLLACEAE Bulnesia retama “retamo” Bulnesia sarmientoi “palo santo” O. Sapindales, Fam ANACARDIACEAE Infl. panoja Disco nectarífero C5 K5 Schinus aerira “aguaribay” Diagrama floral Canal resinífero en tallo Falso pimiento Drupa Canal resinífero foliar O. Sapindales, Fam ANACARDIACEAE Schinopsis quebracho colorado “quebracho colorado santiagueño” Schinopsis Schinopsis haenkeana “horco quebracho” Schinopsis balansae Durmientes Sámara “quebracho colorado chaqueño” O. Sapindales, Fam ANACARDIACEAE Pistacia vera “pistacho” Mangifera indica “mango” Anacardium occidentale “cajú o marañon” Drupa Drupa nuez receptáculo O. Sapindales, Fam SIMAROUBACEAE Disco Quassia amara nectarífero Ailanthus altissima “arbol del cielo Cápsula alada O. Sapindales, Fam MELIACEAE Melia azedarach “paraiso” Cedrela fisilis “cedro misionero” A() Disco nectarífero Cápsula c/ semillas aladas Drupa Infl. panoja O. Sapindales, Fam RUTACEAE C5 HESPERIDIO A() () K5 Citrus C.aurantium C.paradici “nararanjo agrio” “pomelo” C.limon “limón” C.reticulata “mandarino” C.sinensis Poncirus trifoliata “naranjo dulce” O. Sapindales, Fam RUTACEAE Balfourodendron riedelianum “guatambú” Sierras de Córdoba madera Sámara Fagara coco “cocucho” Schinus sp. y Schinopsis sp. Selva Misiones Cápsula Disco nectarífero Hojas compuestas c/aguijones Folículo Ruta chalepensis “ruda” O. -

The Triassic and Jurassic Sedimentary Cycles in Central Sardinia

Geological Field Trips Società Geologica Italiana 2016 Vol. 8 (1.1) ISPRA Istituto Superiore per la Protezione e la Ricerca Ambientale SERVIZIO GEOLOGICO D’ITALIA Organo Cartografico dello Stato (legge N°68 del 2-2-1960) Dipartimento Difesa del Suolo ISSN: 2038-4947 The Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary cycles in Central Sardinia: stratigraphy, depositional environment and relationship between tectonics and sedimentation 85° Congresso Nazionale della Società Geologica Italiana - Sassari, 2008 DOI: 10.3301/GFT.2016.01 The Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary cycles in Central Sardinia: stratigraphy, depositional environment and relationship between tectonics and sedimentation L. G. Costamagna - S. Barca GFT - Geological Field Trips geological fieldtrips2016-8(1.1) Periodico semestrale del Servizio Geologico d'Italia - ISPRA e della Società Geologica Italiana Geol.F.Trips, Vol.8 No.1.1 (2016), 78 pp., 54 figs. (DOI 10.3301/GFT.2016.01) The Triassic and Jurassic sedimentary cycles in Central Sardinia: stratigraphy, depositional environment and relationship between tectonics and sedimentation 85° Congresso Nazionale della Società Geologica Italiana, Sassari 6-8 settembre 2010 Luca G. Costamagna*, Sebastiano Barca** * Dipartimento di Scienze Chimiche e Geologiche, Via Trentino, 51 - 09127, Cagliari (Italy) ** Via P. Sarpi, 18 - 09131, Cagliari (Italy) Corresponding Author e-mail address: [email protected] Responsible Director Claudio Campobasso (ISPRA-Roma) Editorial Board Editor in Chief Gloria Ciarapica (SGI-Perugia) M. Balini, G. Barrocu, C. Bartolini, 2 Editorial Responsible D. Bernoulli, F. Calamita, B. Capaccioni, Maria Letizia Pampaloni (ISPRA-Roma) W. Cavazza, F.L. Chiocci, R. Compagnoni, D. Cosentino, Technical Editor S. Critelli, G.V. Dal Piaz, C. D'Ambrogi, Mauro Roma (ISPRA-Roma) P. -

Appendix Color Plates of Solanales Species

Appendix Color Plates of Solanales Species The first half of the color plates (Plates 1–8) shows a selection of phytochemically prominent solanaceous species, the second half (Plates 9–16) a selection of convol- vulaceous counterparts. The scientific name of the species in bold (for authorities see text and tables) may be followed (in brackets) by a frequently used though invalid synonym and/or a common name if existent. The next information refers to the habitus, origin/natural distribution, and – if applicable – cultivation. If more than one photograph is shown for a certain species there will be explanations for each of them. Finally, section numbers of the phytochemical Chapters 3–8 are given, where the respective species are discussed. The individually combined occurrence of sec- ondary metabolites from different structural classes characterizes every species. However, it has to be remembered that a small number of citations does not neces- sarily indicate a poorer secondary metabolism in a respective species compared with others; this may just be due to less studies being carried out. Solanaceae Plate 1a Anthocercis littorea (yellow tailflower): erect or rarely sprawling shrub (to 3 m); W- and SW-Australia; Sects. 3.1 / 3.4 Plate 1b, c Atropa belladonna (deadly nightshade): erect herbaceous perennial plant (to 1.5 m); Europe to central Asia (naturalized: N-USA; cultivated as a medicinal plant); b fruiting twig; c flowers, unripe (green) and ripe (black) berries; Sects. 3.1 / 3.3.2 / 3.4 / 3.5 / 6.5.2 / 7.5.1 / 7.7.2 / 7.7.4.3 Plate 1d Brugmansia versicolor (angel’s trumpet): shrub or small tree (to 5 m); tropical parts of Ecuador west of the Andes (cultivated as an ornamental in tropical and subtropical regions); Sect. -

Through Our French Window Gordon James

©Gordon James ©Gordon Through our French window Gordon James Fig. 1 Asphodelus ramosus n 2014 I wrote an article above the hamlet of Le attention – systematically I for this journal about Clapier where we have a perhaps, dealing with the the orchids that grow on small house, and covers an Ranunculaceae family first, and around a limestone area of perhaps 25km2 lying but that could prove a little plateau in Southern France 750–850m above sea level dull; or perhaps according to called the Plateau du which, together with the season. In the end I decided Guilhaumard, which is surrounding countryside, simply to pick out some of situated on the southern supports an extraordinarily our favourites. With a few edge of the great Causse rich range of plants besides exceptions all the plants du Larzac, a limestone orchids. mentioned in this article karst plateau in the south I wasn’t sure how best can be reached on foot from of the Massif Central. to introduce the plants our house by moderately fit Guilhaumard rises steeply I think deserve special pensioners like us! ©Gordon James ©Gordon James ©Gordon Fig. 2 Asphodelus ramosus Fig. 3 Narcissus assoanus 371 ©Gordon James ©Gordon James ©Gordon Fig. 4 Narcissus poeticus Fig. 5 Iris lutescens Despite its elevation, I will start with those summers are hot, as the plants which, at least for a Plateau is relatively far moment, carpet the ground toward the South of and foremost amongst these ©Gordon James ©Gordon France, though it can be is Asphodelus ramosus (syn. quite cold and snowy A. -

Nightshade”—A Hierarchical Classification Approach to T Identification of Hallucinogenic Solanaceae Spp

Talanta 204 (2019) 739–746 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Talanta journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/talanta Call it a “nightshade”—A hierarchical classification approach to T identification of hallucinogenic Solanaceae spp. using DART-HRMS-derived chemical signatures ∗ Samira Beyramysoltan, Nana-Hawwa Abdul-Rahman, Rabi A. Musah Department of Chemistry, State University of New York at Albany, 1400 Washington Ave, Albany, NY, 12222, USA ARTICLE INFO ABSTRACT Keywords: Plants that produce atropine and scopolamine fall under several genera within the nightshade family. Both Hierarchical classification atropine and scopolamine are used clinically, but they are also important in a forensics context because they are Psychoactive plants abused recreationally for their psychoactive properties. The accurate species attribution of these plants, which Seed species identifiction are related taxonomically, and which all contain the same characteristic biomarkers, is a challenging problem in Metabolome profiling both forensics and horticulture, as the plants are not only mind-altering, but are also important in landscaping as Direct analysis in real time-mass spectrometry ornamentals. Ambient ionization mass spectrometry in combination with a hierarchical classification workflow Chemometrics is shown to enable species identification of these plants. The hierarchical classification simplifies the classifi- cation problem to primarily consider the subset of models that account for the hierarchy taxonomy, instead of having it be based on discrimination between species using a single flat classification model. Accordingly, the seeds of 24 nightshade plant species spanning 5 genera (i.e. Atropa, Brugmansia, Datura, Hyocyamus and Mandragora), were analyzed by direct analysis in real time-high resolution mass spectrometry (DART-HRMS) with minimal sample preparation required. -

Medicinal Plants in the High Mountains of Northern Jordan

Vol. 6(6), pp. 436-443, June 2014 DOI: 10.5897/IJBC2014.0713 Article Number: 28D56BF45309 ISSN 2141-243X International Journal of Biodiversity Copyright © 2014 Author(s) retain the copyright of this article and Conservation http://www.academicjournals.org/IJBC Full Length Research Paper Medicinal plants in the high mountains of northern Jordan Sawsan A. Oran and Dawud M. Al- Eisawi Department of Biological Sciences, Faculty of Sciences, University of Jordan, Amman, Jordan. Receive 10 April, 2014; Accepted 24 April, 2014 The status of medicinal plants in the high mountains of northern Jordan was evaluated. A total of 227 plant species belonging to 54 genera and 60 families were recorded. The survey is based on field trips conducted in the areas that include Salt, Jarash, Balka, Amman and Irbid governorates. Line transect method was used; collection of plant species was done and voucher specimens were deposited. A map for the target area was provided; the location of the study area grids in relation to their governorate was included. Key words: Medicinal plants, high mountains of northern Jordan, folk medicine. INTRODUCTION Human beings have always made use of their native cinal plant out of 670 flowering plant species identified in flora, not just as a source of nutrition, but also for fuel, the same area in Jordan. Recent studies are published medicines, clothing, dwelling and chemical production. on the status of medicinal plants that are used fofolk Traditional knowledge of plants and their properties has medicine by the local societies (Oran, 2014). always been transmitted from generation to generation Medicinal plants in Jordan represent 20% of the total through the natural course of everyday life (Kargıoğlu et flora (Oran et al., 1998). -

Ruta Essential Oils: Composition and Bioactivities

molecules Review Ruta Essential Oils: Composition and Bioactivities Lutfun Nahar 1,* , Hesham R. El-Seedi 2, Shaden A. M. Khalifa 3, Majid Mohammadhosseini 4 and Satyajit D. Sarker 5,* 1 Laboratory of Growth Regulators, Institute of Experimental Botany ASCR & Palacký University, Šlechtitel ˚u27, 78371 Olomouc, Czech Republic 2 Biomedical Centre (BMC), Pharmacognosy Group, Department of Pharmaceutical Biosciences, Uppsala University, Box 591, SE-751 24 Uppsala, Sweden; [email protected] 3 Department of Molecular Biosciences, The Wenner-Gren Institute, Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden; [email protected] 4 Department of Chemistry, College of Basic Sciences, Shahrood Branch, Islamic Azad University, Shahrood, Iran; [email protected] 5 Centre for Natural Products Discovery (CNPD), School of Pharmacy and Biomolecular Sciences, Liverpool John Moores University, James Parsons Building, Byrom Street, Liverpool L3 3AF, UK * Correspondence: [email protected] (L.N.); [email protected] (S.D.S.); Tel.: +44-(0)-1512312096 (S.D.S.) Abstract: Ruta L. is a typical genus of the citrus family, Rutaceae Juss. and comprises ca. 40 different species, mainly distributed in the Mediterranean region. Ruta species have long been used in traditional medicines as an abortifacient and emmenagogue and for the treatment of lung diseases and microbial infections. The genus Ruta is rich in essential oils, which predominantly contain aliphatic ketones, e.g., 2-undecanone and 2-nonanone, but lack any significant amounts of terpenes. Three Ruta species, Ruta chalepensis L., Ruta graveolens L., and Ruta montana L., have been extensively studied for the composition of their essential oils and several bioactivities, revealing their potential medicinal and agrochemical applications. -

Cross‑Reactivity Between Parietaria Judaica and Parietaria Officinalis in Immunotherapy Extracts for the Treatment of Allergy to Parietaria

326 BIOMEDICAL REPORTS 12: 326-332, 2020 Cross‑reactivity between Parietaria judaica and Parietaria officinalis in immunotherapy extracts for the treatment of allergy to Parietaria NatalY CANCELLIERE1, IRENE IGLESIAS2, ÁNGEL AYUGA1 and Ernesto ENRIQUE MIRANDA2 1Medical Department, MERCK SLU, 28006 Madrid; 2Department of Allergology, Hospital of Sagunto, 46520 Valencia, Spain Received July 11, 2019; Accepted January 2, 2020 DOI: 10.3892/br.2020.1297 Abstract. Parietaria judaica and P. officinalis are the two Introduction most common subspecies of the Parietaria genus. P. judaica and P. officinalis have exhibited cross-reactivity in previous Allergic rhinitis (AR) is a symptomatic disorder of the nose studies. P. judaica pollen is the main cause of allergy in the induced by an IgE‑mediated inflammation following allergen Mediterranean area. It has been shown that a high percentage exposure of the membranes lining the nose (1). Due to its of patients sensitized to P. judaica with allergic rhinitis (AR) increasing prevalence worldwide (2,3), including up to 22% have an increased risk of developing asthma. The present study in Spain (3,4), and the burden of symptoms impacting on the aimed to confirm the cross‑reactivity between P. judaica and general well-being and health-related quality of life of patients P. officinalis and to evaluate the use of a single P. officinalis suffering from this condition, AR represents a serious global extract in patients allergic to both subspecies as a preferable health problem (5). AR and asthma frequently coexist, sharing option for the diagnosis and treatment of allergy in a highly a number of physiopathologic links and risk factors, including pollinated area of the Spanish Mediterranean coast. -

The Seed Atlas of Pakistan-Xi. Urticaceae

Pak. J. Bot ., 47(3): 987-994, 2015. THE SEED ATLAS OF PAKISTAN-XI. URTICACEAE RUBINA ABID *, AFSHEEN ATHER AND M. QAISER Department of Botany, University of Karachi, Karachi-75270, Pakistan. *Corresponding author’s e-mail: [email protected] Abstract Seed morphology and its numerical analysis of the 9 taxa belonging to the family Urticaceae carried out with the help of scanning electron microscopy. Seed micro and macro morphological characters were significantly helpful to trace the phenetic relationship between the taxa of the family Urticaceae. Key words: Seed morphology, Phenetic relationship, Urticaceae, Pakistan. Introduction microscopy dry seeds were directly mounted on metallic stub using double adhesive tape and coated with gold for The family Urticaceae is commonly known as a period of 6 minutes in sputtering chamber and Nettle family, comprises 1050 species distributed in 48 observed under SEM. The terminology used is in genera mostly found in tropical regions few species are accordance to Lawrence (1970), Radford et al. (1974) also reported from temperate zones (Mabberley, 2008). and Stearn (1983) with slight modifications. Numerical In Pakistan the family Urticaceae is represented by 9 analysis was carried out to recognize the relationship species distributed in 6 genera viz., Forsskalea L., and dissimilarities of species within the family Lecanthus Wedd., Parietaria L., Pilea Lindl., Pouzolzia Urticaceae. Hierarchical clustering was performed by Gaudich and Urtica L. including 9 taxa (Ghafoor, 1981). using Euclidean distance index with the computer There are various reports available where seed package (Anon., 2012). Each taxon was treated as morphological data was significantly used to reveal the operational taxonomic unit (OTU). -

Testing Testing

Testing…testing… Background information Summary Students perform an experiment Most weeds have a variety of natural to determine the feeding enemies. Not all of these enemies make preferences of yellow admiral good biocontrol agents. A good biocontrol caterpillars. agent should feed only on the target weed. It should not harm crops, natives, Learning Objectives or other desirable plants, and it must not Students will be able to: become a pest itself. With this in mind, • Explain why biocontrol agents when scientists look for biocontrol agents, are tested before release. they look for “picky eaters”. • Describe how biocontrol agents are tested before Ideally, a biocontrol agent will be release. monophagous—eating only the target weed. Sometimes, however, an organism Suggested prior lessons that is oligophagous—eating a small What is a weed? number of related plants—is also a good Cultivating weeds agent, particularly when the closely related plants are also weeds. Curriculum Connections Science Levels 5 & 6 In order to test the safety of a potential biocontrol agent, scientists offer a variety Vocabulary/concepts of plants to the agent in the laboratory Choice test, no choice test, and/or in the field. They choose plants repeated trials, control, economic that are closely related to the target threshold weed, as these are the most likely plants to be attacked. The non-target plants Time tested may be crops, native plants, 30-45 minutes pre-experiment ornamentals, or even other weeds. The discussion and set-up tests are designed to answer two main 30-45 minutes data collection questions: and discussion 1.