Geographic Variation in the Advertisement Calls of Hyla Eximia and Its Possible Explanations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Other Contributions

Other Contributions NATURE NOTES Amphibia: Caudata Ambystoma ordinarium. Predation by a Black-necked Gartersnake (Thamnophis cyrtopsis). The Michoacán Stream Salamander (Ambystoma ordinarium) is a facultatively paedomorphic ambystomatid species. Paedomorphic adults and larvae are found in montane streams, while metamorphic adults are terrestrial, remaining near natal streams (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). Streams inhabited by this species are immersed in pine, pine-oak, and fir for- ests in the central part of the Trans-Mexican Volcanic Belt (Luna-Vega et al., 2007). All known localities where A. ordinarium has been recorded are situated between the vicinity of Lake Patzcuaro in the north-central portion of the state of Michoacan and Tianguistenco in the western part of the state of México (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). This species is considered Endangered by the IUCN (IUCN, 2015), is protected by the government of Mexico, under the category Pr (special protection) (AmphibiaWeb; accessed 1April 2016), and Wilson et al. (2013) scored it at the upper end of the medium vulnerability level. Data available on the life history and biology of A. ordinarium is restricted to the species description (Taylor, 1940), distribution (Shaffer, 1984; Anderson and Worthington, 1971), diet composition (Alvarado-Díaz et al., 2002), phylogeny (Weisrock et al., 2006) and the effect of habitat quality on diet diversity (Ruiz-Martínez et al., 2014). We did not find predation records on this species in the literature, and in this note we present information on a predation attack on an adult neotenic A. ordinarium by a Thamnophis cyrtopsis. On 13 July 2010 at 1300 h, while conducting an ecological study of A. -

Multi-National Conservation of Alligator Lizards

MULTI-NATIONAL CONSERVATION OF ALLIGATOR LIZARDS: APPLIED SOCIOECOLOGICAL LESSONS FROM A FLAGSHIP GROUP by ADAM G. CLAUSE (Under the Direction of John Maerz) ABSTRACT The Anthropocene is defined by unprecedented human influence on the biosphere. Integrative conservation recognizes this inextricable coupling of human and natural systems, and mobilizes multiple epistemologies to seek equitable, enduring solutions to complex socioecological issues. Although a central motivation of global conservation practice is to protect at-risk species, such organisms may be the subject of competing social perspectives that can impede robust interventions. Furthermore, imperiled species are often chronically understudied, which prevents the immediate application of data-driven quantitative modeling approaches in conservation decision making. Instead, real-world management goals are regularly prioritized on the basis of expert opinion. Here, I explore how an organismal natural history perspective, when grounded in a critique of established human judgements, can help resolve socioecological conflicts and contextualize perceived threats related to threatened species conservation and policy development. To achieve this, I leverage a multi-national system anchored by a diverse, enigmatic, and often endangered New World clade: alligator lizards. Using a threat analysis and status assessment, I show that one recent petition to list a California alligator lizard, Elgaria panamintina, under the US Endangered Species Act often contradicts the best available science. -

For Review Only

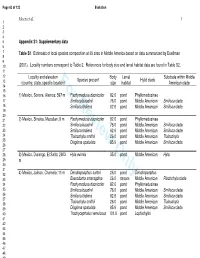

Page 63 of 123 Evolution Moen et al. 1 1 2 3 4 5 Appendix S1: Supplementary data 6 7 Table S1 . Estimates of local species composition at 39 sites in Middle America based on data summarized by Duellman 8 9 10 (2001). Locality numbers correspond to Table 2. References for body size and larval habitat data are found in Table S2. 11 12 Locality and elevation Body Larval Subclade within Middle Species present Hylid clade 13 (country, state, specific location)For Reviewsize Only habitat American clade 14 15 16 1) Mexico, Sonora, Alamos; 597 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 17 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 18 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 19 20 21 2) Mexico, Sinaloa, Mazatlan; 9 m Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 22 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 23 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 24 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 25 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 26 27 28 3) Mexico, Durango, El Salto; 2603 Hyla eximia 35.0 pond Middle American Hyla 29 m 30 31 32 4) Mexico, Jalisco, Chamela; 11 m Dendropsophus sartori 26.0 pond Dendropsophus 33 Exerodonta smaragdina 26.0 stream Middle American Plectrohyla clade 34 Pachymedusa dacnicolor 82.6 pond Phyllomedusinae 35 Smilisca baudinii 76.0 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 36 Smilisca fodiens 62.6 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 37 38 Tlalocohyla smithii 26.0 pond Middle American Tlalocohyla 39 Diaglena spatulata 85.9 pond Middle American Smilisca clade 40 Trachycephalus venulosus 101.0 pond Lophiohylini 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 52 53 54 55 56 57 58 59 60 Evolution Page 64 of 123 Moen et al. -

Pseudoeurycea Naucampatepetl. the Cofre De Perote Salamander Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico. This

Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl. The Cofre de Perote salamander is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This relatively large salamander (reported to attain a total length of 150 mm) is recorded only from, “a narrow ridge extending east from Cofre de Perote and terminating [on] a small peak (Cerro Volcancillo) at the type locality,” in central Veracruz, at elevations from 2,500 to 3,000 m (Amphibian Species of the World website). Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl has been assigned to the P. bellii complex of the P. bellii group (Raffaëlli 2007) and is considered most closely related to P. gigantea, a species endemic to the La specimens and has not been seen for 20 years, despite thorough surveys in 2003 and 2004 (EDGE; www.edgeofexistence.org), and thus it might be extinct. The habitat at the type locality (pine-oak forest with abundant bunch grass) lies within Lower Montane Wet Forest (Wilson and Johnson 2010; IUCN Red List website [accessed 21 April 2013]). The known specimens were “found beneath the surface of roadside banks” (www.edgeofexistence.org) along the road to Las Lajas Microwave Station, 15 kilometers (by road) south of Highway 140 from Las Vigas, Veracruz (Amphibian Species of the World website). This species is terrestrial and presumed to reproduce by direct development. Pseudoeurycea naucampatepetl is placed as number 89 in the top 100 Evolutionarily Distinct and Globally Endangered amphib- ians (EDGE; www.edgeofexistence.org). We calculated this animal’s EVS as 17, which is in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its IUCN status has been assessed as Critically Endangered. -

Crocodylus Moreletii

ANFIBIOS Y REPTILES: DIVERSIDAD E HISTORIA NATURAL VOLUMEN 03 NÚMERO 02 NOVIEMBRE 2020 ISSN: 2594-2158 Es un publicación de la CONSEJO DIRECTIVO 2019-2021 COMITÉ EDITORIAL Presidente Editor-en-Jefe Dr. Hibraim Adán Pérez Mendoza Dra. Leticia M. Ochoa Ochoa Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Senior Editors Vicepresidente Dr. Marcio Martins (Artigos em português) Dr. Óscar A. Flores Villela Dr. Sean M. Rovito (English papers) Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México Editores asociados Secretario Dr. Uri Omar García Vázquez Dra. Ana Bertha Gatica Colima Dr. Armando H. Escobedo-Galván Universidad Autónoma de Ciudad Juárez Dr. Oscar A. Flores Villela Dra. Irene Goyenechea Mayer Goyenechea Tesorero Dr. Rafael Lara Rezéndiz Dra. Anny Peralta García Dr. Norberto Martínez Méndez Conservación de Fauna del Noroeste Dra. Nancy R. Mejía Domínguez Dr. Jorge E. Morales Mavil Vocal Norte Dr. Hibraim A. Pérez Mendoza Dr. Juan Miguel Borja Jiménez Dr. Jacobo Reyes Velasco Universidad Juárez del Estado de Durango Dr. César A. Ríos Muñoz Dr. Marco A. Suárez Atilano Vocal Centro Dra. Ireri Suazo Ortuño M. en C. Ricardo Figueroa Huitrón Dr. Julián Velasco Vinasco Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México M. en C. Marco Antonio López Luna Dr. Adrián García Rodríguez Vocal Sur M. en C. Marco Antonio López Luna Universidad Juárez Autónoma de Tabasco English style corrector PhD candidate Brett Butler Diseño editorial Lic. Andrea Vargas Fernández M. en A. Rafael de Villa Magallón http://herpetologia.fciencias.unam.mx/index.php/revista NOTAS CIENTÍFICAS SKIN TEXTURE CHANGE IN DIASPORUS HYLAEFORMIS (ANURA: ELEUTHERODACTYLIDAE) ..................... 95 CONTENIDO Juan G. Abarca-Alvarado NOTES OF DIET IN HIGHLAND SNAKES RHADINAEA EDITORIAL CALLIGASTER AND RHADINELLA GODMANI (SQUAMATA:DIPSADIDAE) FROM COSTA RICA ..... -

The Niche, Biogeography and Species Interactions

Downloaded from rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org on July 18, 2011 The niche, biogeography and species interactions John J. Wiens Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 2011 366, 2336-2350 doi: 10.1098/rstb.2011.0059 References This article cites 85 articles, 14 of which can be accessed free http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/content/366/1576/2336.full.html#ref-list-1 Subject collections Articles on similar topics can be found in the following collections ecology (2529 articles) evolution (2816 articles) Receive free email alerts when new articles cite this article - sign up in the box at the top Email alerting service right-hand corner of the article or click here To subscribe to Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B go to: http://rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org/subscriptions This journal is © 2011 The Royal Society Downloaded from rstb.royalsocietypublishing.org on July 18, 2011 Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B (2011) 366, 2336–2350 doi:10.1098/rstb.2011.0059 Review The niche, biogeography and species interactions John J. Wiens* Department of Ecology and Evolution, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794-5245, USA In this paper, I review the relevance of the niche to biogeography, and what biogeography may tell us about the niche. The niche is defined as the combination of abiotic and biotic conditions where a species can persist. I argue that most biogeographic patterns are created by niche differences over space, and that even ‘geographic barriers’ must have an ecological basis. However, we know little about specific ecological factors underlying most biogeographic patterns. Some evidence supports the importance of abiotic factors, whereas few examples exist of large-scale patterns created by biotic interactions. -

BOA5.1-2 Frog Biology, Taxonomy and Biodiversity

The Biology of Amphibians Agnes Scott College Mark Mandica Executive Director The Amphibian Foundation [email protected] 678 379 TOAD (8623) Phyllomedusidae: Agalychnis annae 5.1-2: Frog Biology, Taxonomy & Biodiversity Part 2, Neobatrachia Hylidae: Dendropsophus ebraccatus CLassification of Order: Anura † Triadobatrachus Ascaphidae Leiopelmatidae Bombinatoridae Alytidae (Discoglossidae) Pipidae Rhynophrynidae Scaphiopopidae Pelodytidae Megophryidae Pelobatidae Heleophrynidae Nasikabatrachidae Sooglossidae Calyptocephalellidae Myobatrachidae Alsodidae Batrachylidae Bufonidae Ceratophryidae Cycloramphidae Hemiphractidae Hylodidae Leptodactylidae Odontophrynidae Rhinodermatidae Telmatobiidae Allophrynidae Centrolenidae Hylidae Dendrobatidae Brachycephalidae Ceuthomantidae Craugastoridae Eleutherodactylidae Strabomantidae Arthroleptidae Hyperoliidae Breviceptidae Hemisotidae Microhylidae Ceratobatrachidae Conrauidae Micrixalidae Nyctibatrachidae Petropedetidae Phrynobatrachidae Ptychadenidae Ranidae Ranixalidae Dicroglossidae Pyxicephalidae Rhacophoridae Mantellidae A B † 3 † † † Actinopterygian Coelacanth, Tetrapodomorpha †Amniota *Gerobatrachus (Ray-fin Fishes) Lungfish (stem-tetrapods) (Reptiles, Mammals)Lepospondyls † (’frogomander’) Eocaecilia GymnophionaKaraurus Caudata Triadobatrachus 2 Anura Sub Orders Super Families (including Apoda Urodela Prosalirus †) 1 Archaeobatrachia A Hyloidea 2 Mesobatrachia B Ranoidea 1 Anura Salientia 3 Neobatrachia Batrachia Lissamphibia *Gerobatrachus may be the sister taxon Salientia Temnospondyls -

Systematic Review of the Frog Family Hylidae, with Special Reference to Hylinae: Phylogenetic Analysis and Taxonomic Revision

SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE FROG FAMILY HYLIDAE, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO HYLINAE: PHYLOGENETIC ANALYSIS AND TAXONOMIC REVISION JULIAÂ N FAIVOVICH Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Herpetology), American Museum of Natural History Department of Ecology, Evolution, and Environmental Biology (E3B) Columbia University, New York, NY ([email protected]) CEÂ LIO F.B. HADDAD Departamento de Zoologia, Instituto de BiocieÃncias, Unversidade Estadual Paulista, C.P. 199 13506-900 Rio Claro, SaÄo Paulo, Brazil ([email protected]) PAULO C.A. GARCIA Universidade de Mogi das Cruzes, AÂ rea de CieÃncias da SauÂde Curso de Biologia, Rua CaÃndido Xavier de Almeida e Souza 200 08780-911 Mogi das Cruzes, SaÄo Paulo, Brazil and Museu de Zoologia, Universidade de SaÄo Paulo, SaÄo Paulo, Brazil ([email protected]) DARREL R. FROST Division of Vertebrate Zoology (Herpetology), American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) JONATHAN A. CAMPBELL Department of Biology, The University of Texas at Arlington Arlington, Texas 76019 ([email protected]) WARD C. WHEELER Division of Invertebrate Zoology, American Museum of Natural History ([email protected]) BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY CENTRAL PARK WEST AT 79TH STREET, NEW YORK, NY 10024 Number 294, 240 pp., 16 ®gures, 2 tables, 5 appendices Issued June 24, 2005 Copyright q American Museum of Natural History 2005 ISSN 0003-0090 CONTENTS Abstract ....................................................................... 6 Resumo ....................................................................... -

Phylogenetics, Classification, and Biogeography of the Treefrogs (Amphibia: Anura: Arboranae)

Zootaxa 4104 (1): 001–109 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Monograph ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4104.1.1 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:D598E724-C9E4-4BBA-B25D-511300A47B1D ZOOTAXA 4104 Phylogenetics, classification, and biogeography of the treefrogs (Amphibia: Anura: Arboranae) WILLIAM E. DUELLMAN1,3, ANGELA B. MARION2 & S. BLAIR HEDGES2 1Biodiversity Institute, University of Kansas, 1345 Jayhawk Blvd., Lawrence, Kansas 66045-7593, USA 2Center for Biodiversity, Temple University, 1925 N 12th Street, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19122-1601, USA 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Magnolia Press Auckland, New Zealand Accepted by M. Vences: 27 Oct. 2015; published: 19 Apr. 2016 WILLIAM E. DUELLMAN, ANGELA B. MARION & S. BLAIR HEDGES Phylogenetics, Classification, and Biogeography of the Treefrogs (Amphibia: Anura: Arboranae) (Zootaxa 4104) 109 pp.; 30 cm. 19 April 2016 ISBN 978-1-77557-937-3 (paperback) ISBN 978-1-77557-938-0 (Online edition) FIRST PUBLISHED IN 2016 BY Magnolia Press P.O. Box 41-383 Auckland 1346 New Zealand e-mail: [email protected] http://www.mapress.com/j/zt © 2016 Magnolia Press All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored, transmitted or disseminated, in any form, or by any means, without prior written permission from the publisher, to whom all requests to reproduce copyright material should be directed in writing. This authorization does not extend to any other kind of copying, by any means, in any form, and for any purpose other than private research use. -

Crotalus Tancitarensis. the Tancítaro Cross-Banded Mountain Rattlesnake

Crotalus tancitarensis. The Tancítaro cross-banded mountain rattlesnake is a small species (maximum recorded total length = 434 mm) known only from the upper elevations (3,220–3,225 m) of Cerro Tancítaro, the highest mountain in Michoacán, Mexico, where it inhabits pine-fir forest (Alvarado and Campbell 2004; Alvarado et al. 2007). Cerro Tancítaro lies in the western portion of the Transverse Volcanic Axis, which extends across Mexico from Jalisco to central Veracruz near the 20°N latitude. Its entire range is located within Parque Nacional Pico de Tancítaro (Campbell 2007), an area under threat from manmade fires, logging, avocado culture, and cattle raising. This attractive rattlesnake was described in 2004 by the senior author and Jonathan A. Campbell, and placed in the Crotalus intermedius group of Mexican montane rattlesnakes by Bryson et al. (2011). We calculated its EVS as 19, which is near the upper end of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), its IUCN status has been reported as Data Deficient (Campbell 2007), and this species is not listed by SEMARNAT. More information on the natural history and distribution of this species is available, however, which affects its conservation status (especially its IUCN status; Alvarado-Díaz et al. 2007). We consider C. tancitarensis one of the pre-eminent flagship reptile species for the state of Michoacán, and for Mexico in general. Photo by Javier Alvarado-Díaz. Amphib. Reptile Conserv. | http://amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 128 September 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e71 Copyright: © 2013 Alvarado-Díaz et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 128–170. -

Amphibians and Reptiles

Chapter 11 Amphibians and Reptiles Pierre Charruau, Jose´ Rogelio Cedeno-Va~ ´zquez, and Gunther Kohler€ Abstract The three Mexican states of the Yucata´n Peninsula have been relatively well explored for herpetofauna, when compared with other states of the country. However, most studies on the herpetofauna of the Yucata´n Peninsula have focused on their diversity, taxonomy, and species distribution, and less on their ecology, behavior or conservation status. The major conservation efforts have focused on sea turtles. Although some conservation programs exist locally for crocodiles in the north of the peninsula, to date conservation strategies have mostly been restricted to the designation of protected areas. With 24 species of amphibians and 118 species of reptiles, the Yucata´n Peninsula harbors 11.5 % of national herpetofauna diver- sity, and 19 % of species are endemic to the peninsula. Reptiles and amphibians are two major globally threatened groups of vertebrates, with amphibians being the most threatened vertebrate class. Both groups face the same threats, namely habitat loss and modification, pollution, overharvest for food and pet trade, introduction of exotic species, infectious diseases, and climatic change. Unfortunately, almost none of these issues have been investigated for key populations in the Yucata´n Peninsula. For amphibians, studies exploring the presence of the chytrid fungus (Batracho- chytrium dendrobatidis) and the effects of climatic change are badly needed to understand the specific factors that negatively affect populations in this area. In general, conservation efforts for reptiles and amphibians in the Yucata´n Peninsula need to include environmental education, scientific investigation, and law enforce- ment and application. -

Author's Personal Copy

Author's personal copy Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 55 (2010) 871–882 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev An expanded phylogeny of treefrogs (Hylidae) based on nuclear and mitochondrial sequence data John J. Wiens *, Caitlin A. Kuczynski, Xia Hua, Daniel S. Moen Department of Ecology and Evolution, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY 11794-5245, USA article info abstract Article history: The treefrogs (Hylidae) make up one of the most species-rich families of amphibians. With 885 species Received 3 August 2009 currently described, they contain >13% of all amphibian species. In recent years, there has been consid- Revised 11 February 2010 erable progress in resolving hylid phylogeny. However, the most comprehensive phylogeny to date Accepted 9 March 2010 (Wiens et al., 2006) included only 292 species, was based only on parsimony, provided only poor support Available online 19 March 2010 for most higher-level relationships, and conflicted with previous hypotheses in several parts (including the monophyly and relationships of major clades of Hylinae). Here, we present an expanded phylogeny Keywords: for hylid frogs, including data for 362 hylid taxa for up to 11 genes (4 mitochondrial, 7 nuclear), including Amphibians 70 additional taxa and >270 sequences not included in the previously most comprehensive analysis. The Anura Hylidae new tree from maximum likelihood analysis is more well-resolved, strongly supported, and concordant Mitochondrial DNA with previous hypotheses, and provides a framework for future systematic, biogeographic, ecological, and Nuclear DNA evolutionary studies. Phylogeny Ó 2010 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved. 1.