Participatory Research and CBCRM: in Context

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AGRIKULTURA CRI Journal 1 (1) ISSN: 2782-8816 January 2021 UTILIZATION and COMMERCIAL PRODUCTION of STINGLESS BEES and I

AGRIKULTURA CRI Journal 1 (1) ISSN: 2782-8816 January 2021 UTILIZATION AND COMMERCIAL PRODUCTION OF STINGLESS BEES AND ITS PRODUCTS IN BICOL, PHILIPPINES Maria Dulce J. Mostoles1*, Allan B. del Rosario1, Lilia C. Pasiona2, and Roberto R. Buenaagua3 1College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Central Bicol State University of Agriculture, Pili, Camarines Sur, 4418, Philippines 2College of Arts and Sciences, Central Bicol State University of Agriculture, Pili, Camarines Sur, 4418, Philippines 3Regional Apiculture Center , Central Bicol State University of Agriculture, Pili, Camarines Sur, 4418, Philippines *Corresponding author: [email protected] _________________________________________________________________ Abstract — Upscaling meliponiculture can increase income through the utilization and commercial production of the bee and its products. This includes improved and sustained production with the abundant colony and pollen sources, enhanced pollination, and developing health and wellness products from stingless bees. The research objectives were: map out the geographical distribution, abundance, and morphological characterization of stingless bees in the Bicol Region; determine the pollen sources of bees in meliponaries and bloom pattern in the area; determine the pollination efficiency by stingless bees on pigeon pea; and, develop food and cosmetic products from stingless bees. Stingless bee colonies were sighted in all provinces in Bicol. Geographical locations were: Albay (Daraga), Camarines Norte (San Lorenzo Ruiz), Camarines Sur (Goa, Iriga, Tinambac), Catanduanes (Viga, Bagamanoc, Panganiban), Masbate (Aroroy), Sorsogon (Bulusan, Casiguran, Pilar, Prieto Diaz) but most abundant in Albay. Open nested colonies with clustered brood are T. sapiens while closed nested colonies with spherical brood are T. biroi. Acetolyzed bee bread from different meliponaries confirmed the pollen sources and documented the plant species, raw pollen, acetolyzed pollen, and bloom pattern. -

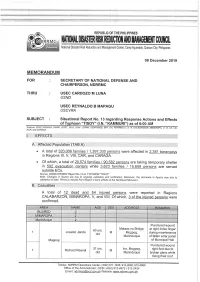

Response Actions and Effects of Typhoon "TISOY" (I.N

SitRep No. 13 TAB A Response Actions and Effects of Typhoon "TISOY" (I.N. KAMMURI) AFFECTED POPULATION As of 08 December 2019, 6:00 AM TOTAL SERVED Inside Evacuation Outside Evacuation (CURRENT) NO. OF AFFECTED REGION / PROVINCE / Centers Centers No. of ECs CITY / MUNICIPALITY (Inside + Outside) Brgys. Families Persons Families Persons Families Persons Families Persons GRAND TOTAL 2,381 320,006 1,397,330 592 20,574 90,582 3,623 15,659 24,197 106,241 REGION III 67 2,520 21,993 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Aurora 23 1,599 5,407 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Baler (Capital) 1 1 8 - - - - - - - Casiguran 5 784 2,496 - - - - - - - Dilasag 1 10 29 - - - - - - - Dinalungan 1 18 66 - - - - - - - Dingalan 10 761 2,666 - - - - - - - Dipaculao 1 16 93 - - - - - - - Maria Aurora 1 1 4 - - - - - - - San Luis 3 8 45 - - - - - - - Pampanga 6 153 416 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Arayat 1 17 82 - - - - - - Lubao 2 39 113 - - - - - - - Porac 2 90 200 - - - - - - - San Luis 1 7 21 - - - - - - - Bataan 25 699 3,085 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Abucay 2 51 158 - - - - - - - City of Balanga 1 7 25 - - - - - - - Dinalupihan 1 7 28 - - - - - - - Hermosa 1 20 70 - - - - - - - Limay 2 20 110 - - - - - - - Mariveles 5 278 1,159 - - - - - - - Orani 1 25 108 - - - - - - - Orion 9 260 1,305 - - - - - - - Pilar 3 31 122 - - - - - - - Bulacan 5 69 224 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Bulacan 2 16 48 - - - - - - - Obando 2 44 144 - - - - - - - Santa Maria 1 9 32 - - - - - - - Zambales 8 0 12,861 0 0 0 0 0 0 0 Botolan 3 - 10,611 - - - - - - - Iba 5 - 2,250 - - - - - - - REGION V 1,721 245,384 1,065,019 460 13,258 57,631 3,609 15,589 16,867 73,220 -

2018 Sorsogon Countryside in Figures

2018 COUNTRYSIDE IN FIGURES [Publish Date] FOREWORD Responding with the commitment to deliver relevant and disaggregated statistics at the local level, the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA), Sorsogon Provincial Office, Sorsogon is pleased to provide our stakeholders, constituents and clientele on our 2018 Countryside in Figures (CIF). This publication which contains relevant data and indicators about the performance of the province, and serve as a useful tool for researchers, students and local level planners. This 2018 edition is our first edition of Countryside in Figures (CIF) covers provincial data on the Overview, History, Topography, General Information, Population, Income and Expenditures, Agriculture, Health, Nutrition and Vital Statistics, Education, Fiscal Administration and Public Order & Safety of the province. Some municipal level data were also presented. We look forward that this publication will be enhanced more in the years to come up with a more comprehensive statistics in order to cater to the needs for useful planning and decision making towards evidenced-based local governance and increase the appreciation on the importance of statistics in the grassroots. ELVIRA O. APOGNOL Chief Statistical Specialist PHILIPPINE STATISTICS AUTHORITY – SORSOGON PROVINCIAL STATISTICS OFFICE 1 2018 COUNTRYSIDE IN FIGURES [Publish Date] Philippine Statistics Authority Provincial Statistics Office Sorsogon LIST OF PERSONNEL Elvira O. Apognol Gemma L. Red Ma. Donna E. Guemo Razel M. Gomez Ines N. Heta Anselma E. Bonto Gaudencio B. -

A Political Economy Analysis of the Bicol Region

fi ABC+: Advancing Basic Education in the Philippines A POLITICAL ECONOMY ANALYSIS OF THE BICOL REGION Final Report Ateneo Social Science Research Center September 30, 2020 ABC+ Advancing Basic Education in the Philippines A Political Economy Analysis of the Bicol Region Ateneo Social Science Research Center Final Report | September 30, 2020 Published by: Ateneo de Naga University - Ateneo Social Science Research Center Author/ Project lead: Marlyn Lee-Tejada Co-author: Frances Michelle C. Nubla Research Associate: Mary Grace Joyce Alis-Besenio Research Assistants: Jesabe S.J. Agor and Jenly P. Balaquiao The authors’ views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect the views of the United States Agency for International Development or the United States Government, the Department of Education, the RTI International, and The Asia Foundation. Table of Contents ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................... v EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ............................................................................................................ 1 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................ 5 Methodology .................................................................................................................... 6 Sampling Design .............................................................................................................. 6 Data Collection -

31 October 2020

31 October 2020 At 5:00 AM, TY "ROLLY" maintains its strength as it moves closer towards Bicol Region. The eye of Typhoon "ROLLY" was located based on all available data at 655 km East Northeast of Virac, Catanduanes. TCWS No. 2 was raised over Catanduanes, the eastern portion of Camarines Sur, Albay, and Sorsogon. While TCWS No.1 was raised over Camarines Norte, the rest of Camarines Sur, Masbate including Ticao and Burias Islands, Quezon including Polillo Islands, Rizal, Laguna, Cavite, Batangas, Marinduque, Romblon, Occidental Mindoro including Lubang Island, Oriental Mindoro, Metro Manila, Bulacan, Pampanga, Bataan, Zambales, Tarlac, Nueva Ecija, Aurora, Pangasinan, Benguet, Ifugao, Nueva Vizcaya, Quirino, and the southern portion of Isabela, Northern Samar, the northern portion of Samar, the northern portion of Eastern Samar, and the northern portion of Biliran. At 7:00 PM, the eye of TY "ROLLY" was located based on all available data at 280 km East Northeast of Virac, Catanduanes. "ROLLY" maintains its strength as it threatens Bicol Region. The center of the eye of the typhoon is likely to make landfall over Catanduanes early morning of 01 November 2020, then it will pass over mainland Camarines Provinces tomorrow morning, and over mainland Quezon tomorrow afternoon. At 10:00 PM, the eye of TY "ROLLY" was located based on all available data including those from Virac and Daet Doppler Weather Radars at 185 km East of Virac, Catanduanes. Bicol Region is now under serious threat as TY "ROLLY" continues to move closer towards Catanduanes. Violent winds and intense to torrential rainfall associated with the inner rainband-eyewall region will be experienced over (1) Catanduanes tonight through morning; (2) Camarines Provinces and the northern portion of Albay including Rapu-Rapu Islands tomorrow early morning through afternoon. -

Pres. Duterte Allocates P500 Million for Typhoon Nina Rehab in Bicol

October - December 2016 Vol. 25 No. 4 President Rodrigo LGU Sorsogon Duterte meets the local chief executives and selected wins P1million as farmers of Camarines Sur “Be Riceponsible” at the Provincial Capitol in Cadlan, Pili, Camarines Sur, advocacy champion three days after typhoon Nina ravaged Bicol. Photo The provincial government shows President Duterte of Sorsogon, Bicol’s lone entry consulting agriculture to the DA-Philippine Rice secretary Manny F. Piñol on Research Institute (PhilRice) DA’s rehabilitation funds. nationwide BeRiceponsible Search for Best Advocacy Campaign was adjudged as champion under the Provincial Government category and won P1 Million cash prize. Hazel V. Antonio, director Pres. Duterte allocates P500 million of the Be RICEponsible campaign led the awarding ceremony which was held at for typhoon Nina rehab in Bicol PhilRice in Nueva Ecija on by Emily B. Bordado (Please turn to page 15) Typhoon Nina devastated three Bicol provinces and wrought heavy damage on the agriculture sector. FULL FLEDGED. Final damage report shows that the number of Agriculture farmers affected from the province of Camarines Sur, Secretary Catanduanes and Albay is 86,735. Of this, 73,757 are rice Emmanuel farmers; 8,387 corn farmers and 4,002 are high value F. Piñol crop farmers. The value of production loss is estimated administered at over P5.1 billion. the oath of office to The total rice area affected planting anew. The assistance our beloved is 59,528.23 hectare; for corn will be in the form of palay Regional 12,727.17 hectare and for seeds to be distributed to the Executive high value crops including affected farmers. -

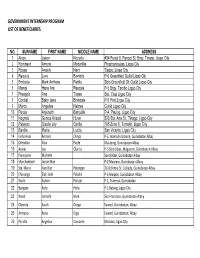

Government Internship Program List of Beneficiaries

GOVERNMENT INTERNSHIP PROGRAM LIST OF BENEFICIARIES NO. SURNAME FIRST NAME MIDDLE NAME ADDRESS 1 Alcoy Jason Nocedo #34 Purok 8, Pangol St. Brgy. Tinago, Ligao City 2 Rombaon Amyrie Medenilla Pinamaniquian, Ligao City 3 Rosas Angely Nario Tagpo, Ligao City 4 Requiza Juvy Bombita P-6 Greenfield Guilid Ligao City 5 Embudo Mark Anthony Perillo Sitio Greenfield St. Guilid Ligao City 6 Manga Hana Ara Rescate P-5 Brgy. Tambo Ligao City 7 Preagola Ana Topasi Sta. Cruz Ligao City 8 Cordial Baby Jane Broncate P-5 Pinit Ligao City 9 Morco Angeline Nebres Guilid Ligao City 10 Persia Anjeneth Barquilla P-4, Paulog, Ligao City 11 Negrete Genica Krissel Hizon 523 Sta. Ana St., Tinago, Ligao City 12 Patanao Giselle Joy Carilla 165 Zone 6, Tomolin, Ligao City 13 Banilla Ronie Locito San Vicente, Ligao City 14 Llenaresas Bernard Olayta P-5, Inamnan Grande, Guinobatan Albay 15 Orendain Aiza Payte Malabing, Guinobatan Albay 16 Azares Joy Olarita P-3 Sitio Libas, Maguiron, Guinobatan Albay 17 Pancipane Michelle San Rafael, Guinobatan Albay 18 Marchadesch Joysie Mae P-2 Mauraro, Guinobatan Albay 19 Sta. Maria Ivan Rae Patangan 36 Ocfemia St. Calzada, Guinobatan Albay 20 Ehurango Elah Jade Paladin P-6 Maipon, Guinobatan Albay 21 Nocle Aljhon Porlaje P-1, Travesia, Guinobatan 22 Bangate Niño Peña P-1 Batang, Ligao City 23 Nasol Jonnafe Nate San Francisco, Guinobatan Albay 24 Obenita Sarah Orogo Ilawod, Guinobatan, Albay 25 Armario Rena Diga Ilawod, Guinobatan, Albay 26 Peralta Angelica Cascante Mahaba, Ligao City 27 Monasterial Vergel Kim Tranquilino Calzada, Ligao City 28 Ramos Josefina Botalon Basag, Ligao City 29 Bicol Gabrielle Michel Sayson San Miguel St. -

![Solid Waste Management Sector Project (Financed by ADB's Technical Assistance Special Fund [TASF- Other Sources])](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9882/solid-waste-management-sector-project-financed-by-adbs-technical-assistance-special-fund-tasf-other-sources-3729882.webp)

Solid Waste Management Sector Project (Financed by ADB's Technical Assistance Special Fund [TASF- Other Sources])

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: 45146 December 2014 Republic of the Philippines: Solid Waste Management Sector Project (Financed by ADB's Technical Assistance Special Fund [TASF- other sources]) Prepared by SEURECA and PHILKOEI International, Inc., in association with Lahmeyer IDP Consult For the Department of Environment and Natural Resources and Asian Development Bank This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR PROJECT TA-8115 PHI Final Report December 2014 In association with THE PHILIPPINES THE PHILIPPINES DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENT AND NATURAL RESOURCES ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK SOLID WASTE MANAGEMENT SECTOR PROJECT TA-8115 PHHI SR10a Del Carmen SR12: Poverty and Social SRs to RRP from 1 to 9 SPAR Dimensions & Resettlement and IP Frameworks SR1: SR10b Janiuay SPA External Assistance to PART I: Poverty, Social Philippines Development and Gender SR2: Summary of SR10c La Trinidad PART II: Involuntary Resettlement Description of Subprojects SPAR and IPs SR3: Project Implementation SR10d Malay/ Boracay SR13 Institutional Development Final and Management Structure SPAR and Private Sector Participation Report SR4: Implementation R11a Del Carmen IEE SR14 Workshops and Field Reports Schedule and REA SR5: Capacity Development SR11b Janiuay IEEE and Plan REA SR6: Financial Management SR11c La Trinidad IEE Assessment and REAE SR7: Procurement Capacity SR11d Malay/ Boracay PAM Assessment IEE and REA SR8: Consultation and Participation Plan RRP SR9: Poverty and Social Dimensions December 2014 In association with THE PHILIPPINES EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ....................................................................................5 A. -

Summary of Barangays Susceptible to Bulusan

Republic of the Philippines DEPARTMENT OF SCIENCE AND TECHNOLOGY PHILIPPINE INSTITUTE OF VOLCANOLOGY AND SEISMOLOGY SUMMARY OF BARANGAYS SUSCEPTIBLE TO BULUSAN LAHARS MUNICIPALITY BARANGAY HIGH MODERATE LOW SAFE RIVER CHANNEL BARCELONA Alegria N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona BARCELONA Bagacay N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona BARCELONA Bangate N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Calagoto BARCELONA Bugtong N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona BARCELONA Cagang - - - YES BARCELONA Fabrica N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Layog, Tagdon BARCELONA Jibong N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Tagdon BARCELONA Lago N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona BARCELONA Layog N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Layog BARCELONA Luneta N N PARTLY PARTLY Tagdon BARCELONA Macabari N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Bangati, Bon-ot BARCELONA Mapapac N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Tagdon BARCELONA Olandia N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Tagdon BARCELONA Paghaluban N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Layog BARCELONA Poblacion Central N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona BARCELONA Poblacion Norte N PARTLY PARTLY - Barcelona BARCELONA Poblacion Sur - - - YES BARCELONA Putiao N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Layog BARCELONA San Antonio N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Tagdon BARCELONA San Isidro N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona BARCELONA San Ramon N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Calagoto, Layog BARCELONA San Vicente N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY BArcelona BARCELONA Santa Cruz N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Calagoto, Bon-ot, Layog BARCELONA Santa Lourdes N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Barcelona, Tagdon BARCELONA Tagdon N PARTLY PARTLY PARTLY Tagdon BULAN A. Bonifacio - - - YES BULAN Abad Santos - - - YES BULAN Aguinaldo - - - YES BULAN Antipolo - - - YES BULAN Beguin - - - YES BULAN Benigno S. Aquino (Imelda) - - - YES BULAN Bical - - - YES BULAN Bonga - - - YES BULAN Butag - - - YES BULAN Cadandanan - - - YES BULAN Calomagon - - - YES BULAN Calpi - - - YES BULAN Cocok-Cabitan - - - YES BULAN Daganas - - - YES BULAN Danao - - - YES BULAN Dolos - - - YES BULAN E. -

Backgrounder on the Rapu Rapu Mining Operation

Mineral Institute Backgrounder: Rapu Rapu Mining Operation: July 2006 Backgrounder on the Rapu Rapu Mining Operation Executive Summary: The Rapu Rapu Mining Project, majority owned and operated by Australian mining company, Lafayette has been mired in controversy since its conception, and opposed by a variety of local and national actors in the Philippines. This paper seeks to outline the major points of concern in relation to this project. The following issues relating to the projects have been investigated and evaluated by various Philippines government initiatives and are discussed in this paper with reference to the relevant supporting government reports: 1. Inadequacy of Environmental and Social Impact Assessment Process: 2. Serious toxic spills and related findings of negligence and breaches of basic industry practices 3. Unresolved Community Impacts and Questionable Social Acceptability: -Exclusion of impacted groups from consultation process: -Widespread opposition to the mine across the island: -Failure to respect rights of Indigenous People: -Serious impacts on and risks to sustainable livelihoods: 4. Ongoing Inadequacies in Rapu Rapu’s operations: -Acid Rock Drainage: -Toxic Discharges: -Tailings Dam Design: -Inadequate monitoring by the state: 5. Illegitimate Corporate Structures: 6. Undue Pressure by the company on government structures: 7. Taxes: Underreporting of Production and Possible Tax Cheating The gross and serious violations of laws, regulations and basic industry practice across the full spectrum of social, environmental -

San Bernardino Strait - Ticao Pass Fisheries Management Area

ECOSYSTEM-APPROACH TO FISHERIES MANAGEMENT (EAFM) SAN BERNARDINO STRAIT - TICAO PASS FISHERIES MANAGEMENT AREA EAFM PLAN (2017- 2022) 1 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION 3 I. VISION 7 II. SITE BACKGROUND 8 Biophysical & Socio-economic Setting 8 Fisheries Status 9 Management Status 12 III. MAJOR ISSUES AND PROBLEMS 13 IV. GOALS 15 Conflict Map 16 V. OBJECTIVES, INDICATORS AND BENCHMARKS 17 GOAL 1 18 GOAL 2 19 GOAL 3 19 GOAL 4 19 VI. Management Actions 21 GOAL 1 21 GOAL 2 24 GOAL 3 26 GOAL 4 30 VII. Sustainable Financing 35 VIII. Implementation Plan and Communication Strategy 36 IX. Validation and Adoption of the EAFM Plan 38 2 INTRODUCTION This Ecosystem Approach to Fisheries Management 1. Workshop 1 – Overview and Start-up Tasks – (EAFM) Plan presents the vision, goals, objectives and October 2016, Tacloban City, Tacloban. integrated set of management actions for the San Ber- 2. Workshop 2- Development of the draft EAFM nardino Strait-Ticao Pass (SBS-TP) fisheries manage- Plan – January 30 – February 3, 2017, Calbayog, ment area (FMA) for the period 2017-2022. The EAFM Northern Samar; validated on April 26, 2017, is a holistic approach to fisheries management that Sorsogon City. involves systems and decision-making processes that 3. Stakeholder Consultation – Validation and balance ecological well-being with human and societal adoption of the EAFM Plan - by each LGU well-being, within improved governance frameworks. The key stakeholders have given full commitment to im- The plan is a product of a highly participatory process plement this EAFM Plan in their FMA. The participating that involved key stakeholders from Allen, San Antonio, LGUs will be implementers of local government actions Lavezares, Capul, Biri, San Vicente, Prieto Diaz, Gubat, within their political jurisdictions, and as partners in the Barcelona, Bulusan, Sta. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population ALBAY

2010 Census of Population and Housing Albay Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population ALBAY 1,233,432 BACACAY 65,724 Baclayon 2,397 Banao 1,379 Bariw 601 Basud 1,523 Bayandong 1,615 Bonga (Upper) 7,468 Buang 1,267 Cabasan 2,004 Cagbulacao 842 Cagraray 767 Cajogutan 1,090 Cawayan 1,116 Damacan 466 Gubat Ilawod 1,043 Gubat Iraya 1,138 Hindi 3,458 Igang 2,128 Langaton 757 Manaet 764 Mapulang Daga 529 Mataas 478 Misibis 934 Nahapunan 406 Namanday 1,440 Namantao 901 Napao 1,690 Panarayon 1,658 Pigcobohan 838 Pili Ilawod 1,284 Pili Iraya 924 Barangay 1 (Pob.) 1,078 Barangay 10 (Pob.) 652 Barangay 11 (Pob.) 194 Barangay 12 (Pob.) 305 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Albay Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Barangay 13 (Pob.) 1,249 Barangay 14 (Pob.) 1,176 Barangay 2 (Pob.) 282 Barangay 3 (Pob.) 543 Barangay 4 (Pob.) 277 Barangay 5 (Pob.) 279 Barangay 6 (Pob.) 266 Barangay 7 (Pob.) 262 Barangay 8 (Pob.) 122 Barangay 9 (Pob.) 631 Pongco (Lower Bonga) 960 Busdac (San Jose) 1,082 San Pablo 1,240 San Pedro 1,516 Sogod 4,433 Sula 960 Tambilagao (Tambognon) 920 Tambongon (Tambilagao) 748 Tanagan 1,486 Uson 625 Vinisitahan-Basud (Mainland) 607 Vinisitahan-Napao (lsland) 926 CAMALIG 63,585 Anoling 968 Baligang a 3,286 Bantonan 596 Bariw 1,870 Binanderahan 554 Binitayan 564 Bongabong 917 Cabagñan 2,682 Cabraran Pequeño