Bardney Abbey 1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

First Evidence of Farming Appears; Stone Axes, Antler Combs, Pottery in Common Use

BC c.5000 - Neolithic (new stone age) Period begins; first evidence of farming appears; stone axes, antler combs, pottery in common use. c.4000 - Construction of the "Sweet Track" (named for its discoverer, Ray Sweet) begun; many similar raised, wooden walkways were constructed at this time providing a way to traverse the low, boggy, swampy areas in the Somerset Levels, near Glastonbury; earliest-known camps or communities appear (ie. Hembury, Devon). c.3500-3000 - First appearance of long barrows and chambered tombs; at Hambledon Hill (Dorset), the primitive burial rite known as "corpse exposure" was practiced, wherein bodies were left in the open air to decompose or be consumed by animals and birds. c.3000-2500 - Castlerigg Stone Circle (Cumbria), one of Britain's earliest and most beautiful, begun; Pentre Ifan (Dyfed), a classic example of a chambered tomb, constructed; Bryn Celli Ddu (Anglesey), known as the "mound in the dark grove," begun, one of the finest examples of a "passage grave." c.2500 - Bronze Age begins; multi-chambered tombs in use (ie. West Kennet Long Barrow) first appearance of henge "monuments;" construction begun on Silbury Hill, Europe's largest prehistoric, man-made hill (132 ft); "Beaker Folk," identified by the pottery beakers (along with other objects) found in their single burial sites. c.2500-1500 - Most stone circles in British Isles erected during this period; pupose of the circles is uncertain, although most experts speculate that they had either astronomical or ritual uses. c.2300 - Construction begun on Britain's largest stone circle at Avebury. c.2000 - Metal objects are widely manufactured in England about this time, first from copper, then with arsenic and tin added; woven cloth appears in Britain, evidenced by findings of pins and cloth fasteners in graves; construction begun on Stonehenge's inner ring of bluestones. -

Lincoln Board of Education the Church of England

DIOCESE OF LINCOLN BOARD OF EDUCATION THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND DIOCESE OF LINCOLN BOARD OF EDUCATION THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND Diocesan Service Level Agreement and Professional Development Programme AcAdemic yeAr 2019-2020 DIOCESE OF LINCOLN BOARD OF EDUCATION THE CHURCH OF ENGLAND 2 From the Diocesan director of education Dear Colleagues, I am delighted to be able to offer you the 2019/20 SLA and course programme. You will see that we have further developed the offer. As ever we have taken into account all that you have fed back to us. I’m particularly keen to point out the new Governors’ Network Meetings (see diary of events page 14) which are free to all schools in the SLA. I think that they will really help governors to become confident in their complex roles and share best practice - you can send along as many governors as you want! Our support for RE, SIAMS, collective worship and leadership obviously continues to grow but our emphasis this year is on well-being and mental health. I’m delighted that our Education Development Officer Lynsey Norris is a qualified Mental Health First Aid Instructor running three courses this year to train members of your team to be Mental Health First Aiders (see page 16). The Diocesan Education Team also continues to offer Bespoke and Off the Peg sessions (see page 12), training delivered by our officers to one school or a cluster at a mutually agreed time and place. The team continues to strive to meet your needs so that you can meet the needs of the 28,000 pupils in your care, providing an education of Excellence, Exploration and Encouragement within the love of God. -

Our Resource Is the Gospel, and Our Aim Is Simple;

Bolingbroke Deanery GGr raappeeVViinnee MAY 2016 ISSUE 479 • Mission Statement The Diocese of Lincoln is called by God to faithful worship, confident discipleship and joyful service. • Vision Statement To be a healthy, vibrant and sustainable church, transforming lives in Greater Lincolnshire 50p 1 Bishop’s Letter Dear Friends, Many of us will have experienced moments of awful isolation in our lives, or of panic, or of sheer joy. The range of situations, and of emotions, to which we can be exposed is huge. These things help to form the richness of human living. But in themselves they can sometimes be immensely difficult to handle. Jesus’ promise was to be with his friends. Although they experienced the crushing sadness of his death, and the huge sense of betrayal that most of them felt in terms of their own abandonment of him, they also experienced the joy of his resurrection and the happiness of new times spent with him. They would naturally have understood that his promise to ‘be with them’ meant that he would not physically leave them. However, what Jesus meant when he said that they would not be left on their own was that the Holy Spirit would always be with them. It is the Spirit, the third Person of the Holy Trinity, that we celebrate during the month of May. Jesus is taken from us, body and all, but the Holy Spirit is poured out for us and on to us. The Feast of the Holy Spirit is Pentecost. It happens at the end of Eastertide, and thus marks the very last transition that began weeks before when, on Ash Wednesday, we entered the wilderness in preparation for Holy Week and Eastertide to come. -

GS Misc 1095 GENERAL SYNOD the Dioceses Commission Annual

GS Misc 1095 GENERAL SYNOD The Dioceses Commission Annual Report 2014 1. The Dioceses Commission is required to report annually to the General Synod. This is its seventh report. 2. It consists of a Chair and Vice-Chair appointed by the Archbishops of Canterbury and York from among the members of the General Synod; four members elected by the Synod; and four members appointed by the Appointments Committee. Membership and Staff 3. The membership and staff of the Commission are as follows: Chair: Canon Prof. Michael Clarke (Worcester) Vice-Chair: The Ven Peter Hill (to July 2014) The Revd P Benfield (from November 2014) Elected Members: The Revd Canon Jonathan Alderton-Ford (St Eds & Ips) The Revd Paul Benfield (Blackburn) (to November 2014) Mr Robert Hammond (Chelmsford) Mr Keith Malcouronne (Guildford) Vacancy from November 2014 Appointed Members: The Rt Revd Christopher Foster, Bishop of Portsmouth (from March 2014) Mrs Lucinda Herklots The Revd Canon Dame Sarah Mullally, DBE Canon Prof. Hilary Russell Secretary: Mr Jonathan Neil-Smith Assistant Secretary: Mr Paul Clarkson (to March 2014) Mrs Diane Griffiths (from April 2014) 4. The Ven Peter Hill stepped down as Vice-Chair of the Commission upon his appointment as Bishop of Barking in July 2014. The Commission wishes to place on record their gratitude to Bishop Peter for his contribution as Vice-Chair to the Commission over the last three years. The Revd Paul Benfield was appointed by the Archbishops as the new Vice-Chair of the Commission in November 2014. 5. Mrs Diane Griffiths succeeded Paul Clarkson as Assistant Secretary to the Commission. -

Lincolnshire. Pob 833

TRADES DIRECTORY.] LINCOLNSHIRE. POB 833 PICTURE DEALER. I Batson Edwin, Uleeby Village Payue John Nicholson, Coningsby, Bostoa. Moore Lemuel Watson, 119 Victoria street Bean William, Church street, Hollx>ach Payne ThomM, Navenby, Grantham Bee Henry, 16 Upgate, Louth Payne ThomM, Swineshead, Spalding south, Great Grimsby Beeby Charles, Sutterton, Spalding Pilkington John, 4 Langworthgate, Lincoln PICTURE FRAME MAKERS. Bell John, Moulton, Spalding Pilkington Thomas, Eastgate, Lincoln . Bo<'ock Robert, 25 Strait, Lincoln Pindard James, 7 Church street, Boston Baildom. J_arnes, 129 Eastgate, Louth Boole George, 368 High street, Lincoln Plowright Jspb. Stamford ru.Market Deeping Bean Williarn, Church street, Holbeaeh. Brierley Henry, Eastgate, Sleaford Plumtree .John, North Thoresby, Louth Bennett. Sarnl.lO & 20FrePman. st.Gt.G!'lmsby Bromitt William, Tydd St. Mary, Wisbech Priestley Frederick, Wragby Brum~mt Hy. n:. & Co. 243 High st. Lmcoln Brooks Thomas, Moulton, Spalding Pulford James,High st. Long Sutton.Wisbch Cheshire Zachanah, 9 Worm gate, Boston Brown & Buxton, 7 & 9 Bridge st. Horncastle Reeve William, 37 Melville street, Lincoln Clarke William, Market pl. Crowle,Doncaster Brown Jas. Dixon, 39 Pasture st. Gt.Grimsby Rimington Fredk. Wm. Ashby road, Spilsby Fisher Robert, 1 Steep hill, Lincoln Brown William F. H og8thorpe, .AJford Rimington Thomas Ed\\in, North Somer- Fox Thomas, 78 Brirlge street, Gainsborougli Brummitt John, Sutton Bridge, Wisbech cotes, Great Grimsby Lawrence George, 45 Sincil street, Lincoln Burton Joseph, Winterton, Doncaster Ripdon Thomas, 19 Swinegate, Grantho.m Lenton Edgar James, Kirton Lindsey R.S.O Bywater Robert, 115 Eastgate, Lonth Robinson & Emerson, 222 Victoria street Le"is George, M Church st. Great Grimsby Cargill Thos. -

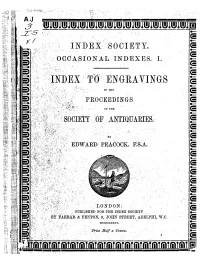

Index to Engravings in the Proceedings of the Society Of

/ r / INDEX SOCIETY. E> OCCASIONAL INDEXES. I. INDEX TO ENGRAVINGS IN THE I PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY OF ANTIQUARIES. BY EDWARD PEACOCK, F.S.A. V -Λ\’ LONDON: PUBLISHED FOR THE INDEX SOCIETY BY FARRAR & FENTON, 8, JOHN STREET, ADELPHI, W.C. ■·.··* ' i: - ··. \ MDCCCLXXXV. ' Price Half a Crown. 2730130227001326270013022700440227004426 INDEX SOCIETY. T he Council greatly regret that owing to various circum stances the publications have fallen very much behindhand in the order of their publication, but they trust that in the future the Members will have no reason to complain on this score. The Index of Obituary Notices for 1882 is ready and will be in the Members’ hands immediately. The Index for 1883 is nearly ready, and this with the Index to Archaeological Journals and Transactions, upon which Mr. Gomme has been engaged for some time, will complete the publications for 1884. The Index of the Biographical and Obituary Notices in the Gentleman’s Magazine for the first fifty years, upon which Mr. Farrar is engaged, has occupied an amount of time in revision considerably greater than was expected. This is largely owing to the great differences in the various sets, no two being alike. No one who has not been in the habit of consulting the early volumes of this Magazine con stantly can have any idea of the careless manner in which it was printed and the vast amount of irregularity in the pagination. Mr. Farrar has spared no pains in the revision of these points and the Council confidently expect to be able to present Members with the first volume of this im portant work in the course of the present year (1885). -

POST OFFICE LINCOLNSHIRE • Butche Rt;-Continued

340 POST OFFICE LINCOLNSHIRE • BuTCHE Rt;-continued. Evison J. W alkergate, Louth Hare R. Broughton, Bri~g · Cocks P. Hawthorpe, Irnham, Bourn Farbon L. East street, Horncastle Hare T. Billingborough, Falkingbam Codd J. H. 29 Waterside north, Lincoln Featherstone C. S. Market place, Bourn Hare T. Scredington, Falkingham Coldren H. Manthorpe rood, Little Featherstone J. All Sai,nts' street & High Hare W. Billingborough, Falkingharn Gonerby, Grantham street, Stamford Harmstone J. Abbey yard, Spalding tf Cole J • .Baston, Market Deeping Feneley G. Dorrington, Sleaford Harr G. All Saints street, Stamford Cole W. Eastgate, Louth Firth C. Bull street, Homcastle Harrison B. Quadring, Spalding Collingham G. North Scarle, N ewark Fish .J. West l"erry, Owston Harrison C. Scopwick, Sleaford · Connington E. High street, Stamford Fisher C. Oxford street, Market Rasen Harrison G. Brant Broughton, Newark Cook J. Wootton, Ulceby Fisher H. Westg11te, New Sleaford Harrison H. Bardney, Wragby Cooper B. Broad street, Grantham Fisher J. Tealby, Market Rasen Harrison R. East Butterwick, Bawtry f Cooper G. Kirton-in-Lindsey Folley R. K. Long Sutton Harrison T. We1ton, Lincoln Cooper J. Swaton, Falkingham Forman E. Helpringham, Sleaford Harrison W. Bridge st. Gainsborougb Cooper L • .Barrow-on-Humber, Ulceby Foster E. Caistor HarrisonW.Carlton-le-Moorland,Newrk Cooper M. Ulceby Foster Mrs. E. Epworth Harrod J, jun. Hogsthorpe, Alford Cooper R. Holbeach bank, Holbeach Foster J. Alkborough, Brigg Harvey J. Old Sleaford Coopland H. M. Old Market lane, Bar- Foster W. Chapel street, Little Gonerby, Harvey J. jun. Bridge st. New Sleaford ton-on~Humbm• Grantham Hastings J. Morton-by-Gainsborough CooplandJ.Barrow-on-Humber,Ulceby Foster W. -

Unlocking New Opportunies

A 37 ACRE COMMERCIAL PARK ON THE A17 WITH 485,000 SQ FT OF FLEXIBLE BUSINESS UNITS UNLOCKING NEW OPPORTUNIES IN NORTH KESTEVEN SLEAFORD MOOR ENTERPRISE PARK IS A NEW STRATEGIC SITE CONNECTIVITY The site is adjacent to the A17, a strategic east It’s in walking distance of local amenities in EMPLOYMENT SITE IN SLEAFORD, THE HEART OF LINCOLNSHIRE. west road link across Lincolnshire connecting the Sleaford and access to green space including A1 with east coast ports. The road’s infrastructure the bordering woodlands. close to the site is currently undergoing The park will offer high quality units in an attractive improvements ahead of jobs and housing growth. The site will also benefit from a substantial landscaping scheme as part of the Council’s landscaped setting to serve the needs of growing businesses The site is an extension to the already aims to ensure a green environment and established industrial area in the north east resilient tree population in NK. and unlock further economic and employment growth. of Sleaford, creating potential for local supply chains, innovation and collaboration. A17 A17 WHY WORK IN NORTH KESTEVEN? LOW CRIME RATE SKILLED WORKFORCE LOW COST BASE RATE HUBS IN SLEAFORD AND NORTH HYKEHAM SPACE AVAILABLE Infrastructure work is Bespoke units can be provided on a design and programmed to complete build basis, subject to terms and conditions. in 2021 followed by phased Consideration will be given to freehold sale of SEE MORE OF THE individual plots or constructed units, including development of units, made turnkey solutions. SITE BY SCANNING available for leasehold and All units will be built with both sustainability and The site is well located with strong, frontage visibility THE QR CODE HERE ranging in size and use adaptability in mind, minimising running costs from the A17, giving easy access to the A46 and A1 (B1, B2 and B8 use classes). -

Inhouse Autumn 2016

Issue 34: Autumn edition 2016 InHousethe Journal of the Lincoln Cathedral Community Association Rome The Bishop’s Eye remembered Page 9 Page 5 Messy Cathedral Elaine Johnson Messy Cathedral on the 26th July was a celebration of the many Messy Churches to be found now in so many of the Diocese of Lincoln’s churches. It was a taster for the notion of Messy Church and also opened the cathedral building to families in an informal and welcoming way. Messy Church is established world- wide. It is a fun way of being church for families, with its values being Christ-cen- tred, for all ages, based on creativity, hospitality and celebration. Philippa, who led the event in the Cathedral, al- ready runs a successful Messy Church at St John the Baptist in Lincoln and ran Messy Cathedral for the first time last year, with almost one hundred people taking part. This time attendance dou- bled. Nearly two hundred participants heard stories and did craft activities based on the parables of the Sower, the Lost Sheep, the Good Samaritan and the Prodigal Son. The session then moved into a ‘celebration’ time of more formal worship before finishing with everyone having a picnic lunch together. For many families, Messy Church is their church, where they first encoun- ter Christ and which they start to attend regularly. Many Messy Churches receive requests for baptism and confirmation. in touch with their local parish church Not all those people want to make a and the Messy Church in their area and transition into ‘traditional’ church, but several said they would. -

Christopher Michael Woolgar: "The Development of Accounts for Private Households in England to C,1500 A.D."

Christopher Michael Woolgar: "The development of accounts for private households in England to c,1500 A.D." A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of Durham, 1986 Abstract The first written accounts for private households in England date from the late twelfth century. They probably derive from a system of accounting based on an oral report, supported by a minimum of documentation, and they were closely associated with a broad change in the method of provisioning households from a dependence on food farms to a network of supply based on purchase. The earliest private household accounts are daily or "diet" accounts, recording purchases alone. From the earliest examples, there is evidence of a "common form", which is adapted during the thirteenth century in the largest households to record consumption as well as purchases. In the fourteenth century in the largest households, probably preceded by developments in the English royal household and the monasteries, the diet account became a sophisticated instrument of domestic management. There is considerable variation in the account between households, the largest households having separate departmental and wardrobe accounts. To use the diet account for planning and budgetting, it was necessary to have a summary of its contents. From the 1320s and particularly in the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, emphasis was placed on an annual cash, corn and stock account, similar in form to the manorial account, to be set beside the accounts of receivers general and valors to give an overview of the finances of the administration. In the smallest households there is little development in form. -

English Monks Suppression of the Monasteries

ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES ENGLISH MONKS and the SUPPRESSION OF THE MONASTERIES by GEOFFREY BAS KER VILLE M.A. (I) JONA THAN CAPE THIRTY BEDFORD SQUARE LONDON FIRST PUBLISHED I937 JONATHAN CAPE LTD. JO BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON AND 91 WELLINGTON STREET WEST, TORONTO PRINTED IN GREAT BRITAIN IN THE CITY OF OXFORD AT THE ALDEN PRESS PAPER MADE BY JOHN DICKINSON & CO. LTD. BOUND BY A. W. BAIN & CO. LTD. CONTENTS PREFACE 7 INTRODUCTION 9 I MONASTIC DUTIES AND ACTIVITIES I 9 II LAY INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 45 III ECCLESIASTICAL INTERFERENCE IN MONASTIC AFFAIRS 72 IV PRECEDENTS FOR SUPPRESSION I 308- I 534 96 V THE ROYAL VISITATION OF THE MONASTERIES 1535 120 VI SUPPRESSION OF THE SMALLER MONASTERIES AND THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE 1536-1537 144 VII FROM THE PILGRIMAGE OF GRACE TO THE FINAL SUPPRESSION 153 7- I 540 169 VIII NUNS 205 IX THE FRIARS 2 2 7 X THE FATE OF THE DISPOSSESSED RELIGIOUS 246 EPILOGUE 273 APPENDIX 293 INDEX 301 5 PREFACE THE four hundredth anniversary of the suppression of the English monasteries would seem a fit occasion on which to attempt a summary of the latest views on a thorny subject. This book cannot be expected to please everybody, and it makes no attempt to conciliate those who prefer sentiment to truth, or who allow their reading of historical events to be distorted by present-day controversies, whether ecclesiastical or political. In that respect it tries to live up to the dictum of Samuel Butler that 'he excels most who hits the golden mean most exactly in the middle'. -

All Saints St. Mary's

All Saints St. Mary’s NETTLEHAM PARISH CHURCH RISEHOLME PARISH CHURCH The Good News from Nettleham Sunday 1 March 2020 Lent 1 No 138 Father Richard writes…. This time of Lent is an occasion for fasting, deeper prayerfulness, acts of sacrifice and generosity, and “spring cleaning” our lives as disciples of Jesus Christ. It always is, and this year it somehow seems even more timely. How our world needs the new life of the resurrection, how it needs to understand and confront for the agony of the crucifixion, how it needs us to be disciples who take up the cross to follow the Lord! Clergy and licensed readers have had a lengthy letter from our two bishops, Bishop David and Bishop Nicholas, commending to us a greater emphasis on prayerfulness, sacrifice, cleansing, re-committing, openness to the light of Christ, both as searchlight in our dark corners and as guide to a better future. They refer to the awful burden of our history as a diocese that is progressively being revealed. They talk of the challenge of a year with our Diocesan Bishop and our Cathedral Dean stepped back from ministry. They talk of the challenge to the very future of our diocese and its churches from declining numbers, and from a yawning gap in our finances. This latter is now so urgent – you may have seen it has made it onto the BBC and the Lincolnite – that we no longer have a do-nothing option. It isn’t all about money. The church across the county is losing members quite fast, and with the average age being pretty high, especially in rural areas, we are sitting on a demographic time-bomb.