Evolution of the Muscles of Facial Expression in a Monogamous Ape: Evaluating the Relative Influences of Ecological and Phylogenetic Factors in Hylobatids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

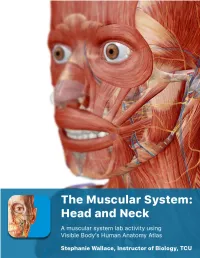

The Muscular System Views

1 PRE-LAB EXERCISES Before coming to lab, get familiar with a few muscle groups we’ll be exploring during lab. Using Visible Body’s Human Anatomy Atlas, go to the Views section. Under Systems, scroll down to the Muscular System views. Select the view Expression and find the following muscles. When you select a muscle, note the book icon in the content box. Selecting this icon allows you to read the muscle’s definition. 1. Occipitofrontalis (epicranius) 2. Orbicularis oculi 3. Orbicularis oris 4. Nasalis 5. Zygomaticus major Return to Muscular System views, select the view Head Rotation and find the following muscles. 1. Sternocleidomastoid 2. Scalene group (anterior, middle, posterior) 2 IN-LAB EXERCISES Use the following modules to guide your exploration of the head and neck region of the muscular system. As you explore the modules, locate the muscles on any charts, models, or specimen available. Please note that these muscles act on the head and neck – those that are located in the neck but act on the back are in a separate section. When reviewing the action of a muscle, it will be helpful to think about where the muscle is located and where the insertion is. Muscle physiology requires that a muscle will “pull” instead of “push” during contraction, and the insertion is the part that will move. Imagine that the muscle is “pulling” on the bone or tissue it is attached to at the insertion. Access 3D views and animated muscle actions in Visible Body’s Human Anatomy Atlas, which will be especially helpful to visualize muscle actions. -

Axis Scientific Skull with Muscle Origins and Insertions A-108851

Axis Scientific Skull with Muscle Origins and Insertions A-108851 *Muscle Origins = RED Anterior View Occipital Bone Posterior View *Muscle Insertions = BLUE Posterior Cerebral Artery Frontal Bone Basilar Artery Pontine Arteries Parietal Bone Nasal Bone Temporal Bone Sphenoid Bone Temporalis Parietal Bone Occipitofrontalis Occipital Bone Lacrimal Bone Sternocleidomastoid Trapezius Temporalis Semispinalis Capitis Temporal Bone Corrugator Supercilii Splenius Capitis Longissimus Capitis Orbicularis Oculi Obliquus Capitis Superior Temporal Basilar Artery Bone Procerus Rectis Capitis C1 Posterior Major Vertebral Artery Levator Labii Superioris C2 Alaeque Nasi Rectis Capitis Posterior Minor Sphenoid Levator Labii Superioris Posterior Digastric Zygomatic Bone Bone C3 Nasalis (Transverse Part) Rectis Capitis C4 Masseter Lateralis Spinal Nerve Zygomaticus Major C5 Zygomatic Medial Pterygoid Bone Zygomaticus Minor C6 Temporalis Mylohyoid C7 Mandible Levator Anguli Oris Vomer Nasalis (Alar Part) Spinal Nerve Spinal Cord Maxilla Orbicularis Oris Depressor Septi Nasi Masseter Medial Superior Masseter Mandible Orbicularis Oris Constrictor Pterygoid Inferior View Styloglossus Platysma Mylohyoid Depressor Stylohyoid Anguli Oris Anterior Stylopharyngeus Spinal Nerve Depressor Digastric Labii Inferioris Posterior Geniohyoid Digastric Vertebral Artery Mentalis Rectis Capitis Genioglossus Lateralis Rectis Capitis Buccinator Mandible Posterior Major Rectis Capitis Posterior Minor Frontal Bone Corrugator Supercilii Orbicularis Oculi Lacrimal Bone Depressor -

Questions on Human Anatomy

Standard Medical Text-books. ROBERTS’ PRACTICE OF MEDICINE. The Theory and Practice of Medicine. By Frederick T. Roberts, m.d. Third edi- tion. Octavo. Price, cloth, $6.00; leather, $7.00 Recommended at University of Pennsylvania. Long Island College Hospital, Yale and Harvard Colleges, Bishop’s College, Montreal; Uni- versity of Michigan, and over twenty other medical schools. MEIGS & PEPPER ON CHILDREN. A Practical Treatise on Diseases of Children. By J. Forsyth Meigs, m.d., and William Pepper, m.d. 7th edition. 8vo. Price, cloth, $6.00; leather, $7.00 Recommended at thirty-five of the principal medical colleges in the United States, including Bellevue Hospital, New York, University of Pennsylvania, and Long Island College Hospital. BIDDLE’S MATERIA MEDICA. Materia Medica, for the Use of Students and Physicians. By the late Prof. John B Biddle, m.d., Professor of Materia Medica in Jefferson Medical College, Phila- delphia. The Eighth edition. Octavo. Price, cloth, $4.00 Recommended in colleges in all parts of the UnitedStates. BYFORD ON WOMEN. The Diseases and Accidents Incident to Women. By Wm. H. Byford, m.d., Professor of Obstetrics and Diseases of Women and Children in the Chicago Medical College. Third edition, revised. 164 illus. Price, cloth, $5.00; leather, $6.00 “ Being particularly of use where questions of etiology and general treatment are concerned.”—American Journal of Obstetrics. CAZEAUX’S GREAT WORK ON OBSTETRICS. A practical Text-book on Midwifery. The most complete book now before the profession. Sixth edition, illus. Price, cloth, $6.00 ; leather, $7.00 Recommended at nearly fifty medical schools in the United States. -

Facial-Stapedial Synkinesis Following Acute Idiopathic Facial Palsy

CASE REPORT Facial-Stapedial Synkinesis Following Acute Idiopathic Facial Palsy Michael Hutz, MD; Margaret Aasen; John Leonetti, MD ABSTRACT complete resolution of their unilateral Introduction: While most patients note a complete resolution of facial paralysis in Bell’s Palsy, facial paralysis, the remaining patients up to 30% will have persistent facial weakness and develop synkinesis. All branches of the manifest persistent paralysis or develop facial nerve are at risk for developing synkinesis, but stapedial synkinesis has rarely been synkinesis, which occurs when a volun- reported in the literature. tary muscle movement causes a simulta- Case Presentation: A 45-year-old man presented with sudden onset, complete right facial neous involuntary contraction of other paralysis. One-and-a-half years later, he had persistent facial weakness and synkinesis. He muscles. The facial nerve is the 7th cra- noted persistent right aural fullness and hearing loss. Audiometry demonstrated facial-stapedial nial nerve and is primarily affected in synkinesis. Bell’s Palsy. It acts to control the muscles Discussion: The patient was diagnosed with stapedial synkinesis based on audiometric find- of facial expression and conveys taste sen- ings by comparing his hearing at rest and with sustained facial mimetic movement. A literature sation to the anterior two-thirds of the review revealed 21 reported cases of this disorder. tongue. Faulty facial nerve regeneration fol- Conclusions: Facial-stapedial synkinesis is an underdiagnosed phenomenon for patients recov- ering from idiopathic facial palsy. Patients who develop facial synkinesis also may have a com- lowing Bell’s Palsy commonly leads to ponent of stapedial synkinesis and should be referred to an otolaryngologist if they complain abnormal muscle contractions of the eye, of any otologic symptoms, such as unilateral hearing loss or tinnitus. -

EDS Awareness in the TMJ Patient

EDS Awareness in the TMJ Patient TMJ and CCI with the EDS Patient “The 50/50” Myofascial Pain Syndrome EDNF, Baltimore, MD August 14,15, 2015 Generation, Diagnosis and Treatment of Head Pain of Musculoskeletal Origin Head pain generated by: • Temporomandibular joint dysfunction • Cervicocranial Instability • Mandibular deviation • Deflection of the Pharyngeal Constrictor Structures Parameters & Observations . The Myofascial Pain Syndrome (MPS) is a description of pain tracking in 200 Ehlers-Danlos patients. Of the 200 patients, 195 were afflicted with this pain referral syndrome pattern. The MPS is in direct association and correlation to Temporomandibular Joint dysfunction and Cervico- Cranial Instability syndromes. Both syndromes are virtually and always correlated. Evaluation of this syndrome was completed after testing was done to rule out complex or life threatening conditions. The Temporomandibular Joint TMJ Dysfunction Symptoms: Deceptively Simple, with Complex Origins 1) Mouth opening, closing with deviation of mandibular condyles. -Menisci that maybe subluxated causing mandibular elevation. -Jaw locking “open” or “closed”. -Inability to “chew”. 2) “Headaches”/”Muscles spasms” (due to decreased vertical height)generated in the temporalis muscle, cheeks areas, under the angle of the jaw. 3) Osseous distortion Pain can be generated in the cheeks, floor of the orbits and/or sinuses due to osseous distortion associated with “bruxism”. TMJ dysfunction cont. (Any of the following motions may produce pain) Pain With: . Limited opening(closed lock): . Less than 33 mm of rotation in either or both joints . Translation- or lack of . Deviations – motion of the mandible to the affected side or none when both joints are affected . Over joint pain with or without motion around or . -

The Articulatory System Chapter 6 Speech Science/ COMD 6305 UTD/ Callier Center William F. Katz, Ph.D

The articulatory system Chapter 6 Speech Science/ COMD 6305 UTD/ Callier Center William F. Katz, Ph.D. STRUCTURE/FUNCTION VOCAL TRACT CLASSIFICATION OF CONSONANTS AND VOWELS MORE ON RESONANCE ACOUSTIC ANALYSIS/ SPECTROGRAMS SUPRSEGMENTALS, COARTICULATION 1 Midsagittal dissection From Kent, 1997 2 Oral Cavity 3 Oral Structures – continued • Moistened by saliva • Lined by mucosa • Saliva affected by meds 4 Tonsils • PALATINE* (laterally – seen in oral periph • LINGUAL (inf.- root of tongue) • ADENOIDS (sup.) [= pharyngeal] • Palatine, lingual tonsils are larger in children • *removed in tonsillectomy 5 Adenoid Facies • Enlargement from infection may cause problems (adenoid facies) • Can cause problems with nasal sounds or voicing • Adenoidectomy; also tonsillectomy (for palatine tonsils) 6 Adenoid faces (example) 7 Oral structures - frenulum Important component of oral periphery exam Lingual frenomy – for ankyloglossia “tongue-tie” Some doctors will snip for infants, but often will loosen by itself 8 Hard Palate Much variability in palate shape and height Very high vault 9 Teeth 10 Dentition - details Primary (deciduous, milk teeth) Secondary (permanent) n=20: n=32: ◦ 2 incisor ◦ 4 incisor ◦ 1 canine ◦ 2 canine ◦ 2 molar ◦ 4 premolar (bicuspid) Just for “fun” – baby ◦ 6 molar teeth pushing in! NOTE: x 2 for upper and lower 11 Types of malocclusion • Angle’s classification: • I, II, III • Also, individual teeth can be misaligned (e.g. labioversion) Also “Neutrocclusion/ distocclusion/mesiocclusion” 12 Dental Occlusion –continued Other terminology 13 Mandible Action • Primary movements are elevation and depression • Also…. protrusion/retraction • Lateral grinding motion 14 Muscles of Jaw Elevation Like alligators, we are much stronger at jaw elevation (closing to head) than depression 15 Jaw Muscles ELEVATORS DEPRESSORS •Temporalis ✓ •Mylohyoid ✓ •Masseter ✓ •Geniohyoid✓ •Internal (medial) Pterygoid ✓ •Anterior belly of the digastric (- Kent) •Masseter and IP part of “mandibular sling” •External (lateral) pterygoid(?)-- also protrudes and rocks side to side. -

Head & Neck Muscle Table

Robert Frysztak, PhD. Structure of the Human Body Loyola University Chicago Stritch School of Medicine HEAD‐NECK MUSCLE TABLE PROXIMAL ATTACHMENT DISTAL ATTACHMENT MUSCLE INNERVATION MAIN ACTIONS BLOOD SUPPLY MUSCLE GROUP (ORIGIN) (INSERTION) Anterior floor of orbit lateral to Oculomotor nerve (CN III), inferior Abducts, elevates, and laterally Inferior oblique Lateral sclera deep to lateral rectus Ophthalmic artery Extra‐ocular nasolacrimal canal division rotates eyeball Inferior aspect of eyeball, posterior to Oculomotor nerve (CN III), inferior Depresses, adducts, and laterally Inferior rectus Common tendinous ring Ophthalmic artery Extra‐ocular corneoscleral junction division rotates eyeball Lateral aspect of eyeball, posterior to Lateral rectus Common tendinous ring Abducent nerve (CN VI) Abducts eyeball Ophthalmic artery Extra‐ocular corneoscleral junction Medial aspect of eyeball, posterior to Oculomotor nerve (CN III), inferior Medial rectus Common tendinous ring Adducts eyeball Ophthalmic artery Extra‐ocular corneoscleral junction division Passes through trochlea, attaches to Body of sphenoid (above optic foramen), Abducts, depresses, and medially Superior oblique superior sclera between superior and Trochlear nerve (CN IV) Ophthalmic artery Extra‐ocular medial to origin of superior rectus rotates eyeball lateral recti Superior aspect of eyeball, posterior to Oculomotor nerve (CN III), superior Elevates, adducts, and medially Superior rectus Common tendinous ring Ophthalmic artery Extra‐ocular the corneoscleral junction division -

![FACE and SCALP, MUSCLES of FACIAL EXPRESSION, and PAROTID GLAND (Grant's Dissector [16Th Ed.] Pp](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3635/face-and-scalp-muscles-of-facial-expression-and-parotid-gland-grants-dissector-16th-ed-pp-973635.webp)

FACE and SCALP, MUSCLES of FACIAL EXPRESSION, and PAROTID GLAND (Grant's Dissector [16Th Ed.] Pp

FACE AND SCALP, MUSCLES OF FACIAL EXPRESSION, AND PAROTID GLAND (Grant's Dissector [16th Ed.] pp. 244-252; 254-256; 252-254) TODAY’S GOALS: 1. Identify the parotid gland and parotid duct 2. Identify the 5 terminal branches of the facial nerve (CN VII) emerging from the parotid gland 3. Identify muscles of facial expression 4. Identify principal cutaneous branches of the trigeminal nerve (CN V) 5. Identify the 5 layers of the scalp 6. Identify the facial nerve, retromandibular vein, and external carotid artery within the parotid gland 7. Identify the auriculotemporal nerve and superficial temporal vessels DISSECTION NOTES: General comments: Productive and effective study of the remaining lab sessions on regions of the head requires your attention to and study of the osteology of the skull. The opening pages of this section in Grant’s Dissector contains images and labels of the skull and parts thereof. Utilize atlases as additional resources to learn the osteology. Couple viewing of these images with an actual skull in hand (available in the lab) to achieve mastery of this material. Incorporate the relevant osteology to a synthesis of the area being covered. This lab session introduces you to the face and scalp, the major cutaneous nerves (branches of the trigeminal nerve [CN V]) that supply the skin of the face and scalp, and important muscles of facial expression. Some helpful overview comments to consider as you begin this study include: • The skin of the face is quite thin and mobile except where it is firmly attached to the nose and -

The Structure and Movement of Clarinet Playing D.M.A

The Structure and Movement of Clarinet Playing D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sheri Lynn Rolf, M.D. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee: Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Chair Dr. David Hedgecoth Professor Katherine Borst Jones Dr. Scott McCoy Copyrighted by Sheri Lynn Rolf, M.D. 2018 Abstract The clarinet is a complex instrument that blends wood, metal, and air to create some of the world’s most beautiful sounds. Its most intricate component, however, is the human who is playing it. While the clarinet has 24 tone holes and 17 or 18 keys, the human body has 205 bones, around 700 muscles, and nearly 45 miles of nerves. A seemingly endless number of exercises and etudes are available to improve technique, but almost no one comments on how to best use the body in order to utilize these studies to maximum effect while preventing injury. The purpose of this study is to elucidate the interactions of the clarinet with the body of the person playing it. Emphasis will be placed upon the musculoskeletal system, recognizing that playing the clarinet is an activity that ultimately involves the entire body. Aspects of the skeletal system as they relate to playing the clarinet will be described, beginning with the axial skeleton. The extremities and their musculoskeletal relationships to the clarinet will then be discussed. The muscles responsible for the fine coordinated movements required for successful performance on the clarinet will be described. -

Electromyographic Analysis of the Orbicularis Oris Muscle in Oralized Deaf Individuals

Braz Dent J (2005) 16(3): 237-242 Electromyography in deaf individuals ISSN 0103-6440237 Electromyographic Analysis of the Orbicularis Oris Muscle in Oralized Deaf Individuals Simone Cecílio Hallak REGALO1 Mathias VITTI1 Maria Tereza Bagaiolo MORAES2 Marisa SEMPRINI1 Cláudia Maria de FELÍCIO2 Maria da Glória Chiarello de MATTOS3 Jaime Eduardo Cecílio HALLAK4 Carla Moreto SANTOS3 1Department of Morphology, Stomatology and Physiology, Faculty of Dentistry of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil 2Department of Speech Pathology and Audiology, University of Ribeirão Preto (UNAERP), Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil 3Department of Dental Materials and Prosthodontics, Faculty of Dentistry of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil 4Department of Neuropsychiatry and Psychological Medicine, Medical School of Ribeirão Preto, University of São Paulo, Ribeirão Preto, SP, Brazil; Neuroscience and Psychiatry Unit, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK Electromyography has been used to evaluate the performance of the peribuccal musculature in mastication, swallowing and speech, and is an important tool for analysis of physiopathological changes affecting this musculature. Many investigations have been conducted in patients with auditory and speech deficiencies, but none has evaluated the musculature responsible for the speech. This study compared the electromyographic measurements of the superior and inferior fascicles of the orbicularis oris muscle in patients with profound bilateral neurosensorial hearing deficiency (deafness) and healthy volunteers. Electromyographic analysis was performed on recordings from 20 volunteers (mean age of 18.5 years) matched for gender and age. Subjects were assigned to two groups, as follows: a group formed by 10 individuals with profound bilateral neurosensorial hearing deficiency (deaf individuals) and a second group formed by 10 healthy individuals (hearers). -

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS Infection Spread Determinants

ODONTOGENTIC INFECTIONS The Host The Organism The Environment In a state of homeostasis, there is Peter A. Vellis, D.D.S. a balance between the three. PROGRESSION OF ODONTOGENIC Infection Spread Determinants INFECTIONS • Location, location , location 1. Source 2. Bone density 3. Muscle attachment 4. Fascial planes “The Path of Least Resistance” Odontogentic Infections Progression of Odontogenic Infections • Common occurrences • Periapical due primarily to caries • Periodontal and periodontal • Soft tissue involvement disease. – Determined by perforation of the cortical bone in relation to the muscle attachments • Odontogentic infections • Cellulitis‐ acute, painful, diffuse borders can extend to potential • fascial spaces. Abscess‐ chronic, localized pain, fluctuant, well circumscribed. INFECTIONS Severity of the Infection Classic signs and symptoms: • Dolor- Pain Complete Tumor- Swelling History Calor- Warmth – Chief Complaint Rubor- Redness – Onset Loss of function – Duration Trismus – Symptoms Difficulty in breathing, swallowing, chewing Severity of the Infection Physical Examination • Vital Signs • How the patient – Temperature‐ feels‐ Malaise systemic involvement >101 F • Previous treatment – Blood Pressure‐ mild • Self treatment elevation • Past Medical – Pulse‐ >100 History – Increased Respiratory • Review of Systems Rate‐ normal 14‐16 – Lymphadenopathy Fascial Planes/Spaces Fascial Planes/Spaces • Potential spaces for • Primary spaces infectious spread – Canine between loose – Buccal connective tissue – Submandibular – Submental -

Atlas of the Facial Nerve and Related Structures

Rhoton Yoshioka Atlas of the Facial Nerve Unique Atlas Opens Window and Related Structures Into Facial Nerve Anatomy… Atlas of the Facial Nerve and Related Structures and Related Nerve Facial of the Atlas “His meticulous methods of anatomical dissection and microsurgical techniques helped transform the primitive specialty of neurosurgery into the magnificent surgical discipline that it is today.”— Nobutaka Yoshioka American Association of Neurological Surgeons. Albert L. Rhoton, Jr. Nobutaka Yoshioka, MD, PhD and Albert L. Rhoton, Jr., MD have created an anatomical atlas of astounding precision. An unparalleled teaching tool, this atlas opens a unique window into the anatomical intricacies of complex facial nerves and related structures. An internationally renowned author, educator, brain anatomist, and neurosurgeon, Dr. Rhoton is regarded by colleagues as one of the fathers of modern microscopic neurosurgery. Dr. Yoshioka, an esteemed craniofacial reconstructive surgeon in Japan, mastered this precise dissection technique while undertaking a fellowship at Dr. Rhoton’s microanatomy lab, writing in the preface that within such precision images lies potential for surgical innovation. Special Features • Exquisite color photographs, prepared from carefully dissected latex injected cadavers, reveal anatomy layer by layer with remarkable detail and clarity • An added highlight, 3-D versions of these extraordinary images, are available online in the Thieme MediaCenter • Major sections include intracranial region and skull, upper facial and midfacial region, and lower facial and posterolateral neck region Organized by region, each layered dissection elucidates specific nerves and structures with pinpoint accuracy, providing the clinician with in-depth anatomical insights. Precise clinical explanations accompany each photograph. In tandem, the images and text provide an excellent foundation for understanding the nerves and structures impacted by neurosurgical-related pathologies as well as other conditions and injuries.