CONFIDENTIAL Public Disclosure Authorized

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Africa's Freedom Railway

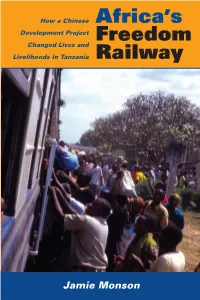

AFRICA HistORY Monson TRANSPOrtatiON How a Chinese JamiE MONSON is Professor of History at Africa’s “An extremely nuanced and Carleton College. She is editor of Women as On a hot afternoon in the Development Project textured history of negotiated in- Food Producers in Developing Countries and Freedom terests that includes international The Maji Maji War: National History and Local early 1970s, a historic Changed Lives and Memory. She is a past president of the Tanzania A masterful encounter took place near stakeholders, local actors, and— Studies Assocation. the town of Chimala in Livelihoods in Tanzania Railway importantly—early Chinese poli- cies of development assistance.” the southern highlands of history of the Africa —James McCann, Boston University Tanzania. A team of Chinese railway workers and their construction “Blessedly economical and Tanzanian counterparts came unpretentious . no one else and impact of face-to-face with a rival is capable of writing about this team of American-led road region with such nuance.” rail power in workers advancing across ’ —James Giblin, University of Iowa the same rural landscape. s Africa The Americans were building The TAZARA (Tanzania Zambia Railway Author- Freedom ity) or Freedom Railway stretches from Dar es a paved highway from Dar Salaam on the Tanzanian coast to the copper es Salaam to Zambia, in belt region of Zambia. The railway, built during direct competition with the the height of the Cold War, was intended to redirect the mineral wealth of the interior away Chinese railway project. The from routes through South Africa and Rhodesia. path of the railway and the After being rebuffed by Western donors, newly path of the roadway came independent Tanzania and Zambia accepted help from communist China to construct what would together at this point, and become one of Africa’s most vital transportation a tense standoff reportedly corridors. -

1 TANZANIA & ZANZIBAR DIARY Dates: 24Th June 2009 to 6Th

TANZANIA & ZANZIBAR DIARY Dates: 24th June 2009 to 6th August 2009 43 Days Tanzania miles = 3016 miles (4826 km) Trip miles = 12835 miles (20536 km) Day 136 - Wednesday 24th June CONTINUED Zambia to Tanzania First stop at the Tunduma border was the Tanzanian immigration: fill out the entry forms and hand over with passports to one official; then hand over US$50 each for visas to another official and then waited and waited. Judi stayed on whist I went to the customs desk to get the carnet stamped up; ‘anything to declare?’ He gave me a funny look when I said no but he accepted it. Apart from exiting South Africa in March, nobody has even seen the vehicle let alone look at it or inspect it. Next stop, road fund licence, US$20, and fuel levy, US$5: closed, gone to lunch. And this is the only commercial international border crossing between Zambia and East Africa! Back to the vehicle where an insurance certificate and windscreen sticker had been prepared for us for another US$70 for three months; my advisor assured me it would have been US$70 for just one day. I believed him as he was my trusty personal advisor! Against all advice we decided to change some pounds for Tanzanian shillings as we probably couldn’t do this at a bank; we knew the rate would be poor but I left Judi to it. I was still waiting for the office to open when I heard a familiar car alarm go off. I wandered back to the vehicle to find Judi, who had locked the doors on the fob rather than door button, inside but had moved to get some water as it was hot and set the alarm off! She was a bit upset as she thought she had been diddled on the exchange rate by a factor of 10. -

Tanzania: Tanzam Highway Rehabilitation

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP TANZANIA: TANZAM HIGHWAY REHABILITATION Project Performance Evaluation Report (PPER) OPERATIONS EVALUATION DEPARTMENT (OPEV) 8 March 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Currency Equivalents i Acronyms and Abbreviations i Preface ii Basic Project Data iii Executive Summary vi Summary of Ratings ix 1. THE PROJECT 1 1.1 Country and Sector Economic Context 1 1.2 Project Formulation 2 1.3 Project Objectives and Scope at Appraisal 2 1.4 Financing Arrangements - Bank Group and others 3 2. EVALUATION 4 2.1 Evaluation Methodology and Approach 4 2.2 Performance Indicators 4 3. IMPLEMENTATION PERFORMANCE 5 3.1 Loan Effectiveness, Start-up and Implementation 5 3.2 Adherence to Project Costs, Disbursements & Financing Arrangements 6 3.3 Project Management, Reporting, Monitoring and Evaluation Achievements 6 4. PERFORMANCE EVALUATION AND RATINGS 7 4.1 Relevance of Objectives and Quality at Entry 7 4.2 Achievement of Objectives and Outputs. "Efficacy" 8 4.3 Efficiency 9 4.4 Institutional Development Impact 9 4.5 Sustainability 12 4.6 Aggregate Performance Rating 13 4.7 Performance of the Borrower 13 4.8 Bank Performance 13 4.9 Factors affecting Implementation Performance and Outcome 13 5. ECONOMIC INTEGRATION AND REGIONAL CO-OPERATION 14 5.1 Background 14 5.2 Regional Goals at Appraisal 14 5.3 Achievements 14 6. CONCLUSIONS, LESSONS LEARNT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 17 6.1 Conclusions 17 6.2 Lessons learnt 17 6.3 Recommendations 17 TABLES Table 1: Main Aggregates of the Transport and Communications Sector 1 Table 2: Sources of finances -

Background of the Project

Chapter 1 BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT Chapter 1 BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT The TANZAM Highway is an international trunk road that starts from Dar es Salaam, the capital city and largest sea port in Tanzania. It passes through the west of Tanzania and terminates at Lusaka, the capital city of Zambia, having a total length of 1,400 km with the Tanzanian section being about 920 km. The TANZAM Highway not only provides access to sea transport for the landlocked and nationhood countries of Zambia, Malawi and Congo, but also serves as a transportation road for agricultural products and cash crops for export from primary agricultural production areas e.g. Iringa and Mbeya regions in western Tanzania. Agriculture is the mainstay of the economy of these regions and supports the living level of the farmers that make up the majority of the poor population. The highway is nominated as the most important road in Tanzania from the viewpoint of direct benefit to people who live along the road, movement of agricultural products and cash crops, and distribution of physical products. The "Kitonga Gorge" has steep grades and frequent sharp curves for a section of about 10 km in mountainous terrain located on the TANZAM Highway in Iringa region, 450 km from Dar es Salaam. After improvement of the road with an asphalt concrete surface of 2 lanes in 1973, no substantial rehabilitation has been conducted, even though serious deep rutting appeared due to the increase in heavy-vehicle traffic. While other parts of the TANZAM Highway have been rehabilitated by various donor countries, the serviceability of Kitonga Gorge section is very poor and is well-known for its high accident rate because of the damaged road surface, improper drainage facilities, eroded shoulders and inadequate traffic safety facilities The poor condition of the road at Kitonga Gorge has been preventing the vital movement of agricultural products and inputs such as fertiliser. -

Worldwide Road, Tunnel and Bridge Construction Projects Engineered by Nippon Koei

Act with integrity and contribute to society through technology and engineering اﻟﻌﻤﻞ ﺑﻨﺰاھﺔ واﻹﺳﮭﺎم ﻓﻲ ﺑﻨﺎء اﻟﻤﺠﺘﻤﻊ ﻋﻦ طﺮﻳﻖ اﻟﺘﻜﻨﻮﻟﻮﺟﯿﺎ واﻟﮭﻨﺪﺳﺔ Nippon Koei respects the history and culture of each nation and region. We contribute to the sustainable development of societies through excellent technology and engineering appropriate for each region. About Us Tunnels Japanʼs No.1 International Engineering Regional Sales Ratio (2018.6) Tunnel engineering and engineering solutions: Consultants Europe 11.5% Others 0.4% To natural obstacles, offering total tunnel solutions Completed over 5,000 multi-disciplinary Central - South For local economic development though new technologies infrastructure projects in 160 countries America 6.5% Africa 3.6% during 70 years East Asia 1.7% Oldest independent consulting firm in Japan 58.8% Japan, founded in 1946 Asia 17.6% Our solution for the 6,260m long Hai Van Pass Tunnel, one of the 30 largest and most modern tunnels in the world, shortening the travel Roads time from hours to 10 minutes, Vietnam Design and construction management: Bridges From trans-continental highways, Ranging from short-span and low-clearance bridges to high-capacity high-speed urban long-span, high-elevation and structurally complex bridges highways and viaducts to rural crossing great rivers and straits roads Dawbon Bridge, PC 3span For enhancing the security of Continuous Extradosed Bridge inhabitants and encouraging socio of 220m (60m+100m+60m) with Steel Pipe Sheet Pile Foundation crossing Upper Before and After the Construction -

Narrative Section of a Successful Application

Narrative Section of a Successful Application The attached document contains the grant narrative and selected portions of a previously funded grant application. It is not intended to serve as a model, but to give you a sense of how a successful application may be crafted. Every successful application is different, and each applicant is urged to prepare a proposal that reflects its unique project and aspirations. Prospective applicants should consult the Research Programs application guidelines at http://www.neh.gov/grants/research/collaborative-research-grants for instructions. Applicants are also strongly encouraged to consult with the NEH Division of Research Programs staff well before a grant deadline. Note: The attachment only contains the grant narrative and selected portions, not the entire funded application. In addition, certain portions may have been redacted to protect the privacy interests of an individual and/or to protect confidential commercial and financial information and/or to protect copyrighted materials. Project Title: Technology Transfer at Work in China-Africa Development Assistance: The TAZARA Railway, 1968-1986 Institution: Macalester College (Grant originally awarded to Carleton College and transferred in 2009 to Macalester College) Project Director: Jamie Monson Grant Program: Collaborative Research 1100 Pennsylvania Ave., N.W., Rm. 318, Washington, D.C. 20506 P 202.606.8200 F 202.606.8204 E [email protected] www.neh.gov STATEMENT OF PROJECT SIGNIFICANCE AND IMPACT This research project will examine the history of work and technology transfer during the construction of the TAZARA railway (the acronym stands for Tanzania Zambia Railway Authority), a project that was built and operated with Chinese development assistance in East Africa between 1968 and 1986. -

World Bank Document

RESTRICTED Report No. TO-676a This report Public Disclosure Authorized was prepared for use within the Bank and its affiliated organizations. They do not accept responsibility for its accuracy or completeness. The report may not be published nor may it be quoted as representing their views. INTERNATIONAL BANK FOR RECONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT ASSOCIATION Public Disclosure Authorized APPRAISAL OF THE SECOND HIGHWAY PROJECT ZAMBIA r" --. I-Uc 1 Public Disclosure Authorized September 10, 1968 Public Disclosure Authorized Projects Department CURRENCY EQUIVALENTS Currency Unit: Kwacha US.$L - K 0.71b Kl - US$1.O40 K1,000,000 = US$1,h00,000 FISCAL YEAR January 1 - December 31 WEIGHTS AND MEASURES British METRIC - BRITISH/US EQUIVALENTS 1 mile = 1.6 kilometers 1 foot = 30.5 centimeters 1 acre = 0.41 hectares 1 imperial gallon = 1.20 US gallons = &.54 liters 1 ton = 1.12 US sh ton = 1.02 metric ton ZAMBIA APPRAISAL OF THE SECOND HIGHWAY PROJECT Table of Contents Page SUItThARY i 1. INTRODUCTION 1 2. BACKGROUND 2 A. Economic Setting 2 B. Transport System 3 C. The Zambia-Tanzania Transport Problem 4 3. THE HIGWRAY SYSTEM 9 A. The Highway System 9 B. Highway Traffic and Vehicle Fleet 9 C. Highway Transport Industry 10 D. Highway Administration 10 E. Design Standards, Engineering and Construction 11 F. Highway Maintenance 11 G. Highway Expenditures and Investment Planning 12 THE PROJECT A. Description 13 B. Design Standards 13 C. Cost Estimates 14 D. Execution 15 E. Financing 15 5. ECONO0MIC E7ALUATION 17 A. Introduction 17 B. Economic Justification 17 C. Problems of Analysis 17 D. -

China and Transport Infrastructure Projects in the SADC Region

Chapter 8 Tying the region together or tearing it apart? China and transport infrastructure projects in the SADC region Sören Scholvin and Georg Strüver 1 1. Introduction China and Africa appear to be economically and politically highly compatible partners: Africa has the resources that China urgently needs. China possesses the means to develop Africa’s transport infrastructure, whose poor condition hampers economic development (Foster et al., 2009: 29-51). Moreover, many ruling elites in Africa are more than reluctant to bow to Western conditions of foreign aid and investment such as good governance, including the rule of the law and transparency. China also attaches conditions to its partnership with Africa, too – most importantly the adherence to the one-China principle. Despite this provision, China’s development assistance and granting of preferential loans is less contingent on political conditions. Commercial interests matter to the People’s Republic. These appear to be easier to accept for African governments (Brown, 2012: 42). As we show in this chapter, China’s interest in transport infrastructure projects in East and Southern Africa is practically always the same: Chinese loans open the door for Chinese enterprises, which then gain key roles in local markets. At the same time, China secures access to important resources. At least in the case of the Sino-Congolese ‘minerals-for- infrastructure deal’, it is publicly known that off-market access to resources has been prescribed in according agreements as the way to repay the Chinese -

Colonial and Postcolonial Logistics Giulia Scotto

69 Colonial and Postcolonial Logistics Giulia Scotto Introduction In the second part of the article, I show how, after This article addresses the logistical aspects of independence, Zambia dealt with a complex geopo- colonial and postcolonial governmental practices litical entanglement, partially inherited from colonial and the way in which such practices structured the planning and partially generated by the end of direct African territory. In particular, it focuses on Zambia forms of imperialism, which required the rerouting (Northern Rhodesia at time of British domination), a of the export and import of resources and the rebal- landlocked country located in the centre of Southern ancing of uneven territorial structures. To do so, the Africa, whose historical evolution, since it was postcolonial nation state re-applied the instruments conquered at the beginning of the twentieth century, inherited by the ‘colonial logistic’ but, for lack of is deeply intertwined with the discovery, extraction resources and expertise, it opened the door to a set and export of copper and with the import of fossil of international patrons. fuel. It does so by presenting a series of episodes of Zambian history, from its foundation until the early The analysis of infrastructure development in postcolonial phase. postcolonial Zambia illustrates the competing strat- egies through which imperialist powers attempted In the first part of the text, I introduce the concept to secure a new form of control on Africa and eluci- of ‘colonial logistics’ intended as the modification of dates the role of logistics as a decisive tool to shape territories for military and political domination, and the African territory at the various scales. -

Chapter 2 CONTENTS of the PROJECT

Chapter 2 CONTENTS OF THE PROJECT Chapter 2 CONTENTS OF THE PROJECT 2-1 Basic Concept of the Project (1) National Development Plan and Objectives of the Project The TANZAM Highway (Dar es Salaam, Morogoro, Iringa, Mbeya, Zambia) is an international trunk road which starts from the Dar es Salaam, the capital and the largest sea port in Tanzania, and ends at Lusaka, the capital of Zambia. The total length of the Highway is 1,400km and it passes through Iringa and Mbeya Regions, the principal agricultural production area in Tanzania. The TANZAM Highway also serves as an outlet of sea transport for the neighbouring countries of Zambia, Malawi and Congo. The Project is rehabilitation of a part of the TANZAM Highway in the Kitonga Gorge located 450km west of Dar es Salaam. The Project road will serves as an access road for one of the most prominent agricultural areas which produce 15% of the total agricultural products and 7.4% of the total cash crops in Tanzania. Agriculture is the mainstay of the economy of Tanzania and the sector contributed approximately half of the GDP. The agricultural sector employed 90% of the working population and its export value amounted to over 70% of the total export value. Development of the agriculture sector is very important for both the national economic growth and improvement of the living level of the farmers that comprises majority of the poor population in Tanzania. In the Poverty Reduction Strategy Paper (PRSP), the agriculture sector is considered to be the key component for reduction of the poverty and improvement of the socio-economic indices and given the highest priority in the national policy and reforms. -

Tanzania National Roads Agency (TANROADS)

Tanzania National Roads Agency (TANROADS) Transport Sector Support Project 2 (TSSP 2) Public Disclosure Authorized Airtel Building, Ally Hassan Mwinyi/Kawawa Roads Junction, P.O. Box 11364, Dar es Salaam, Tel: +255 22 21525776/2151639, Fax: +255 22 2150022, Email: [email protected] Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan for Properties to be affected by Rehabilitation of Mafinga to Igawa Road (142km) in Iringa and Mbeya Regions Public Disclosure Authorized Public Disclosure Authorized Prepared by Submitted to National Environment Management Council (NEMC) Public Disclosure Authorized Regent Estate, Regent Street, P.O. Box 63154, Dar es Salaam Tel: 255 (022)2774852; 2774889; Mobile – 0713-608930; Fax- 255 (022) 2774901; Email Address:[email protected] Submission Date: 24th September 2012 Abbreviated RAP for Properties to be affected by Rehabilitation of Mafinga - Igawa Road Section (142 km) of TANZAM Highway Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan for Properties to be affected by the Rehabilitation of Mafinga to Igawa Road (142 km) in Iringa, Njombe and Mbeya Regions Declaration This Abbreviated Resettlement Action Plan report has been prepared by Name and Responsibility Signature Eng. Venant E.K. Rwenyagira - Team Leader and Environmental Management Specialist Mr. Huruma Kisaka – Sociologist Environmental BENCHMARK-Consulting Engineers 2 Abbreviated RAP for Properties to be affected by Rehabilitation of Mafinga - Igawa Road Section (142 km) of TANZAM Highway Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................................................ -

The Tanzania- Zambia Railway Authority (TAZARA)

From the freedom struggle to a fight for economic survival – the Tanzania- Zambia Railway Authority (TAZARA) Tim Zajontz. “The TAZARA of today is no longer what it used to be”, explains Robert (name altered) to me. I met him at a railway crossing not far from Ishitu in Zambia’s Northern Province. He has been working for the bi-national railway corporation for 25 years. We both gaze at the remains of a derailed cargo train. Robert reports that derailments have become more frequent in recent years, just like month- long non-payments of salaries to the 2,797 TAZARA employees. Yet, he also remembers the glory days of the “Uhuru Railway” – the Freedom Railway. Indeed, the history of the TAZARA, which links the port city of Dar es Salaam with Kapiri Mposhi in Zambia’s Central Province, is exceptional. In an attempt to decrease the dependency of Zambia and newly independent neighbouring states from transport routes through Ian Smith’s Rhodesia and Apartheid-South Africa, TAZARA’s founding fathers, Julius Nyerere and Dr. Kenneth Kaunda, embarked on a monumental infrastructural project. They found a committed development partner in Mao’s China, after several requests for aid – amongst others vis-à-vis West Germany, the UK, Japan, the US, the Soviet Union and the World Bank – had come to nothing due to Cold War geopolitics. With much anti-imperial fanfare, 38,000 local and 13,500 Chinese workers built 22 tunnels, 320 bridges, 93 train stations and 1,860,5 kilometres of rail line across topographically challenging terrain. The loss of the lives of 160 workers during the construction from 1970 to 1975 has not adversely affected the pathos surrounding the Sino- African ‘friendship project’.