What Drives Regional Economic Integration?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Review of the Effectiveness of Rail Concessions in the SADC Region

Technical Report: Review of the Effectiveness of Rail Concessions in the SADC Region Larry Phipps, Short-term Consultant Submitted by: AECOM Submitted to: USAID/Southern Africa Gaborone, Botswana March 2009 USAID Contract No. 690-M-00-04-00309-00 (GS 10F-0277P) P.O. Box 602090 ▲Unit 4, Lot 40 ▲ Gaborone Commerce Park ▲ Gaborone, Botswana ▲ Phone (267) 390 0884 ▲ Fax (267) 390 1027 E-mail: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY............................................................................................. 4 2. INTRODUCTION......................................................................................................... 8 2.1 Background .......................................................................................................... 8 2.2 Objectives of Study .............................................................................................. 9 2.3 Study Methodology .............................................................................................. 9 2.4 Report Structure................................................................................................. 10 3. BEITBRIDGE BULAWAYO RAILWAY CONCESSION ............................................. 11 3.1 Objectives of Privatization .................................................................................. 11 3.2 Scope of Railway Privatization ........................................................................... 11 3.3 Mode of Privatization......................................................................................... -

The Maputo-Witbank Toll Road: Lessons for Development Corridors?

The Maputo-Witbank Toll Road: Lessons for Development Corridors? Development Policy Research Unit University of Cape Town The Maputo-Witbank Toll Road: Lessons for Development Corridors? DPRU Policy Brief No. 00/P5 December 2000 1 DPRU Policy Brief 00/P5 Foreword The Development Policy Research Unit (DPRU), located within the University of Cape Town’s School of Economics, was formed in 1990 to undertake economic policy-oriented research. The aim of the unit’s work is the achievement of more effective public policy for industrial development in South and Southern Africa. The DPRU’s mission is to undertake internationally recognised policy research that contributes to the quality and effectiveness of such policy. The unit is involved in research activities in the following areas: · labour markets and poverty · regulatory reform · regional integration These policy briefs are intended to catalyse policy debate. They express the views of their respective authors and not necessarily those of the DPRU. They present the major research findings of the Industrial Strategy Project (ISP). The aim of the ISP is to promote industrial development in the Southern African Development Community (SADC) through regional economic integration and cooperation. It is a three-year project that commenced in August 1998 and is funded by the International Development Research Centre (IDRC). Ultimately, this project will identify the policies and programmes that support regional interactions that contribute to the industrialisation of SADC national economies. This -

Railways: Looking for Traffi C

Chapter11 Railways: Looking for Traffi c frican railroads have changed greatly stock. Moreover, various confl icts and wars in the past 30 years. Back in the 1980s, have rendered several rail sections unusable. A many railway systems carried a large As a result, some networks have closed and share of their country’s traffi c because road many others are in relatively poor condition, transport was poor or faced restrictive regu- with investment backlogs stretching back over lations, and rail customers were established many years. businesses locked into rail either through Few railways are able to generate signifi - physical connections or (if they were para- cant funds for investment. Other than for statals) through policies requiring them to use purely mineral lines, investment has usually a fellow parastatal. Since then, most national come from bilateral and multilateral donors. economies and national railways have been Almost all remaining passenger services fail liberalized. Coupled with the general improve- to cover their costs, and freight service tariffs ment in road infrastructure, liberalization has are constrained by road competition. More- led to strong intermodal competition. Today, over, as long as the railways are government few railways outside South Africa, other than operated, bureaucratic constraints and lack dedicated mineral lines, are essential to the of commercial incentives will prevent them functioning of the economy. from competing successfully. Since 1993, sev- Rail networks in Africa are disconnected, eral governments in Africa have responded by and many are in poor condition. Although concessioning their systems, often accompa- an extensive system based in southern Africa nied by a rehabilitation program funded by reaches as far as the Democratic Republic of international fi nancial institutions. -

Maputo, Mozambique Casenote

Transforming Urban Transport – The Role of Political Leadership TUT-POL Sub-Saharan Africa Final Report October 2019 Case Note: Maputo, Mozambique Lead Author: Henna Mahmood Harvard University Graduate School of Design 1 Acknowledgments This research was conducted with the support of the Volvo Foundation for Research and Education. Principal Investigator: Diane Davis Senior Research Associate: Lily Song Research Coordinator: Devanne Brookins Research Assistants: Asad Jan, Stefano Trevisan, Henna Mahmood, Sarah Zou 2 MAPUTO, MOZAMBIQUE MOZAMBIQUE Population: 27,233,789 (as of July 2018) Population Growth Rate: 2.46% (2018) Median Age: 17.3 GDP: USD$37.09 billion (2017) GDP Per Capita: USD$1,300 (2017) City of Intervention: Maputo Urban Population: 36% of total population (2018) Urbanization Rate: 4.35% annual rate of change (2015-2020 est.) Land Area: 799,380 sq km Roadways: 31,083 km (2015) Paved Roadways: 7365 km (2015) Unpaved Roadways: 23,718 km (2015) Source: CIA Factbook I. POLITICS & GOVERNANCE A. Multi- Scalar Governance Sixteen years following Mozambique’s independence in 1975 and civil war (1975-1992), the government of Mozambique began to decentralize. The Minister of State Administration pushed for greater citizen involvement at local levels of government. Expanding citizen engagement led to the question of what role traditional leaders, or chiefs who wield strong community influence, would play in local governance.1 Last year, President Filipe Nyusi announced plans to change the constitution and to give political parties more power in the provinces. The Ministry of State Administration and Public Administration are also progressively implementing a decentralization process aimed at transferring the central government’s political and financial responsibilities to municipalities (Laws 2/97, 7-10/97, and 11/97).2 An elected Municipal Council (composed of a Mayor, a Municipal Councilor, and 12 Municipal Directorates) and Municipal Assembly are the main governing bodies of Maputo. -

Africa's Freedom Railway

AFRICA HistORY Monson TRANSPOrtatiON How a Chinese JamiE MONSON is Professor of History at Africa’s “An extremely nuanced and Carleton College. She is editor of Women as On a hot afternoon in the Development Project textured history of negotiated in- Food Producers in Developing Countries and Freedom terests that includes international The Maji Maji War: National History and Local early 1970s, a historic Changed Lives and Memory. She is a past president of the Tanzania A masterful encounter took place near stakeholders, local actors, and— Studies Assocation. the town of Chimala in Livelihoods in Tanzania Railway importantly—early Chinese poli- cies of development assistance.” the southern highlands of history of the Africa —James McCann, Boston University Tanzania. A team of Chinese railway workers and their construction “Blessedly economical and Tanzanian counterparts came unpretentious . no one else and impact of face-to-face with a rival is capable of writing about this team of American-led road region with such nuance.” rail power in workers advancing across ’ —James Giblin, University of Iowa the same rural landscape. s Africa The Americans were building The TAZARA (Tanzania Zambia Railway Author- Freedom ity) or Freedom Railway stretches from Dar es a paved highway from Dar Salaam on the Tanzanian coast to the copper es Salaam to Zambia, in belt region of Zambia. The railway, built during direct competition with the the height of the Cold War, was intended to redirect the mineral wealth of the interior away Chinese railway project. The from routes through South Africa and Rhodesia. path of the railway and the After being rebuffed by Western donors, newly path of the roadway came independent Tanzania and Zambia accepted help from communist China to construct what would together at this point, and become one of Africa’s most vital transportation a tense standoff reportedly corridors. -

Port of Maputo, Mozambique

CONFERENCE PROGRAMME Transport Evolution presents 13 - 14 May 2019 | Port of Maputo, Mozambique 25+ expert speakers, including: Osório Lucas Chief Executive Officer, Maputo Port Development Company Col. Andre Ciseau Secretary General, Port Management Association of Eastern & Southern Africa (PMAESA) Clive Smith Chief Executive Officer, Walvis Bay Corridor Group, Namibia Johny Smith Chief Executive Officer, TransNamib Holdings Limited, Namibia Boineelo Shubane Director Operations, Botswana Railways, Botswana Building the next generation of ports and rail in Mozambique Host Port Authority: Supported by: Member of: Organised by: Simultaneous conference translation in English and Portuguese will be provided Será disponibilizada tradução simultânea da conferência em Inglês e Português www.transportevolutionmz.com Welcome to the inaugural Mozambique Ports and Rail Evolution Forum Ports and railways are leading economic engines for Mozambique, providing access to import and export markets, driving local job creation, and unlocking opportunities for the development of the local blue economy. Hosted by Maputo Port Development Company, Mozambique Ports and Rail Evolution prepares the region’s ports and railways for the fourth industrial revolution. Day one of the extensive two-day conference will feature a high level keynote comprising of leading African ports and rail authorities and focus on advancing Intra-African trade. We then explore challenges, opportunities and solutions for improving regional integration and connectivity. Concluding the day, attendees will learn from local and international ports authorities and terminal operators about challenges and opportunities for ports development. Day two begins by looking at major commodities that are driving infrastructure development forward and what types of funding and investment opportunities are available. This is followed by a rail spotlight session where we will learn from local and international rail authorities and operators about maintenance and development projects. -

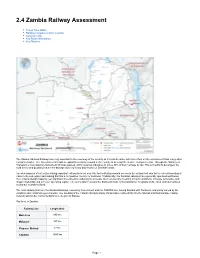

2.4 Zambia Railway Assessment

2.4 Zambia Railway Assessment Travel Time Matrix Railway Companies and Consortia Capacity Table Key Route Information Key Stations The Zambia National Railways are very important to the economy of the country as it is a bulk carrier with less effect on the environment than many other transport modes. The Government intends to expand its railway network in the country to develop the surface transport sector. Through the Ministry of Transport, a new statutory instrument (SI) was passed, which requires industries to move 30% of their carriage by rail. This is in a bid to decongest the road sector and possibly reduce the damage done by heavy duty trucks on Zambian roads. The development of rail routes linking important exit points is not only vital for facilitating smooth access to the outside but also for the overall boosting of trade in the sub-region and making Zambia a competitive country for business. Traditionally, the Zambian railways have generally operated well below their original design capacity, yet significant investment is underway to increase their volumes by investing in track conditions, increase locomotive and wagon availability and increase operating capital. The rail network remains the dominant mode of transportation for goods on the local and international routes but is under-utilized. The main railway lines are the Zambia Railways, owned by Government and the TAZARA line, linking Zambia with Tanzania, and jointly owned by the Zambian and Tanzanian governments. The opening of the Chipata-Mchinji railway link provides connectivity into the Malawi and Mozambique railway network and further connects Zambia to the port of Nacala. -

National Transportation System in the Republic of Zambia

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 1990 National transportation system in the Republic of Zambia Febby Mtonga WMU Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Mtonga, Febby, "National transportation system in the Republic of Zambia" (1990). World Maritime University Dissertations. 877. https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/877 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non- commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WMU LIBRARY WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmo ~ Sweden THE NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA by Febby Mtonga Zambia A paper submitted to the faculty of the World Maritime University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of a MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE in GENERAL MARITIME ADMINISTRATION The views and contents expressed in this paper reflect entirely those of my own and are not to be construed as necessarily endorsed by the University Signed: Date : 0 5 I 11 j S O Assessed by: Professor J. Mlynarcz] World Maritime University Ilf Co-assessed by: U. 2).i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PREFACE i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ii ABBREVIATIONS ... LIST OF MAPS AND APPENDICES iv CHAPTER 1 M • O • o Profile of the Republic of Zambia 1 1.1.0 Geographical Location of Zambia 1.2.0 Population 1.3.0 The Economy 1.3.1 Mining 1.3.2 Agriculture 3 1.3.3 Manufacturing 4 1.3.4 Transportation 7 1. -

1 TANZANIA & ZANZIBAR DIARY Dates: 24Th June 2009 to 6Th

TANZANIA & ZANZIBAR DIARY Dates: 24th June 2009 to 6th August 2009 43 Days Tanzania miles = 3016 miles (4826 km) Trip miles = 12835 miles (20536 km) Day 136 - Wednesday 24th June CONTINUED Zambia to Tanzania First stop at the Tunduma border was the Tanzanian immigration: fill out the entry forms and hand over with passports to one official; then hand over US$50 each for visas to another official and then waited and waited. Judi stayed on whist I went to the customs desk to get the carnet stamped up; ‘anything to declare?’ He gave me a funny look when I said no but he accepted it. Apart from exiting South Africa in March, nobody has even seen the vehicle let alone look at it or inspect it. Next stop, road fund licence, US$20, and fuel levy, US$5: closed, gone to lunch. And this is the only commercial international border crossing between Zambia and East Africa! Back to the vehicle where an insurance certificate and windscreen sticker had been prepared for us for another US$70 for three months; my advisor assured me it would have been US$70 for just one day. I believed him as he was my trusty personal advisor! Against all advice we decided to change some pounds for Tanzanian shillings as we probably couldn’t do this at a bank; we knew the rate would be poor but I left Judi to it. I was still waiting for the office to open when I heard a familiar car alarm go off. I wandered back to the vehicle to find Judi, who had locked the doors on the fob rather than door button, inside but had moved to get some water as it was hot and set the alarm off! She was a bit upset as she thought she had been diddled on the exchange rate by a factor of 10. -

ZAMBIA RAILWAYS LIMTED Zambia As a Link of Africa Through Rail

ZAMBIA RAILWAYS LIMTED Zambia as a link of Africa through Rail TABLE OF CONTENT 1. Brief about Zambia Railways Limited (ZRL) 2. ZRL Regional and Port linkages 3. Greenfield Regional and Port linkages 4. Trade Facilitation 5. Challenges being faced by railways in Africa 6. Possible solutions to Africa’s railway challenges 7. ZRL investment needs 8. Conclusion Brief about ZRL . ZRL is a parastatal railway organization under the Industrial Development Corporation (IDC), mandated to operate both freight and passenger trains. The company is headquartered in Kabwe, Central Province. The main workshops and the CTC are also in Kabwe. Strategic Vision: To be the preferred regional railway transport and logistics provider Strategic Mission: To provide sustainable and competitive rail transport and logistics solutions to customers and deliver shareholder value ZRL Regional and Port linkages Zambia is linked to almost all the trade corridors. Land linked (road and rail) to eight neighbors and beyond the country’s borders. We are a hub. The main trade corridors for Zambia by rail include: .The North-South Corridor .The Dar-es-Salaam Corridor .The Nacala Corridor .The Beira Corridor .Coming up is the Kazungula corridor Shortest route from Ndola is Dar-es-Salaam – 1,976km The longest route is Ndola-Durban – 2,951km. Greenfield regional and Port linkages Livingstone – Kazungula – Mosetse (about 440km). This will reduce transit time by about 12 days on the corridor – one stop border effect. Petauke to Beira (960km) - to connect to Mozambique; Kafue to Lions den - will reduce the distance by rail to South Africa and Mozambique ports by about 1,000km. -

The Significance of Physical Infrastructure in Economic Growth: Maputo Development Corridor

The Significance of Physical Infrastructure in Economic Growth: Maputo Development Corridor LESEGO LETSILE BSc Honours in Urban and Regional Planning 2014 i The Significance of Physical Infrastructure in Economic Growth: Maputo Development Corridor By LESEGO LETSILE Submitted in partial fulfilment for the degree of Bachelor of Science with Honours in Urban and Regional Planning in the School of Architecture and Planning, Faculty of Engineering and the Built Environment at the University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg. ii DECLARATION I declare that unless otherwise indicated in the text, this research report is my own unaided work, and has not been submitted before for any degree or examination to any other university. …………………………………………………………….. Lesego Letsile 22 October 2014 iii To my family and friends iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank God almighty for giving me the strength and perseverance to complete this document. I would also like to thank my mother, Rose Kgomotso Letsile, for her constant support and being a blessing in my life. I would also like to thank my family and friends for their support. I also wish to thank my supervisor, Professor Alison Todes, for her guidance and patience throughout the year. Professor Todes has encouraged me during the most difficult times and her insightful comments have contributed to my ability to enhance the quality of my research. v Contents ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.......................................................................................................... v List of tables -

Tanzania: Tanzam Highway Rehabilitation

AFRICAN DEVELOPMENT BANK GROUP TANZANIA: TANZAM HIGHWAY REHABILITATION Project Performance Evaluation Report (PPER) OPERATIONS EVALUATION DEPARTMENT (OPEV) 8 March 2004 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page No. Currency Equivalents i Acronyms and Abbreviations i Preface ii Basic Project Data iii Executive Summary vi Summary of Ratings ix 1. THE PROJECT 1 1.1 Country and Sector Economic Context 1 1.2 Project Formulation 2 1.3 Project Objectives and Scope at Appraisal 2 1.4 Financing Arrangements - Bank Group and others 3 2. EVALUATION 4 2.1 Evaluation Methodology and Approach 4 2.2 Performance Indicators 4 3. IMPLEMENTATION PERFORMANCE 5 3.1 Loan Effectiveness, Start-up and Implementation 5 3.2 Adherence to Project Costs, Disbursements & Financing Arrangements 6 3.3 Project Management, Reporting, Monitoring and Evaluation Achievements 6 4. PERFORMANCE EVALUATION AND RATINGS 7 4.1 Relevance of Objectives and Quality at Entry 7 4.2 Achievement of Objectives and Outputs. "Efficacy" 8 4.3 Efficiency 9 4.4 Institutional Development Impact 9 4.5 Sustainability 12 4.6 Aggregate Performance Rating 13 4.7 Performance of the Borrower 13 4.8 Bank Performance 13 4.9 Factors affecting Implementation Performance and Outcome 13 5. ECONOMIC INTEGRATION AND REGIONAL CO-OPERATION 14 5.1 Background 14 5.2 Regional Goals at Appraisal 14 5.3 Achievements 14 6. CONCLUSIONS, LESSONS LEARNT AND RECOMMENDATIONS 17 6.1 Conclusions 17 6.2 Lessons learnt 17 6.3 Recommendations 17 TABLES Table 1: Main Aggregates of the Transport and Communications Sector 1 Table 2: Sources of finances