World Bank Document

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Sister Brigid Gallagher Feast of St

.- The story of the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of )> Jesus and Mary in Zambia Brigid Gallagher { l (Bemba: to comfort, to cradle) The story of the Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary in Zambia 1956-2006 Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary Let us praise illustrious people, our ancestors in their successive generations ... whose good works have not been forgotten, and whose names live on for all generations. Book of Ecclesiasticus, 44:1, 1 First published in the United Kingdom in 2014 by Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary Text© 2014 Sisters of the Sacred Hearts of Jesus and Mary ISBN 978-0-99295480-2 Production, cover design and page layout by Nick Snode ([email protected]) Cover image by Michael Smith (dreamstime.com) Typeset in Palatino 12.5/14.Spt Printed and bound by www.printondemand-worldwide.com, Peterborough, UK Contents Foreword ................................... 5 To th.e reader ................................... 6 Mother Antonia ................................ 7 Chapter 1 Blazing the Trail .................... 9 Chapter 2 Preparing the Way ................. 19 Chapter 3 Making History .................... 24 Chapter4 Into Africa ......................... 32 Chapters 'Ladies in White' - Getting Started ... 42 Chapter6 Historic Events ..................... 47 Chapter 7 'A Greater Sacrifice' ................. 52 Bishop Adolph Furstenberg ..................... 55 Chapter 8 The Winds of Change ............... 62 Map of Zambia ................................ 68 Chapter 9 Eventful Years ..................... 69 Chapter 10 On the Edge of a New Era ........... 79 Chapter 11 'Energy and resourcefulness' ........ 88 Chapter 12 Exploring New Ways ............... 96 Chapter 13 Reading the Signs of the Times ...... 108 Chapter 14 Handing Over .................... 119 Chapter 15 Racing towards the Finish ......... -

Lot 1 - Km 4+100 to Km 86+770 Mpika to Shiwan’Gandu Junction (D53/T2 Junction) – 82.7 Km

REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA Road Development Agency Great North Road Rehabilitation (T2) – Mpika to Chinsali, Zambia Lot 1 - Km 4+100 to Km 86+770 Mpika to Shiwan’gandu Junction (D53/T2 Junction) – 82.7 km Financially supported by the European Investment Bank and The European Union BIDDING DOCUMENT Part 2: Employer’s Requirements Section VI Requirements [insert month and year] Bidding Document, Part 2 Section VI: Requirements VI-1 PART 2 – EMPLOYER’S REQUIREMENTS Section VI. Requirements This Section contains the Specification, the Drawings, and supplementary information that describe the Works to be procured. Bidding Document, Part 2 Section VI: Requirements VI-2 SCOPE OF WORKS The general items of work to be executed under this Contract include the following: (a) Establishment and, on completion of the Contract, removal of the Contractor's camp, plant, materials and personnel; (b) Establishment and, on completion of the Contract, removal of the Engineer's offices, laboratory and housing; (c) The provision of potable water supply for camps, offices, housing, and construction; (d) Confirmation and/or re-establishment of beacons and benchmarks as necessary as well as setting out of the Works; (e) Confirmation of the cross sections prepared at 20 metre intervals along the road in order that these can be used to enable the measurement of earthwork quantities by the Engineer for payment purposes; (f) The execution of all works as detailed in the Specifications and the Bills of Quantities and shown on the Drawings; (g) Accommodation of traffic; (h) -

Environmental Project Brief

Public Disclosure Authorized IMPROVED RURAL CONNECTIVITY Public Disclosure Authorized PROJECT (IRCP) REHABILITATION OF PRIMARY FEEDER ROADS IN EASTERN PROVINCE Public Disclosure Authorized ENVIRONMENTAL PROJECT BRIEF September 2020 SUBMITTED BY EASTCONSULT/DASAN CONSULT - JV Public Disclosure Authorized Improved Rural Connectivity Project Environmental Project Brief for the Rehabilitation of Primary Feeder Roads in Eastern Province Improved Rural Connectivity Project (IRCP) Rehabilitation of Primary Feeder Roads in Eastern Province EXECUTIVE SUMMARY The Government of the Republic Zambia (GRZ) is seeking to increase efficiency and effectiveness of the management and maintenance of the of the Primary Feeder Roads (PFR) network. This is further motivated by the recognition that the road network constitutes the single largest asset owned by the Government, and a less than optimal system of the management and maintenance of that asset generally results in huge losses for the national economy. In order to ensure management and maintenance of the PFR, the government is introducing the OPRC concept. The OPRC is a concept is a contracting approach in which the service provider is paid not for ‘inputs’ but rather for the results of the work executed under the contract i.e. the service provider’s performance under the contract. The initial phase of the project, supported by the World Bank will be implementing the Improved Rural Connectivity Project (IRCP) in some selected districts of Central, Eastern, Northern, Luapula, Southern and Muchinga Provinces. The project will be implemented in Eastern Province for a period of five (5) years from 2020 to 2025 using the Output and Performance Road Contract (OPRC) approach. GRZ thus intends to roll out the OPRC on the PFR Network covering a total of 14,333Kms country-wide. -

Agrarian Changes in the Nyimba District of Zambia

7 Agrarian changes in the Nyimba District of Zambia Davison J Gumbo, Kondwani Y Mumba, Moka M Kaliwile, Kaala B Moombe and Tiza I Mfuni Summary Over the past decade issues pertaining to land sharing/land sparing have gained some space in the debate on the study of land-use strategies and their associated impacts at landscape level. State and non-state actors have, through their interests and actions, triggered changes at the landscape level and this report is a synthesis of some of the main findings and contributions of a scoping study carried out in Zambia as part of CIFOR’s Agrarian Change Project. It focuses on findings in three villages located in the Nyimba District. The villages are located on a high (Chipembe) to low (Muzenje) agricultural land-use gradient. Nyimba District, which is located in the country’s agriculturally productive Eastern Province, was selected through a two-stage process, which also considered another district, Mpika, located in Zambia’s Muchinga Province. The aim was to find a landscape in Zambia that would provide much needed insights into how globally conceived land-use strategies (e.g. land-sharing/land-sparing trajectories) manifest locally, and how they interact with other change processes once they are embedded in local histories, culture, and political and market dynamics. Nyimba District, with its history of concentrated and rigorous policy support in terms of agricultural intensification over different epochs, presents Zambian smallholder farmers as victims and benefactors of policy pronouncements. This chapter shows Agrarian changes in the Nyimba District of Zambia • 235 the impact of such policies on the use of forests and other lands, with agriculture at the epicenter. -

12 Nts Wild Valleys Plains

12 nts Wild Valleys & Plains - Exclusive 12 nights / 13 days Starts Lusaka, Zambia / Ends Harare, Zimbabwe From $9860 USD per person P/Bag 0178, Maun, Botswana Tel: +267 72311321 [email protected] Botswana is our home Safaris are our passion Day Location Accommodation Transfers / Activities Meals 1 Arcades, Lusaka Lusaka Protea Hotel Upon arrival at Lusaka Airport – eta TBA – you - (bed and Standard room are met and road transfer to Lusaka Protea breakfast) Hotel. Settle into Hotel, afternoon at leisure. 2 South Luangwa Chinzombo Camp After breakfast, road transfer from Lusaka B, L (flight National Park Luxury Villa Protea Hotel to Lusaka airport for the Pro-flight time flight to Mfuwe Airport where you are met and permitting) road transfer to Chinzombo Camp. Afternoon , D & SB activity 3 South Luangwa Chinzombo Camp Day of activities: guided walking Safaris and B, L, D & SB National Park game drives into Luangwa national park 4 Luangwa River Mchenja Bush Camp After breakfast and possible morning activity B, L, D & SB Luxury safari tent game drive or walking transfer to Mchenja. Afternoon activity. 5 Luangwa River Mchenja Bush Camp Day of activities from a choice of: guided B, L, D & SB walking safaris, day and night game drives. 6 Lower Zambezi Chongwe River Camp After breakfast and possible morning activity B, L, D & SB Classic Safari Tent (flight time permitting), road transfer to Mfuwe airport for Pro Flight air transfer to Royal airstrip. Here you are met and transfer to Chongwe River camp. Afternoon activity 7 Lower Zambezi Chongwe River Camp Day of activities: game drives, guided walks, B, L, D & SB canoeing and boating 8 Mana Pools Ruckomenchi Camp After breakfast and possible morning activity, B, L, D & SB National Park Classic Safari Tent (flight time permitting) road/boat transfer across the border into Zimbabwe to Ruckomenchi Camp. -

USAID/Zambia Partners in Development Book

PARTNERS IN DEVELOPMENT July 2018 Partners in Zambia’s Development Handbook July 2018 United States Agency for International Development Embassy of the United States of America Subdivision 694 / Stand 100 Ibex Hill Road P.O. Box 320373 Lusaka, Zambia 10101 Cover Photo: As part of a private -sector and youth-engagement outreach partnership, media entrepreneur and UNAIDS Ambassador Lulu Haangala Wood (l), musician and entrepreneur Pompi (c), and Film and TV producer Yoweli Chungu (r) lend their voices to help draw attention to USAID development programs. (Photo Credit: Chando Mapoma / USAID Zambia) Our Mission On behalf of the American People, we promote and demonstrate democratic values abroad, and advance a free, peaceful, and prosperous world. In support of America's foreign policy, the U.S. Agency for International Development leads the U.S. Government's international development and disaster assistance through partnerships and investments that save lives, reduce poverty, strengthen democratic governance, and help people emerge from humanitarian crises and progress beyond assistance. Our Interagency Initiatives USAID/Zambia Partners In Development 1 The United States Agency for International Development (USAID) is the lead U.S. Government agency that works to end extreme global poverty and enable resilient, democratic societies to realize their potential. Currently active in over 100 countries worldwide, USAID was born out of a spirit of progress and innovation, reflecting American values and character, motivated by a fundamental belief in helping others. USAID provides development and humanitarian assistance in Africa, Asia and the Near East, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Europe. Headquartered in Washington, D.C., USAID retains field missions around the world. -

Can Design Thinking Be Used to Improve Healthcare in Lusaka Province, Zambia?

INTERNATIONAL DESIGN CONFERENCE - DESIGN 2014 Dubrovnik - Croatia, May 19 - 22, 2014. CAN DESIGN THINKING BE USED TO IMPROVE HEALTHCARE IN LUSAKA PROVINCE, ZAMBIA? C. A. Watkins, G. H. Loudon, S. Gill and J. E. Hall Keywords: ethnography, design thinking, Zambia, healthcare 1. Background ‘Africa experiences 24% of the global burden of disease, while having only 2% of the global physician supply and spending that is less than 1% of global expenditures.’ [Scheffler et al. 2008]. Every day the equivalent of two jumbo jets full of women die in Childbirth; 99% of these deaths occur in the developing world [WHO 2012]. For every death, 20 more women are left with debilitating conditions, such as obstetric fistula or other injuries to the vaginal tract [Jensen et al. 2008]. In the last 50 years, US$2.3 trillion has been spent on foreign aid [Easterly 2006]; US$1 trillion in Africa [Moyo 2009]. Despite this input, both Easterly and Moyo argue there has been little benefit. Easterly highlights that this enormous donation has not reduced childhood deaths from malaria by half, nor enabled poor families access to malaria nets at $4 each. Hodges [2007] reported that although equipment capable of saving lives is available in developing countries, more than 50% is not in service. Studies have asked why this should be so high [Gratrad et al. 2007], [Dyer et al. 2009], [Malkin et al. 2011] the majority focussing on medical equipment donation. They suggest that it is not feasible to directly donate equipment from high to low-income settings without understanding how the receiving environment differs from that which it is designed for. -

Africa's Freedom Railway

AFRICA HistORY Monson TRANSPOrtatiON How a Chinese JamiE MONSON is Professor of History at Africa’s “An extremely nuanced and Carleton College. She is editor of Women as On a hot afternoon in the Development Project textured history of negotiated in- Food Producers in Developing Countries and Freedom terests that includes international The Maji Maji War: National History and Local early 1970s, a historic Changed Lives and Memory. She is a past president of the Tanzania A masterful encounter took place near stakeholders, local actors, and— Studies Assocation. the town of Chimala in Livelihoods in Tanzania Railway importantly—early Chinese poli- cies of development assistance.” the southern highlands of history of the Africa —James McCann, Boston University Tanzania. A team of Chinese railway workers and their construction “Blessedly economical and Tanzanian counterparts came unpretentious . no one else and impact of face-to-face with a rival is capable of writing about this team of American-led road region with such nuance.” rail power in workers advancing across ’ —James Giblin, University of Iowa the same rural landscape. s Africa The Americans were building The TAZARA (Tanzania Zambia Railway Author- Freedom ity) or Freedom Railway stretches from Dar es a paved highway from Dar Salaam on the Tanzanian coast to the copper es Salaam to Zambia, in belt region of Zambia. The railway, built during direct competition with the the height of the Cold War, was intended to redirect the mineral wealth of the interior away Chinese railway project. The from routes through South Africa and Rhodesia. path of the railway and the After being rebuffed by Western donors, newly path of the roadway came independent Tanzania and Zambia accepted help from communist China to construct what would together at this point, and become one of Africa’s most vital transportation a tense standoff reportedly corridors. -

Remote River Rating in Zambia

Remote river rating in Zambia A case study in the Luangwa river basin a MSc study by Ivar Abas Remote river rating in Zambia A case study in the Luangwa river basin by I. Abas to obtain the degree of Master of Science at the Delft University of Technology, to be defended publicly on Friday December 21st, 2018. Student number: 4102088 Project duration: February 1st, 2018 – December 21st, 2018 Thesis committee: Prof. dr. ir. H.H.G. Savenije, TU Delft Ir. W.M.J. Luxemburg, TU Delft Dr. ir. H. Winsemius, Deltares & TU Delft Prof. dr. ir. M. Kok, TU Delft Ir. A. Couasnon, VU Amsterdam An electronic version of this thesis is available at http://repository.tudelft.nl/. "No man ever steps in the same river twice; for it’s not the same river and he’s not the same man." - HERACLITUS Acknowledgements This thesis would not have been a success without the help and resources of the Water Resources Manage- ment Center of the University of Zambia, therefore I want to express my gratitude. In particular I want to thank Professor Imasiku Nyambe for helping me out with all kinds of issues during my stay in Zambia and for his enthusiasm throughout the project. Besides the support of the University of Zambia I received a lot of help from the Zambian Water Resources Management Authority for which I express my deepest gratitude. I want to thank my thesis committee for guiding me the way and for the endless patients and enthusiasm I encountered when I bothered them with questions. -

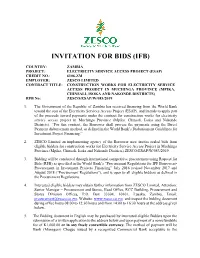

Invitation for Bids (Ifb)

INVITATION FOR BIDS (IFB) COUNTRY: ZAMBIA PROJECT: ELECTRICITY SERVICE ACCESS PROJECT (ESAP) CREDIT NO.: 6106-ZM EMPLOYER: ZESCO LIMITED CONTRACT TITLE: CONSTRUCTION WORKS FOR ELECTRICITY SERVICE ACCESS PROJECT IN MUCHINGA PROVINCE (MPIKA, CHINSALI, ISOKA AND NAKONDE DISTRICTS) RFB No: ZESCO/ESAP/W/083/2019 1. The Government of the Republic of Zambia has received financing from the World Bank toward the cost of the Electricity Services Access Project (ESAP), and intends to apply part of the proceeds toward payments under the contract for construction works for electricity service access project in Muchinga Province (Mpika, Chinsali, Isoka and Nakonde Districts). “For this contract, the Borrower shall process the payments using the Direct Payment disbursement method, as defined in the World Bank’s Disbursement Guidelines for Investment Project Financing.” 2. ZESCO Limited an implementing agency of the Borrower now invites sealed bids from eligible bidders for construction works for Electricity Service Access Project in Muchinga Province (Mpika, Chinsali, Isoka and Nakonde Districts) ZESCO/ESAP/W/083/2019. 3. Bidding will be conducted through international competitive procurement using Request for Bids (RFB) as specified in the World Bank’s “Procurement Regulations for IPF Borrowers- Procurement in Investment Projects Financing” July 2016 revised November 2017 and August 2018 (“Procurement Regulations”), and is open to all eligible bidders as defined in the Procurement Regulations. 4. Interested eligible bidders may obtain further information from ZESCO Limited, Attention: Senior Manager – Procurement and Stores, Head Office, RCC Building, Procurement and Stores Division Offices, P.O. Box 33304, 10101, Lusaka, Zambia, Email: [email protected], Website: www.zseco.co.zm and inspect the bidding document during office hours 08:00 to 12:30 hours and from 14:00 to 16:30 hours at the address given below. -

Annual Report of the Colonies, Northern Rhodesia, 1932

COLONIAL REPORTS—ANNUAL No. 1626 ANNUAL REPORT ON THE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC PROGRESS OF THE PEOPLE OF NORTHERN RHODESIA 1932 (For Reports for 1930 and 1031 see Nos. 1561 and respectively, price 2s. od. each) Crown Copyright Reserved LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY'S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H.M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.a; xao, George Street, Edinburgh t York Street, Manchester i; i, St. Andrew's Crescent, Cardiff 15, Donegall Square West, Belfast or through any Bookseller 1933 Price 2s. od. Net 58-1626 ANNUAL REPORT ON THE SOCIAL AND ECONOMIC PROGRESS OF THE PEOPLE OF NORTHERN RHODESIA, 1932 CONTENTS. Chapter Page> I,—GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE, AND HISTORY 2 II. —GOVERNMENT 6 III.—POPULATION ... ... ... 7 IV.—HEALTH 8 V.—HOUSING 10 VI.—PRODUCTION .. 12 VII.—COMMERCE 19 VIII.™WAGES AND COST OP LIVING 23 IX.—EDUCATION AND WELFARE INSTITUTIONS 25 X.—COMMUNICATIONS AND TRANSPORT 28 XI.—BANKING, CURRENCY, AND WEIGHTS AND MEASURES 31 XII.—PUBLIC WORKS ... ... 32 XIII.—JUSTICE, POLICE, AND PRISONS 34 XIV.—LEGISLATION 36 XV.—PUBLIC FINANCE AND TAXATION ... ... ... 41 APPENDIX 47 MAP I.—GEOGRAPHY, CLIMATE, AND HISTORY. Geography, The territory known as the Protectorate of Northern Rhodesia lies between longitudes 22° E. and 33° 33' E. and between latitudes 8° 15' S. and 18° S. It is bounded on the west by Angola, on the north-west by the Belgian Congo, on the north-east by Tanganyika Territory, on the east by the Nyasaland Protectorate and Portuguese East Africa, and on the south by Southern Rhodesia and the man dated territory of South-West Africa, comprising in all an area that is computed to be about 288,400 square miles. -

National Transportation System in the Republic of Zambia

World Maritime University The Maritime Commons: Digital Repository of the World Maritime University World Maritime University Dissertations Dissertations 1990 National transportation system in the Republic of Zambia Febby Mtonga WMU Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations Recommended Citation Mtonga, Febby, "National transportation system in the Republic of Zambia" (1990). World Maritime University Dissertations. 877. https://commons.wmu.se/all_dissertations/877 This Dissertation is brought to you courtesy of Maritime Commons. Open Access items may be downloaded for non- commercial, fair use academic purposes. No items may be hosted on another server or web site without express written permission from the World Maritime University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WMU LIBRARY WORLD MARITIME UNIVERSITY Malmo ~ Sweden THE NATIONAL TRANSPORTATION SYSTEM IN THE REPUBLIC OF ZAMBIA by Febby Mtonga Zambia A paper submitted to the faculty of the World Maritime University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of a MASTER OF SCIENCE DEGREE in GENERAL MARITIME ADMINISTRATION The views and contents expressed in this paper reflect entirely those of my own and are not to be construed as necessarily endorsed by the University Signed: Date : 0 5 I 11 j S O Assessed by: Professor J. Mlynarcz] World Maritime University Ilf Co-assessed by: U. 2).i TABLE OF CONTENTS 1 PREFACE i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ii ABBREVIATIONS ... LIST OF MAPS AND APPENDICES iv CHAPTER 1 M • O • o Profile of the Republic of Zambia 1 1.1.0 Geographical Location of Zambia 1.2.0 Population 1.3.0 The Economy 1.3.1 Mining 1.3.2 Agriculture 3 1.3.3 Manufacturing 4 1.3.4 Transportation 7 1.