Martin Kjellgren

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Yngve Brilioth Svensk Medeltidsforskare Och Internationell Kyrkoledare STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA LXXXV

SIM SWEDISH INSTITUTE OF MISSION RESEARCH PUBLISHER OF THE SERIES STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA & MISSIO PUBLISHER OF THE PERIODICAL SWEDISH MISSIOLOGICAL THEMES (SMT) This publication is made available online by Swedish Institute of Mission Research at Uppsala University. Uppsala University Library produces hundreds of publications yearly. They are all published online and many books are also in stock. Please, visit the web site at www.ub.uu.se/actashop Yngve Brilioth Svensk medeltidsforskare och internationell kyrkoledare STUDIA MISSIONALIA SVECANA LXXXV Carl F. Hallencreutz Yngve Brilioth Svensk medeltidsforskare och internationell kyrkoledare UTGIVENAV Katharina Hallencreutz UPPSALA 2002 Utgiven med forord av Katharina Hallencreutz Forsedd med engelsk sammanfattning av Bjorn Ryman Tryckt med bidrag fran Vilhelm Ekmans universitetsfond Kungl.Vitterhets Historie och Antivkvitetsakademien Samfundet Pro Fide et Christianismo "Yngve Brilioth i Uppsala domkyrkà', olja pa duk (245 x 171), utford 1952 av Eléna Michéew. Malningen ags av Stiftelsen for Âbo Akademi, placerad i Auditorium Teologicum. Foto: Ulrika Gragg ©Katharina Hallencreutz och Svenska lnstitutet for Missionsforskning ISSN 1404-9503 ISBN 91-85424-68-4 Cover design: Ord & Vetande, Uppsala Typesetting: Uppsala University, Editorial Office Printed in Sweden by Elanders Gotab, Stockholm 2002 Distributor: Svenska lnstitutet for Missionsforskning P.O. Box 1526,751 45 Uppsala Innehall Forkortningar . 9 Forord . 11 lnledning . 13 Tidigare Briliothforskning och min uppgift . 14 Mina forutsattningar . 17 Yngve Brilioths adressater . 18 Tillkommande material . 24 KAPITEL 1: Barndom och skolgang . 27 1 hjartat av Tjust. 27 Yngve Brilioths foraldrar. 28 Yngve Brilioths barndom och forsta skolar . 32 Fortsatt skolgang i Visby. 34 Den sextonarige Yngve Brilioths studentexamen. 36 KAPITEL 2: Student i Uppsala . -

Personal Agency at the Swedish Age of Greatness 1560–1720

Edited by Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen Marko and Karonen Petri by Edited Personal Agency at the Swedish Age of Greatness 1560-1720 provides fresh insights into the state-building process in Sweden. During this transitional period, many far-reaching administrative reforms were the Swedish at Agency Personal Age of Greatness 1560–1720 Greatness of Age carried out, and the Swedish state developed into a prime example of the ‘power-state’. Personal Agency In early modern studies, agency has long remained in the shadow of the study of structures and institutions. State building in Sweden at the Swedish Age of was a more diversified and personalized process than has previously been assumed. Numerous individuals were also important actors Greatness 1560–1720 in the process, and that development itself was not straightforward progression at the macro-level but was intertwined with lower-level Edited by actors. Petri Karonen and Marko Hakanen Editors of the anthology are Dr. Petri Karonen, Professor of Finnish history at the University of Jyväskylä and Dr. Marko Hakanen, Research Fellow of Finnish History at the University of Jyväskylä. studia fennica historica 23 isbn 978-952-222-882-6 93 9789522228826 www.finlit.fi/kirjat Studia Fennica studia fennica anthropologica ethnologica folkloristica historica linguistica litteraria Historica The Finnish Literature Society (SKS) was founded in 1831 and has, from the very beginning, engaged in publishing operations. It nowadays publishes literature in the fields of ethnology and folkloristics, linguistics, literary research and cultural history. The first volume of the Studia Fennica series appeared in 1933. Since 1992, the series has been divided into three thematic subseries: Ethnologica, Folkloristica and Linguistica. -

Fromcelebration Tocelebration

FromCelebration toCelebration Dress Code for Academic Events This guide introduces the dress code for academic events and festivities at Lappeenranta University of Technology. These festivities include the public defence of a dissertation, the post-doctoral karonkka banquet, and the conferment. Lappeenranta University of Technology was established in 1969 and, compared to many other universities, does not have long-standing traditions in academic festivities and especially doctoral conferment ceremonies. The following dress code should be observed at academic events at Lappeenranta University of Technology to establish in-house traditions. The instructions may, in some respects, differ from those of other universities. For instance with regard to colours worn by women, these instructions do not follow strict academic etiquette. 2 Contents Public Defence of a Dissertation 4 Conferment Ceremony 5 Dark Suit 6 Dark Suit, Accessories 8 Womens Semi-Formal Daytime Attire 10 White Tie 12 White Tie, Accessories 14 Womens Dark Suit, Doctoral Candidate 16 Womens Formal Daytime Attire, Doctor 18 Formal Evening Gown 20 Men's Informal Suit 22 Womens Informal Suit 24 Decorations 26 Doctoral Hat 28 Marshals 30 3 Public Defence of a Dissertation, Karonkka Banquet PUBLIC DEFENCE KARONKKA DOCTORAL CANDIDATE, White tie and tails, black vest White tie and tails, white vest if MALE (dark suit). ladies present (dark suit). Doctors: OPPONENT, doctoral hat. MALE CUSTOS, MALE p.12 p.12 DOCTORAL CANDIDATE, Womens dark suit, Formal evening gown, black. FEMALE high neckline, long sleeves, Doctors: doctoral hat. OPPONENT, suit with short skirt or trousers. FEMALE Opponent and custos: with CUSTOS, decorations. FEMALE p.16 p.20 CANDIDATES COMPANION, Semi-formal daytime attire, Formal evening gown, black. -

Erwin Panofsky

Reprinted from DE ARTIBUS OPUSCULA XL ESSAYS IN HONOR OF ERWIN PANOFSKY Edited l!J M I L LA RD M EIS S New York University Press • I90r Saint Bridget of Sweden As Represented in Illuminated Manuscripts CARL NORDENFALK When faced with the task of choosing an appropriate subject for a paper to be published in honor of Erwin Panofsky most contributors must have felt themselves confronted by an embarras de richesse. There are few main problems in the history of Western art, from the age of manuscripts to the age of movies, which have not received the benefit of Pan's learned, pointed, and playful pen. From this point of view, therefore, almost any subject would provide a suitable opportunity for building on foundations already laid by him to whom we all wish to pay homage. The task becomes at once more difficult if, in addition to this, more specific aims are to be considered. A Swede, for instance, wishing to see the art and culture of his own country play apart in this work, the association with which is itself an honor, would first of all have to ask himself if anything within his own national field of vision would have a meaning in this truly international context. From sight-seeing in the company of Erwin Panofsky during his memorable visit to Sweden in 1952 I recall some monuments and works of art in our country in which he took an enthusiastic interest and pleasure.' But considering them as illustrations for this volume, I have to realize that they are not of the international standard appropriate for such a concourse of contributors and readers from two continents. -

The Swedish Approach to Fairness

FACTS ABOUT SWEDEN | GENDER EQUALITY sweden.se PHOTO: MELKER DAHLSTRAND/IMAGEBANK.SWEDEN.SE PHOTO: The Swedish welfare system, which entitles both men and women to paid parental leave, has been central in promoting gender equality in Sweden. GENDER EQUALITY: THE SWEDISH APPROACH TO FAIRNESS Gender equality is one of the cornerstones of Swedish society. The aim of Sweden’s gender equality policies is to ensure that women and men enjoy the same opportunities, rights and obligations in all areas of life. The overarching principle is that every- areas of economics, politics, education school level onwards, with the aim of one, regardless of gender, has the right and health. Since the report’s inception, giving children the same opportunities to work and support themselves, to bal- Sweden has never finished lower than in life, regardless of their gender, by ance career and family life, and to live fourth in the Gender Gap rankings, which using teaching methods that counteract without the fear of abuse or violence. can be found at www.weforum.org. traditional gender patterns and gender Gender equality implies not only equal roles. distribution between men and women Gender equality at school Today, girls generally have better in all domains of society. It is also about Gender equality is strongly emphasised grades in Swedish schools than boys. the qualitative aspects, ensuring that in the Education Act, the law that gov- Girls also perform better in national the knowledge and experience of both erns all education in Sweden. It states tests, and a greater proportion of girls men and women are used to promote that gender equality should reach and complete upper secondary education. -

FULLTEXT01.Pdf

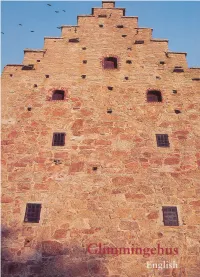

Digitalisering av redan tidigare utgivna vetenskapliga publikationer Dessa fotografier är offentliggjorda vilket innebär att vi använder oss av en undantagsregel i 23 och 49 a §§ lagen (1960:729) om upphovsrätt till litterära och konstnärliga verk (URL). Undantaget innebär att offentliggjorda fotografier får återges digitalt i anslutning till texten i en vetenskaplig framställning som inte framställs i förvärvssyfte. Undantaget gäller fotografier med både kända och okända upphovsmän. Bilderna märks med ©. Det är upp till var och en att beakta eventuella upphovsrätter. SWEDISH NATIONAL HERITAGE BOARD RIKSANTIKVARIEÄMBETET Cultural Monuments in S weden 7 Glimmingehus Anders Ödman National Heritage Board Back cover picture: Reconstruction of the Glimmingehus drawbridge with a narrow “night bridge” and a wide “day bridge”. The re construction is based on the timber details found when the drawbridge was discovered during the excavation of the moat. Drawing: Jan Antreski. Glimmingehus is No. 7 of a series entitled Svenska kulturminnen (“Cultural Monuments in Sweden”), a set of guides to some of the most interesting historic monuments in Sweden. A current list can be ordered from the National Heritage Board (Riksantikvarieämbetet) , Box 5405, SE- 114 84 Stockholm. Tel. 08-5191 8000. Author: Anders Ödman, curator of Lund University Historical Museum Translator: Alan Crozier Photographer: Rolf Salomonsson (colour), unless otherwise stated Drawings: Agneta Hildebrand, National Heritage Board, unless otherwise stated Editing and layout: Agneta Modig © Riksantikvarieämbetet 2000 1:1 ISBN 91-7209-183-5 Printer: Åbergs Tryckeri AB, Tomelilla 2000 View of the plain. Fortresses in Skåne In Skåne, or Scania as it is sometimes called circular ramparts which could hold large in English, there are roughly 150 sites with numbers of warriors, to protect the then a standing fortress or where legends and united Denmark against external enemies written sources say that there once was a and internal division. -

Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center

Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center Collection of Augustana Synod Letters MSS P:342 0.5 linear feet (1 box) Dates of collection: 1853–1908, 1914, 1927 Language: Swedish (bulk), English, Norwegian Access: The collection is open for research. A limited amount of photocopies may be requested via mail. Subject headings: Scandinavian Evangelical Lutheran Augustana Synod in North America Skandinaviska Evangelisk-Lutherska Augustana Synoden Swedish Evangelical Lutheran Augustana Synod in North America Evangelical Lutheran Augustana Synod in North America Augustana Theological Seminary (Rock Island, Ill.) Hasselquist, Tuve Nils, 1816-1891 Norelius, Eric, 1833-1916 Carlsson, Erland, 1822-1893 Lindahl, S. P. A. (Sven Peter August), 1843-1908 Esbjörn, Lars Paul, 1808-1870 Processed by: Rebecca Knapper, 2015 Related collections: Carlson, Erland papers, 1844-1893 Norelius, Eric, papers, 1851-1916 Repository: Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center Augustana College 639 38th Street Rock Island, IL 61201 309-794-7204 [email protected] Custodial History/Provenance Transferred to the Swenson Swedish Immigration Research Center from the Lutheran Church of America Archives in 1982. Biographical Sketch Collection of Augustana Synod Letters, 1853–1927 |Page 1 of 11 Documentation included with the transfer makes the following assumption about the collection: “Miscellaneous Letters (Possibly originally part of the Norelius Collection) Group I. 1848-1869 These letters are by a variety of persons addressed in turn to several persons not all of whom are definitely identifiable. They are all related, however, to the founding and early history of the Ev. Luth. Scandinavian (later Swedish) Augustana Synod (later Church). Thus they also relate clearly to early Swedish immigration to the Midwest. -

I. Paleografi, Boktryck Och Bokhistoria

I. Paleografi, boktryck och bokhistoria. 1. Paleografi, handskrifts- och urkundsväsen samt kronologi. 1. AHNLUND, N., Nils Rabenius (1648-1717). Studier i svensk historiografi. Stockh. 1927. 172 s., 1 pl. 8°. Om Nils Babenius' urkundsförfalskningar. Ree. 13. Boilmuus i SvT 1927, s. 295-298. - E. NOREEN i Korrespondens maj 1939, omtr. i förf:ns Från Birgitta till Piraten (1912), s. 84-89. 2. BECKMAN, BJ., Dödsdag och anniversarieda,_« i Norden med särskild hänsyn till Uppsalakalendariet 1344. KHÅ 1939, s. 112- 145. 3. BECKMAN, N., En förfalskning. ANF 1921/22, s. 216. Dipl. Svoc. I, s. 321. Ordet Abbutis i »Ogeri Abbatis» ändrat t. Rabbai (av Nils 11abenins). 4. Cod. Holm. B 59. ANF 57 (1943), s. 68-77. 5. BRONDUM-NIELSEN, J., Den nordiske Skrift. I: Haandbog i Bibl.-kundskab udg. af S. Dahl, Opl. 3, Bd 1 (1924), s. 51-90. 6. nom, G. T., Studies in scandinavian paleography 1-3. Journ. of engl. a. germ. philol., 14 (1913), s. 530-543; 16 (1915), s. 416-436. 7. FRANSEN, N., Svensk mässa präntad på, pergament. Graduale-kyriale (ordinarium missaa) på, svenska från 1500-talet. Sv. Tidskr. f. musikforskn. 9 (1927), s. 19-38. 8. GRANDINSON, K.-G., S:t Peters afton och andra date- ringar i Sveriges medeltidshandlingar. HT 1939, s. 52-59. 9. HAArANEN, T., Die Neumenfragmente der Universitäts- bibliothek Helsingfors. Eine Studie zur ältesten nordischen Musik- geschichte. Ak. avh. Hfors 1924. 114 s. 8°. ( - Helsingfors uni- versitetsbiblioteks skrifter 5.) Rec. C. F. HENNERBERG i NTBB 12 (1925), s. 45--49. 10. ---, Verzeichnis der mittelalterlichen Handschriften- fragmente in der Universitätsbibliothek zu Helsingfors I. -

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library

Verse and Transmutation History of Science and Medicine Library VOLUME 42 Medieval and Early Modern Science Editors J.M.M.H. Thijssen, Radboud University Nijmegen C.H. Lüthy, Radboud University Nijmegen Editorial Consultants Joël Biard, University of Tours Simo Knuuttila, University of Helsinki Jürgen Renn, Max-Planck-Institute for the History of Science Theo Verbeek, University of Utrecht VOLUME 21 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/hsml Verse and Transmutation A Corpus of Middle English Alchemical Poetry (Critical Editions and Studies) By Anke Timmermann LEIDEN • BOSTON 2013 On the cover: Oswald Croll, La Royalle Chymie (Lyons: Pierre Drobet, 1627). Title page (detail). Roy G. Neville Historical Chemical Library, Chemical Heritage Foundation. Photo by James R. Voelkel. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Timmermann, Anke. Verse and transmutation : a corpus of Middle English alchemical poetry (critical editions and studies) / by Anke Timmermann. pages cm. – (History of Science and Medicine Library ; Volume 42) (Medieval and Early Modern Science ; Volume 21) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback : acid-free paper) – ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) 1. Alchemy–Sources. 2. Manuscripts, English (Middle) I. Title. QD26.T63 2013 540.1'12–dc23 2013027820 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual “Brill” typeface. With over 5,100 characters covering Latin, IPA, Greek, and Cyrillic, this typeface is especially suitable for use in the humanities. For more information, please see www.brill.com/brill-typeface. ISSN 1872-0684 ISBN 978-90-04-25484-8 (hardback) ISBN 978-90-04-25483-1 (e-book) Copyright 2013 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands. -

The Saami Peoples from the Time of the Voyage of Ottar to Thomas Von Westen CHRISTIAN MERIOT*

ARCTIC VOL. 37, NO.l (DECEMBER 1984) P. 373-384 The Saami Peoples from the Time of the Voyage of Ottar to Thomas von Westen CHRISTIAN MERIOT* The history of the discovery and-understandingof the Saami THE SOURCES peoples can be divided into three periods. The-earliestrecord goes back to Tacitus, who in his Germania describes the Fenni The main sources of information follow, in chronological as savages, since they had neither weapons norhorses, dressed order. in animal skins, slept on the ground, and used bone weapon Ottar (Ohthere) was a rich- Norwegian landowner,.bailiff, tips for hunting because of their ignorance of iron. About A.D. and teacher during the reignof the Viking King Harald Haar- 150 Rolemy wrote of the Phinn0.i.Not until the De bello fager (Pairhair), at the end of the ninth century. In the course gothico of Prokopius, towards A.D. 550, were they called of a businessvisit to England, Ottar related to Alfredof “Skrithiphinoi”, an allusion to their ability to slide on wooden Wessex . (king from 87 1-901) the story of a voyage he had planks; in the De origine artihus Getarum of Jordanes, a con- made to.Helgeland, in the north of.his homeland. During this temporary of Prokopius, they are referred to as Screre,fennae voyage he rounded the Kola peninsula to Duna. King Alfred and Sirdfenni. This prehistory of the Sammi peoples can be included 0m’s.account in his translation of Orosius, towards said to end with theHistory of the Langobards by .Paulus Dia- 890. The Anglo-Samn.text, with an English translation, was conus (Varnefrid) about AD. -

THE DISCOVERY of the BALTIC the NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic C

THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC THE NORTHERN WORLD North Europe and the Baltic c. 400-1700 AD Peoples, Economies and Cultures EDITORS Barbara Crawford (St. Andrews) David Kirby (London) Jon-Vidar Sigurdsson (Oslo) Ingvild Øye (Bergen) Richard W. Unger (Vancouver) Przemyslaw Urbanczyk (Warsaw) VOLUME 15 THE DISCOVERY OF THE BALTIC The Reception of a Catholic World-System in the European North (AD 1075-1225) BY NILS BLOMKVIST BRILL LEIDEN • BOSTON 2005 On the cover: Knight sitting on a horse, chess piece from mid-13th century, found in Kalmar. SHM inv. nr 1304:1838:139. Neg. nr 345:29. Antikvarisk-topografiska arkivet, the National Heritage Board, Stockholm. Brill Academic Publishers has done its best to establish rights to use of the materials printed herein. Should any other party feel that its rights have been infringed we would be glad to take up contact with them. This book is printed on acid-free paper. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Blomkvist, Nils. The discovery of the Baltic : the reception of a Catholic world-system in the European north (AD 1075-1225) / by Nils Blomkvist. p. cm. — (The northern world, ISSN 1569-1462 ; v. 15) Includes bibliographical references (p.) and index. ISBN 90-04-14122-7 1. Catholic Church—Baltic Sea Region—History. 2. Church history—Middle Ages, 600-1500. 3. Baltic Sea Region—Church history. I. Title. II. Series. BX1612.B34B56 2004 282’485—dc22 2004054598 ISSN 1569–1462 ISBN 90 04 14122 7 © Copyright 2005 by Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, The Netherlands Koninklijke Brill NV incorporates the imprints Brill Academic Publishers, Martinus Nijhoff Publishers and VSP.