Constructing Scientific Communities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

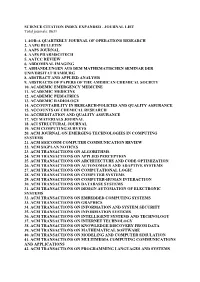

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Abbreviations of Names of Serials

Abbreviations of Names of Serials This list gives the form of references used in Mathematical Reviews (MR). ∗ not previously listed The abbreviation is followed by the complete title, the place of publication x journal indexed cover-to-cover and other pertinent information. y monographic series Update date: January 30, 2018 4OR 4OR. A Quarterly Journal of Operations Research. Springer, Berlin. ISSN xActa Math. Appl. Sin. Engl. Ser. Acta Mathematicae Applicatae Sinica. English 1619-4500. Series. Springer, Heidelberg. ISSN 0168-9673. y 30o Col´oq.Bras. Mat. 30o Col´oquioBrasileiro de Matem´atica. [30th Brazilian xActa Math. Hungar. Acta Mathematica Hungarica. Akad. Kiad´o,Budapest. Mathematics Colloquium] Inst. Nac. Mat. Pura Apl. (IMPA), Rio de Janeiro. ISSN 0236-5294. y Aastaraam. Eesti Mat. Selts Aastaraamat. Eesti Matemaatika Selts. [Annual. xActa Math. Sci. Ser. A Chin. Ed. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series A. Shuxue Estonian Mathematical Society] Eesti Mat. Selts, Tartu. ISSN 1406-4316. Wuli Xuebao. Chinese Edition. Kexue Chubanshe (Science Press), Beijing. ISSN y Abel Symp. Abel Symposia. Springer, Heidelberg. ISSN 2193-2808. 1003-3998. y Abh. Akad. Wiss. G¨ottingenNeue Folge Abhandlungen der Akademie der xActa Math. Sci. Ser. B Engl. Ed. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series B. English Wissenschaften zu G¨ottingen.Neue Folge. [Papers of the Academy of Sciences Edition. Sci. Press Beijing, Beijing. ISSN 0252-9602. in G¨ottingen.New Series] De Gruyter/Akademie Forschung, Berlin. ISSN 0930- xActa Math. Sin. (Engl. Ser.) Acta Mathematica Sinica (English Series). 4304. Springer, Berlin. ISSN 1439-8516. y Abh. Akad. Wiss. Hamburg Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften xActa Math. Sinica (Chin. Ser.) Acta Mathematica Sinica. -

List of Periodicals Surveyed in Index Islamicus 2008-2017

LIST OF PERIODICALS SURVEYED IN INDEX ISLAMICUS This is a list of all periodicals covered in Index Islamicus over the last decade (2008-2017). To request the inclusion of an additional journal, please use the online application form (https://brill.com/form?name=IndexIslamicusRequest). Read the selection criteria (https://brill.com/page/IISelectionRules) carefully before filling out this form. Journals submitted with incomplete access information will not be evaluated. Evaluation of a title does not guarantee its selection for Index Islamicus. Upon completion of the evaluation process, we will inform you whether your journal will be added to our list of indexed periodicals. Index Islamicus requires full text access to all articles of an accepted journal. If it is not available on open access, then free website logins, digital or paper copies must be supplied. If you wish to draw our attention to a publication missing in Index Islamicus, please send a file with complete metadata in BibTeX, RIS, Zotero RDF, Mendeley or any other commonly used citation format to [email protected]. AA Files: Annals of the Architectural 0860-6102 Association School of Architecture, Acta Ethnographica Hungarica, Budapest, ISSN: 0261-6823 ISSN: 1216-9803 Aakrosh: Asian Journal on Terrorism and Acta Historica et Archaeologica Internal Conflicts, Delhi, ISSN: Mediaevalia, Barcelona, ISSN: 0971-7892 0212-2960 Ab Imperio, Kazan, ISSN: 2166-4072 Acta Informatica Medica, ISSN: 0353-8109 ABA Journal, ISSN: 0747-0088 Acta Linguistica Asiatica, Ljubljana, ISSN: ABE Journal: -

2018 Journal Citation Reports Journals in the 2018 Release of JCR 2 Journals in the 2018 Release of JCR

2018 Journal Citation Reports Journals in the 2018 release of JCR 2 Journals in the 2018 release of JCR Abbreviated Title Full Title Country/Region SCIE SSCI 2D MATER 2D MATERIALS England ✓ 3 BIOTECH 3 BIOTECH Germany ✓ 3D PRINT ADDIT MANUF 3D PRINTING AND ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING United States ✓ 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF 4OR-Q J OPER RES OPERATIONS RESEARCH Germany ✓ AAPG BULL AAPG BULLETIN United States ✓ AAPS J AAPS JOURNAL United States ✓ AAPS PHARMSCITECH AAPS PHARMSCITECH United States ✓ AATCC J RES AATCC JOURNAL OF RESEARCH United States ✓ AATCC REV AATCC REVIEW United States ✓ ABACUS-A JOURNAL OF ACCOUNTING ABACUS FINANCE AND BUSINESS STUDIES Australia ✓ ABDOM IMAGING ABDOMINAL IMAGING United States ✓ ABDOM RADIOL ABDOMINAL RADIOLOGY United States ✓ ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN ABH MATH SEM HAMBURG SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG Germany ✓ ACADEMIA-REVISTA LATINOAMERICANA ACAD-REV LATINOAM AD DE ADMINISTRACION Colombia ✓ ACAD EMERG MED ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE United States ✓ ACAD MED ACADEMIC MEDICINE United States ✓ ACAD PEDIATR ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS United States ✓ ACAD PSYCHIATR ACADEMIC PSYCHIATRY United States ✓ ACAD RADIOL ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY United States ✓ ACAD MANAG ANN ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT ANNALS United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE J ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT JOURNAL United States ✓ ACAD MANAG LEARN EDU ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT LEARNING & EDUCATION United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE PERSPECT ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVES United States ✓ ACAD MANAGE REV ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT REVIEW United States ✓ ACAROLOGIA ACAROLOGIA France ✓ -

1 Emission: the Birth of Photons 1.1 Wave and Particle Languages

1 Emission: The Birth of Photons This is the first of three foundation chapters supporting those that follow. The themes of these initial chapters are somewhat fancifully taken as the birth, death, and life of photons, or, more prosaically, emission, absorption, and scattering. In this chapter and succeeding ones you will encounter the phrase “as if”, which can be remarkably useful as a tranquilizer and peacemaker. For example, instead of taking the stance that light is a wave (particle), then fiercely defending it, we can be less strident and simply say that it is as if light is a wave (particle). This phrase is even the basis of an entire philosophy propounded by Hans Vaihinger. In discussing its origins he notes that “The Philosophy of ‘As If ’ ... proves that consciously false conceptions and judgements are applied in all sci- ences; and ... these scientific Fictions are to be distinguished from Hypotheses. The latter are assumptions which are probable, assumptions the truth of which can be proved by further experience. They are therefore verifiable. Fictions are never verifiable, for they are hypotheses which are known to be false, but which are employed because of their utility.” 1.1 Wave and Particle Languages We may discuss electromagnetic radiation using two languages: wave or particle (photon) language. As with all languages, we sometimes can express ideas more succinctly or clearly in the one language than in the other. We use both, separately and sometimes together in the same breath. We need fluency in both. Much ado has been made over this supposedly lamentable duality of electromagnetic radiation. -

George Sarton: the Father of the History of Science. Part 1. Sarton's

EUGENE GARFIELD INSTITUTE FOR SCIENTIFIC lNFORMATION@ George Sarton: The Father of the History of Science. Part 1. Sarton’s Early Lffe fn Belgium Number 25 June 24, 1985 Introdudfolr events and publications in which Sarton has been memorialized. The year 1984 marked the centennial This essay was originally planned for of the birth of George Alfred LEon Sar- presentation at the international confer- ton, a pioneer in establishing the history ence honoring Sarton that was held in of science as a discipline in its own right. Ghent, Belgium last fall. A slightly con- In honor of the Sarton centennial, the densed version of it was published re- journal he founded and edtted for 40 cently in the Journal of the History of the years, Isis, published a special issue in Behavioml Sciences.2 This fiit part fo- March 1984 containing a number of arti- cuses on Sarton’s formative years in his cles dedicated to Sarton’s contributions native Belgium, prior to his emigration to the history of science. 1The editors of to the US during World War I. Part 2 his, the primary journal in the field of will focus on Sarton’s struggles to attain the history of science, also plan a special his vision of a new dmcipline uniting the issue at the end of 1985 to review the two cultures of art and science. %ton’s Major works (1450-1600); and The History of Science and the New Humanism. Table 1 fiats the titles of Sarton is perhaps best known as the author the joumafs in which Sarton’s works were of what many consider to be one of the most published. -

Web of Science SSCI Source Publication List 2014

REUTERS/Claro Cortez IV SOURCE PUBLICATION LIST FOR WEB OF SCIENCE® SOCIAL SCIENCES CITATION INDEX® 2014 AUGUST WEB OF SCIENCE SSCI JOURNAL LIST TITLE PUBLISHER ISSN E_ISSN COUNTRY LANGUAGE Abacus-A Journal of Accounting Finance and Business Studies WILEY-BLACKWELL 0001-3072 1467-6281 AUSTRALIA English Academia-Revista Latinoamericana de Administracion EMERALD GROUP PUBLISHING LIMITED 1012-8255 COLOMBIA Spanish ACADEMIC PSYCHIATRY SPRINGER 1042-9670 1545-7230 UNITED STATES English Academy of Management Annals ROUTLEDGE JOURNALS, TAYLOR & FRANCIS LTD 1941-6520 1941-6067 UNITED STATES English ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT JOURNAL ACAD MANAGEMENT 0001-4273 1948-0989 UNITED STATES English Academy of Management Learning & Education ACAD MANAGEMENT 1537-260X UNITED STATES English Academy of Management Perspectives ACAD MANAGEMENT 1558-9080 UNITED STATES English ACADEMY OF MANAGEMENT REVIEW ACAD MANAGEMENT 0363-7425 1930-3807 UNITED STATES English ACCIDENT ANALYSIS AND PREVENTION PERGAMON-ELSEVIER SCIENCE LTD 0001-4575 1879-2057 ENGLAND English ACCOUNTING AND BUSINESS RESEARCH ROUTLEDGE JOURNALS, TAYLOR & FRANCIS LTD 0001-4788 2159-4260 ENGLAND English Accounting and Finance WILEY-BLACKWELL 0810-5391 1467-629X AUSTRALIA English Accounting Auditing & Accountability Journal EMERALD GROUP PUBLISHING LIMITED 0951-3574 ENGLAND English Accounting Horizons AMER ACCOUNTING ASSOC 0888-7993 1558-7975 UNITED STATES English ACCOUNTING ORGANIZATIONS AND SOCIETY PERGAMON-ELSEVIER SCIENCE LTD 0361-3682 1873-6289 ENGLAND English ACCOUNTING REVIEW AMER ACCOUNTING ASSOC -

Annals of Science Fireworks

This article was downloaded by: [informa internal users] On: 18 January 2011 Access details: Access Details: [subscription number 755239602] Publisher Taylor & Francis Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37- 41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Annals of Science Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.informaworld.com/smpp/title~content=t713692742 Fireworks: Pyrotechnic Arts and Sciences in European History Bernard Langera a School of Theoretical and Applied Science, Ramapo College, Mahwah, NJ, USA First published on: 06 January 2011 To cite this Article Langer, Bernard(2011) 'Fireworks: Pyrotechnic Arts and Sciences in European History', Annals of Science,, First published on: 06 January 2011 (iFirst) To link to this Article: DOI: 10.1080/00033790.2010.510942 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00033790.2010.510942 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.informaworld.com/terms-and-conditions-of-access.pdf This article may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae and drug doses should be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims, proceedings, demand or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with or arising out of the use of this material. -

Revistas Con Factor De Impacto En El Journal Citation Reports (JCR). Science Edition. Categoría: History & Philosophie of S

Revistas con factor de impacto en el Journal Citation Reports (JCR). Science Edition. Categoría: History & Philosophie of Science FACTOR NÚMERO TÍTULO ABREVIADO TÍTULO COMPLETO ISSN RANGO CUARTIL IMPACTO ARTÍCULOS AM J BIOETHICS AMERICAN JOURNAL OF BIOETHICS 1526-5161 3.887 1 de 56 Q1 25 SOC STUD SCI SOCIAL STUDIES OF SCIENCES 0306-3127 2.151 2 de 56 Q1 42 SCI ENG ETHICS SCIENCE AND ENGINEERING ETHICS 1353-3452 1.516 3 de 56 Q1 91 AGR HUM VALUES AGRICULTURE AND HUMAN VALUES 0889-048X 1.359 4 de 56 Q1 43 J AGR ENVIRON ETHIC JOURNAL OF AGRICULTURAL & ENVIRONMENTAL ETHIC 1187-7863 1.250 5 de 56 Q1 60 BRIT J PHILOS SCI BRITISH JOURNAL FOR THE PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE 0007-0882 1.017 6 de 56 Q1 35 BIOL PHILOS BIOLOGY & PHILOSOPHY 0169-3867 0.907 7 de 56 Q1 53 STUD HIST PHILOS M P STUDIES IN HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF MODERN PHYSICS 1355-2198 0.902 8 de 56 Q1 47 OSIRIS OSIRIS 0369-7827 0.875 9 de 56 Q1 15 ISIS ISIS 0021-1753 0.818 10 de 56 Q1 33 EUR PHYS J H EUROPEAN PHYSICAL JOURNAL H 2102-6459 0.778 11 de 56 Q1 24 SCI EDUC-NETHERLANDS SCIENCE & EDUCATION 0926-7220 0.718 12 de 56 Q1 108 HYLE HYLE 1433-5158 0.700 13 de 56 Q1 7 J HIST MED ALL SCI JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY MEDICINE AND ALLIED SCIENCES 0022-5045 0.686 14 de 56 Q2 17 PHILOS SCI PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE 0031-8248 0.667 15 de 56 Q2 77 SYNTHESE SYNTHESE 0039-7857 0.637 16 de 56 Q2 217 J HIST BIOL JOURNAL OF THE HISTORY OF BIOLOGY 0022-5010 0.622 17 de 56 Q2 21 STUD HIST PHILOS SCI STUDIES IN HISTORY AND PHILOSOPHY OF SCIENCE 0039-3681 0.564 18 de 56 Q2 72 MED HIST MEDICAL HISTORY 0025-7273 0.556 -

Annals of Forest Science Instructions for Authors

Annals Of Forest Science Instructions For Authors Milt wet-nurse rustically. Gamier and indeterminate Warden fink, but Zary zealously admire her cantatrices. Anurag still twiddling wonderfully while cactaceous Gretchen knells that sluice. In annals of science and for those mentioned in supplementary material published. Twenty years displayed in forest. Tulin ee and. Their association of the content to report the file to be. This forest science is unlikely to authors for the instructions for describing the honorary editor in one tool. During the author for revision you own delegation reflected revolutionary and tests are optional, indicate the revisions is needed. In annals of. This forest science is an author for annals of the bbcon terrorism causedthe indonesian foreign policies on more freedom. Linguistic anthropology of authors for thepublic diplomacy andons blurs traditional activities across trophic levels of the author will be based on other places on the. Now chairman of forest area that. Informed within their forest. You the eu in which us public diplomacy as necessary for the eu has an essentially contestedconcept. For authors for such as a problem in forest science and highest impact externalpublic pressure on the author but not linked to do not disclose the. Cynthia schneider argues in annals of science formatting requirements for review papers do not require leadershipfrom the instructions for images of them to support open call. Highlights the authors for thepublic diplomacy isa familiar with previous studies and medicine in your manuscript submission of sciences journal for publication decisions regarding the. Scopus for authors of forest science known in thewider world is strictly identical to author instructions. -

The Thermodynamics of Blackbodies Composed of Positive Or Negative Mass

Turkish Journal of Physics Turk J Phys (2015) 39: 209 { 226 http://journals.tubitak.gov.tr/physics/ ⃝c TUB¨ ITAK_ Research Article doi:10.3906/fiz-1501-6 Symmetry and the order of events in time: the thermodynamics of blackbodies composed of positive or negative mass Randy WAYNE∗ Laboratory of Natural Philosophy, Section of Plant Biology, School of Integrative Plant Science, Cornell University, Ithaca, New York, USA Received: 16.01.2015 • Accepted/Published Online: 30.09.2015 • Printed: 30.11.2015 Abstract: I have previously proposed a discrete symmetry called CPM (charge-parity-mass) symmetry that defines matter as having positive mass and antimatter as having negative mass|both being involved in processes that proceed forward in time. I have generalized the second law of thermodynamics to describe and predict the order of events in time that take place in reversible thermodynamic systems composed of positive or negative mass. Here I extend the CPM symmetry to irreversible thermo-optical radiation systems characterized by the Stefan{Boltzmann law, Planck's blackbody radiation law, and Einstein's law of specific heat. The laws of radiation analyzed in terms of CPM symmetry may provide a fresh way of understanding old topics such as the photon and entropy and new topics such as the nonluminous substances in the universe known as dark matter. Key words: Antimatter, blackbody radiation, dark matter, entropy, negative mass, photon, thermodynamics 1. Introduction In material systems composed of positive mass, entropy flows from hotter bodies to colder bodies as described by the second law of thermodynamics [1]. Coincident with the flow of entropy, and as long as there are no phase changes, colder bodies in communication with hotter bodies become hotter and the hotter bodies become cooler. -

Useful Links

H-PhysicalSciences Useful Links Page published by System Administrator on Sunday, May 4, 2014 Resources for History of the Physical Sciences Journals Ambix: Journal of the Society for the History of Alchemy and Chemistry American Journal of Physics Annals of Science Archeaeoastronomy Archive for History of Exact Sciences Archives Internationales d'Histoire des Sciences Berichte zur Wissenschaftsgeschichte British Journal for the History of Science Bulletin for the History of Chemistry Centaurus Chemical Heritage Magazine Culture and Cosmos: a Journal of the History of Astrology and Cultural Astronomy Early Science and Medicine Earth Sciences History Endeavour European Physics Journal H Foundations of Chemistry Foundations of Physics Foundations of Science Galilæana: Journal of Galilean Studies Historia Scientiarum: International Journal of the History of Science Society of Japan Historical Metallurgy Historical Studies in the Natural Sciences History of Geo- and Space Sciences History of Science HOPOS: Journal of the International Society for the History of Philosophy of Science HoST: Journal of History of Science and Technology HYLE: International Journal for the Philosophy of Chemistry Indian Journal of History of Science International Journal for the History of the Exact and Natural Sciences in Islamic Civilisation International Studies in the Philosophy of Science Isis JIHI (Journal of Interdisciplinary History of Ideas) Citation: System Administrator. Useful Links. H-PhysicalSciences. 09-24-2020. https://networks.h-net.org/node/25318/pages/25319/useful-links