Annals of Science Fireworks

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

City of Bainbridge Island 2020 Lodging Tax / Tourism Fund Proposal Cover Sheet

CITY OF BAINBRIDGE ISLAND 2020 LODGING TAX / TOURISM FUND PROPOSAL COVER SHEET Project Name: 4th of July Fireworks Name of Applicant Organization: Bainbridge Island Lodging Association (BILA) Applicant Organization IRS Chapter Status and Tax ID Number: 501(c)3; EIN: 71-1051175 Date of Incorporation as a WA Corporation and UBI Number: January 16, 2002 / 602-175- 381 Primary Contact: Kelly Gurza and Scott Isenman Mailing Address: P.O. Box 10895, Bainbridge Island, Washington 98110 Email(s): [email protected] and [email protected] Cell phone: Kelly Gurza: 1 650 776-8306 Scott Isenman 1 206 661-6531 Project Type Tourism marketing Marketing and operations of special events and festivals designed to attract tourists. Supporting the operations of a tourism-related facility owned or operated by a nonprofit organization. Supporting the operations and/or capital expenditures of a tourism-related facility owned or operated by a municipality. LODGING/TOURISM FUND APPLICATION Applicant Information Please respond to each of these questions in the order listed. If the proposal includes multiple partners, please include the requested information for each organization. 1. Describe the applicant organization’s mission, history, and areas of expertise. Describe the applicant’s experience in tourism promotion on Bainbridge Island and its demonstrated ability to complete the proposed project. Alternate question for event or facility funding: Describe the event or facility proposed including its purpose, history, and budget. Include past attendance history, if applicable, and estimate the number of tourists drawn to the event or facility/year. Please estimate total attendance and the number of tourists estimated to attend for 2020. -

The Music Center Presents Downtown LA's Largest July 4Th

Contact: Bonnie Goodman FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE For Grand Park 213-308-9539 direct [email protected] The Music Center Presents Downtown LA’s Largest July 4th Celebration with Grand Park’s 4th of July Block Party – Free Blockbuster Event Will Light Up the Sky from the Rooftops Surrounding Grand Park – LOS ANGELES (June 3, 2015) – Angelenos will take over the civic center as they come together for an LA-style July 4th celebration at the third annual Grand Park’s 4th of July Block Party, presented by The Music Center. The free event, which runs from 3:00 p.m. – 9:30 p.m. on Saturday, July 4, 2015, will feature music, art, dancing, food, family, friends and fireworks for a feel-good, hometown event unlike any other Downtown LA has seen. Grand Park will light up the civic center skyline with a new, first-ever rooftop fireworks display set to iconic American music. The block party will be spread over eight city blocks, from Temple Street to 2nd Street, and from Grand Avenue to Main Street. Grand Park’s Fourth of July Block Party is supported by the County of Los Angeles, City Councilmember José Huizar, Bank of America and KCRW. During the block party, Grand Park’s green spaces will be transformed into giant picnic areas, while two dedicated stages – THE FRONT YARD on Grand Park’s Performance Lawn between Grand Avenue and Hill Street and THE BACKYARD on Grand Park’s Event Lawn between Broadway and Spring Street – will showcase a diverse lineup of LA-based musical artists, dancers, jump rope experts and spoken word artists. -

Article Hygroscopicity, Kappa (Κ), Alter Atmospheric Chemistry, and Cause Short-Term Adverse from 0.11 (Background) to 0.18 (fireworks)

Atmos. Chem. Phys., 21, 6155–6173, 2021 https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-21-6155-2021 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Measurement report: Firework impacts on air quality in Metro Manila, Philippines, during the 2019 New Year revelry Genevieve Rose Lorenzo1,2, Paola Angela Bañaga2,3, Maria Obiminda Cambaliza2,3, Melliza Templonuevo Cruz3,4, Mojtaba AzadiAghdam6, Avelino Arellano1, Grace Betito3, Rachel Braun6, Andrea F. Corral6, Hossein Dadashazar6, Eva-Lou Edwards6, Edwin Eloranta5, Robert Holz5, Gabrielle Leung2, Lin Ma6, Alexander B. MacDonald6, Jeffrey S. Reid7, James Bernard Simpas2,3, Connor Stahl6, Shane Marie Visaga2,3, and Armin Sorooshian1,6 1Department of Hydrology and Atmospheric Sciences, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, 85721, USA 2Manila Observatory, Quezon City, 1108, Philippines 3Department of Physics, School of Science and Engineering, Ateneo de Manila University, Quezon City, 1108, Philippines 4Institute of Environmental Science and Meteorology, University of the Philippines, Diliman, Quezon City, 1101, Philippines 5Space Science and Engineering Center, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, 53706, USA 6Department of Chemical and Environmental Engineering, University of Arizona, Tucson, Arizona, 85721, USA 7Marine Meteorology Division, Naval Research Laboratory, Monterey, CA, USA Correspondence: Armin Sorooshian ([email protected]) Received: 2 October 2020 – Discussion started: 4 November 2020 Revised: 15 February 2021 – Accepted: 19 -

The Use of Fireworks Inside of the City Limits Is Prohibited. However, On

The use of fireworks inside of the City - Place pets indoors; they are Limits is prohibited. However, on July 4th easily frightened by fireworks. What kinds of injuries occur? between the hours of 6:00pm and 11:00pm, - Always have water handy (a - Fireworks related injuries most residents may use Oregon legal consumer garden hose or bucket of water). frequently involve hands and fireworks, excluding City parks and the fingers: 29%, and eyes 20%. designated Urban / Wildand Interface. BE SAFE when lighting fireworks. - About half of the injuries are - An adult should always light burns, especially to the face, FIREWORKS ARE ILLEGAL AT ALL TIMES: fireworks. hand, wrist, or arm. 1. The area west of Highland Ave. and - Keep matches and lighters away Dimmick St., North of the railroad tracks from children. Which kinds of fireworks are the most 2. The area north of Interstate 5 - Use fireworks outdoors only. dangerous? 3. Panoramic Loop Area - Light one firework at a time. - Over 75% of fireworks injuries 4. Overland Drive Area - Keep children and pets away are from consumer fireworks like 5. Haviland Drive Area between Cloverlawn and Linden from fireworks. firecrackers, bottle rockets, 6. All City parks - Do not throw fireworks or hold Roman candles, fountains, and 7. Any area posted: in your hand. sparklers that are legal in many “NO FIREWORKS ALLOWED” states. BE RESPONSIBLE after lighting - Fireworks related injuries are fireworks. most commonly associated with ANNEXED AREAS - Soak used fireworks thoroughly firecrackers (51%), bottle rockets in a bucket of water. (12%) and sparklers (7%). Many properties have been annexed into the - Dispose of used fireworks and Grants Pass city limits over the years. -

Fireworks Application Wholesaler, Importer, And/Or Manufacturer

FIRE PROTECTION BUREAU - LICENSING SECTION PO Box 42600 Olympia WA 98504-2600 (360) 596-3946 FAX (360) 596-3934 E-Mail: [email protected] FIREWORKS APPLICATION WHOLESALER, IMPORTER, AND/OR MANUFACTURER INSTRUCTIONS This application can only be submitted during the month of January for the year you want to be licensed. Any applications received after January 31st will be returned and fees refunded. There are no exceptions. Complete the entire application. Please print in ink or type. Illegible or incomplete applications will be returned, which will delay the issuance of a license. Company Name Federal Tax Identification Number (FDID) Address: (Physical address - DO NOT use PO Box or Rural Route Numbers) Company Contact Person Mailing Address E-Mail Address for Contact Person Telephone Number Fax Number Company Web Site Address ( ) ( ) Applicant Doing Business As (type of business structure) – Check one and provide appropriate information for type. Individual - Provide the name of firm’s owner. Partnership - Provide name of each partner. Corporation - Provide the names of the corporate officers and their titles (president, vice president, and secretary). First Name Middle Initial Last Name Title Type of License Annual Description of License Applied For Fee A Wholesaler License is required when any person wants to engage in the Wholesaler selling of fireworks to a retailer or any other person for resale and any person $2,000 License who sells display fireworks to public display licensees. An Importer License is required when any person who, for any purpose other than personal use: Importer 1. Brings fireworks into this state or causes fireworks to be brought into this $1,000 License state; 2. -

Designing a Smart Helmet for Wildland Firefighters to Avoid Dehydration by Monitoring Bio-Signals

Designing a Smart Helmet for Wildland Firefighters to Avoid Dehydration by Monitoring Bio-signals Jiali Zhang He Feng Chee Jen Ngeh Global Innovation Exchange Global Innovation Exchange Global Innovation Exchange University of Washington University of Washington University of Washington Seattle, Washington, USA Seattle, Washington, USA Seattle, Washington, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] John Raiti Yuntao Wang Linda Wagner Global Innovation Exchange Global Innovation Exchange Global Innovation Exchange University of Washington Tsinghua University University of Washington Seattle, Washington, USA Beijing, China Seattle, Washington, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Paulo Goncalves Gulnara Sarymbekova Jenna James Global Innovation Exchange Global Innovation Exchange Vulcan Inc. University of Washington University of Washington Seattle, Washington, USA Seattle, Washington, USA Seattle, Washington, USA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Paul Albee Jay Thiagarajan Vulcan Inc. Vulcan Inc. Seattle, Washington, USA Seattle, Washington, USA [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT CCS CONCEPTS Smart Helmet is a new wearable device to monitor wildland fre- • Human-centered computing ! Interaction devices; • Hard- fghters’ real-time bio-signal data and alert potential health issues, ware ! Wireless devices. i.e., dehydration. In this paper, we applied the human-centered de- sign method to develop Smart Helmet for frefghters. We initially KEYWORDS conducted multiple rounds of primary research -

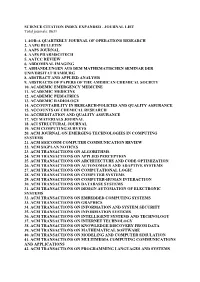

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total Journals: 8631

SCIENCE CITATION INDEX EXPANDED - JOURNAL LIST Total journals: 8631 1. 4OR-A QUARTERLY JOURNAL OF OPERATIONS RESEARCH 2. AAPG BULLETIN 3. AAPS JOURNAL 4. AAPS PHARMSCITECH 5. AATCC REVIEW 6. ABDOMINAL IMAGING 7. ABHANDLUNGEN AUS DEM MATHEMATISCHEN SEMINAR DER UNIVERSITAT HAMBURG 8. ABSTRACT AND APPLIED ANALYSIS 9. ABSTRACTS OF PAPERS OF THE AMERICAN CHEMICAL SOCIETY 10. ACADEMIC EMERGENCY MEDICINE 11. ACADEMIC MEDICINE 12. ACADEMIC PEDIATRICS 13. ACADEMIC RADIOLOGY 14. ACCOUNTABILITY IN RESEARCH-POLICIES AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 15. ACCOUNTS OF CHEMICAL RESEARCH 16. ACCREDITATION AND QUALITY ASSURANCE 17. ACI MATERIALS JOURNAL 18. ACI STRUCTURAL JOURNAL 19. ACM COMPUTING SURVEYS 20. ACM JOURNAL ON EMERGING TECHNOLOGIES IN COMPUTING SYSTEMS 21. ACM SIGCOMM COMPUTER COMMUNICATION REVIEW 22. ACM SIGPLAN NOTICES 23. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ALGORITHMS 24. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON APPLIED PERCEPTION 25. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON ARCHITECTURE AND CODE OPTIMIZATION 26. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON AUTONOMOUS AND ADAPTIVE SYSTEMS 27. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTATIONAL LOGIC 28. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER SYSTEMS 29. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON COMPUTER-HUMAN INTERACTION 30. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DATABASE SYSTEMS 31. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON DESIGN AUTOMATION OF ELECTRONIC SYSTEMS 32. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON EMBEDDED COMPUTING SYSTEMS 33. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON GRAPHICS 34. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION AND SYSTEM SECURITY 35. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INFORMATION SYSTEMS 36. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTELLIGENT SYSTEMS AND TECHNOLOGY 37. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON INTERNET TECHNOLOGY 38. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON KNOWLEDGE DISCOVERY FROM DATA 39. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MATHEMATICAL SOFTWARE 40. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MODELING AND COMPUTER SIMULATION 41. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON MULTIMEDIA COMPUTING COMMUNICATIONS AND APPLICATIONS 42. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON PROGRAMMING LANGUAGES AND SYSTEMS 43. ACM TRANSACTIONS ON RECONFIGURABLE TECHNOLOGY AND SYSTEMS 44. -

Department of Business, Economic Development

DAVID Y. IGE GOVERNOR MIKE MCCARTNEY DEPARTMENT OF BUSINESS, DIRECTOR ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT & TOURISM No. 1 Capitol District Building, 250 South Hotel Street, 5th Floor, Honolulu, Hawaii 96813 Telephone: (808) 586-2355 Mailing Address: P.O. Box 2359, Honolulu, Hawaii 96804 Fax: (808) 586-2377 Web site: www.hawaii.gov/dbedt Statement of MIKE MCCARTNEY Director Department of Business, Economic Development, and Tourism before the SENATE COMMITTEES ON PUBLIC SAFETY, INTERGOVERNMENTAL, AND MILITARY AFFAIRS AND ENERGY, ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT, AND TOURISM Wednesday, February 6, 2019 2:45 PM State Capitol, Conference Room 414 In consideration of SB 154 RELATING TO FIREWORKS. Chairs Nishihara and Wakai, Vice Chairs Wakai and Taniguchi, and members of the Committee. The Department of Business, Economic Development and Tourism (DBEDT) supports SB154 which authorizes the use of fireworks for film and theatrical productions and for testing, disposal, and destruction of illegal or unwanted fireworks by law enforcement. This bill would allow film productions to use consumer fireworks, aerial devices, display fireworks or articles pyrotechnics during a special effects scene in a safe and monitored environment by allowing film productions an exemption to the General Prohibitions in §132D-5. The film industry often utilizes pyrotechnics as part of special effects and stunts. When Legendary Entertainment filmed Godzilla vs. Kong and Universal Pictures produced Jurassic World: Fallen Kingdom in Hawaii - pyrotechnics was an essential part of the making of both films. The ongoing TV Series Hawaii 5-0 and Magnum P.I. often use pyrotechnics – creating an exciting array of action packed story telling. These and other productions do these operations precisely and carefully to ensure the safety of the public, crew and cast. -

Fireworks on the Island Press Release

Media Contact: Teresa Rodriguez Senior Marketing & Communications Manager Telephone: (956) 761-8199 E-mail: [email protected] FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE South Padre Island kicks off the summer season with family-friendly fireworks displays South Padre Island, Wednesday, June 16, 2021- The City of South Padre Island, is kicking off the summer season with beach and bayside fireworks displays running through Labor Day. South Padre Island, also known as “The Fireworks Capital of Texas,” an honor proclaimed by the Texas Senate, the Island’s recognition highlights the abundance of spectacular fireworks displays for visiting individuals, couples, and families to enjoy. It is time to celebrate the season with beach and bayside fireworks on South Padre Island. On Tuesday evenings, fireworks are shot from a barge anchored a few hundred yards off shore in the bay. The best viewing spot for bayside shows is the Entertainment District, including many bayside restaurants and on “The Green,” a great lawn where people can bring their own chairs to view the display. "Fireworks over the water are amazing," said Ed Caum, South Padre Island CVB Director, "you get to see the beautiful bursts in the sky and they are reflected back up from the water”. This also allows you to view them from both the shore and on a boat.” Many of the local boat captains and tour companies book specific cruises to enjoy the fireworks from out on the water. “If you have never viewed fireworks from out on the water, you need to experience it," Caum said. For beachside firework displays, the Island features shows every Thursday, Friday and Saturday evenings. -

Building a Music Rhythm Video Game Information Systems and Computer

Building a music rhythm video game Ruben Rodrigues Rebelo Thesis to obtain the Master of Science Degree in Information Systems and Computer Engineering Supervisor: Prof. Rui Filipe Fernandes Prada Examination Committee Chairperson: Nuno Joao˜ Neves Mamede Supervisor: Prof. Rui Filipe Fernandes Prada Member of the Committee: Carlos Antonio´ Roque Martinho November 2016 Acknowledgments I would like to thank my supervisor, Prof. Rui Prada for the support and for making believe that my work in this thesis was not only possible, but also making me view that this work was important for myself. Also I want to thank Carla Boura Costa for helping me through this difficult stage and clarify my doubts that I was encountered this year. For the friends that I made this last year. Thank you to Miguel Faria, Tiago Santos, Nuno Xu, Bruno Henriques, Diogo Rato, Joana Condec¸o, Ana Salta, Andre´ Pires and Miguel Pires for being my friends and have the most interesting conversations (and sometimes funny too) that I haven’t heard in years. And a thank you to Vaniaˆ Mendonc¸a for reading my dissertation and suggest improvements. To my first friends that I made when I entered IST-Taguspark, thank you to Elvio´ Abreu, Fabio´ Alves and David Silva for your support. A small thank you to Prof. Lu´ısa Coheur for letting me and my origamis fill some of the space in the room of her students. A special thanks for Inesˆ Fernandes for inspire me to have the idea for the game of the thesis, and for giving special ideas that I wish to implement in a final version of the game. -

C:\Documents and Settings\Philu\Local Settings\Temp

Provo City Land Use Codes LIVING AREAS 1000 This major category applies to structures on the land and corresponding area used primarily as places to live whether on a temporary (e.g. transient lodging, hotel), semi-permanent (e.g. hotel, fraternity, sorority) or permanent (e.g. home or apartment) basis. This category may also include structures on parcels and corresponding area that are used for two or more activities yet the dominant use of the structure is for living purposes. An example of dual use of a structure where living is secondary might be a convalescent home. Since medical service is the primary use of the property, convalescent home is coded under Services 6516. The Household Units section has been developed to reflect certain structure characteristics as well as activity. For example, a code category and respective number is given to represent household units in terms of arrangement with respect to each other and to non-residential structures. Diagrams of these special conditions are provided to represent the meaning of respective code categories. 1100 HOUSEHOLD UNITS 1110 Single Family Dwelling 1111 Single family dwelling, detached (with or without an attached garage, on one parcel. Includes cabins, non-commercial) 1112 Single family dwelling, attached (to one or more single family dwelling) 1113 Single family dwelling, attached (to a commercial, industrial or other nonresidential use. Dwelling unit can be under, over, in front, behind or beside non residential use in the structure.) NOTE: If a single family dwelling is on the same parcel with a nonresidential use, and is not attached, subparcel and code use each separately. -

Abbreviations of Names of Serials

Abbreviations of Names of Serials This list gives the form of references used in Mathematical Reviews (MR). ∗ not previously listed The abbreviation is followed by the complete title, the place of publication x journal indexed cover-to-cover and other pertinent information. y monographic series Update date: January 30, 2018 4OR 4OR. A Quarterly Journal of Operations Research. Springer, Berlin. ISSN xActa Math. Appl. Sin. Engl. Ser. Acta Mathematicae Applicatae Sinica. English 1619-4500. Series. Springer, Heidelberg. ISSN 0168-9673. y 30o Col´oq.Bras. Mat. 30o Col´oquioBrasileiro de Matem´atica. [30th Brazilian xActa Math. Hungar. Acta Mathematica Hungarica. Akad. Kiad´o,Budapest. Mathematics Colloquium] Inst. Nac. Mat. Pura Apl. (IMPA), Rio de Janeiro. ISSN 0236-5294. y Aastaraam. Eesti Mat. Selts Aastaraamat. Eesti Matemaatika Selts. [Annual. xActa Math. Sci. Ser. A Chin. Ed. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series A. Shuxue Estonian Mathematical Society] Eesti Mat. Selts, Tartu. ISSN 1406-4316. Wuli Xuebao. Chinese Edition. Kexue Chubanshe (Science Press), Beijing. ISSN y Abel Symp. Abel Symposia. Springer, Heidelberg. ISSN 2193-2808. 1003-3998. y Abh. Akad. Wiss. G¨ottingenNeue Folge Abhandlungen der Akademie der xActa Math. Sci. Ser. B Engl. Ed. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series B. English Wissenschaften zu G¨ottingen.Neue Folge. [Papers of the Academy of Sciences Edition. Sci. Press Beijing, Beijing. ISSN 0252-9602. in G¨ottingen.New Series] De Gruyter/Akademie Forschung, Berlin. ISSN 0930- xActa Math. Sin. (Engl. Ser.) Acta Mathematica Sinica (English Series). 4304. Springer, Berlin. ISSN 1439-8516. y Abh. Akad. Wiss. Hamburg Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften xActa Math. Sinica (Chin. Ser.) Acta Mathematica Sinica.