Wabamun Lake Subwatershed Land Use Plan Phase 1 Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jackfish Lake State of the Watershed Report

Jackfish Lake State of the Watershed Report April 2016 North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance 202 - 9440 49th St NW Edmonton, AB T6B 2M9 Tel: (587) 525-6820 Email: [email protected] http://www.nswa.ab.ca The North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance (NSWA) is a non-profit society whose purpose is to protect and improve water quality and ecosystem functioning in the North Saskatchewan River watershed in Alberta. The organization is guided by a Board of Directors composed of member organizations from within the watershed. It is the designated Watershed Planning and Advisory Council (WPAC) for the North Saskatchewan River under the Government of Alberta’s Water for Life Strategy.. This report was prepared by Jennifer Regier, B.Sc. and David Trew, P.Biol of the North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance. Cover photo credit: Dara Choy, Stony Plain AB Suggested Citation: North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance (NSWA). 2016. Jackfish Lake State of the Watershed Report. Prepared by the NSWA, Edmonton, AB. for the Jackfish Lake Management Association, Carvel, AB. Available on the internet at http://www.nswa.ab.ca/resources/ nswa_publications Jackfish Lake State of the Watershed Report Executive Summary The purpose of this report is to consolidate environmental information on Jackfish Lake and its watershed in an effort to support future planning and management discussions. The report provides perspective on current environmental conditions at the lake relative to regional and historic trends. The report is provided as advice to the Jackfish Lake Management Association (JLMA), Alberta Environment and Parks, and Parkland County. The technical information contained in this document is detailed and addresses many lake and watershed features. -

Wabamun Lake Water Quality 1982 to 2001

WABAMUN LAKE WATER QUALITY 1982 TO 2001 WABAMUN LAKE WATER QUALITY 1982 TO 2001 Prepared by: Richard Casey, M.Sc. Limnologist Science and Standards Alberta Environment September 2003 W0309 Pub. No: T/695 ISBN: 0-7785-2503-1 (Printed Edition) ISBN: 0-7785-2504-X (On-Line Edition) Web Site: http://www3.gov.ab.ca/env/info/infocentre/publist.cfm Any comments, questions, or suggestions regarding the content of this document may be directed to: Environmental Monitoring and Evaluation Branch Alberta Environment 10th Floor, Oxbridge Place 9820 – 106th Street Edmonton, Alberta T5K 2J6 Phone: (780) 427-6278 Fax: (780) 422-6712 Additional copies of this document may be obtained by contacting: Information Centre Alberta Environment Main Floor, Great West Life Building 9920 – 108th Street Edmonton, Alberta T5K 2M4 Phone: (780) 944-0313 Fax: (780) 427-4407 Email: [email protected] SUMMARY Wabamun Lake, approximately 60 km west of Edmonton, is large, shallow, and generally well mixed. Sport fish in the lake include northern pike, yellow perch, and lake whitefish. There are a unique mix of land uses in the lake watershed, which include undisturbed bush and forest, agriculture, two coal mines with active and reclaimed areas, three coal-fired power plants, major transportation (road and rail) corridors, residences, and recreation. The mines supply fuel for the power plants, operated by the TransAlta Utilities Corporation (TAU). Industrial wastewaters, runoff and cooling water from the Whitewood mine and Wabamun power plant are discharged to the lake. Over time, TAU operations associated with the mines and power plants in the watershed have caused cumulative and ongoing impacts on the lake level. -

Lake-Sediment Record of PAH, Mercury, and Fly-Ash Particle Deposition Near Coal-Fired Power Plants in Central Alberta, Canada

Lake-sediment record of PAH, mercury, and fly-ash particle deposition near coal-fired power plants in Central Alberta, Canada Benjamin D. Barsta,†, Jason M.E. Ahadb*, Neil L. Rosec, Josué J. Jautzyd, Paul E. Drevnicke, Paul Gammonf, Hamed Saneig, and Martine M. Savardb aINRS-ETE, Université du Québec, 490 de la Couronne, Québec, QC, G1K 9A9, Canada bGeological Survey of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, 490 de la Couronne, Québec, QC, G1K 9A9, Canada cEnvironmental Change Research Centre, Department of Geography, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK dUniversity of Ottawa, Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences, 25 Templeton St., Ottawa, ON, K1N 6N5, Canada. eEnvironmental Monitoring and Science Division, Alberta Environment and Parks, Calgary, AB T2E 7L7, Canada fGeological Survey of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, 601 Booth Street, Ottawa, ON, K1A 0E8, Canada gGeological Survey of Canada, Natural Resources Canada, 3303-33rd Street N.W., Calgary, AB, T2L 2A7, Canada †Current address: Faculty of Agricultural and Environmental Sciences, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada *Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 1 We report a historical record of atmospheric deposition in dated sediment cores from Hasse 2 Lake, ideally located near both currently and previously operational coal-fired power plants in 3 Central Alberta, Canada. Accumulation rates of spheroidal carbonaceous particles (SCPs), an 4 unambiguous marker of high-temperature fossil-fuel combustion, in the early part of the sediment 5 record (pre-1955) compared well with historical emissions from one of North America’s earliest 6 coal-fired power plants (Rossdale) located ~43 km to the east in the city of Edmonton. -

Ca 1978 ISSS Tours 8+16E Report.Pdf

11th CONGRESS I NT ERNA TI ONAL I OF SOIL SCIENCE EDMONTON, CANADA JUNE 1978 GUIDEBOOK FOR A SOILS LAND USE TOUR IN BANFF AND JASPER NATIONAL PARKS TOURS 8 AND 16 L.J. KNAPIK Soils Division, Al Research Council, Edmonton G.M. COEN Research Branch, culture Canada, Edmonton Alberta Research Council Contribution Series 809 ture Canada Soil Research Institute tribution 654 Guidebook itors D.F. Acton and L.S. Crosson Saskatchewan Institute of Pedology Saskatoon, Saskatchewan ~-"-J'~',r--- --\' "' ~\>(\ '<:-q, ,v ~ *'I> co'"' ~ (/) ~ AlBERTA \._____ ) / ~or th '(<.\ ~ e r ...... e1Bowden QJ' - Q"' Olds• Y.T. I N.W.T. _...,_.. ' h./? 1 ...._~ ~ll"O"W I ,-,- B.C. / U.S.A. ' '-----"'/' FIG. 1 GENERAL ROUTE MAP i; i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...............•..................................... vi INTRODUCTION ........................................................ 1 GENERAL ITINERARY ................................................... 2 REGIONAL OVERVIEW ..•................................................. 6 The Alberta Plain .................................................. 6 15 The Rocky Mountain Foothills ........................................ The Rocky Mountains ................................................ 17 DAY 1: EDMONTON TO BANFF . • . 27 Road Log No. 1: Edmonton to Calgary.......................... 27 The Lacombe Research Station................................. 32 Road Log No. 2: Calgary to Banff............................ 38 Kananaskis Site: Orthic Eutric Brunisol.... .. ...... ... ....... 41 DAY 2: BANFF AND -

North Saskatchewan Regional Plan: Lake Paleolimnology Survey Final Report

Contract Name: NSRP Lake Paleolimnology Survey Consultant Name: Hutchinson Environmental Sciences Ltd. This report was commissioned by Alberta Environment and Sustainable Resource Development (now Alberta Environment and Parks) to support both the implementation of the Land-Use Framework and the Cumulative Effects Management System. Recreational lakes within the North Saskatchewan Regional plan boundaries are of high ecological and recreational value. To better understand how to effectively manage cumulative impacts on the lakes, it is necessary to understand conditions in the lakes prior to development. Knowing these pre-development conditions will assist in setting reasonable and achievable goals for lake management. The paleolimnology study was undertaken by Hutchinson Environmental Sciences Ltd. The objective of the study was to provide a paleolimnological reconstruction of water quality conditions at Pigeon and Wabamun lakes. Sediment cores were collected, sectioned, and analyzed to assess temporal variability in paleolimnological indicators. Based on these results, an overview of anthropogenic impacts on lake water quality was to be provided. Both Wabamun and Pigeon lakes are productive, alkaline, and polymictic, and are situated within a carbonaceous geological setting. These characteristics are known to influence the interpretation of results and were not sufficiently considered in the report. Future work may be required to further describe the limitations and evaluate the data presented in report. This report has been completed in accordance with the contract issued by Alberta Environment and Parks (AEP). AEP has closed this project and considers this report final. AEP does not necessarily endorse all of the contents of this report, nor does the report necessarily represent the views or opinions of AEP or stakeholders. -

Highvale End Land Use Area Structure Plan

PARKLAND COUNTY BYLAW 2016-12 BEING A BYLAW OF PARKLAND COUNTY FOR THE PURPOSES OF ADOPTING A NEW HIGHVALE END LAND USE AREA STRUCTURE PLAN WHEREAS Section 633 (1) of the Municipal Government Act, R.S.A.2000, Chapter M-26 and amendments thereto authorize a council to adopt an Area Structure Plan for the purpose of providing a framework for subsequent subdivision and development of an area of land within a municipality; and WHEREAS the Council of Parkland County deems it appropriate and desirable to adopt a new Area Structure Plan for the Highvale area; and WHEREAS the Highvale End Land Use Area Structure Plan Bylaw 28-97, and amending Bylaws 40-2006 and 201 4-25 are no longer required; NOW THEREFORE the Council of Parkland County duly assembled and under the authority of the Municipal Government Act, as amended, hereby enacts the following: 1. That the "Highvale End Land Use Area Structure Plan" attached hereto and forming part of this bylaw, is herebyadopted. 2. That the Highvale End Land Use Area Structure Plan Bylaw 28-97, and amending Bylaws40-2006 and 2014-25 are hereby rescinded. AND THAT this bylaw shall come into force and effect from third and final reading and signing thereof. READ A FIRST TIME this 1't day of May, 2016 PUBLIC HEARING held this 12th day of July, 2016 and this 27th day of September,2016. READ A SECOND TIME this 27th day of September,2016. READ A THIRD TIME AND FINAL TIME this 27th day of September,2016. r Chief Administr Officer Highvale End Land Use Area Structure Plan September 2016 Highvale End Land Use Area -

Mayatan Lake State of the Watershed Report

Mayatan Lake State of the Watershed Report August 2012 Mayatan Lake State of the Watershed Report North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance 9504‐49 Street Edmonton, AB T6B 2M9 Tel: (780) 442‐6363 Fax: (780) 495‐0610 Email: [email protected] http://www.nswa.ab.ca The North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance (NSWA) is a non‐profit society whose purpose is to protect and improve water quality and ecosystem functioning in the North Saskatchewan River watershed in Alberta. The organization is guided by a Board of Directors composed of member organizations from within the watershed. It is the designated Watershed Planning and Advisory Council (WPAC) for the North Saskatchewan River under the Government of Alberta’s Water for Life Strategy. This report was prepared by Melissa Logan, P.Biol., Billie Milholland, B.A., and David Trew, P.Biol., of the North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance. Suggested Citation: North Saskatchewan Watershed Alliance (NSWA). 2012. Mayatan Lake State of the Watershed Report. Prepared by the NSWA, Edmonton, AB., for the Mayatan Lake Management Association, Carvel, AB. Available on the internet at http://www.nswa.ab.ca/resources/nswa_publications 1 Mayatan Lake State of the Watershed Report Acknowledgements The NSWA gratefully acknowledges the contribution of the following persons towards the completion of this report: Yaw Okyere and Janet Yan of Alberta Environment for conducting a search of water allocations within the basin; Terry Chamuluk of Alberta Environment for providing Morton monthly evaporation estimates for Alberta; Ron Woodvine of AAFC for providing precipitation and evaporation tables and maps for the Canadian Prairies; Rick Rickwood and Candace Vanin of AAFC for providing maps and delineating the gross and effective areas of Mayatan Lake; Graham Watt for preparing maps; and Sal Figliuzzi for completion of the water balance for the lake. -

Prepared For

Volume 5D, ESA – Trans Mountain Pipeline ULC Socio-Economic Technical Reports Trans Mountain Expansion Project Traditional Land and Resource Use Technical Report An Elder reported that he and fellow Ermineskin Cree Nation community members once fished for whitefish, pickerel, perch, rainbow trout, pike and bull trout in Wabamun Lake. However, due to an oil spill in 2005, the water quality is now poor and fishing is not ideal. The fish are small and are believed to be unhealthy due to pollution. Although Ermineskin Cree Nation community members do not travel to the lake to fish, community members from nearby bands still report it to be an important fishing site. Community members report that some of their past fishing sites are no longer used. An Elder identified Pigeon Lake as a fishing site (Plate 5.1.7-1). Most fishing takes place at the south end of the lake. Historically, net fishing has been conducted. Community members reported that Buck Lake was the best spot to catch whitefish in the past. Chimney Creek, near Kootenay Plains, was also a known fishing site, now used for grazing livestock and not often used by Ermineskin Cree Nation members. A cabin was once situated there. Plate 5.1.7-1 Pigeon Lake from helicopter overflight. TABLE 5.1.7-5 FISHING SITES IDENTIFIED BY ERMINESKIN CREE NATION Approximate Distance and Current/Past Requested Direction from Project Site Description Use Mitigation 31 km south of RK 15.4 Coal Lake Current None 51.8 km southwest of RK 29.9 Pigeon Lake Current None 24.6 km south of RK 61.4 Along North Saskatchewan River for Current None trout, sturgeon, rainbow trout, catfish, suckers and walleye. -

WINDSPEAKER, December 30, 1988 CLOSE to HOME

-:---,,,,,,,,,. Page 2, WINDSPEAKER, December 30, 1988 CLOSE TO HOME SUSAN ENGE, Windspeaker Aunt saves child from fatal fire Everett Lambert upstairs was already full of Windspeaker Correspondent smoke I couldn't breath," she explained. LOUIS BULL RESERVE, The fire took place at Aka. five a.m. When Roasting reached the outside of the Pat Roasting, 29, doesn't building she says she heard feel like a hero, but in the the other two inside. "I fourth month of her preg- heard them trying to catch nancy this day care worker their breath," she explains. saved her five -month -old "If those fire alarms nephew from a house fire (smoke detectors) worked on this central Alberta that wouldn't of happened," reserve. Roasting, however, she remarks. lost her younger brother "I'm glad I saved my and sister -in -law in the nephew. But I don't Iike it blaze which started from a cigarette. that I couldn't do anything for my - The fire took place at brother and sister in -law, when I the home of Leon Roasting, especially 18, who along with his couldn't get in. She explains that the flames common -law wife, 18 -year- were intense near the area old Connie Little Poplar of where the other were. the nearby Samson Band, two It was reported that the died in the fire. blaze started from a Pat Roasting had decid- cigarette left burning when ed to stay overnight at her the couple fell brothers home and babysit asleep. for the young couple. She Media coverage for the wanted to stay overnight so fire has also drawn atten- Signing ceremony at government house: MAA Prez Larry Desmeules and Attorney General Ken Rostad she could walk to work the tion. -

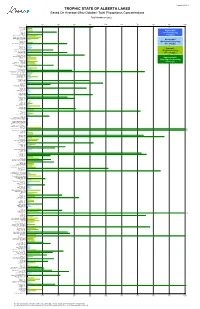

Trophic State of Alberta Lakes Based on Average Total Phosphorus

Created Feb 2013 TROPHIC STATE OF ALBERTA LAKES Based On Average (May-October) Total Phosphorus Concentrations Total Phosphorus (µg/L) 0 100 200 300 400 500 600 700 800 900 1000 * Adamson Lake Alix Lake * Amisk Lake * Angling Lake Oligotrophic * ‡ Antler Lake Arm Lake (Low Productivity) * Astotin Lake (<10 µg/L) * ‡ Athabasca (Lake) - Off Delta Baptiste Lake - North Basin Baptiste Lake - South Basin * ‡ Bare Creek Res. Mesotrophic * ‡ Barrier Lake ‡ Battle Lake (Moderate Productivity) * † Battle River Res. (Forestburg) (10 - 35 µg/L) Beartrap Lake Beauvais Lake Beaver Lake * Bellevue Lake Eutrophic * † Big Lake - East Basin * † Big Lake - West Basin (High Productivity) * Blackfalds Lake (35 - 100 µg/L) * † Blackmud Lake * ‡ Blood Indian Res. Bluet (South Garnier Lake) ‡ Bonnie Lake Hypereutrophic † Borden Lake * ‡ Bourque Lake (Very High Productivity) ‡ Buck Lake (>100 µg/L) Buffalo Lake - Main Basin Buffalo Lake - Secondary Bay * † Buffalo Lake (By Boyle) † Burntstick Lake Calling Lake * † Capt Eyre Lake † Cardinal Lake * ‡ Carolside Res. - Berry Creek Res. † Chain Lakes Res. - North Basin † Chain Lakes Res.- South Basin Chestermere Lake * † Chickakoo Lake * † Chickenhill Lake * Chin Coulee Res. * Clairmont Lake Clear (Barns) Lake Clear Lake ‡ Coal Lake * ‡ Cold Lake - English Bay ‡ Cold Lake - West Side ‡ Cooking Lake † Cow Lake * Crawling Valley Res. Crimson Lake Crowsnest Lake * † Cutbank Lake Dillberry Lake * Driedmeat Lake ‡ Eagle Lake ‡ Elbow Lake Elkwater Lake Ethel Lake * Fawcett Lake * † Fickle Lake * † Figure Eight Lake * Fishing Lake * Flyingshot Lake * Fork Lake * ‡ Fox Lake Res. Frog Lake † Garner Lake Garnier Lake (North) * George Lake * † Ghost Res. - Inside Bay * † Ghost Res. - Inside Breakwater ‡ Ghost Res. - Near Cochrane * Gleniffer Lake (Dickson Res.) * † Glenmore Res. -

Long Term Adequacy Metrics Nov 2018

Long Term Adequacy Metrics Nov 2018 Introduction The following report provides information on the long term adequacy of the Alberta electric energy market. The report contains metrics that include tables on generation projects under development and generation retirements, an annual reserve margin with a five year forecast period, a two year daily supply cushion, and a two year probabilistic assessment of the Alberta Interconnected Electric System (AIES). The Long Term Adequacy (LTA) Metrics provide an assessment and information that can be used to facilitate further assessments of long term adequacy. This report is updated quarterly in February, May, August, and November. Inquiries on the report can be made at [email protected]. Summary of Changes since Previous Report New Generation and Retirements Metric Projects completed and removed from list: N/A Generation Projects moved to “Active Construction”: TransCanada Scoria 318S Cogen Capital Power Whitla Wind Power – Phase 1 Generation projects moved to “Regulatory Approval”: Fortis Vauxhall Solar DER EDP Renewables Sharp Hills Wind RESC Forty Mile WAGF Turning Point Gen Canyon Creek PHES Fortis Stirling 67S DG PV Fortis Jenner 275S DER Capital Power Whitla Wind Power – Phase 2 Fortis Warner 344S DER Solar Greengate Power Wheatland Wind Generation projects that have been added to “Announced, Applied for AESO Interconnection, and/or Applied for Regulatory Approval”: FortisAlberta Kaybob 3 Cogen GP JOULE Kennedy Farm Solar NextEra Kitscoty MPC Wind Chephren Power Gas ATCO -

Mercury in Fish 2009-2013

2016 Mercury in Fish In Alberta Water Bodies 2009–2013 For more information on Fish Consumption Advisories Contact: Health Protection Branch Alberta Health P.O. Box 1360, Station Main Edmonton, Alberta, T5J 1S6 Telephone: 1-780-427-1470 ISBN: 978-0-7785- 8283-0 (Report) ISBN: 978-0-7785- 8284-7 (PDF) 2016 Government of Alberta Alberta Health, Health Protection Branch Mercury in Fish in Alberta Water Bodies 2009 – 2013 February 2016 Executive Summary Mercury enters the environment through various natural processes and human activities. Methylmercury is transformed from inorganic forms of mercury via methylation by micro-organisms in natural waters, and can accumulate in some fish. Humans are exposed to very low levels of mercury directly from the air, water and food. Fish consumers may be exposed to relatively higher levels of methylmercury by eating mercury-containing fish from local rivers and lakes. Methylmercury can accumulate in the human body over time. Because methylmercury is a known neurotoxin, it is necessary to limit human exposure. From 2009 to 2013, the Departments of Environment and Parks (AEP) and Health (AH) initiated a survey of mercury levels in fish in selected water bodies in Alberta. These water bodies are extensively accessed by the public for recreational activities. This report deals with (1) concentrations of total mercury levels in various fish species collected from the water bodies in Alberta, (2) estimated exposures, (3) fish consumption limits, (4) fish consumption advisories, and (5) health benefits of fish consumption. The results indicate that: 1. Concentrations of total mercury in fish in the water bodies in Alberta were within the ranges for the same fish species from other water bodies elsewhere in Canada and the United States.