1111111 Ii 74470 89397

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(Huichol) of Tateikita, Jalisco, Mexico

ETHNO-NATIONALIST POLITICS AND CULTURAL PRESERVATION: EDUCATION AND BORDERED IDENTITIES AMONG THE WIXARITARI (HUICHOL) OF TATEIKITA, JALISCO, MEXICO By BRAD MORRIS BIGLOW A DISSERTATION PRESENTED TO THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF FLORIDA 2001 Copyright 2001 by Brad Morris Biglow Dedicated to the Wixaritari of Tateikita and the Centro Educativo Tatutsi Maxa Kwaxi (CETMK): For teaching me the true meaning of what it is to follow in the footsteps of Tatutsi, and for allowing this teiwari to experience what you call tame tep+xeinuiwari. My heart will forever remain with you. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank my committee members–Dr. John Moore for being ever- supportive of my work with native peoples; Dr. Allan Burns for instilling in me the interest and drive to engage in Latin American anthropology, and helping me to discover the Huichol; Dr. Gerald Murray for our shared interests in language, culture, and education; Dr. Paul Magnarella for guidance and support in human rights activism, law, and intellectual property; and Dr. Robert Sherman for our mutual love of educational philosophy. Without you, this dissertation would be a mere dream. My life in the Sierra has been filled with countless names and memories. I would like to thank all of my “friends and family” at the CETMK, especially Carlos and Ciela, Marina and Ángel, Agustín, Pablo, Feliciano, Everardo, Amalia, Rodolfo, and Armando, for opening your families and lives to me. In addition, I thank my former students, including los chavos (Benjamín, Salvador, Miguel, and Catarino), las chicas (Sofía, Miguelina, Viviana, and Angélica), and los músicos (Guadalupe and Magdaleno). -

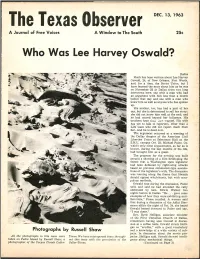

The Texas Observer DEC. 13, 1963

The Texas Observer DEC. 13, 1963 A Journal of Free Voices A Window to The South 25c Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald? Dallas Much has been written about Lee Harvey Oswald, 24, of New Orleans, Fort Worth, and, for a time, the Soviet Union, but I have learned the most about him as he was on November 22 in Dallas from two long interviews here, one with a man who had an argument with him less than a month before that day and one with a man who knew him as well as anyone who has spoken up. His mother, too, has had a part of her say, but she is determined to sell her story; she did not know him well at the end; and he had moved beyond her influence. His brothers kept then ovvr: cywnsel. His wife has yet to talk to reporters, other than a Life team who did not report much from her. And he is dead now. The argument occurred at a meeting of the Dallas chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union at Selectman Hall on the S.M.U. campus Oct. 25. Michael Paine, Os- wald's only close acquaintance, as far as is known, during the last months of his life, had brought him as a guest. The program for the evening was built around a showing of a film developing the theme that a Washington state legislator had been defeated by right'-'wing attacks based on previous communist-type associa- tions of the legislator's wife. The discussion was running along the theme that liberals should oppose witch-hunts, but with scru- pulous methods. -

Women Are Twice As Likely As Men to Have PTSD. You Just Don't Hear

Burden of War Women are twice as likely as men to have PTSD. You just don’t hear about it. BY ALEX HANNAFORD JUNE | 2014 IN THIS ISSUE ON THE COVER: ILLUSTRATION BY EDEL RODRIGUEZ Above: Crystal Bentley, who spent most of her childhood as a ward of the state, now advocates for improving foster care in Texas. PHOTO BY PATRICK MICHELS 18FOSTERING NEGLECT Foster care reforms are supposed to fix a flawed system. They could end up making things worse. by EMILY DEPRANG and BETH CORTEZ-NEAVEL Don’t CaLL THEM VICTIMS CULTURE Women veterans are twice as likely Building a better brick in Mason as men to experience PTSD. Nobody by Ian Dille OBSERVER 10 wants to talk about that. 26 by Alex Hannaford ONLINE Check out award-winning REGULARS 07 BIG BEAT 34 THE BOOK REPORT 42 POEM work by The 01 DIALOGUE Immigration reformers The compassionate Drift MOLLY National POLITICAL need to do it for imagination of by Christia 02 Journalism Prize INTELLIGENCE themselves Sarah Bird Madacsi Hoffman 06 STATE OF TEXAS by Cindy Casares by Robert Leleux winners—chosen 08 TYRANT’s FOE 43 STATE OF THE MEDIA by a distinguished 09 EdITORIAL 32 FILM 36 DIRECT QUOTE Rick Perry throws good panel of judges 09 BEN SARGENT’s Joe Lansdale’s genre- Buffalo soldiering in money after bad and announced at LOON STAR STATE bending novel Cold Balch Springs by Bill Minutaglio our annual prize in July jumps to the as told to Jen Reel dinner June 3—at big screen 44 FORREST FOR THE TREES texasobserver.org by Josh Rosenblatt 38 POSTCARDS Getting frivolous with The truth is out there? Greg Abbott by Patrick Michels by Forrest Wilder 45 EYE ON TEXAS by Sandy Carson A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES since 1954 OBSERVER VOLUME 106, NO. -

NAFTA Monitor Vol 1-6.Pm

NAFTA MONITOR Canada," WALL STREET JOURNAL, December 17, 1993; Alan L. Alder, "Autos Vol. 1 (1994) -- p.1 After NAFTA," AP, December 16, 1993; "Ford Will Build More in Mexico and In- Vol. 1, No. 1 Monday, December 20, 1993 crease Its Shipments South," INVESTOR'S BUSINESS DAILY, December 17, Headlines: 1993; Alva Senzek, "Trucks Make Comeback," EL FINANCIERO INTERNA- Vol. 2 (1995) -- p.36 COMPANIES SHIFT OPERATIONS TO MEXICO TIONAL, December 6-12, 1993. MEXICAN LABOR UNIONS TOO WEAK _________________________________________________ Vol. 3 (1996) -- p.80 MEXICO MAY NOT FOLLOW THROUGH WITH ENVIRONMENT PROMISES MEXICAN LABOR UNIONS TOO WEAK NAFTA WILL HURT MEXICAN INDUSTRIES As Mexican businesses suffer from increased com- Vol. 4 (1997) -- p.120 U.S. NAFTA PROTESTS CONTINUE petition under NAFTA, they will likely get tougher on _________________________________________________ workers to improve productivity. But an article in the Vol. 5 (1998) -- p.164 COMPANIES SHIFT OPERATIONS TO MEXICO NEW YORK TIMES says that under President Carlos In the weeks following the ratification of the North Salinas de Gortari Mexican labor unions are weaker Vol. 6 (1999) -- p.198 American Free Trade Agreement, many large compa- than they have been for 50 years and in a poor posi- nies announced plans to increase their operations in tion to deal with NAFTA's consequences. In testimony Mexico, often at the expense of U.S. or Canadian- before the U.S. Congress this year, Pharis Harvey, based manufacturing plants. executive director of the International Labor Rights Perhaps the quickest to take advantage of NAFTA Education and Research Fund, described organized Vol. -

November 22, 1996 • $1.75 a Journal of Free Voices

A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES NOVEMBER 22, 1996 • $1.75 THIS ISSUE FEATURES The Populists Return to Texas by Karen Olsson One hundred years ago, the Farmers' Alliance took on the banks, from the Texas Hill Country. This month, their political heirs take aim at the corporations. Communities Fight Pollution (& SOME Win) by Carol S. Stall 7 An EPA-sponsored roundtable in San Antonio brings together community stakeholders on environmental action. Meanwhile, a small Texas town wins one round. How the Contras Invaded the U.S. by Dennis Bernstein and Robert Knight 10 The recent allegations about CIA involvement in the crack trade are not exactly news. VOLUME 88, NO. 23 There has long been ample evidence of the dirty hands of U.S. "assets" in Nicaragua. A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES We will serve no group or party but will hew hard to the Blind Justice Comes to the Polls by W. Burns Taylor 13 truth as we find it and the right as we see it. We are ded- icated to the whole truth, to human values above all in- On November 5, a group of El Paso citizens exercised the right to a secret ballot terests, to the rights of human-kind as the foundation of for the very first time. Now they're hoping the State of Texas will see the light. democracy: we will take orders from none but our own conscience, and never will we overlook or misrepresent the truth to serve the interests of the powerful or cater to the ignoble in the human spirit. -

CV En Extenso

DR. PAUL M. LIFFMAN Curriculum Vitae, 2017 Domicilio: C Laurel 203-2 Zamora, Michoacán 59699 Correo: [email protected] Teléfono: 351-515-56-73 Nacionalidad: Estadounidense Página web: http://www.colmich.edu.mx/index.php/docencia-cea/planta-docente/2- uncategorised/129-liffman TÍTULO Ph.D. (Doctorado) en Antropología. Huichol Territoriality: Land Conflict and Cultural Representation in Western Mexico. University of Chicago, 30 agosto 2002. Comité de tesis: Paul Friedrich (director), Claudio Lomnitz, Friedrich Katz (lectores). PUESTOS ACADÉMICOS 2015- Coordinador, Centro de Estudios Antropológicos (CEA), El Colegio de Michoacán (Zamora, Michoacán, Mexico). 2014- Fellow, Center for Energy and Environmental Research in the Human Sciences (CENHS), Rice University (Houston), 2014-. 2012- Research Associate, Department of Anthropology, Rice University. 2004- Profesor-Investigador, Centro de Estudios Antropológicos, El Colegio de Michoacán, México. 2003-2004 Lector externo de avances de estudiantes de doctorado, Centro de Estudios Antropológicos, El Colegio de Michoacán. 2002-2003 Consultor de Exhibición (investigación, traducción Huichol/español-inglés, interpretación consecutiva, edición), “Our Peoples: Wixarika Tribal History”. National Museum of the American Indian, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC. BECAS y DISTINCIONES 2012 Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, Estancias Sabáticas y Posdoctorales al Extranjero para la Consolidación de Grupos de Investigación, Beca #168409 de año sabático en el Department of Anthropology, Rice University. 2007- Sistema Nacional de Investigadores, Nivel I, 2007-. 2007 Rockefeller Resident Fellowship in the Humanities, Latin American and Caribbean Studies Center, Northwestern University, Evanston IL, EUA. 2003 Investigador invitado, Centro de Estudios Mexicanos-Norteamericanos, Universidad de California-San Diego (puesto sin recursos económicos, invitación no aceptada). 2003 Estudioso invitado, Western Carolina University, Cullowhee, 26-30 abril 2001. -

They Left Behind

Hundreds have died anonymously crossing the Also border in South Texas. The things they carried SANDRA CISNEROS on her beloved house may help researchers unlock their identities. WENDY DAVIS on her past and future NOVEMBER | 2015 THE THINGS They Left Behind PHOTO ESSAY BY JEN REEL IN THIS ISSUE ON THE COVER: PHOTOS BY JEN REEL LEFT: Wendy Davis in her Austin condominium PHOTO BY JEN REEL 10THE INTERVIEW Wendy Davis’ mea culpa by Christopher Hooks THE THINGS RECKONING THE WAITING THEY LEFT WITH ROSIE GAME BEHIND What the 1977 death With a dearth of services OBSERVER 18 Clothes and jewelry 12 of a young McAllen 24 for the intellectually ONLINE found in unmarked graves may woman says about today’s disabled, Texans like Betty For our extended help give names to the nameless. anti-abortion laws. Calderon end up on the streets. Photo essay by Jen Reel by Alexa Garcia-Ditta by John Savage interview with Wendy Davis, including her REGULARS 07 GREATER STATE 36 BOOK EXCERPT 43 THE GRIMES SCENE take on the Texas 01 DIALOGUE From the Bottom, Up Sandra Cisneros What’s Your legislature and 02 POLITICAL by Ronnie Dugger On Her Problem, Man? Governor Greg INTELLIGENCE San Antonio House by Andrea Grimes Abbott, visit 06 STATE OF TEXAS 30 CULTURE texasobserver.org 08 STRANGEST STATE An Artist 38 POSTCARDS 44 LEFT HOOKS 09 EDITORIAL Interprets Violence Epitaph for The Gutting 09 BEN SARGENT’S by Michael Agresta an Alligator of Medicaid LOON STAR STATE by Asher Elbein by Christopher Hooks 34 FILM U.S. Fuel in a 42 POEM 45 EYE ON TEXAS Mexican Conflagration “How Far You by Guillermo Hernandez by Josh Rosenblatt Are From Me” by Eloísa Pérez-Lozano THE TEXAS OBSERVER (ISSN 0040-4519/USPS 541300), entire contents copyrighted © 2015, is published monthly (12 issues per year) by the Texas Democracy Foundation, a 501(c)3 nonprofit foundation, 307 W. -

Fighting Dirty Police Admired Barry Cooper When He Lied to Put Drug Dealers in Prison

Fighting Dirty Police admired Barry Cooper when he lied to put drug dealers in prison. Then he flipped the game on them. BY MICHAEL Mkb ON THE COVER Barry Cooper and Jello the pig face off PHOTO BY MATT WRIGHT-STEEL LOCATION AND PIG COURTESY OF GREEN GATE FARMS, AUSTIN 12TOO BLACK FOR SCHOOL by Foffest How race skews school discipline in Texas Brandarion Thomas (left) landed in court for grabbing a classmate. His mother thought that was too much. PHOTO BY FORREST WILDER FLIM—FLAM FIGHTING DIRTY by Melissa del Bosque by Michael May How Rick Perry has spun disastrous Police admired Barry Cooper when OBSERVER economic policies into winning politics 16 he lied to put drug dealers in prison. 06 Then he flipped the game on them. ONLINE See videos of Barry Cooper's REGULARS 26 DATELINE: 25 STATE OF THE MEDIA 2.1 URBAN COWGIRL stings and 01 DIALOGUE EL PASO Borderline Bias Space Politics watch a mini— 02 POLITICAL Recollections of a West by Bill Minutaglio by Ruth Pennebaker documentary on INTELLIGENCE Texas Dreamer the photo shoot 05 EDITORIAL by Elroy Bode 26 BOOK REVIEW 23 PURPLE STATE for the cover story. 05 BEN SARGENT'S Radical Write Populism vs. www.texasobserver.org LOON STAR STATE 22 CRITIC'S NOTEBOOK by Todd Moye WASPulism 19 HIGHTOWER REPORT Slack and Slash Cinema by Bob Moser 23 POETRY by Josh RosenbiaU by Alexander Maksik 29 EYE ON TEXAS by Sarah Wilson A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES SINCE 1954 I V* OBSERVER VOLUME 102, NO. 8 1111.0011E FOUNDING EDITOR Ronnie Dugger Turd Blossom Special EDITOR Bob Moser MANAGING EDITOR I was shocked to see an acquaintance post that he had become a fan of Karl Rove on Chris Tomlinson ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dave Mann Facebook ("Bush's Fist," April 16). -

2002 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 31, 2003

Mexico Page 1 of 30 Mexico Country Reports on Human Rights Practices - 2002 Released by the Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor March 31, 2003 Mexico is a federal republic composed of 31 states and a federal district, with an elected president and a bicameral legislature. In July 2000, voters elected President Vicente Fox Quesada of the Alliance for Change Coalition in historic elections that observers judged to be generally free and fair, and that ended the Institutional Revolutionary Party's (PRI) 71-year hold on the presidency. The peace process in Chiapas between the Zapatista National Liberation Army (EZLN) and the Government remained stalled. The EZLN has been silent since the passing of the Indigenous Rights and Culture law in August of 2001. There has been no dialogue between the EZLN and the Government since then because the EZLN refused to meet with the government’s representative, Luis H. Alvarez. Sporadic outbursts of politically motivated violence continued to occur throughout the country, particularly in the southern states of Chiapas, Guerrero, and Oaxaca. The judiciary is generally independent; however, on occasion, it was influenced by government authorities particularly at the state level. Corruption, inefficiency, impunity, disregard of the law, and lack of training are major problems. The police forces, which include federal and state judicial police, the Federal Preventive Police (PFP), municipal police, and various police auxiliary forces, have primary responsibility for law enforcement and maintenance of order within the country. However, the military played a large role in some law enforcement functions, primarily counternarcotics. There were approximately 5,300 active duty military personnel in the PFP as permitted by the 1972 Firearms and Explosives Law. -

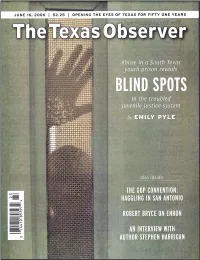

An Interview with Author Stephen Harrigan

JUNE 16, 2006 I $2.25 I OPENING THE EYES OF TEXAS FOR FIFTY ONE YEARS - „, , --, -,--4`— ., *.r. INAtnA li ,t4oel . ,rwe a 4 ..,,,, r....., • •,. ,n4.,.A .' -,-.e. *NA .o,,, ..,,,A .■..4. r.,' e.,, , <., by EMILY PYLE • * * 0 • 4 *111110't if *Ile,* Aft.,*** • *OP A * **, J. ** *fro, iti • AN INTERVIEW WITH AUTHOR STEPHEN HARRIGAN • JUNE 16, 2006 Dialogue TheTexas Observer WHAT ABOUT THE KIDS? universities regardless of their parents' As I sit in my classroom and observe immigration status. No Child Left FEATURES my students working, I wonder what Behind should mean the opportunity will become of them. The recent pro- for a college education for any child BLIND SPOTS 6 tests and the debate over immigration that wants it. Abuse at an Edinburg juvenile prison have only reminded me that many of The children should not be held reveals troubles in the my students do not have legal status back because of decisions made by Texas Youth Commission in this country. As the debate rages, it their parents. story by Emily Pyle seems that focus is on the adults that Anthony Colton photos by Amber Novak are illegal within our country, but Mesquite what about the children? FEAR AND LOATHING IN 10 Many of my students have been in BEACHES SAN ANTONIO the United States since a young age. Thank you for publicizing the immi- Republicans get riled up about taxes and Many have attended schools here in nent threats posed by recent develop- immigration at their state convention the United States since kindergarten. ment proposals to our public beaches. -

San Antonio OXIMS

The Texas Observer SEPT. 2, 1966 A Journal of Free Voices A Window to The South 25c On Being a Labor Organizer Eugene Nelson Austin views with former braceros and wetbacks, leaflet attacking a scab labor contractor First I'd like to say that I believe every- and someone told me that Cesar Chavez, bringing strikebreakers to a small vineyard one is basically selfish, so this piece won't director of the National Farm Workers As- we were striking. We distributed the leaf- deal with the moral aspects of the decision sociation, knew some people who could give let all over the neighborhood where the to become a labor organizer. me good stories. I went to him and im- scabs were recruited, and it worked. A When I was in my teens and first heard mediately he impressed me as the most month later the big Delano grape strike about unions and labor organizers it all humane man I had ever met. He offered me began and I became one of four picket seemed to me a drab and unromantic and a job as editor of a union newspaper he captains, in charge of a group of roving unexciting business. Later, after I had hoped to start publishing. I told him that pickets that swept through the vineyards worked at various low-paying jobs and when I finished my book I might take him looking for scabs, trying to persuade them learned some of the facts of life, I dis- up on it. By the time I finished my book to leave the fields and join us. -

Politics Becomes Personal Texas Lawmakers Have Made Themselves Part of Women’S Most Difficult Decisions

PERRY MUSCLES THE LCRA | GUATEMALA’S ARCHIVE OF TRAGEDY | SCIENCE VS. RELIGION IN GLEN ROSE 05 |APRIL 20 | 2011 | 2012 POLITICS BECOMES PERSONAL Texas lawmakers have made themselves part of women’s most difficult decisions. IN THIS ISSUE ON THE COVER PHOTO BY MATT STEEL LEFT Two sisters watch the exhumation of their mother and four small siblings. The sisters were present in August 1982 when soldiers shot their relatives, but they managed to escape. They spent 14 years in hiding in the mountains before resettling in a new community and later requesting the exhumation. Near the village of San Francisco Javier, Nebaj Quiché, 2000. PHOTO BY JONATHAN MOLLER 12THE LONG ROAD HOME by Saul Elbein Prosecutions, mass graves and the Police Archive provide clues in the deaths of thousands of Guatemalans. THE RIGHT NOT TO KNOW IT’S ALL ABOUT THE by Carolyn Jones water, BOYS The painful choice to terminate a by Mike Kanin OBSERVER 08 pregnancy is now—thanks to Texas’ new 20 Is Gov. Perry trying to take over sonogram law—just the beginning of the torment. the Lower Colorado River Aurhority? ONLINE Discuss the Texas REGULARS 25 BIG BEAT 37 NOVEL APPROACH 42 POEM sonogram law 01 DIALOGUE It’s Hard to Be Latina Harbury’s Fight for Alone and see readers’ 02 POLITICAL in Texas Human Rights by Damon V. Tapp reactions to INTELLIGENCE by Cindy Casares by Robert Leleux Carolyn Jones’ 06 TYRANT’s FOE 43 STATE OF THE MEDIA first-person 07 EdITORIAL 26 POSTCARDS 38 EAT YOUR WORDS Where’s the Line account (more 07 BEN SARGENT’s Tracking Creation Still Waters Between