They Left Behind

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Texas Observer DEC. 13, 1963

The Texas Observer DEC. 13, 1963 A Journal of Free Voices A Window to The South 25c Who Was Lee Harvey Oswald? Dallas Much has been written about Lee Harvey Oswald, 24, of New Orleans, Fort Worth, and, for a time, the Soviet Union, but I have learned the most about him as he was on November 22 in Dallas from two long interviews here, one with a man who had an argument with him less than a month before that day and one with a man who knew him as well as anyone who has spoken up. His mother, too, has had a part of her say, but she is determined to sell her story; she did not know him well at the end; and he had moved beyond her influence. His brothers kept then ovvr: cywnsel. His wife has yet to talk to reporters, other than a Life team who did not report much from her. And he is dead now. The argument occurred at a meeting of the Dallas chapter of the American Civil Liberties Union at Selectman Hall on the S.M.U. campus Oct. 25. Michael Paine, Os- wald's only close acquaintance, as far as is known, during the last months of his life, had brought him as a guest. The program for the evening was built around a showing of a film developing the theme that a Washington state legislator had been defeated by right'-'wing attacks based on previous communist-type associa- tions of the legislator's wife. The discussion was running along the theme that liberals should oppose witch-hunts, but with scru- pulous methods. -

Women Are Twice As Likely As Men to Have PTSD. You Just Don't Hear

Burden of War Women are twice as likely as men to have PTSD. You just don’t hear about it. BY ALEX HANNAFORD JUNE | 2014 IN THIS ISSUE ON THE COVER: ILLUSTRATION BY EDEL RODRIGUEZ Above: Crystal Bentley, who spent most of her childhood as a ward of the state, now advocates for improving foster care in Texas. PHOTO BY PATRICK MICHELS 18FOSTERING NEGLECT Foster care reforms are supposed to fix a flawed system. They could end up making things worse. by EMILY DEPRANG and BETH CORTEZ-NEAVEL Don’t CaLL THEM VICTIMS CULTURE Women veterans are twice as likely Building a better brick in Mason as men to experience PTSD. Nobody by Ian Dille OBSERVER 10 wants to talk about that. 26 by Alex Hannaford ONLINE Check out award-winning REGULARS 07 BIG BEAT 34 THE BOOK REPORT 42 POEM work by The 01 DIALOGUE Immigration reformers The compassionate Drift MOLLY National POLITICAL need to do it for imagination of by Christia 02 Journalism Prize INTELLIGENCE themselves Sarah Bird Madacsi Hoffman 06 STATE OF TEXAS by Cindy Casares by Robert Leleux winners—chosen 08 TYRANT’s FOE 43 STATE OF THE MEDIA by a distinguished 09 EdITORIAL 32 FILM 36 DIRECT QUOTE Rick Perry throws good panel of judges 09 BEN SARGENT’s Joe Lansdale’s genre- Buffalo soldiering in money after bad and announced at LOON STAR STATE bending novel Cold Balch Springs by Bill Minutaglio our annual prize in July jumps to the as told to Jen Reel dinner June 3—at big screen 44 FORREST FOR THE TREES texasobserver.org by Josh Rosenblatt 38 POSTCARDS Getting frivolous with The truth is out there? Greg Abbott by Patrick Michels by Forrest Wilder 45 EYE ON TEXAS by Sandy Carson A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES since 1954 OBSERVER VOLUME 106, NO. -

November 22, 1996 • $1.75 a Journal of Free Voices

A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES NOVEMBER 22, 1996 • $1.75 THIS ISSUE FEATURES The Populists Return to Texas by Karen Olsson One hundred years ago, the Farmers' Alliance took on the banks, from the Texas Hill Country. This month, their political heirs take aim at the corporations. Communities Fight Pollution (& SOME Win) by Carol S. Stall 7 An EPA-sponsored roundtable in San Antonio brings together community stakeholders on environmental action. Meanwhile, a small Texas town wins one round. How the Contras Invaded the U.S. by Dennis Bernstein and Robert Knight 10 The recent allegations about CIA involvement in the crack trade are not exactly news. VOLUME 88, NO. 23 There has long been ample evidence of the dirty hands of U.S. "assets" in Nicaragua. A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES We will serve no group or party but will hew hard to the Blind Justice Comes to the Polls by W. Burns Taylor 13 truth as we find it and the right as we see it. We are ded- icated to the whole truth, to human values above all in- On November 5, a group of El Paso citizens exercised the right to a secret ballot terests, to the rights of human-kind as the foundation of for the very first time. Now they're hoping the State of Texas will see the light. democracy: we will take orders from none but our own conscience, and never will we overlook or misrepresent the truth to serve the interests of the powerful or cater to the ignoble in the human spirit. -

Fighting Dirty Police Admired Barry Cooper When He Lied to Put Drug Dealers in Prison

Fighting Dirty Police admired Barry Cooper when he lied to put drug dealers in prison. Then he flipped the game on them. BY MICHAEL Mkb ON THE COVER Barry Cooper and Jello the pig face off PHOTO BY MATT WRIGHT-STEEL LOCATION AND PIG COURTESY OF GREEN GATE FARMS, AUSTIN 12TOO BLACK FOR SCHOOL by Foffest How race skews school discipline in Texas Brandarion Thomas (left) landed in court for grabbing a classmate. His mother thought that was too much. PHOTO BY FORREST WILDER FLIM—FLAM FIGHTING DIRTY by Melissa del Bosque by Michael May How Rick Perry has spun disastrous Police admired Barry Cooper when OBSERVER economic policies into winning politics 16 he lied to put drug dealers in prison. 06 Then he flipped the game on them. ONLINE See videos of Barry Cooper's REGULARS 26 DATELINE: 25 STATE OF THE MEDIA 2.1 URBAN COWGIRL stings and 01 DIALOGUE EL PASO Borderline Bias Space Politics watch a mini— 02 POLITICAL Recollections of a West by Bill Minutaglio by Ruth Pennebaker documentary on INTELLIGENCE Texas Dreamer the photo shoot 05 EDITORIAL by Elroy Bode 26 BOOK REVIEW 23 PURPLE STATE for the cover story. 05 BEN SARGENT'S Radical Write Populism vs. www.texasobserver.org LOON STAR STATE 22 CRITIC'S NOTEBOOK by Todd Moye WASPulism 19 HIGHTOWER REPORT Slack and Slash Cinema by Bob Moser 23 POETRY by Josh RosenbiaU by Alexander Maksik 29 EYE ON TEXAS by Sarah Wilson A JOURNAL OF FREE VOICES SINCE 1954 I V* OBSERVER VOLUME 102, NO. 8 1111.0011E FOUNDING EDITOR Ronnie Dugger Turd Blossom Special EDITOR Bob Moser MANAGING EDITOR I was shocked to see an acquaintance post that he had become a fan of Karl Rove on Chris Tomlinson ASSOCIATE EDITOR Dave Mann Facebook ("Bush's Fist," April 16). -

An Interview with Author Stephen Harrigan

JUNE 16, 2006 I $2.25 I OPENING THE EYES OF TEXAS FOR FIFTY ONE YEARS - „, , --, -,--4`— ., *.r. INAtnA li ,t4oel . ,rwe a 4 ..,,,, r....., • •,. ,n4.,.A .' -,-.e. *NA .o,,, ..,,,A .■..4. r.,' e.,, , <., by EMILY PYLE • * * 0 • 4 *111110't if *Ile,* Aft.,*** • *OP A * **, J. ** *fro, iti • AN INTERVIEW WITH AUTHOR STEPHEN HARRIGAN • JUNE 16, 2006 Dialogue TheTexas Observer WHAT ABOUT THE KIDS? universities regardless of their parents' As I sit in my classroom and observe immigration status. No Child Left FEATURES my students working, I wonder what Behind should mean the opportunity will become of them. The recent pro- for a college education for any child BLIND SPOTS 6 tests and the debate over immigration that wants it. Abuse at an Edinburg juvenile prison have only reminded me that many of The children should not be held reveals troubles in the my students do not have legal status back because of decisions made by Texas Youth Commission in this country. As the debate rages, it their parents. story by Emily Pyle seems that focus is on the adults that Anthony Colton photos by Amber Novak are illegal within our country, but Mesquite what about the children? FEAR AND LOATHING IN 10 Many of my students have been in BEACHES SAN ANTONIO the United States since a young age. Thank you for publicizing the immi- Republicans get riled up about taxes and Many have attended schools here in nent threats posed by recent develop- immigration at their state convention the United States since kindergarten. ment proposals to our public beaches. -

San Antonio OXIMS

The Texas Observer SEPT. 2, 1966 A Journal of Free Voices A Window to The South 25c On Being a Labor Organizer Eugene Nelson Austin views with former braceros and wetbacks, leaflet attacking a scab labor contractor First I'd like to say that I believe every- and someone told me that Cesar Chavez, bringing strikebreakers to a small vineyard one is basically selfish, so this piece won't director of the National Farm Workers As- we were striking. We distributed the leaf- deal with the moral aspects of the decision sociation, knew some people who could give let all over the neighborhood where the to become a labor organizer. me good stories. I went to him and im- scabs were recruited, and it worked. A When I was in my teens and first heard mediately he impressed me as the most month later the big Delano grape strike about unions and labor organizers it all humane man I had ever met. He offered me began and I became one of four picket seemed to me a drab and unromantic and a job as editor of a union newspaper he captains, in charge of a group of roving unexciting business. Later, after I had hoped to start publishing. I told him that pickets that swept through the vineyards worked at various low-paying jobs and when I finished my book I might take him looking for scabs, trying to persuade them learned some of the facts of life, I dis- up on it. By the time I finished my book to leave the fields and join us. -

Politics Becomes Personal Texas Lawmakers Have Made Themselves Part of Women’S Most Difficult Decisions

PERRY MUSCLES THE LCRA | GUATEMALA’S ARCHIVE OF TRAGEDY | SCIENCE VS. RELIGION IN GLEN ROSE 05 |APRIL 20 | 2011 | 2012 POLITICS BECOMES PERSONAL Texas lawmakers have made themselves part of women’s most difficult decisions. IN THIS ISSUE ON THE COVER PHOTO BY MATT STEEL LEFT Two sisters watch the exhumation of their mother and four small siblings. The sisters were present in August 1982 when soldiers shot their relatives, but they managed to escape. They spent 14 years in hiding in the mountains before resettling in a new community and later requesting the exhumation. Near the village of San Francisco Javier, Nebaj Quiché, 2000. PHOTO BY JONATHAN MOLLER 12THE LONG ROAD HOME by Saul Elbein Prosecutions, mass graves and the Police Archive provide clues in the deaths of thousands of Guatemalans. THE RIGHT NOT TO KNOW IT’S ALL ABOUT THE by Carolyn Jones water, BOYS The painful choice to terminate a by Mike Kanin OBSERVER 08 pregnancy is now—thanks to Texas’ new 20 Is Gov. Perry trying to take over sonogram law—just the beginning of the torment. the Lower Colorado River Aurhority? ONLINE Discuss the Texas REGULARS 25 BIG BEAT 37 NOVEL APPROACH 42 POEM sonogram law 01 DIALOGUE It’s Hard to Be Latina Harbury’s Fight for Alone and see readers’ 02 POLITICAL in Texas Human Rights by Damon V. Tapp reactions to INTELLIGENCE by Cindy Casares by Robert Leleux Carolyn Jones’ 06 TYRANT’s FOE 43 STATE OF THE MEDIA first-person 07 EdITORIAL 26 POSTCARDS 38 EAT YOUR WORDS Where’s the Line account (more 07 BEN SARGENT’s Tracking Creation Still Waters Between -

A TICKET for the CHOW TRAIN Can a Car Town Make PERFORMING ‘TEXAS’ in the PANHANDLE Room for Bikes?

ALSO A TICKET FOR THE CHOW TRAIN Can a Car Town Make PERFORMING ‘TEXAS’ IN THE PANHANDLE Room for Bikes? JULY | 2015 Migrant bodies buried in shallow unmarked graves and the Texas Ranger who found nothing wrong with it. Graves of Shame BY JOHN CARLOS FREY IN THIS ISSUE ON THE COVER: ILLUSTRATION BY TAYLOR CALLERY LEFT: Joan Cheever, founder of the Chow Train, prepares green beans for her weekly Tuesday-night outings to feed the homeless San Antonio. PHOTO BY JEN REEL 18SAVING GRACE When Joan Cheever was ticketed as she fed the needy in San Antonio, she invoked the state’s Religious Freedom Restoration Act in her defense. Can it be illegal to share food? by Katie Sherrod GRAVE CONCERN CULTURE Undocumented migrants who die in In the Panhandle, in summer, Texas Brooks County are often buried in takes the stage in Palo Duro Canyon. OBSERVER 10 mass graves without identification or 24 A lot has changed since the musical honor. They may also be buried illegally. was first performed 50 years ago. A lot hasn’t. ONLINE by John Carlos Frey by Robyn Ross There’s no rest for the wicked in REGULARS 07 GREATER STATE 36 DIRECT QUOTE 43 STATE OF THE MEDIA the dogs days of 01 DIALOGUE Outside the Lines Keeper of the Creek #nofilter summer. Check 02 POLITICAL by Claire Bow as told to Jen Reel by Andrea Grimes out original INTELLIGENCE reporting on 06 STATE OF TEXAS 32 FILM 38 POSTCARDS 44 FORREST FOR THE TREES mobile home 08 STRANGEST STATE Wild Horses Doesn’t Kicking Cars in Houston Home in the Crosshairs park profiteering 09 EDITORIAL Know When to Say Nay by Ian Dille by Forrest Wilder and unregulated 09 BEN SARGENT’S by Josh Rosenblatt LOON STAR STATE 42 POEM 45 EYE ON TEXAS waste disposal 34 THE BOOK REPORT “Rattlebone’s Rant” by Jay Lee at texasobserver.org In Her Words by B.R. -

The Texas Observer AUGUST 18, 1967 a Journal of Free Voices a Window to the South 25C NOT LIKE IT USED to BE State Politicians Crowd Into Texas Labor's Spotlight

The Texas Observer AUGUST 18, 1967 A Journal of Free Voices A Window to The South 25c NOT LIKE IT USED TO BE State Politicians Crowd into Texas Labor's Spotlight Fort Worth the Starr county strikers that way. Chavez couple of days after the labor convention, The days when organized labor was said, of the Texas strike, "We have pos- told a Texas Liberal Democrats audience castigated as un-American, subversive, or sibly made more mistakes here than any that "I don't know if I will be a candidate communistic are past in Texas. Now the place we have tried to organize workers. for anything next year. I say this in all sin- unquestioned influence of the state Ameri- In the Rio Grande Valley the strike came cerity. I will not be a volunteer for can Federation of Labor-Congress of In- about overnight and we had to take it any Kamikaze missions." Spears had been dustrial Organizations has caused Texas over immediately, ... (We eventually are widely considered to be planning a state- politicians of all persuasions to treat the going to have a farm workers union, re- wide race of some sort next year, prob- labor group with respect it was nowhere gardless how long it lakes, regardless of ably for lieutenant governor or, .perhaps, near commanding a few years back. "I've how many Texas Rangers there are in Rio attorney general. He has been making seen state AFL-CIO conventions where you Grande City, and regardless of the poli- frequent speeches around the state this couldn't get an office holder in the same ticians who do not want-to help us." Roy year. -

John Henry Faulk O Ronnie Dugger O Molly Ivins O C Handler Davidson O

THE TEXAS BSERVERL A Journal of Free Voices December 30, 1977 500 john henry faulk o ronnie dugger o molly ivins o c handler davidson o jim h ightower o ralph yarborou gh o Jan Jarboe on maur y maverick 0 ben sargen t o mary alice davis 0 year's end Vol. 69, Austin Well, here's no. 25. Eleven months and 24 issues ago, we promised "a new start for an old magazine" and began The Texas inveighing in particular against the ugly (though often unno- ticed) shape of things on the corporate horizon. Not this time, OBSERVER though. We've chosen to downplay the storms, sorrows and ©The Texas Observer Publishing Co., 1977. seductions of the world for this issue, and to avert our gaze ever Ronnie Dugger, Publisher so slightly from the doings of the corporate right wing of Texas. At year's end, for the rash hell of it, we've asked several of the Vol. 69, No. 25 December 30, 1977 magazine's contributors to carry on as they see fit. Incorporating the State Observer and the East Texas Demo- Publisher Dugger, happily domiciled in his native San crat, which in turn incorporated the Austin Forum-Advocate. Antonio after an absence of some years, pretty much approves EDITOR Jim Hightower of what he sees and feels in the state's second largest city. The MANAGING EDITOR Lawrence Walsh first in his series of letters from San Antonio begins on page 4. ASSOCIATE EDITOR Laura Richardson Ben Sargent and Mary Alice Davis pay a '77 tribute to the EDITOR AT LARGE Ronnie Dugger nick and rack of human folly (Texas branch) on pages 6 and 7. -

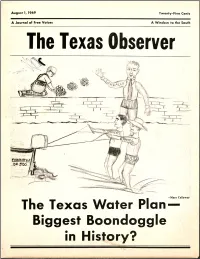

Ustxtxb Obs 1969 08 01 Issue.Pdf

August 1, 1969 Twenty-Five Cents A Journal of Free Voices A Window to the South The Texas Observer —Mary Callaway The Texas Water Plan • Biggest Boondoggle in History? I seeeroliaed `I/ate ;4941644e tle 7Piater aad4 Austin is bound to be too low (despite $500 handful of legislators fully understood After months of attempting to study the million permitted for increased costs due what they were voting on. Next time the so-called "Texas Water Plan," Observer to inflation), since the board used 1967 water issue comes up, they probably will editors have come to the conclusion that cost estimates. The plan does not take into not understand the issues much better. proposition No. 2 on the Aug. 5 ballot, the consideration the fact that the $3.5 billion The Observer is tried to gather to- $3.5 billion bond issue for water develop- bond issue would cost another $3.5 to $4 gether in this issue most of the valid ment, should be defeated, indeed, devas- billion in interest at prevailing rates. arguments againUl5assing the water bonds. tated. We are devoting a great deal of space to The "plan" is not really a plan at all, but The water board and some of the state's these arguments, basically because they a highly speculative, sometimes dishonest, biologists seem to disagree on the effects of have not been presented in the daily press. and always optimistic scheme for spending the giant canal system on the ecology of We also have tried to balance these criti- a monumental hunk of Texans' money, the state. -

NO PICNIC at SPEAKING ROCK 4 Slush of Lies from the Mainstream Media Washington Lobbyists Unhappy in Marriage, Married Immedi- GOP Corporatist Propaganda Machine

, itiveltvok %%%10100 000,-0 4040,00.AWk Also: The TO Interviews Houston Mayor Bill White Lou Dubose on the Tigua shakedown 1 11 1 1 And "Wonderful People," by Kate Hill Cantrill 0 74470 89397 DECEMBER 17, 2004 Texas Observer POST, POST-ELECTION TURNING 50 FEATURES President Bush's heady re-election vic- Happy 50th! Your service is invaluable tory after a dismal first-term is like that and greatly appreciated out here in the classic: A gentleman who had been very NO PICNIC AT SPEAKING ROCK 4 slush of lies from the mainstream media Washington lobbyists unhappy in marriage, married immedi- GOP corporatist propaganda machine. shakedown Indian casinos ately after his wife died—it was a "tri- Keep on keepin' on. by Lou Dubose umph of hope over experience." Happy holidays and thank you. Ted Corin Robert von Tobel THE WHITE STUFF 10 Austin Bellevue, WA The Observer talks with Houston Mayor Bill White After reading your interview with James As a TomPaine.com devotee, I read their by Jake Bernstein Aldrete ("The Road Back to Power," excerpts from your "observations." So, November 19), I now know how I am today I send you best wishes for contin- DEPARTMENTS viewed. I am a Republican ("That means ued output and a HAPPY 50th BIRTH- taking on the bastards but doing it in a DAY!! DIALOGUE 2 language of faith.") So in your view I am Kathleen McKenna a bastard. Don't forget to call me igno- EDITORIAL 3 Via e-mail Grinchy Nation rant, homophobic, and racist. Then there was, "We also need a true Happy birthday and thanks for Molly DATELINE LUBBOCK 8 realization of how low the Republicans Ivins, Jim Hightower, and Ronnie Dugger.