**************W****************************** * Reproductions Supplied by EDRS Are the Best That Can Be Made

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

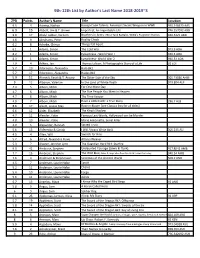

9Th-12Th List by Author's Last Name 2018-2019~S

9th-12th List by Author's Last Name 2018-2019~S ZPD Points Author's Name Title Location 9.5 4 Aaseng, Nathan Navajo Code Talkers: America's Secret Weapon in WWII 940.548673 AAS 6.9 15 Abbott, Jim & T. Brown Imperfect, An Improbable Life 796.357092 ABB 9.9 17 Abdul-Jabbar, Kareem Brothers in Arms: 761st Tank Battalio, WW2's Forgotten Heroes 940.5421 ABD 4.6 9 Abrahams, Peter Reality Check 6.2 8 Achebe, Chinua Things Fall Apart 6.1 1 Adams, Simon The Cold War 973.9 ADA 8.2 1 Adams, Simon Eyewitness - World War I 940.3 ADA 8.3 1 Adams, Simon Eyewitness- World War 2 940.53 ADA 7.9 4 Adkins, Jan Thomas Edison: A Photographic Story of a Life 92 EDI 5.7 19 Adornetto, Alexandra Halo Bk1 5.7 17 Adornetto, Alexandra Hades Bk2 5.9 11 Ahmedi, Farah & T. Ansary The Other Side of the Sky 305.23086 AHM 9 12 Albanov, Valerian In the Land of White Death 919.804 ALB 4.3 5 Albom, Mitch For One More Day 4.7 6 Albom, Mitch The Five People You Meet in Heaven 4.7 6 Albom, Mitch The Time Keeper 4.9 7 Albom, Mitch Have a Little Faith: a True Story 296.7 ALB 8.6 17 Alcott, Louisa May Rose in Bloom [see Classics lists for all titles] 6.6 12 Alder, Elizabeth The King's Shadow 4.7 11 Alender, Katie Famous Last Words, Hollywood can be Murder 4.8 10 Alender, Katie Marie Antoinette, Serial Killer 4.9 5 Alexander, Hannah Sacred Trust 5.6 13 Aliferenka & Ganda I Will Always Write Back 305.235 ALI 4.5 4 Allen, Will Swords for Hire 5.2 6 Allred, Alexandra Powe Atticus Weaver 5.3 7 Alvarez, Jennifer Lynn The Guardian Herd Bk1: Starfire 9.0 42 Ambrose, Stephen Undaunted Courage -

Expert's Views on the Dilemmas of African Writers

EXPERTS’ VIEWS ON THE DILEMMAS OF AFRICAN WRITERS: CONTRIBUTIONS, CHALLENGES AND PROSPECTS By Sarah Kaddu Abstract African writers have faced the “dilemma syndrome” in the execution of their mission. They have faced not only “bed of roses” but also “the bed of thorns”. On one hand, African writers such as Chinua Achebe have made a fortune from royalties from his African Writers’ Series (AWS) and others such as Wole Soyinka, Ben Okri and Naruddin Farah have depended on prestigious book prizes. On the other hand, some African writers have also, according to Larson (2001), faced various challenges: running bankrupt, political and social persecution, business sabotage, loss of life or escaping catastrophe by “hair breadth”. Nevertheless, the African writers have persisted with either success or agony. Against this backdrop, this paper examines the experts’ views on the contributions of African writers to the extending of national and international frontiers in publishing as well as the attendant handicaps before proposing strategies for overcoming the challenges encountered. The specific objectives are to establish some of the works published by the African writers; determine the contribution of the works published by African writers to in terms of political, economic, and cultural illumination; examine the challenges encountered in the publishing process of the African writers’ works; and, predict trends in the future of the African writers’ series. The study findings illuminate on the contributions to political, social, gender, cultural re-awakening and documentation, poetry and literature, growth of the book trade and publishing industry/employment in addition to major challenges encountered. The study entailed extensive analysis of literature, interviews with experts on African writings from the Uganda Christian University and Makerere University, and African Writers Trust; focus group discussions with publishers, and a few selected African writers, and a review of the selected pioneering publications of African writers. -

General Vertical Files Anderson Reading Room Center for Southwest Research Zimmerman Library

“A” – biographical Abiquiu, NM GUIDE TO THE GENERAL VERTICAL FILES ANDERSON READING ROOM CENTER FOR SOUTHWEST RESEARCH ZIMMERMAN LIBRARY (See UNM Archives Vertical Files http://rmoa.unm.edu/docviewer.php?docId=nmuunmverticalfiles.xml) FOLDER HEADINGS “A” – biographical Alpha folders contain clippings about various misc. individuals, artists, writers, etc, whose names begin with “A.” Alpha folders exist for most letters of the alphabet. Abbey, Edward – author Abeita, Jim – artist – Navajo Abell, Bertha M. – first Anglo born near Albuquerque Abeyta / Abeita – biographical information of people with this surname Abeyta, Tony – painter - Navajo Abiquiu, NM – General – Catholic – Christ in the Desert Monastery – Dam and Reservoir Abo Pass - history. See also Salinas National Monument Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Afghanistan War – NM – See also Iraq War Abousleman – biographical information of people with this surname Abrams, Jonathan – art collector Abreu, Margaret Silva – author: Hispanic, folklore, foods Abruzzo, Ben – balloonist. See also Ballooning, Albuquerque Balloon Fiesta Acequias – ditches (canoas, ground wáter, surface wáter, puming, water rights (See also Land Grants; Rio Grande Valley; Water; and Santa Fe - Acequia Madre) Acequias – Albuquerque, map 2005-2006 – ditch system in city Acequias – Colorado (San Luis) Ackerman, Mae N. – Masonic leader Acoma Pueblo - Sky City. See also Indian gaming. See also Pueblos – General; and Onate, Juan de Acuff, Mark – newspaper editor – NM Independent and -

Imagining Outer Space Also by Alexander C

Imagining Outer Space Also by Alexander C. T. Geppert FLEETING CITIES Imperial Expositions in Fin-de-Siècle Europe Co-Edited EUROPEAN EGO-HISTORIES Historiography and the Self, 1970–2000 ORTE DES OKKULTEN ESPOSIZIONI IN EUROPA TRA OTTO E NOVECENTO Spazi, organizzazione, rappresentazioni ORTSGESPRÄCHE Raum und Kommunikation im 19. und 20. Jahrhundert NEW DANGEROUS LIAISONS Discourses on Europe and Love in the Twentieth Century WUNDER Poetik und Politik des Staunens im 20. Jahrhundert Imagining Outer Space European Astroculture in the Twentieth Century Edited by Alexander C. T. Geppert Emmy Noether Research Group Director Freie Universität Berlin Editorial matter, selection and introduction © Alexander C. T. Geppert 2012 Chapter 6 (by Michael J. Neufeld) © the Smithsonian Institution 2012 All remaining chapters © their respective authors 2012 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No portion of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission or in accordance with the provisions of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988, or under the terms of any licence permitting limited copying issued by the Copyright Licensing Agency, Saffron House, 6–10 Kirby Street, London EC1N 8TS. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. The authors have asserted their rights to be identified as the authors of this work in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. First published 2012 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN Palgrave Macmillan in the UK is an imprint of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS. -

TRANSIENT LUNAR PHENOMENA: REGULARITY and REALITY Arlin P

The Astrophysical Journal, 697:1–15, 2009 May 20 doi:10.1088/0004-637X/697/1/1 C 2009. The American Astronomical Society. All rights reserved. Printed in the U.S.A. TRANSIENT LUNAR PHENOMENA: REGULARITY AND REALITY Arlin P. S. Crotts Department of Astronomy, Columbia University, Columbia Astrophysics Laboratory, 550 West 120th Street, New York, NY 10027, USA Received 2007 June 27; accepted 2009 February 20; published 2009 April 30 ABSTRACT Transient lunar phenomena (TLPs) have been reported for centuries, but their nature is largely unsettled, and even their existence as a coherent phenomenon is controversial. Nonetheless, TLP data show regularities in the observations; a key question is whether this structure is imposed by processes tied to the lunar surface, or by terrestrial atmospheric or human observer effects. I interrogate an extensive catalog of TLPs to gauge how human factors determine the distribution of TLP reports. The sample is grouped according to variables which should produce differing results if determining factors involve humans, and not reflecting phenomena tied to the lunar surface. Features dependent on human factors can then be excluded. Regardless of how the sample is split, the results are similar: ∼50% of reports originate from near Aristarchus, ∼16% from Plato, ∼6% from recent, major impacts (Copernicus, Kepler, Tycho, and Aristarchus), plus several at Grimaldi. Mare Crisium produces a robust signal in some cases (however, Crisium is too large for a “feature” as defined). TLP count consistency for these features indicates that ∼80% of these may be real. Some commonly reported sites disappear from the robust averages, including Alphonsus, Ross D, and Gassendi. -

Paintings by John W. Alexander ; Sculpture by Chester Beach

SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, DECEMBER 12 1916 TO JANUARY 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE 0 SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS OF WORK BY THE FOLLOWING ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO DEC. 12, 1916 TO JAN. 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN WHITE ALEXANDER OHN vV. ALEXANDER. Born, Pittsburgh, J Pennsylvania, 1856. Died, New York, May 31, 1915. Studied at the Royal Academy, Munich, and with Frank Duveneck. Societaire of Societe Nationale des Beaux Arts, Paris; Member of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, London; Societe Nouvelle, Paris ; Societaire of the Royal Society of Fine Arts, Brussels; President of the National Academy of Design, New York; President of the Natiomrl Academy Association; President of the National Society of Mural Painters, New York; Ex- President of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, New York; American Academy of Arts and Letters; Vice-President of the National Fine Arts Federation, Washington, D. C.; Member of the Architectural League, Fine Arts Federation and Fine Arts Society, New York; Honorary Member of the Secession Society, Munich, and of the Secession Society, Vienna; Hon- orary Member of the Royal Society of British Artists, of the American Institute of Architects and of the New York Society of Illustrators; President of the School Art League, New York; Trustee of the New York Public Library; Ex-President of the MacDowell Club, New York; Trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Trustee of the American Academy in Rome; Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, France; Honorary Degree of Master of Arts, Princeton University, 1892, and of Doctor of Literature, Princeton, 1909. -

13Th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture

13th Valley John M. Del Vecchio Fiction 25.00 ABC of Architecture James F. O’Gorman Non-fiction 38.65 ACROSS THE SEA OF GREGORY BENFORD SF 9.95 SUNS Affluent Society John Kenneth Galbraith 13.99 African Exodus: The Origins Christopher Stringer and Non-fiction 6.49 of Modern Humanity Robin McKie AGAINST INFINITY GREGORY BENFORD SF 25.00 Age of Anxiety: A Baroque W. H. Auden Eclogue Alabanza: New and Selected Martin Espada Poetry 24.95 Poems, 1982-2002 Alexandria Quartet Lawrence Durell ALIEN LIGHT NANCY KRESS SF Alva & Irva: The Twins Who Edward Carey Fiction Saved a City And Quiet Flows the Don Mikhail Sholokhov Fiction AND ETERNITY PIERS ANTHONY SF ANDROMEDA STRAIN MICHAEL CRICHTON SF Annotated Mona Lisa: A Carol Strickland and Non-fiction Crash Course in Art History John Boswell From Prehistoric to Post- Modern ANTHONOLOGY PIERS ANTHONY SF Appointment in Samarra John O’Hara ARSLAN M. J. ENGH SF Art of Living: The Classic Epictetus and Sharon Lebell Non-fiction Manual on Virtue, Happiness, and Effectiveness Art Attack: A Short Cultural Marc Aronson Non-fiction History of the Avant-Garde AT WINTER’S END ROBERT SILVERBERG SF Austerlitz W.G. Sebald Auto biography of Miss Jane Ernest Gaines Fiction Pittman Backlash: The Undeclared Susan Faludi Non-fiction War Against American Women Bad Publicity Jeffrey Frank Bad Land Jonathan Raban Badenheim 1939 Aharon Appelfeld Fiction Ball Four: My Life and Hard Jim Bouton Time Throwing the Knuckleball in the Big Leagues Barefoot to Balanchine: How Mary Kerner Non-fiction to Watch Dance Battle with the Slum Jacob Riis Bear William Faulkner Fiction Beauty Robin McKinley Fiction BEGGARS IN SPAIN NANCY KRESS SF BEHOLD THE MAN MICHAEL MOORCOCK SF Being Dead Jim Crace Bend in the River V. -

Democratic Citizenship in the Heart of Empire Dissertation Presented In

POLITICAL ECONOMY OF AMERICAN EDUCATION: Democratic Citizenship in the Heart of Empire Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of the Ohio State University Thomas Michael Falk B.A., M.A. Graduate Program in Education The Ohio State University Summer, 2012 Committee Members: Bryan Warnick (Chair), Phil Smith, Ann Allen Copyright by Thomas Michael Falk 2012 ABSTRACT Chief among the goals of American education is the cultivation of democratic citizens. Contrary to State catechism delivered through our schools, America was not born a democracy; rather it emerged as a republic with a distinct bias against democracy. Nonetheless we inherit a great demotic heritage. Abolition, the labor struggle, women’s suffrage, and Civil Rights, for example, struck mighty blows against the established political and economic power of the State. State political economies, whether capitalist, socialist, or communist, each express characteristics of a slave society. All feature oppression, exploitation, starvation, and destitution as constitutive elements. In order to survive in our capitalist society, the average person must sell the contents of her life in exchange for a wage. Fundamentally, I challenge the equation of State schooling with public and/or democratic education. Our schools have not historically belonged to a democratic public. Rather, they have been created, funded, and managed by an elite class wielding local, state, and federal government as its executive arms. Schools are economic institutions, serving a division of labor in the reproduction of the larger economy. Rather than the school, our workplaces are the chief educational institutions of our lives. -

Regional Oral History Off Ice University of California the Bancroft Library Berkeley, California

Regional Oral History Off ice University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California Richard B. Gump COMPOSER, ARTIST, AND PRESIDENT OF GUMP'S, SAN FRANCISCO An Interview Conducted by Suzanne B. Riess in 1987 Copyright @ 1989 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of Northern California, the West,and the Nation. Oral history is a modern research technique involving an interviewee and an informed interviewer in spontaneous conversation. The taped record is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The resulting manuscript is typed in final form, indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between the University of California and Richard B. Gump dated 7 March 1988. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. No part of the manuscript may be quoted for publication without the written permission of the Director of The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

CALIFORNIA's NORTH COAST: a Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors

CALIFORNIA'S NORTH COAST: A Literary Watershed: Charting the Publications of the Region's Small Presses and Regional Authors. A Geographically Arranged Bibliography focused on the Regional Small Presses and Local Authors of the North Coast of California. First Edition, 2010. John Sherlock Rare Books and Special Collections Librarian University of California, Davis. 1 Table of Contents I. NORTH COAST PRESSES. pp. 3 - 90 DEL NORTE COUNTY. CITIES: Crescent City. HUMBOLDT COUNTY. CITIES: Arcata, Bayside, Blue Lake, Carlotta, Cutten, Eureka, Fortuna, Garberville Hoopa, Hydesville, Korbel, McKinleyville, Miranda, Myers Flat., Orick, Petrolia, Redway, Trinidad, Whitethorn. TRINITY COUNTY CITIES: Junction City, Weaverville LAKE COUNTY CITIES: Clearlake, Clearlake Park, Cobb, Kelseyville, Lakeport, Lower Lake, Middleton, Upper Lake, Wilbur Springs MENDOCINO COUNTY CITIES: Albion, Boonville, Calpella, Caspar, Comptche, Covelo, Elk, Fort Bragg, Gualala, Little River, Mendocino, Navarro, Philo, Point Arena, Talmage, Ukiah, Westport, Willits SONOMA COUNTY. CITIES: Bodega Bay, Boyes Hot Springs, Cazadero, Cloverdale, Cotati, Forestville Geyserville, Glen Ellen, Graton, Guerneville, Healdsburg, Kenwood, Korbel, Monte Rio, Penngrove, Petaluma, Rohnert Part, Santa Rosa, Sebastopol, Sonoma Vineburg NAPA COUNTY CITIES: Angwin, Calistoga, Deer Park, Rutherford, St. Helena, Yountville MARIN COUNTY. CITIES: Belvedere, Bolinas, Corte Madera, Fairfax, Greenbrae, Inverness, Kentfield, Larkspur, Marin City, Mill Valley, Novato, Point Reyes, Point Reyes Station, Ross, San Anselmo, San Geronimo, San Quentin, San Rafael, Sausalito, Stinson Beach, Tiburon, Tomales, Woodacre II. NORTH COAST AUTHORS. pp. 91 - 120 -- Alphabetically Arranged 2 I. NORTH COAST PRESSES DEL NORTE COUNTY. CRESCENT CITY. ARTS-IN-CORRECTIONS PROGRAM (Crescent City). The Brief Pelican: Anthology of Prison Writing, 1993. 1992 Pelikanesis: Creative Writing Anthology, 1994. 1994 Virtual Pelican: anthology of writing by inmates from Pelican Bay State Prison. -

Milch Galleries

THE MILCH GALLERIES YORK THE MILCH GALLERIES IMPORTANT WORKS IN PAINTINGS AND SCULPTURE BY LEADING AMERICAN ARTISTS 108 WEST 57TH STREET NEW YORK CITY Edition limited to One Thousand copies This copy is No 1 his Booklet is the second of a series we have published which deal only with a selected few of the many prominent American artists whose work is always on view in our Galleries. MILCH BUILDING I08 WEST 57TH STREET FOREWORD This little booklet, similar in character to the one we pub lished last year, deals with another group of painters and sculp tors, the excellence of whose work has placed them m the front rank of contemporary American art. They represent differen tendencies, every one of them accentuating some particular point of view and trying to find a personal expression for personal emotions. Emile Zola's definition of art as "nature seen through a temperament" may not be a complete and final answer to the age-old question "What is art?»-still it is one of the best definitions so far advanced. After all, the enchantment of art is, to a large extent, synonymous with the magnetism and charm of personality, and those who adorn their homes with paintings, etchings and sculptures of quality do more than beautify heir dwelling places. They surround themselves with manifestation of creative minds, with clarified and visualized emotions that tend to lift human life to a higher plane. _ Development of love for the beautiful enriches the resources of happiness of the individual. And the welfare of nations is built on no stronger foundation than on the happiness of its individual members. -

SFU Thesis Template Files

Promoting Women’s Awareness Towards Change in Nigeria: The Role of Literature by Lucia Emem-Obong Inyang B.A. (Hons.), University of Jos, 2011 Extended Essay Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the School of Communication (Dual Degree Program in Global Communication) Faculty of Communication, Art and Technology Lucia Emem-Obong Inyang 2015 SIMON FRASER UNIVERSITY Summer 2015 Approval Name: Emem-Obong Lucia Inyang Degree: Master of Arts (Communication) Title: Promoting Women’s Awareness towards Change in Nigeria: the Role of Literature Supervisory Committee: Program Director: Yuezhi Zhao Professor Katherine Reilly Senior Supervisor Assistant Professor Zhou Kui Senior Supervisor Associate Professor The Institute of Communication Studies Communication University of China Date Defended/Approved: August 7, 2015 ii Abstract This paper examines women’s struggle to overcome marginalization in a sexist and a patriarchal Nigerian society. It argues that fictional literature can be an effective tool for creating awareness, learning and dialogue among Nigerian women from various cultural, religious and ethnic background towards transformation. Literature, like any medium of communication, can be used to mobilize social change. This argument is illustrated through a literary analysis of three novels by three renowned female Nigerian writers: Efuru (1966) by Flora Nwapa, Second Class Citizen (1974) by Buchi Emecheta and Purple Hibiscus (2003) by Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie. The authors project womanhood in a positive light, upholding the potentials of women by making role models out of each female protagonist. Women’s efforts to free themselves from the bondage of tradition, politics, marriage and most importantly male dominance are what makes these three novels extremely powerful.