Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881 - 1973)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paintings by John W. Alexander ; Sculpture by Chester Beach

SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, DECEMBER 12 1916 TO JANUARY 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE 0 SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS OF WORK BY THE FOLLOWING ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO DEC. 12, 1916 TO JAN. 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN WHITE ALEXANDER OHN vV. ALEXANDER. Born, Pittsburgh, J Pennsylvania, 1856. Died, New York, May 31, 1915. Studied at the Royal Academy, Munich, and with Frank Duveneck. Societaire of Societe Nationale des Beaux Arts, Paris; Member of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, London; Societe Nouvelle, Paris ; Societaire of the Royal Society of Fine Arts, Brussels; President of the National Academy of Design, New York; President of the Natiomrl Academy Association; President of the National Society of Mural Painters, New York; Ex- President of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, New York; American Academy of Arts and Letters; Vice-President of the National Fine Arts Federation, Washington, D. C.; Member of the Architectural League, Fine Arts Federation and Fine Arts Society, New York; Honorary Member of the Secession Society, Munich, and of the Secession Society, Vienna; Hon- orary Member of the Royal Society of British Artists, of the American Institute of Architects and of the New York Society of Illustrators; President of the School Art League, New York; Trustee of the New York Public Library; Ex-President of the MacDowell Club, New York; Trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Trustee of the American Academy in Rome; Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, France; Honorary Degree of Master of Arts, Princeton University, 1892, and of Doctor of Literature, Princeton, 1909. -

Milch Galleries

THE MILCH GALLERIES YORK THE MILCH GALLERIES IMPORTANT WORKS IN PAINTINGS AND SCULPTURE BY LEADING AMERICAN ARTISTS 108 WEST 57TH STREET NEW YORK CITY Edition limited to One Thousand copies This copy is No 1 his Booklet is the second of a series we have published which deal only with a selected few of the many prominent American artists whose work is always on view in our Galleries. MILCH BUILDING I08 WEST 57TH STREET FOREWORD This little booklet, similar in character to the one we pub lished last year, deals with another group of painters and sculp tors, the excellence of whose work has placed them m the front rank of contemporary American art. They represent differen tendencies, every one of them accentuating some particular point of view and trying to find a personal expression for personal emotions. Emile Zola's definition of art as "nature seen through a temperament" may not be a complete and final answer to the age-old question "What is art?»-still it is one of the best definitions so far advanced. After all, the enchantment of art is, to a large extent, synonymous with the magnetism and charm of personality, and those who adorn their homes with paintings, etchings and sculptures of quality do more than beautify heir dwelling places. They surround themselves with manifestation of creative minds, with clarified and visualized emotions that tend to lift human life to a higher plane. _ Development of love for the beautiful enriches the resources of happiness of the individual. And the welfare of nations is built on no stronger foundation than on the happiness of its individual members. -

Michael Cowan Fitzgerald

1 Michael C. FitzGerald Office: 113 Hallden Hall tel. 860-297-2503 [email protected] [email protected] (home) EDUCATION 1976-1987 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Ph.D., M.Phil., M.A. DISSERTATION: "Pablo Picasso's Monument to Guillaume Apollinaire: Surrealism and Monumental Sculpture in France, 1918-1959." 1984-1986 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS M.B.A. 1972-1976 STANFORD UNIVERSITY B.A. EMPLOYMENT TRINITY COLLEGE (Hartford, CT) DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS 2007- Professor 2OO2-5 Director, Art History Program (first appointment) 1994-2007 Associate Professor, Department of Fine Arts 1996-1998 Chairman 1988-1994 Assistant Professor 1986-1988 CHRISTIE, MANSON AND WOODS INTERNATIONAL (New York, NY) Specialist-in-charge of Drawings, Department of Impressionist and Modern Art 1981-1983 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY (New York, NY) Preceptor,Department of Art History and Archaeology CONSULTANCY Research Director, Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz- Picasso para el Arte (FABA), 2020- AWARDS American Academy in Rome, April 2020 (deferred due to Corona Virus) Terra Foundation, 2006 2 National Endowment for the Arts, 2005-06 Faculty Research Leave, Trinity College, 2001-2002 3-Year Expense Grant, Trinity College, 2001-2004 Archives Grant, New York State Council of the Arts, 1999-2000 (with Whitney Museum of American Art) Fellowship, National Endowment for the Humanities, 1994-95 Faculty Research Grant, Trinity College, Summer 1993 Travel to Collections Grant, National Endowment for the Humanities, Summer 1991 Faculty Research Grant, Trinity College, Summer l989 Rudolf Wittkower Fellowship, Columbia University, 1980-81 Travel Grant, Columbia University, Summer l982; President's Fellowship, Columbia University, l977-78 CURRENT PROJECT Curator, Picasso and Classcial Traditions, This exhibition is a collaboration between the Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla and the Museo Picasso Málaga. -

Pablo Picasso, Published by Christian Zervos, Which Places the Painter of the Demoiselles Davignon in the Context of His Own Work

PRESS KIT PICASSO 1932 Exhibition 10 October 2017 to 11 February 2018 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE En partenariat avec Exposition réalisée grâce au soutien de 2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE From 10 October to the 11 February 2018 at Musée national Picasso-Paris The first exhibition dedicated to the work of an artist from January 1 to December 31, the exhibition Picasso 1932 will present essential masterpieces in Picassos career as Le Rêve (oil on canvas, private collection) and numerous archival documents that place the creations of this year in their context. This event, organized in partnership with the Tate Modern in London, invites the visitor to follow the production of a particularly rich year in a rigorously chronological journey. It will question the famous formula of the artist, according to which the work that is done is a way of keeping his journal? which implies the idea of a coincidence between life and creation. Among the milestones of this exceptional year are the series of bathers and the colorful portraits and compositions around the figure of Marie-Thérèse Walter, posing the question of his works relationship to surrealism. In parallel with these sensual and erotic works, the artist returns to the theme of the Crucifixion while Brassaï realizes in December a photographic reportage in his workshop of Boisgeloup. 1932 also saw the museification of Picassos work through the organization of retrospectives at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris and at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which exhibited the Spanish painter to the public and critics for the first time since 1911. The year also marked the publication of the first volume of the Catalog raisonné of the work of Pablo Picasso, published by Christian Zervos, which places the painter of the Demoiselles dAvignon in the context of his own work. -

Museu Picasso Presents Picasso/Dalí, Dalí/Picasso, the First Exhibition to Explore the Relationship Between Both Artists

Press Release THE MUSEU PICASSO PRESENTS PICASSO/DALÍ, DALÍ/PICASSO, THE FIRST EXHIBITION TO EXPLORE THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BOTH ARTISTS Organised by the Museu Picasso with The Dalí Museum in Saint Petersburg, Florida, in collaboration with the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí in Figueres, this show examines the relationship between Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí—one of the most decisive crossroads in the history of 20th-century art Dalí felt admiration for Picasso dating back to before they had even met, when the young Dalí was making his first avant-garde forays in the early 1920’s The show includes works rarely seen in Europe, including Salvador Dalí’s Portrait of My Sister and Profanation of the Host, and 29 pieces by the two artists that will only be seen in Barcelona Barcelona, 19 March 2015. The Museu Picasso and The Dalí Museum in Saint Petersburg, Florida, have worked with the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí in Figueres and more than 25 art museums and private collectors worldwide to put on the first exhibition to analyse the relationship between Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí. The show sheds light on their highly productive relationship and reveals its high points and contradictions. “We didn’t set out to show that these two artists are in some way similar, but to help visitors get a better understanding of them,” says the show’s co-curator, William Jeffett, from The Dalí Museum. The idea is to let visitors see work by both artists in a fresh light by showing where their paths crossed. The exhibition reveals that after Dalí visited Picasso at his studio in Paris, his work underwent a tremendous experimental shift: he quickly went from merely “analysing” Picasso’s work to fashioning his own, fully Surrealist artistic language. -

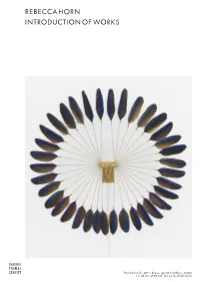

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). -

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity the Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010

Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity The Museum of Modern Art, New York November 08, 2009-January 25, 2010 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Upholstery, drapery, and wall-covering samples 1923-29 Wool, rayon, cotton, linen, raffia, cellophane, and chenille Between 8 1/8 x 3 1/2" (20.6 x 8.9 cm) and 4 3/8 x 16" (11.1 x 40.6 cm) The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the designer or Gift of Josef Albers ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Silk, cotton, and acetate 57 1/8 x 36 1/4" (145 x 92 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1925 Wool and silk 7' 8 7.8" x 37 3.4" (236 x 96 cm) Die Neue Sammlung - The International Design Museum Munich ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Wall hanging 1926 Silk (three-ply weave) 70 3/8 x 46 3/8" (178.8 x 117.8 cm) Harvard Art Museum, Busch-Reisinger Museum. Association Fund Bauhaus 1919 - 1933: Workshops for Modernity - Exhibition Checklist 10/27/2009 Page 1 of 80 ANNI ALBERS German, 1899-1994; at Bauhaus 1922–31 Tablecloth Fabric Sample 1930 Mercerized cotton 23 3/8 x 28 1/2" (59.3 x 72.4 cm) Manufacturer: Deutsche Werkstaetten GmbH, Hellerau, Germany The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Purchase Fund JOSEF ALBERS German, 1888-1976; at Bauhaus 1920–33 Gitterbild I (Grid Picture I; also known as Scherbe ins Gitterbild [Glass fragments in grid picture]) c. -

Eduardo Chillida

Press Release Eduardo Chillida Hauser & Wirth New York, 69th Street 30 April – 27 July 2018 Private view: Monday 30 April, 6 – 8 pm The bird is one of the signs of space, each one of Chillida’s sculptures represents, much like the bird, a sign of space; each one of them says a different thing: the iron says wind, the wood says song, the alabaster says light yet they all say the same thing: space. A rumor of limits, a coarse song; the wind, an ancient name of the spirit, blows and spins tirelessly in the house of space. – Octavio Paz New York… Hauser & Wirth is pleased to present its inaugural exhibition of works by Eduardo Chillida (1924 – 2002), Spain’s foremost sculptor of the twentieth century. Widely recognized for monumental iron and steel public sculptures displayed across the globe, Chillida is also celebrated for a wholly distinctive use of materials such as stone, chamotte clay, and paper to engage concerns both earthly and metaphysical. On view from 30 April through 27 July 2018, this exhibition showcases the artist’s varied and innovative practice through a focused presentation of rarely displayed works, including small-scale sculptures, collages, drawings, and artist books that shed new light on Chillida’s enduring fascination with space and organic form. Originally a student of architecture in Madrid, Chillida created art guided by its principles; his early interest in the field had a lasting impact on his development as an artist, shaping his understanding of spatial relationships and sparking what would become a deep-rooted interest in making space visible through a consideration of the forms surrounding it. -

1947 Drops out of Architecture School to Study Drawing at the Círculo De Bellas Artes in Madrid. Works in José Martínez Repul

1947 Drops out of architecture school to study drawing at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid. Works in José Martínez Repullés's sculpture studio, where he creates his first sculpture. 1948 Moves to Paris, where he forges a friendship with artist Pablo Palazuelo. 1949 Participates in the Salon de Mai in Paris. 1950 Takes part in the exhibition Les mains éblouiesat Galerie Maeght in Paris. Marries Pilar Belzunce. 1951 Returns to the Spanish province of Guipúzcoa, settling in Hernani. Creates his first work in bronze. 1954 Has his first solo exhibition in Spain, at Galería Clan in Madrid. Creates four doors for the Basílica Nuestra Señora de Aránzazu in Oñate, Spain. 1955 The Kunsthalle Bern presents an exhibition of his work. 1956 Exhibits at Galerie Maeght in Paris. 1958 Receives the International Grand Prize for Sculpture at the XXIX Biennale di Venezia. Chillida's work is featured in Sculpture and Drawings from Seven Sculptors at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Receives the Graham Foundation Award and exhibits at the Graham Foundation in Chicago. 1959 Participates in Documenta 2 in Kassel, Germany. Creates his first etchings, first works in wood, and first works in steel. 1960 Receives the Kandinsky Prize, awarded by the “ArtChronika” Cultural Fund. Forges a friendship with sculptor Alberto Giacometti. 1961 Exhibits at Galerie Maeght in Paris. 1964 Receives the Carnegie Prize, awarded by the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. 1965 Exhibits at Tunnard Gallery in London and the Kestnergesellschaft Hannover. 1966 The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston organizes a retrospective exhibition of Chillida's work. -

Teachers' Resource

TEACHERS’ RESOURCE BECOMING PICASSO: PARIS 1901 CONTENTS 1: INTRODUCTION TO THE EXHIBITION 2: ‘I WAS A PAINTER AND I BECAME PICASSO’ 3:THE ARTIST AS OUTSIDER: THE HARLEQUIN IN PICASSO’S EARLY WORK 4: PAINTING LIFE AND DEATH: PICASSO’S SECULAR ALTARPIECE 5: THE SECRET LIFE OF A PAINTING 6: PAINTING THE FIGURE: A CONTEMPORARY PRACTICE PERSPECTIVE 7: PICASSO’S BELLE ÉPOQUE: A SUBVERSIVE APPROACH TO STYLE AND SUBJECT 8: GLOSSARY 9: TEACHING RESOURCE CD TEACHERS’ RESOURCE BECOMING PICASSO: PARIS 1901 Compiled and produced by Sarah Green Design by Joff Whitten SUGGESTED CURRICULUM LINKS FOR EACH ESSAY ARE MARKED IN ORANGE TERMS REFERRED TO IN THE GLOSSARY ARE MARKED IN PURPLE To book a visit to the gallery or to discuss any of the education projects at The Courtauld Gallery please contact: e: [email protected] t: 0207 848 1058 Cover image: Pablo Picasso Child with a Dove, 1901 Oil on canvas 73 x 54 cm Private collection © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2013 This page: Pablo Picasso Dwarf-Dancer, 1901 Oil on board 105 x 60 cm Museu Picasso, Barcelona (gasull Fotografia) © Succession Picasso/DACS, London 2013 WELCOME The Courtauld is a vibrant international centre for the study of the history of art and conservation and is also home to one of the finest small art museums in the world. The Public Programmes department runs an exceptional programme of activities suitable for young people, school teachers and members of the public, whatever their age or background. We offer resources which contribute to the understanding, knowledge and enjoyment of art history based upon the world-renowned art collection and the expertise of our students and scholars. -

Autumn 2020 FILM and TELEVISION DEALS Spellslinger Series – Sebastien De Castell Marge in Charge Series – Isla Fisher We Were Liars – E

Rights Guide Autumn 2020 FILM AND TELEVISION DEALS Spellslinger series – Sebastien de Castell Marge in Charge series – Isla Fisher We Were Liars – E. Lockhart Love Letters to the Dead – Ava Dellaira Cell 7 – Kerry Drewery CONTENTS Our Chemical Hearts – Krystal Sutherland Frogkisser! – Garth Nix YOUNG ADULT 4 S.T.A.G.S. – M. A. Bennett TEEN 14 The Cruel Prince (Folk of the Air) series – Holly Black NINE TO TWELVE 21 Charlie and Me – Mark Lowery ILLUSTRATED FICTION 30 The Boy Who Grew Dragons – Andy Shepherd PICTURE BOOKS 38 The Girl Who Drank the Moon – Kelly Barnhill ANTHOLOGY 40 Iremonger series - Heap House, Foulsham, Lungdon – Edward Carey NON-FICTION 41 Birdy – Jess Vallance BACKLIST 46 Stepsister – Jennifer Donnelly Genuine Fraud – E. Lockhart The Wild Robot – Peter Brown Enola Holmes – Nancy Springer 36 Questions That Changed My Mind About You – Vicki Grant The Ghost Bride – Yangsze Choo The Last Human – Lee Bacon The Distance Between Me and the Cherry Tree – Paola Peretti With the Fire on High – Elizabeth Acevedo The Witch’s Boy – Kelly Barnhill The Tattooist of Auschwitz – Heather Morris The Red Ribbon – Lucy Adlington The Old Kingdom series – Garth Nix Perfectly Preventable Deaths – Deirdre Sullivan A Semi-Definitive List of Worst Nightmares – Krystal Sutherland The Keys to the Kingdom series – Garth Nix Night Shift - Debi Gliori 3 YOUNG ADULT YOUNG ADULT Chris Whitaker Yasmin Rahman THE FOREVERS THIS IS MY TRUTH What would you do if you could get There are some secrets that even best away with anything? friends don’t tell each other . They called it Selena. -

Picasso, Theatre and the Monument to Apollinaire

PICASSO, THEATRE AND THE MONUMENT TO APOLLINAIRE John Finlay • Colloque Picasso Sculptures • 24 mars 2016 n his programme note for Parade (1917), Guil- Ilaume Apollinaire made special mention of “the fantastic constructions representing the gigantic and surprising figures of the Managers” (fig. 1). The poet reflected, “Picasso’s Cubist costumes and scenery bear tall superstructures knowingly created a conflict witness to the realism of his art. This realism—or Cub- between the vitality of dance and the immobility of ism, if you will—is the influence that has most stirred more grounded sculptures. As a practical and sym- the arts over the past ten years.”1 Apollinaire’s note bolic feature, the Managers anticipate certain aspects acknowledges a number of important things regard- of Picasso’s later sculpture. ing Picasso’s new theatrical venture. Most notable is The decors for the ballet (1924) were equally “sur- his recognition that the Managers are not costumes real”, contemporary forms of sculpture. Picasso made in the traditional sense, but three-dimensional in allowance for mobility in his set designs by enabling conception, and linked with his earlier Cubist work. the assembled stage props (even the stars) to move In describing the Managers as “construction”, Apol- in time to the music, the dancers manipulating them linaire was perhaps thinking of Picasso’s satirical Gui- like secateurs. For the Three Graces, Picasso created tar Player at a Café Table (fig. 2). The assemblage ran wickerwork constructions manipulated like puppets the gamut from a Cubist painting on a flat surface, by wires. The “practicables” were similar to telephone showing a harlequin with pasted paper arms, to a extension cables that expanded and contracted as real guitar suspended from strings, to a still life on a their heads bounced up and down.