Teachers' Resource

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Objects Proposed for Protection Under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (Protection of Cultural Objects on Loan)

List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Picasso and Paper 25 January 2020 to 13 April 2020 Arist: Pablo Picasso Title: Self-portrait Date: 1918-1920 Medium: Graphite on watermarked laid paper (with LI countermark) Size: 32 x 21.5 cm Accession: n°00776 Lender: BRUSSELS, FUNDACIÓN ALMINE Y BERNARD RUIZ-PICASSO PARA EL ARTE 20 rue de l'Abbaye Bruxelles 1050 Belgique © FABA Photo: Marc Domage PROVENANCE Donation by Bernard Ruiz-Picasso; estate of the artist; previously remained in the possession of the artist until his death, 1973 Note that: This object has a complete provenance for the years 1933-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Picasso and Paper 25 January 2020 to 13 April 2020 Arist: Pablo Picasso Title: Mother with a Child Sitting on her Lap Date: December 1947 Medium: Pastel and graphite on Arches-like vellum (with irregular pattern). Invitation card printed on the back Size: 13.8 x 10 cm Accession: n°11684 Lender: BRUSSELS, FUNDACIÓN ALMINE Y BERNARD RUIZ-PICASSO PARA EL ARTE 20 rue de l'Abbaye Bruxelles 1050 Belgique © FABA Photo: Marc Domage PROVENANCE Donation by Bernard Ruiz-Picasso; Estate of the artist; previously remained in the possession of the artist until his death, 1973 Note that: This object was made post-1945 List of objects proposed for protection under Part 6 of the Tribunals, Courts and Enforcement Act 2007 (protection of cultural objects on loan) Picasso and Paper 25 January 2020 to 13 April 2020 Arist: Pablo Picasso Title: Little Girl Date: December 1947 Medium: Pastel and graphite on Arches-like vellum. -

Famous Paintings of Picasso Guernica

Picasso ArtStart – 7 Dr. Hyacinth Paul https://www.hyacinthpaulart.com/ The genius of Picasso • Picasso was a cubist and known for painting, drawing, sculpture, stage design and writing. • He developed cubism along with Georges Braque • Born 25th Oct 1881 in Malaga, Spain • Spent time in Spain and France. • Died in France 8th April, 1973, Age 91 Painting education • Trained by his father at age 7 • Attended the School of Fine Arts, Barcelona • 1897, attended Madrid's Real Academia de Bellas Artes, He preferred to study the paintings of Rembrandt, El Greco, Goya and Velasquez • 1901-1904 – Blue period; 1904-1906 Pink period; 1907- 1909 – African influence 1907-1912 – Analytic Cubism; 1912-1919 - Synthetic Cubism; 1919-1929 - Neoclacissism & Surrealism • One of the greatest influencer of 20th century art. Famous paintings of Picasso Family of Saltimbanques - (1905) – National Gallery of Art , DC Famous paintings of Picasso Boy with a Pipe – (1905) – (Private collection) Famous paintings of Picasso Girl before a mirror – (1932) MOMA, NYC Famous paintings of Picasso La Vie (1903) Cleveland Museum of Art, OH Famous paintings of Picasso Le Reve – (1932) – (Private Collection Steven Cohen) Famous paintings of Picasso The Young Ladies of Avignon – (1907) MOMA, NYC Famous paintings of Picasso Ma Jolie (1911-12) Museum of Modern Art, NYC Famous paintings of Picasso The Old Guitarist (1903-04) - The Art Institute of Chicago, IL Famous paintings of Picasso Guernica - (1937) – (Reina Sofia, Madrid) Famous paintings of Picasso Three Musicians – (1921) -

La Estafa En La Obra De Arte

UNIVERSIDAD DE MURCIA DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA JUR´IDICA Y CIENCIAS PENALES Y CRIMINOLOGICAS´ La Estafa en la Obra de Arte D~na.Mar´ıa Angeles´ Casab´oOrt´ı 2014 Dedicatorias En este trabajo de investigaci´onme parece obligado hacer un previo reconocimiento a todas aquellas personas que me han prestado su ayuda e inmejorables consejos. Al Profesor Jaime Peris por su apoyo, la paciente orientaci´one in- estimables sugerencias a trav´esde todas las etapas del proceso. Su supervisi´ony opiniones me recordaron que los conocimientos pluridis- ciplinares enriquecen cualquier investigaci´on. Al Profesor Amadeo Serra por su constante seguimiento y relevantes aportes, compartiendo su tiempo de manera generosa. Sus interesantes clases fueron un ejemplo de como realizar siempre un trabajo riguroso. A Ana Rosa G´omezCalvet por su colaboraci´onen la maquetaci´ony revisi´on. A mi madre y hermana Luc´ıa,con las que he podido compartir esta pasi´on. A la memoria de mi padre que me transmiti´oel amor por el derecho. A Roberto y mis hijas Bertha y Angela,´ que me han acompa~nadoen este viaje y que me hacen feliz. Resumen El prop´ositode la presente tesis es el an´alisisy estudio jur´ıdicopenal en torno a la estafa mediante obras de arte falsas. El objeto de la investigaci´on,pues, queda circunscrito a la figura b´asicadel delito de estafa y a los preceptos que la complementan recogidos en los art´ıculos 248.1, 249 y 623,4 del C´odigoPenal. El n´ucleode la tesis est´aformado por tres cap´ıtulos,en un primero, se realiza un estudio terminol´ogico,necesario para definir un marco introductorio donde se acota el tema: el mercado del arte y el concepto de obra de arte. -

Senior 1 Art. Interim Guide. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 375 054 SO 024 441 AUTHOR Hartley, Michael, Ed. TITLE Senior 1 Art. Interim Guide. INSTITUTION Manitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg. REPORT NO ISBN-0-7711-1162-2 PUB DATE 93 NOTE 201p.; Photographs might not produce well. AVAILABLE FROMManitoba Dept. of Education and Training, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada. PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use Teaching Guides (For Teacher)(052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC09 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Art Activities; Art Appreciation; Art Criticism; *Art Education; Course Content; Curriculum Guides; Foreign Countries; Grade 9; High Schools; *Secondary School Curriculum IDENTIFIERS Manitoba ABSTRACT This Manitoba, Canada curriculum guide presents an art program that effectively bridges Canadian junior and senior high school art levels. Content areas include media and techniques, history and culture, criticism and appreciation, and design. Four core units present fundamental art knowledge through themes based on self and environmental exploration. Media and techniques used include drawing, collage, sculpture and ceramics. Four secondary units are enrichment oriented. Maskmaking expands on self-exploration by examining different faces humans present to establish identity and communication. Mass media introduces students to concepts of advertisement communication. Differences between need and want are explored. Landscape is studied as interpretations of environment as seen, remembered, or imagined. Investigation of the future allows for exploration of various scenarios with a wide variety of materials. The teaching method employed is problem solving/inquiry. Idea journals and portfolios are identified and used as evaluation tools. Appendices and bibliographies are included. (MM) ********************************************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made from the original document. *********************************************************************** 1993 Senior I Art U S. -

Press Information

PRESS INFORMATION PICASSO IN ISTANBUL SAKIP SABANCI MUSEUM, ISTANBUL 24 November 2005 to 26 March 2006 Press enquiries: Erica Bolton and Jane Quinn 10 Pottery Lane London W11 4LZ Tel: 020 7221 5000 Fax: 020 7221 8100 [email protected] Contents Press Release Chronology Complete list of works Biographies 1 Press Release Issue: 22 November 2005 FIRST PICASSO EXHIBITION IN TURKEY IS SELECTED BY THE ARTIST’S GRANDSON Picasso in Istanbul, the first major exhibition of works by Pablo Picasso to be staged in Turkey, as well as the first Turkish show to be devoted to a single western artist, will go on show at the Sakip Sabanci Museum in Istanbul from 24 November 2005 to 26 March 2006. Picasso in Istanbul has been selected by the artist‟s grandson Bernard Ruiz-Picasso and Marta-Volga Guezala. Picasso expert Marilyn McCully and author Michael Raeburn are joint curators of the exhibition and the catalogue, working together with Nazan Olçer, Director of the Sakip Sabanci Museum, and Selmin Kangal, the museum‟s Exhibitions Manager. The exhibition will include 135 works spanning the whole of the artist‟s career, including paintings, sculptures, ceramics, textiles and photographs. The works have been loaned from private collections and major museums, including the Picasso museums in Barcelona and Paris. The exhibition also includes significant loans from the Fundaciñn Almine y Bernard Ruiz-Picasso para el Arte. A number of rarely seen works from private collections will be a special highlight of the exhibition, including tapestries of “Les Demoiselles d‟Avignon” and “Les femmes à leur toilette” and the unique bronze cast, “Head of a Warrior, 1933”. -

Picasso Et La Famille 27-09-2019 > 06-01-2020

Picasso et la famille 27-09-2019 > 06-01-2020 1 Cette exposition est organisée par le Musée Sursock avec le soutien exceptionnel du Musée national Picasso-Paris dans le cadre de « Picasso-Méditerranée », et avec la collaboration du Ministère libanais de la Culture. Avec la généreuse contribution de Danièle Edgar de Picciotto et le soutien de Cyril Karaoglan. Commissaires de l’exposition : Camille Frasca et Yasmine Chemali Scénographie : Jacques Aboukhaled Graphisme de l’exposition : Mind the gap Éclairage : Joe Nacouzi Graphisme de la publication et photogravure : Mind the gap Impression : Byblos Printing Avec la contribution de : Tinol Picasso-Méditerranée, une initiative du Musée national Picasso-Paris « Picasso-Méditerranée » est une manifestation culturelle internationale qui se tient de 2017 à 2019. Plus de soixante-dix institutions ont imaginé ensemble une programmation autour de l’oeuvre « obstinément méditerranéenne » de Pablo Picasso. À l’initiative du Musée national Picasso-Paris, ce parcours dans la création de l’artiste et dans les lieux qui l’ont inspiré offre une expérience culturelle inédite, souhaitant resserrer les liens entre toutes les rives. Maternité, Mougins, 30 août 1971 Huile sur toile, 162 × 130 cm Musée national Picasso-Paris. Dation Pablo Picasso, 1979. MP226 © RMN-Grand Palais / Adrien Didierjean © Succession Picasso 2019 L’exposition Picasso et la famille explore les rapports de Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) à la notion de noyau familial, depuis la maternité jusqu’aux jeux enfantins, depuis l’image d’une intimité conceptuelle à l’expérience multiple d’une paternité sous les feux des projecteurs. Réunissant dessins, gravures, peintures et sculptures, l’exposition survole soixante-dix-sept ans de création, entre 1895 et 1972, au travers d’une sélection d’œuvres marquant des points d’orgue dans la longue vie familiale et sentimentale de l’artiste et dont la variété des formes illustre la réinvention constante du vocabulaire artistique de Picasso. -

Michael Cowan Fitzgerald

1 Michael C. FitzGerald Office: 113 Hallden Hall tel. 860-297-2503 [email protected] [email protected] (home) EDUCATION 1976-1987 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF ARTS AND SCIENCES Ph.D., M.Phil., M.A. DISSERTATION: "Pablo Picasso's Monument to Guillaume Apollinaire: Surrealism and Monumental Sculpture in France, 1918-1959." 1984-1986 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL OF BUSINESS M.B.A. 1972-1976 STANFORD UNIVERSITY B.A. EMPLOYMENT TRINITY COLLEGE (Hartford, CT) DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS 2007- Professor 2OO2-5 Director, Art History Program (first appointment) 1994-2007 Associate Professor, Department of Fine Arts 1996-1998 Chairman 1988-1994 Assistant Professor 1986-1988 CHRISTIE, MANSON AND WOODS INTERNATIONAL (New York, NY) Specialist-in-charge of Drawings, Department of Impressionist and Modern Art 1981-1983 COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY (New York, NY) Preceptor,Department of Art History and Archaeology CONSULTANCY Research Director, Fundación Almine y Bernard Ruiz- Picasso para el Arte (FABA), 2020- AWARDS American Academy in Rome, April 2020 (deferred due to Corona Virus) Terra Foundation, 2006 2 National Endowment for the Arts, 2005-06 Faculty Research Leave, Trinity College, 2001-2002 3-Year Expense Grant, Trinity College, 2001-2004 Archives Grant, New York State Council of the Arts, 1999-2000 (with Whitney Museum of American Art) Fellowship, National Endowment for the Humanities, 1994-95 Faculty Research Grant, Trinity College, Summer 1993 Travel to Collections Grant, National Endowment for the Humanities, Summer 1991 Faculty Research Grant, Trinity College, Summer l989 Rudolf Wittkower Fellowship, Columbia University, 1980-81 Travel Grant, Columbia University, Summer l982; President's Fellowship, Columbia University, l977-78 CURRENT PROJECT Curator, Picasso and Classcial Traditions, This exhibition is a collaboration between the Museo de Bellas Artes de Sevilla and the Museo Picasso Málaga. -

Pablo Picasso, Published by Christian Zervos, Which Places the Painter of the Demoiselles Davignon in the Context of His Own Work

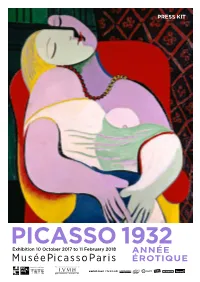

PRESS KIT PICASSO 1932 Exhibition 10 October 2017 to 11 February 2018 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE En partenariat avec Exposition réalisée grâce au soutien de 2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE From 10 October to the 11 February 2018 at Musée national Picasso-Paris The first exhibition dedicated to the work of an artist from January 1 to December 31, the exhibition Picasso 1932 will present essential masterpieces in Picassos career as Le Rêve (oil on canvas, private collection) and numerous archival documents that place the creations of this year in their context. This event, organized in partnership with the Tate Modern in London, invites the visitor to follow the production of a particularly rich year in a rigorously chronological journey. It will question the famous formula of the artist, according to which the work that is done is a way of keeping his journal? which implies the idea of a coincidence between life and creation. Among the milestones of this exceptional year are the series of bathers and the colorful portraits and compositions around the figure of Marie-Thérèse Walter, posing the question of his works relationship to surrealism. In parallel with these sensual and erotic works, the artist returns to the theme of the Crucifixion while Brassaï realizes in December a photographic reportage in his workshop of Boisgeloup. 1932 also saw the museification of Picassos work through the organization of retrospectives at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris and at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which exhibited the Spanish painter to the public and critics for the first time since 1911. The year also marked the publication of the first volume of the Catalog raisonné of the work of Pablo Picasso, published by Christian Zervos, which places the painter of the Demoiselles dAvignon in the context of his own work. -

Press Dossier

KEES VAN DONGEN From 11th June to 27th September 2009 PRESS CONFERENCE 11th June 2009, at 11.30 a.m. INAUGURATION 11th June 2009, at 19.30 p.m. Press contact: Phone: + 34 93 256 30 21 /26 Fax: + 34 93 315 01 02 [email protected] CONTENTS 1. PRESENTATION 2. EXHIBITION TOUR 3. EXHIBITION AREAS 4. EXTENDED LABELS ON WORKS 5. CHRONOLOGY 1. PRESENTATION This exhibition dedicated to Kees Van Dongen shows the artist‘s evolution from his student years to the peak of his career and evokes many of his aesthetic ties and exchanges with Picasso, with whom he temporarily shared the Bateau-Lavoir. Born in a suburb of Rotterdam, Van Dongen‘s career was spent mainly in Paris where he came to live in 1897. A hedonist and frequent traveller, he was a regular visitor to the seaside resorts of Deauville, Cannes and Monte Carlo, where he died in 1968. Van Dongen experienced poverty, during the years of revelry with Picasso, and then fame before finally falling out of fashion, a status he endured with a certain melancholy. The exhibition confirms Kees Van Dongen‘s decisive role in the great artistic upheavals of the early 20th century as a member of the Fauvist movement, in which he occupied the unique position of an often irreverent and acerbic portraitist. The virulence and extravagance of his canvases provoked immediate repercussions abroad, particularly within the Die Brücke German expressionist movement. Together with his orientalism, contemporary with that of Matisse, this places Van Dongen at the very forefront of the avant-garde. -

Museu Picasso Presents Picasso/Dalí, Dalí/Picasso, the First Exhibition to Explore the Relationship Between Both Artists

Press Release THE MUSEU PICASSO PRESENTS PICASSO/DALÍ, DALÍ/PICASSO, THE FIRST EXHIBITION TO EXPLORE THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN BOTH ARTISTS Organised by the Museu Picasso with The Dalí Museum in Saint Petersburg, Florida, in collaboration with the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí in Figueres, this show examines the relationship between Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí—one of the most decisive crossroads in the history of 20th-century art Dalí felt admiration for Picasso dating back to before they had even met, when the young Dalí was making his first avant-garde forays in the early 1920’s The show includes works rarely seen in Europe, including Salvador Dalí’s Portrait of My Sister and Profanation of the Host, and 29 pieces by the two artists that will only be seen in Barcelona Barcelona, 19 March 2015. The Museu Picasso and The Dalí Museum in Saint Petersburg, Florida, have worked with the Fundació Gala-Salvador Dalí in Figueres and more than 25 art museums and private collectors worldwide to put on the first exhibition to analyse the relationship between Pablo Picasso and Salvador Dalí. The show sheds light on their highly productive relationship and reveals its high points and contradictions. “We didn’t set out to show that these two artists are in some way similar, but to help visitors get a better understanding of them,” says the show’s co-curator, William Jeffett, from The Dalí Museum. The idea is to let visitors see work by both artists in a fresh light by showing where their paths crossed. The exhibition reveals that after Dalí visited Picasso at his studio in Paris, his work underwent a tremendous experimental shift: he quickly went from merely “analysing” Picasso’s work to fashioning his own, fully Surrealist artistic language. -

Picasso בין השנים 1899-1955

http://www.artpane.com קטלוג ואלבום אמנות המתעד את עבודותיו הגרפיות )ליתוגרפיות, תחריטים, הדפסים וחיתוכי עץ( של פאבלו פיקאסו Pablo Picasso בין השנים 1899-1955. מבוא מאת ברנארד גיסר Bernhard Geiser בהוצאת Thames and Hudson 1966 אם ברצונכם בספר זה התקשרו ואשלח תיאור מפורט, מחיר, אמצעי תשלום ואפשרויות משלוח. Picasso - His graphic Work Volume 1 1899-1955 - Thames and Hudson 1966 http://www.artpane.com/Books/B1048.htm Contact me at the address below and I will send you further information including full description of the book and the embedded lithographs as well as price and estimated shipping cost. Contact Details: Dan Levy, 7 Ben Yehuda Street, Tel-Aviv 6248131, Israel, Tel: 972-(0)3-6041176 [email protected] Picasso - His graphic Work Volume 1 1899-1955 - Introduction by Bernhard Geiser Pablo Picasso When Picasso talks about his life - which is not often - it is mostly to recall a forgotten episode or a unique experience. It is not usual for him to dwell upon the past because he prefers to be engaged in the present: all his thoughts and aspirations spring from immediate experience. It is on his works - and not least his graphic work - therefore, that we should concentrate in order to learn most about him. A study of his etchings, lithographs, and woodcuts reveals him in the most personal and intimate aspect. I cannot have a print of his in my hand without feeling the artist’s presence, as if he himself were with me in the room, talking, laughing, revealing his joys and sufferings. Daniel Henry Kahnweiler once said: “With Picasso, art is never mere rhetoric, his work is inseparable from his life... -

RCEWA Case Xx

Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest: Note of case hearing on 18 July 2012: A painting by Pablo Picasso, Child with a Dove (Case 3, 2012-13) Application 1. The Reviewing Committee on the Export of Works of Art and Objects of Cultural Interest (RCEWA) met on 18 July 2012 to consider an application to export a painting by Pablo Picasso, Child with a Dove. The value shown on the export licence application was £50,000,000, which represented the sale price. The expert adviser had objected to the export of the painting under the first, second and third Waverly criteria i.e. on the grounds that it was so closely connected with our history and national life that its departure would be a misfortune, that it was of outstanding aesthetic importance and that it was of outstanding significance for the study of the birth of modernism and the reception of modernism in the UK. 2. The seven regular RCEWA members present were joined by three independent assessors, acting as temporary members of the Reviewing Committee. 3. The applicant confirmed that the value did include VAT and that VAT would be payable in the event of a UK sale. The applicant also confirmed that the owner understood the circumstances under which an export licence might be refused and that, if the decision on the licence was deferred, the owner would allow the painting to be displayed for fundraising. Expert’s submission 4. The expert had provided a written submission stating that the painting, Child with a Dove, was one of the earliest and most important works by Picasso to enter a British collection.