New York Times 7 November 2004 P. AR 23 up Close and Very Personal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Paintings by John W. Alexander ; Sculpture by Chester Beach

SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, DECEMBER 12 1916 TO JANUARY 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE 0 SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS OF WORK BY THE FOLLOWING ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO DEC. 12, 1916 TO JAN. 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN WHITE ALEXANDER OHN vV. ALEXANDER. Born, Pittsburgh, J Pennsylvania, 1856. Died, New York, May 31, 1915. Studied at the Royal Academy, Munich, and with Frank Duveneck. Societaire of Societe Nationale des Beaux Arts, Paris; Member of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, London; Societe Nouvelle, Paris ; Societaire of the Royal Society of Fine Arts, Brussels; President of the National Academy of Design, New York; President of the Natiomrl Academy Association; President of the National Society of Mural Painters, New York; Ex- President of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, New York; American Academy of Arts and Letters; Vice-President of the National Fine Arts Federation, Washington, D. C.; Member of the Architectural League, Fine Arts Federation and Fine Arts Society, New York; Honorary Member of the Secession Society, Munich, and of the Secession Society, Vienna; Hon- orary Member of the Royal Society of British Artists, of the American Institute of Architects and of the New York Society of Illustrators; President of the School Art League, New York; Trustee of the New York Public Library; Ex-President of the MacDowell Club, New York; Trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Trustee of the American Academy in Rome; Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, France; Honorary Degree of Master of Arts, Princeton University, 1892, and of Doctor of Literature, Princeton, 1909. -

Milch Galleries

THE MILCH GALLERIES YORK THE MILCH GALLERIES IMPORTANT WORKS IN PAINTINGS AND SCULPTURE BY LEADING AMERICAN ARTISTS 108 WEST 57TH STREET NEW YORK CITY Edition limited to One Thousand copies This copy is No 1 his Booklet is the second of a series we have published which deal only with a selected few of the many prominent American artists whose work is always on view in our Galleries. MILCH BUILDING I08 WEST 57TH STREET FOREWORD This little booklet, similar in character to the one we pub lished last year, deals with another group of painters and sculp tors, the excellence of whose work has placed them m the front rank of contemporary American art. They represent differen tendencies, every one of them accentuating some particular point of view and trying to find a personal expression for personal emotions. Emile Zola's definition of art as "nature seen through a temperament" may not be a complete and final answer to the age-old question "What is art?»-still it is one of the best definitions so far advanced. After all, the enchantment of art is, to a large extent, synonymous with the magnetism and charm of personality, and those who adorn their homes with paintings, etchings and sculptures of quality do more than beautify heir dwelling places. They surround themselves with manifestation of creative minds, with clarified and visualized emotions that tend to lift human life to a higher plane. _ Development of love for the beautiful enriches the resources of happiness of the individual. And the welfare of nations is built on no stronger foundation than on the happiness of its individual members. -

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881 - 1973)

Pablo Picasso (Spanish, 1881 - 1973) Pablo Picasso is considered to be the greatest artist of the 20th century, the Grand Master primo assoluto of Modernism, and a singular force whose work and discoveries in the realm of the visual have informed and influenced nearly every artist of the 20th century. It has often been said that an artist of Picasso’s genius only comes along every 500 years, and that he is the only artist of our time who stands up to comparison with da Vinci, Michelangelo, and Raphael – the grand triumvirate of the Italian Renaissance. Given Picasso’s forays into Symbolism, Primitivism, neo-Classicism, Surrealism, sculpture, collage, found-object art, printmaking, and post-WWII contemporary art, art history generally regards his pioneering of Cubism to have been his landmark achievement in visual phenomenology. With Cubism, we have, for the first time, pictorial art on a two-dimensional surface (paper or canvas) which obtains to the fourth dimension – namely the passage of Time emanating from a pictorial art. If Picasso is the ‘big man on campus’ of 20th century Modernism, it’s because his analysis of subjects like figures and portraits could be ‘shattered’ cubistically and re-arranged into ‘facets’ that visually revolved around themselves, giving the viewer the experience of seeing a painting in the round – all 360º – as if a flat work of art were a sculpture, around which one walks to see its every side. Inherent in sculpture, it was miraculous at the time that Picasso could create this same in-the-round effect in painting and drawing, a revolution in visual arts and optics. -

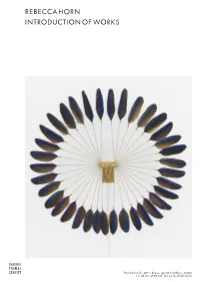

Rebecca Horn Introduction of Works

REBECCA HORN INTRODUCTION OF WORKS • Parrot Circle, 2011, brass, parrot feathers, motor t = 28 cm, Ø 67 cm | d = 11 in, Ø 26 1/3 in Since the early 1970s, Rebecca Horn (born 1944 in Michelstadt, Germany) has developed an autonomous, internationally renowned position beyond all conceptual, minimalist trends. Her work ranges from sculptural en- vironments, installations and drawings to video and performance and manifests abundance, theatricality, sensuality, poetry, feminism and body art. While she mainly explored the relationship between body and space in her early performances, that she explored the relationship between body and space, the human body was replaced by kinetic sculptures in her later work. The element of physical danger is a lasting topic that pervades the artist’s entire oeuvre. Thus, her Peacock Machine—the artist’s contribu- tion to documenta 7 in 1982—has been called a martial work of art. The monumental wheel expands slowly, but instead of feathers, its metal keels are adorned with weapon-like arrowheads. Having studied in Hamburg and London, Rebecca Horn herself taught at the University of the Arts in Berlin for almost two decades beginning in 1989. In 1972 she was the youngest artist to be invited by curator Harald Szeemann to present her work in documenta 5. Her work was later also included in documenta 6 (1977), 7 (1982) and 9 (1992) as well as in the Venice Biennale (1980; 1986; 1997), the Sydney Biennale (1982; 1988) and as part of Skulptur Projekte Münster (1997). Throughout her career she has received numerous awards, including Kunstpreis der Böttcherstraße (1979), Arnold-Bode-Preis (1986), Carnegie Prize (1988), Kaiserring der Stadt Goslar (1992), ZKM Karlsruhe Medienkunstpreis (1992), Praemium Imperiale Tokyo (2010), Pour le Mérite for Sciences and the Arts (2016) and, most recently, the Wilhelm Lehmbruck Prize (2017). -

Eduardo Chillida

Press Release Eduardo Chillida Hauser & Wirth New York, 69th Street 30 April – 27 July 2018 Private view: Monday 30 April, 6 – 8 pm The bird is one of the signs of space, each one of Chillida’s sculptures represents, much like the bird, a sign of space; each one of them says a different thing: the iron says wind, the wood says song, the alabaster says light yet they all say the same thing: space. A rumor of limits, a coarse song; the wind, an ancient name of the spirit, blows and spins tirelessly in the house of space. – Octavio Paz New York… Hauser & Wirth is pleased to present its inaugural exhibition of works by Eduardo Chillida (1924 – 2002), Spain’s foremost sculptor of the twentieth century. Widely recognized for monumental iron and steel public sculptures displayed across the globe, Chillida is also celebrated for a wholly distinctive use of materials such as stone, chamotte clay, and paper to engage concerns both earthly and metaphysical. On view from 30 April through 27 July 2018, this exhibition showcases the artist’s varied and innovative practice through a focused presentation of rarely displayed works, including small-scale sculptures, collages, drawings, and artist books that shed new light on Chillida’s enduring fascination with space and organic form. Originally a student of architecture in Madrid, Chillida created art guided by its principles; his early interest in the field had a lasting impact on his development as an artist, shaping his understanding of spatial relationships and sparking what would become a deep-rooted interest in making space visible through a consideration of the forms surrounding it. -

1947 Drops out of Architecture School to Study Drawing at the Círculo De Bellas Artes in Madrid. Works in José Martínez Repul

1947 Drops out of architecture school to study drawing at the Círculo de Bellas Artes in Madrid. Works in José Martínez Repullés's sculpture studio, where he creates his first sculpture. 1948 Moves to Paris, where he forges a friendship with artist Pablo Palazuelo. 1949 Participates in the Salon de Mai in Paris. 1950 Takes part in the exhibition Les mains éblouiesat Galerie Maeght in Paris. Marries Pilar Belzunce. 1951 Returns to the Spanish province of Guipúzcoa, settling in Hernani. Creates his first work in bronze. 1954 Has his first solo exhibition in Spain, at Galería Clan in Madrid. Creates four doors for the Basílica Nuestra Señora de Aránzazu in Oñate, Spain. 1955 The Kunsthalle Bern presents an exhibition of his work. 1956 Exhibits at Galerie Maeght in Paris. 1958 Receives the International Grand Prize for Sculpture at the XXIX Biennale di Venezia. Chillida's work is featured in Sculpture and Drawings from Seven Sculptors at the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum in New York. Receives the Graham Foundation Award and exhibits at the Graham Foundation in Chicago. 1959 Participates in Documenta 2 in Kassel, Germany. Creates his first etchings, first works in wood, and first works in steel. 1960 Receives the Kandinsky Prize, awarded by the “ArtChronika” Cultural Fund. Forges a friendship with sculptor Alberto Giacometti. 1961 Exhibits at Galerie Maeght in Paris. 1964 Receives the Carnegie Prize, awarded by the Carnegie Museum of Art in Pittsburgh. 1965 Exhibits at Tunnard Gallery in London and the Kestnergesellschaft Hannover. 1966 The Museum of Fine Arts in Houston organizes a retrospective exhibition of Chillida's work. -

Autumn 2020 FILM and TELEVISION DEALS Spellslinger Series – Sebastien De Castell Marge in Charge Series – Isla Fisher We Were Liars – E

Rights Guide Autumn 2020 FILM AND TELEVISION DEALS Spellslinger series – Sebastien de Castell Marge in Charge series – Isla Fisher We Were Liars – E. Lockhart Love Letters to the Dead – Ava Dellaira Cell 7 – Kerry Drewery CONTENTS Our Chemical Hearts – Krystal Sutherland Frogkisser! – Garth Nix YOUNG ADULT 4 S.T.A.G.S. – M. A. Bennett TEEN 14 The Cruel Prince (Folk of the Air) series – Holly Black NINE TO TWELVE 21 Charlie and Me – Mark Lowery ILLUSTRATED FICTION 30 The Boy Who Grew Dragons – Andy Shepherd PICTURE BOOKS 38 The Girl Who Drank the Moon – Kelly Barnhill ANTHOLOGY 40 Iremonger series - Heap House, Foulsham, Lungdon – Edward Carey NON-FICTION 41 Birdy – Jess Vallance BACKLIST 46 Stepsister – Jennifer Donnelly Genuine Fraud – E. Lockhart The Wild Robot – Peter Brown Enola Holmes – Nancy Springer 36 Questions That Changed My Mind About You – Vicki Grant The Ghost Bride – Yangsze Choo The Last Human – Lee Bacon The Distance Between Me and the Cherry Tree – Paola Peretti With the Fire on High – Elizabeth Acevedo The Witch’s Boy – Kelly Barnhill The Tattooist of Auschwitz – Heather Morris The Red Ribbon – Lucy Adlington The Old Kingdom series – Garth Nix Perfectly Preventable Deaths – Deirdre Sullivan A Semi-Definitive List of Worst Nightmares – Krystal Sutherland The Keys to the Kingdom series – Garth Nix Night Shift - Debi Gliori 3 YOUNG ADULT YOUNG ADULT Chris Whitaker Yasmin Rahman THE FOREVERS THIS IS MY TRUTH What would you do if you could get There are some secrets that even best away with anything? friends don’t tell each other . They called it Selena. -

The Museum of Modern Art

The Museum of Modern Art For Immediate Release November 1991 RICHARD SERRA: AFANGAR ICELANDIC SERIES November 26, 1991 - March 24, 1992 Richard Serra's most ambitious set of prints to date, made to celebrate the twenty-fifth anniversary of Gemini G.E.L., are the subject of an exhibition at The Museum of Modern Art opening on November 26, 1991. Organized by Riva Castleman, director of the Department of Prints and Illustrated Books, RICHARD SERRA: AFANGAR ICELANDIC SERIES is the first exhibition of the project, which consists of more than a dozen heavily encrusted etchings that the artist calls intaglio constructions. The works in the series employ the visual vocabulary of a recent project of Serra's in which he had wery tall monoliths of Icelandic basalt placed in pairs along the perimeter of a small island near Reykjavik. In the etchings, made at Gemini G.E.L. in Los Angeles in 1991, densely black forms have been printed on roughly textured paper affixed in the printing process to two layers of Oriental paper. These imposing images loom upward from the lower edges of the sheets, starkly evoking the environment that inspired them. The exhibition continues through March 24, 1992. Richard Serra was born in San Francisco, California, in 1939. He studied at the Berkeley and Santa Barbara campuses of the University of California, graduating with a B.S. in English Literature in 1961. In 1964 he earned an M.F.A. from Yale University, where he had worked with Josef Albers on his historic book The Interaction of Color. -

William Kentridge: ‘Seeing Double’

M A R I A N G O O D M A N G A L L E R Y For Immediate Release. William Kentridge: ‘Seeing Double’ January 16 – February 16, 2008 Opening reception: Wednesday, January 16, 2008, 6-8 pm Marian Goodman Gallery is pleased to present an exhibition of recent work by William Kentridge which will open on January 16th and will run through February 16th, 2008. The exhibition will be on view in the North and South Galleries. This will be the first presentation in the U.S. of works previously seen this summer and fall at the Städel Museum, Frankfurt and the Kunsthalle Bremen. The exhibition is structured primarily around the discourse of vision and optics and centered around a new eight-minute anamorphic film, titled What Will Come (2006), which takes its title from a Ghanaian proverb: “What will come has already come.” On view will be drawings, prints, and stereoscopic images which form the basis of the film What Will Come and in which Kentridge continues his exploration of optics and the construction of seeing. In taking sight as a subject, it is double vision, the formal construction of how we construct images in our brain which intrigues Kentridge. This is revealed through a set of eight stereoscopic cards, Double Vision, six stereoscopic photogravures, and drawings, all of which take on three dimensions as the viewer ‘completes’ the work with a stereoscopic device; as well as anamorphic drawings-- images which appear distorted, but are corrected in mirrored in cylinders. Reference to optics have been an ongoing concern in Kentridge’s work since, for example, the film Stereoscope (1999) in which “Soho’s mind bursts into two as he doubles up and becomes divided even from himself –unable to achieve the stereoscopic vision by which we normally see three-dimensionally as our mind fuses together images from both eyes”, or since Kentridge’s group of anamorphic drawings based on Shadow Procession figures in 2000. -

CHANGING the EQUATION ARTTABLE CHANGING the EQUATION WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP in the VISUAL ARTS | 1980 – 2005 Contents

CHANGING THE EQUATION ARTTABLE CHANGING THE EQUATION WOMEN’S LEADERSHIP IN THE VISUAL ARTS | 1980 – 2005 Contents 6 Acknowledgments 7 Preface Linda Nochlin This publication is a project of the New York Communications Committee. 8 Statement Lila Harnett Copyright ©2005 by ArtTable, Inc. 9 Statement All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted Diane B. Frankel by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or information retrieval system, without written permission from the publisher. 11 Setting the Stage Published by ArtTable, Inc. Judith K. Brodsky Barbara Cavaliere, Managing Editor Renée Skuba, Designer Paul J. Weinstein Quality Printing, Inc., NY, Printer 29 “Those Fantastic Visionaries” Eleanor Munro ArtTable, Inc. 37 Highlights: 1980–2005 270 Lafayette Street, Suite 608 New York, NY 10012 Tel: (212) 343-1430 [email protected] www.arttable.org 94 Selection of Books HE WOMEN OF ARTTABLE ARE CELEBRATING a joyous twenty-fifth anniversary Acknowledgments Preface together. Together, the members can look back on years of consistent progress HE INITIAL IMPETUS FOR THIS BOOK was ArtTable’s 25th Anniversary. The approaching milestone set T and achievement, gained through the cooperative efforts of all of them. The us to thinking about the organization’s history. Was there a story to tell beyond the mere fact of organization started with twelve members in 1980, after the Women’s Art Movement had Tsustaining a quarter of a century, a story beyond survival and self-congratulation? As we rifled already achieved certain successes, mainly in the realm of women artists, who were through old files and forgotten photographs, recalling the organization’s twenty-five years of professional showing more widely and effectively, and in that of feminist art historians, who had networking and the remarkable women involved in it, a larger picture emerged. -

Special Exhibitions of Work by the Following Artists : Paintings by John

N 6510 S64 1916 NMAA SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO, DECEMBER 12 1916 TO JANUARY 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE o WQ> SPECIAL EXHIBITIONS OF WORK BY THE FOLLOWING ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY JOHN W. ALEXANDER SCULPTURE BY CHESTER BEACH PAINTINGS BY CALIFORNIA ARTISTS PAINTINGS BY WILSON IRVINE PAINTINGS BY EDWARD W. REDFIELD PAINTINGS, DRAWINGS AND SKETCHES BY MAURICE STERNE THE ART INSTITUTE OF CHICAGO DEC. 12, 1916 TO JAN. 2, 1917 PAINTINGS BY JOHN WHITE ALEXANDER ; JOHN W. ALEXANDER. Born, Pittsburgh. Pennsylvania, 1856. Died, New York, May 31, 1 91 5. Studied at the Royal Academy, Munich, and with Frank Duveneck. Societaire of Societe Nationale des Beaux Arts, Paris; Member of the International Society of Sculptors, Painters and Gravers, London Societe Nouvelle, Paris ; Societaire of the Royal Society of Fine Arts, Brussels ; President of the National Academy of Design, New York; President of the National Academy Association ; President of the National Society of Mural Painters, New York; Ex- President of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, New York ; American Academy of Arts and Letters Vice-President of the National Fine Arts Federation, Washington, D. C. ; Member of the Architectural League, Fine Arts Federation and Fine Arts Society, New York ; Honorary Member of the Secession Society, Munich, and of the Secession Society, Vienna ; Hon- orary Member of the Royal Society of British Artists, of the American Institute of Architects and of the New York Society of Illustrators ; President of the School Art League, New York ; Trustee of the New York Public Library ; Ex-President of the MacDowell Club, New York ; Trustee of the Metropolitan Museum of Art ; Trustee of the American Academy in Rome ; Chevalier of the Legion of Honor, France; Honorary Degree of Master of Arts, Princeton University, 1892, and of Doctor of Literature, Princeton, 1909. -

Art in America February 2005 Pg. 84 - 91

Art in America February 2005 Pg. 84 - 91 Captivating Strangers By Gregory Volk These are good days for Kutlug Ataman, a 43-year-old Turkish artist who divides his time between Istanbul, London and elsewhere. He has a new video installation in the Carnegie International, for which he won the Carnegie Prize; he was a finalist for Great Britain’s prestigious Turner Prize; he recently presented another impressive video piece at Lehmann Maupin in New York; and he is also preparing for a retrospective at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sydney later this year. That’s not bad for someone who wasn’t even exhibiting visual art per se until 1997, although he has been making experimental and feature films for a while, oftentimes to considerable acclaim. Ataman and the conceptually minded sculptor Ayse Erkmen are now broadly recognized as the two premier contemporary Turkish artists; like Erkmen, Ataman is one of the few Turkish artists in recent memory to enjoy a robust international reputation. Most of his career, however, has transpired far from his home country, due to the fact that, aside from the acclaimed Istanbul Biennial, Turkey has not developed an arts infrastructure capable of supporting such a professional life. It was the 1997 version of the Istanbul Biennial, curated by Rosa Martinez, that first brought Ataman to the attention of a large international art audience, for his kutlug ataman’s semiha b. unplugged (1997), a quirky documentary concerning the (at the time) 87-year-old, decidedly eccentric Turkish opera singer Semiha Berksoy. This was also my first encounter with Ataman’s work.