Nine Ways of Opening <I>Macbeth</I>

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Whole Fanzine11.Pdf

EDITORIAL THE WHOLE FANZINE CATALOG 11/12 BRIAN EARL BROWN 16711 BURT R 07 it's late DETROIBMI . USA ■Well,I think this is a late issue since I intended tci .get it out about three weeks ago, which would have been 6 weeks after the last issue of hlofan should have been out. That was delayed,too.... That's one . reason why, if you'll check the indica below, you'll see that WoFan is now listed as a bimonthly publication TABLE OF CONTENTS There's a lot of bother to publishing an issue and I want to cut -bock a little on that bother. CHANGES Editorial page 2 In fact WoFan is going to be changing a lot in the Booksellers page A next few issues, a fact that you probably won't notice Clubzines page A because it's been different every time its come out. The most noticable difference is that starting with Newszines page A this issue, it's being mailed by via bulk mailing. Coraiczines page 5 There are currently about 150 US copies which isn't the magical 200 copies that the post office requires, Genzines but it's cheaper to mail out 200 by Bulk than it is to Australia page 6 mail 150 copies by fir,st class mail, and even more . with a double-sized issue like this. The 50 extra Canada page 7 copies will be mailed back to myself, then pi-obably England page 7 mailed overseas. It's kind of nasty of my to mail overseas fans 'used' fanzines, but I've been trying fr France page 7 from the first to find ways to make WoFan a breakeven Neu Zealand page 8 publication and I certainly can use the savings in postage that a bulk mailing will allow. -

Democratizing E-Book Retailing

3,000 plus Join us and more than 3,000 publishers in Democratizing E-Book Retailing 10 Finger Press Acrobat Books Alan Phillips 121 Publications Action Publishing LLC Alazar Press 1500 Books Active Interest Media, Inc. Alban Books 3 Finger Prints Active Parenting Albion Press 3G Publishing, Inc. Adair Digital Alchimia 498 Productions, LLC Adaptive Studios Alden-Swain Press 4th & Goal Publishing Addicus Books Aleph Book Company Pvt.Ltd 5Points Publishing Adlai E. Stevenson III Algonquin Books 5x5 Publications Adm Books Ali Warren 72nd St Books Adriel C. Gray Alight/Swing Street Publishing A & A Johnston Press Advanced Perceptions Inc. Alinari 24 Ore A & A Publishers Inc Advanced Publishing LLC All Clear Publishing A C Hubbard Advantage Books All In One Books - Gregory Du- A Sense Of Nature Adventure Street Press LLC pree A&C Publishing Adventures Unlimited Press Allen & Unwin A.R.E. Press Aepisaurus Publishing, LLC Allen Press Inc AA Publishing Aesop Press ALM Media, LLC Aadarsh Pvt Ltd Affirm Press Alma Books AAPC Publishing AFG Weavings LLC Alma Rose Publishing AAPPL Aflame Books Almaden Books Aark House Publishing AFN Alpha International Aaron Blake Publishers African American Images Altruist Publishing Abdelhamid African Books Collective AMACOM Abingdon Press Afterwords Press Amanda Ballway Abny Media Group AGA Institute Press AMERICA SERIES Aboriginal Studies Press Aggor Publishers LLC American Academy of Abrams AH Comics, Inc. Oral Medicine Absolute Press Ajour Publishing House American Academy of Pediatrics Abstract Sounds Books, Ltd. AJR Publishing American Automobile Association Academic Foundation AKA Publishing Pty Ltd (AAA) Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics Akmaeon Publishing, LLC American Bar Association Acapella Publishing Aladdin American Cancer Society, Inc. -

Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics

Wright State University CORE Scholar Browse all Theses and Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2013 Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics Kristen Coppess Race Wright State University Follow this and additional works at: https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Repository Citation Race, Kristen Coppess, "Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics" (2013). Browse all Theses and Dissertations. 793. https://corescholar.libraries.wright.edu/etd_all/793 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at CORE Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Browse all Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CORE Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. BATWOMAN AND CATWOMAN: TREATMENT OF WOMEN IN DC COMICS A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts By KRISTEN COPPESS RACE B.A., Wright State University, 2004 M.Ed., Xavier University, 2007 2013 Wright State University WRIGHT STATE UNIVERSITY GRADUATE SCHOOL Date: June 4, 2013 I HEREBY RECOMMEND THAT THE THESIS PREPARED UNDER MY SUPERVISION BY Kristen Coppess Race ENTITLED Batwoman and Catwoman: Treatment of Women in DC Comics . BE ACCEPTED IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF Master of Arts. _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. Thesis Director _____________________________ Carol Loranger, Ph.D. Chair, Department of English Language and Literature Committee on Final Examination _____________________________ Kelli Zaytoun, Ph.D. _____________________________ Carol Mejia-LaPerle, Ph.D. _____________________________ Crystal Lake, Ph.D. _____________________________ R. William Ayres, Ph.D. -

The Tragedy of Macbeth

Learning Modalities Visual/Spatial Learners Throughout the reading of Macbeth, have students refer to the photo- graph of the reconstructed Globe theater on p. 295. Suggest that they envision the action as it would take place in the acting areas. 1 About the Selection In The Tragedy of Macbeth, Act I, the The Tragedy of war hero Macbeth returns home and, on the way, encounters three witches who prophesy that he will one day be king of Scotland. Seized by ruth- Macbeth less ambition and spurred on by his wife, Macbeth plans to murder King Duncan, thus setting in motion a series of events that will lead to his William Shakespeare eventual downfall. 2 Background Reading Shakespeare Many students will find Shakespeare’s language a challenge. He uses words and structures not familiar to the modern ear. This situation is less of a problem in a theater, where actors communicate meaning through their interpretation, but it does pose a problem for readers. (Underscore 1 that the richness of the language and insights into human nature make Shakespeare worth the work.) 2 Background The Elizabethans viewed the universe, in its ideal It may help students to see a per- state, as both orderly and interconnected. They believed that a great chain formance. Encourage them to watch linked all beings, from God on high to the lowest beasts and plants. They one of the recent film versions of also believed that universal order was based on parallels between different Shakespeare’s plays, to hear how the realms. Just as the sun ruled in the heavens, for example, the king ruled language sounds in performance. -

Children of the Atom Is the First Guidebook Star-Faring Aliens—Visited Earth Over a Million Alike")

CONTENTS Section 1: Background............................... 1 Gladiators............................................... 45 Section 2: Mutant Teams ........................... 4 Alliance of Evil ....................................... 47 X-Men...................................... 4 Mutant Force ......................................... 49 X-Factor .................................. 13 Section 3: Miscellaneous Mutants ........................ 51 New Mutants .......................... 17 Section 4: Very Important People (VIP) ................. 62 Hellfire Club ............................. 21 Villains .................................................. 62 Hellions ................................. 27 Supporting Characters ............................ 69 Brotherhood of Evil Mutants ... 30 Aliens..................................................... 72 Freedom Force ........................ 32 Section 5: The Mutant Menace ................................79 Fallen Angels ........................... 36 Section 6: Locations and Items................................83 Morlocks.................................. 39 Section 7: Dreamchild ...........................................88 Soviet Super-Soldiers ............ 43 Maps ......................................................96 Credits: Dinosaur, Diamond Lil, Electronic Mass Tarbaby, Tarot, Taskmaster, Tattletale, Designed by Colossal Kim Eastland Converter, Empath, Equilibrius, Erg, Willie Tessa, Thunderbird, Time Bomb. Edited by Scintilatin' Steve Winter Evans, Jr., Amahl Farouk, Fenris, Firestar, -

LGBTQ+ GUIDE to COMIC-CON@HOME 2021 Compiled by Andy Mangels Edited by Ted Abenheim Collage Created by Sean (PXLFORGE) Brennan

LGBTQ+ GUIDE TO COMIC-CON@HOME 2021 Compiled by Andy Mangels Edited by Ted Abenheim Collage created by Sean (PXLFORGE) Brennan Character Key on pages 3 and 4 Images © Respective Publishers, Creators and Artists Prism logo designed by Chip Kidd PRISM COMICS is an all-volunteer, nonprofit 501c3 organization championing LGBTQ+ diversity and inclusion in comics and popular media. Founded in 2003, Prism supports queer and LGBTQ-friendly comics professionals, readers, educators and librarians through its website, social networking, booths and panel presentations at conventions. Prism Comics also presents the annual Prism Awards for excellence in queer comics in collaboration with the Queer Comics Expo and The Cartoon Art Museum. Visit us at prismcomics.org or on Facebook - facebook.com/prismcomics WELCOME We miss conventions! We miss seeing comics fans, creators, pros, panelists, exhibitors, cosplayers and the wonderful Comic-Con staff. You’re all family, and we hope everyone had a safe and productive 2020 and first half of 2021. In the past year and a half we’ve seen queer, BIPOC, AAPI and other marginalized communities come forth with strength, power and pride like we have not seen in a long time. In the face of hate and discrimination we at Prism stand even more strongly for the principles of diversity and equality on which the organization was founded. We stand with the Black, Asian American and Pacific Islander, Indigenous, Latinx, Transgender communities and People of Color - LGBTQ+ and allies - in advocating for inclusion and social justice. Comics, graphic novels and arts are very powerful mediums for marginalized voices to be heard. -

Word River Literary Review

Kevin P. Keating In the Secret Parts of Fortune -1- Let me make it clear from the very start that it was Elsie, not I, who decided that Gonzago must die. On those cold autumn nights when she let me visit her bed, Elsie chased the dog from the house, mainly because she couldn‘t stomach the animal‘s crude pantomime of our twice-monthly romps. It stared at us while we made love, panting to the irregular rhythm of the bedsprings, swabbing its own genitalia with a dripping, lolling tongue of magnificent reach and precision, growling and gnashing its teeth whenever I clutched the sides of the mattress and unleashed my ridiculous yowls of rapture into the pillow. Sensing a conspiracy, Elsie locked the door and confided that the Great Dane was only playing the part of a voyeur. Its real intention was to carefully observe everything that went on in the house while its master was away on business and then to reenact it all for him upon his return. I patiently listened to my darling‘s fanciful theory and wondered, not without a little self-pity, how the simple perversions of a dirty old dog and the delusions of a half-mad woman, whose bookshelves were crammed with paperbacks on astrology and ESP and self-hypnosis, could continually thwart my modest ambitions--love and frustration, the sad little ritual of a middle-aged man. By then, of course, I‘d come to accept the fact that when enormous sums of money were at stake paranoia became an almost palpable thing, as real as a shivering sentinel standing guard outside the door, waiting night and day for signs of a possible invasion. -

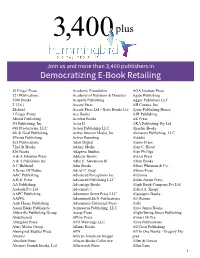

Democratizing E-Book Retailing

3,400 plus Join us and more than 3,400 publishers in Democratizing E-Book Retailing 10 Finger Press Academic Foundation AGA Institute Press 121 Publications Academy of Nutrition & Dietetics Agate Publishing 1500 Books Acapella Publishing Aggor Publishers LLC 2.13.61 Accent Press AH Comics, Inc. 2dcloud Accent Press Ltd - Xcite Books Ltd Ajour Publishing House 3 Finger Prints Ace Books AJR Publishing 3dtotal Publishing Acrobat Books AK Press 3G Publishing, Inc. Actar D AKA Publishing Pty Ltd 498 Productions, LLC Action Publishing LLC Akashic Books 4th & Goal Publishing Active Interest Media, Inc. Akmaeon Publishing, LLC 5Points Publishing Active Parenting Aladdin 5x5 Publications Adair Digital Alamo Press 72nd St Books Adams Media Alan C. Hood 826 Books Adaptive Studios Alan Phillips A & A Johnston Press Addicus Books Alazar Press A & A Publishers Inc Adlai E. Stevenson III Alban Books A C Hubbard Adm Books Albert Whitman & Co. A Sense Of Nature Adriel C. Gray Albion Press A&C Publishing Advanced Perceptions Inc. Alchimia A.R.E. Press Advanced Publishing LLC Alden-Swain Press AA Publishing Advantage Books Aleph Book Company Pvt.Ltd Aadarsh Pvt Ltd Adventure 1 Alfred A. Knopf AAPC Publishing Adventure Street Press LLC Algonquin Books AAPPL AdventureKEEN Publications Ali Warren Aark House Publishing Adventures Unlimited Press Alibi Aaron Blake Publishers Aepisaurus Publishing, LLC Alice James Books Abbeville Publishing Group Aesop Press Alight/Swing Street Publishing Abdelhamid Affirm Press Alinari 24 Ore Abingdon Press AFG Weavings LLC Alive Publications Abny Media Group Aflame Books All Clear Publishing Aboriginal Studies Press AFN All In One Books - Gregory Du- Abrams African American Images pree Absolute Press African Books Collective Allen & Unwin Abstract Sounds Books, Ltd. -

History of the Marvel Universe Kindle

HISTORY OF THE MARVEL UNIVERSE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Marvel Press Book Group | 232 pages | 13 Jul 2021 | Marvel | 9781302928292 | English | none History of the Marvel Universe PDF Book Kevin Thompson, a young boy born afflicted with a terminal brain infection, is subjected to torturous medical treatments by his scientist parents in order to save his life. In AD, the coastal village of Lakstad , Norway was wiped from the map when Harald Jaekelsson and his crew murdered the entire population of the town. Dracula later waged a bloody war against the gypsies as revenge for Lianda's actions. At one point wielded as tools and weaponry of powerful beings called Celestials, they are eventually scattered across the universe and become sought after by all manner of powerful beings for eons. One race achieved immortality and great power, but after an attempt to help two other civilizations that ended in their mutual destruction, decided not to interfere anymore, but only to record all events in the universe. Details of his life are sketchy, but his exploits will eventually become well known enough in popular culture to inspire a comic book and a feature film. This sequence of events mirrors a similar situation in one of Marvel's most infamous unfinished tales , John Byrne's The Last Galactus Story. Over time, at least two of the Infinity Stones are given new physical forms: The Space Stone becomes an energy cube known as The Tesseract, while the Reality Stone becomes a seemingly- sentient red liquid known as The Aether. Shipping to: Worldwide. D-sponsored despite Widow, Hawkeye and sometime later Captain America remaining employed at the Agency. -

X-Cutioner's Song Event

8 A MARVEL HEROIC RPG EVENT BY JAYSON JOLIN 8 X-CUTIONER’S SONG ! This full-featured Event for MARVEL HEROIC ROLEPLAYING is based on the Marvel X- Cutioner Song crossover published between November 1992 and January 1993. It ran through four titles featuring Marvel’s mighty mutants: Uncanny X-Men 294-296 written by Scott Lobdell, X-Factor 84-86 written by Peter David, X-Men 14-16 written by Fabian Nicieza, and X-Force 16-18 also written by Fabian Nicizea. ! This Event is ideally suited for the Trope style of play (see the Civil War Event Book, page CW04, for the rules for Trope play). Have the players select a datafile for each of the X-teams (X- Factor, X-Force, X-Men Blue and X-Men Gold) if they wish to play in this style. This will give them the opportunity to work each side of this conflict, keeping the tension high between the groups even when they come together to fight Stryfe at the Event’s climax. STRUCTURE OF THE EVENT ! X-CUTIONER’S SONG is an event in three Acts. The story centers on the mutant villain Stryfe and his mad plot to inflict vengeance upon Jean Grey and Scott Summers, whom he believes are his parents, and his “spiritual” father, Apocalypse. Encompassing two teams of X-Men, X-Factor and X- Force, this Event gives players tremendous opportunity to flex their mutant muscles and allows the Watcher to run an action-packed storyline that touches of subjects ranging from civil liberties to sibling rivalry. -

X-Men � � � Treatment � � by � � Michael Chabon � � � � � � �

X-MEN TREATMENT BY MICHAEL CHABON July 17, 1996 Converted to PDF for http://www.pdfscreenplays.net FADE IN: A grainy television image. Streams and eddies of blue pixels. From the blur of electronic protoplasm emerge the outlines of a large head, a snub nose. A fluttering of little fingers. The sonogram freezes. A pair of tiny horns twist like whelks from the unborn child's head. We hear the whine of a printer. A technician tears off a hard copy image of the horned baby. A man in a suit studies the printout. He smiles. Then he reaches for a phone. ON A DESERT HIGHWAY A battered pickup blows past. The driver is a young Latino man, his wife beside him, hugely pregnant, grim and silent with the pain of labor. They race by a gas station hung with X-mas lights. The young man looks in his rear-view. Flashing lights. An old-fashioned ambulance--a white hearse--is in hot pursuit, siren wailing. The young man desperately tries to coax more speed out of his rattling truck. The landscape is empty again but for the deserted gas station wasting its light on the desert evening. Twilit mountains loom behind it. Faint strains of "Silent Night" from the office radio. The dust of the two vehicles hangs, motionless. SOMEWHERE IN THE CANADIAN ROCKIES Ribbons of diamond dust twist across a white expanse. Gray winter sky, distant black treeline. A figure runs across the waste, naked, bleeding from a dozen wounds, caught in the terrible jaw of the mountains. -

Docunirr RESUME

DocunirrRESUME ED 314 757 CS 212 196 TITLE Common Ground 1989: Suggested Literature for Alaskan Schools, Grades K-8. INSTITUTION Alaska State Dept. of Education, Juneau. PUB DATE May 89 NOTE 130p.; For tha guide for grades 7-12, see ED 309 447. PUB TYPE Guides - Non-Classroom Use (055) -- Reference Materials - Bibliographies (131) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC06 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS Alaska Natives; Elementary Education; Ethnic Groups; *Literature Appreciation; *Reading Materials; *Reading Material Selection; State Curriculum Guides IDENTIFIERS *Alaska; Whole Language Approach ABSTRACT Intended to assist Alaskan school districts in their own selection and promotion of reading and literature, this guide to literature for use in grades K-8 has five purposes: (1) to encourage reading and the use of literature throughout Alaskan schools; (2) to promote the inclusion of Alaska native literature, and minority literature, in addition to the traditional Eastern and Western classics; (3) to help curriculum planners an. committees to select books and obtain ideas for thematic units using literature; (4) to stimulate local educators to evaluate the use of literature in their schools and consider ways to use it as core material and as recreational reading; and (5) to accompany the state's Model Curriculum Guide in Language Arts, K-12, supplementing the references to literature, and to promote the reading of literature as an activity expected of all Alaskan students. Contents include: Foreword; Preface; Acknowledgments; Introduction and Overview; Basic Intent