The Development of Tea in Japan from Kissa to Chanoyu - the Title Relationship Between the Warrior Class and Tea

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Look Through the Heart Teahouse”

ShinKanAn Teahouse – The “Look Through the Heart Teahouse” 1. Introduction: History and Name • Our Teahouse in unique on the Central Coast. It is a traditional structure, using mostly Japanese joinery instead of nails, traditional tatami mats and hand-made paper sliding doors. Additionally, it is perhaps the only traditional Japanese Teahouse between the Greater Los Angeles area and the San Francisco peninsula, and the only one in California using California natives in an intentional Japanese style. • It was originally built in Kyoto during the postwar period: a wooden plaque on the wall near the entry doors commemorates the architect and the date: 1949. The Teahouse was a gift from the President of the Nippon Oil Company to a local resident, Mr. H. Royce Greatwood, as an expression of appreciation for his assistance after the war. It was shipped in wooden boxes, each piece numbered, and reassembled in Mr. Greatwood’s Hope Ranch lemon orchard in the early 1950’s. This teahouse is evidence of the tremendous efforts that were made to renew the ties of friendship between former wartime adversaries. • The rich cultural tradition of Cha-do, The Way of Tea, graces this teahouse. In 2000, it was given the name ShinKanAn , meaning “Look Through the Heart” by the 15th Grandmaster of the Urasenke Tea school, an unusual event. • The name was generously given in honor of Heartie Anne Look, a teacher of flower arrangement and Japanese culture for many years in the Santa Barbara community. This teahouse is being used and maintained in a manner authentic to the tradition of Cha-do. -

Based on the Most Classic Cocktails, but with an Asian Twist, These Cocktails Have Been Created by Roji for Anyone Who Follows the Path of Roji

Based on the most classic cocktails, but with an Asian twist, these cocktails have been created by Roji for anyone who follows the path of Roji. Please feel free to order your favorite classic cocktail even if it is not mentioned on this menu. The Nomu 13 Ketel One Vodka, Cointreau, Yuzu, Litchi, Bitters, Egg White Sweet with a Japanese twist Walking To Paradise 14 Johnnie Walker Black Label, Raspberry Liqueur, Lime, Butterscotch, Egg white Keep Walking... Budo 13 Hendrick’s Gin, Cointreau,Grapes, Cucumber, Elderfower, Lime Perfect Start Of Your Wonderful Evening Rojitini 14 Mount Gay Eclipse Rum, Elderfower, Lime Sweet & Classy Mao 15 Mount Gay Eclipse Rum, Zacapa 23 Rum, Lime, Liquor 43, Almond Syrup, Bitters Tiki Style Man with the Red Face 14 Strawberry and basil infused Don Julio Bianco, dry vermouth, lime Spicy challenge My Medicine Penicillin 16 Monkey Shoulder Whiskey, Laphroaig 10, Ginger syrup, Honey syrup, lime Smokey, Spicy A Bitter Berry 14 Tanqueray N°Ten, Campari, Homemade Strawberry Shiso shrub Twist on a Negroni After Dinner Cocktails Smokey ‘Cohiba’ Crusta 15 Zacapa 23, Maraschino liquor, Cherry Brandy, Lime, Smoke It’s Allowed To Smoke Inside... Gentlemen’s Agreement Club 29 Johnnie Walker Blue Label, Px Sherry, Poire Williams Eau de Vie, Bitters The Perfect After Dinner at The Fire Place Lost in Translation 14 Bulleit Rye Whiskey, Fernet Branca, Sugar, Bitters Champagne Cocktails Bellefeur Champagne 14 Roji Champagne, Elderfower ‘Belfeur’ The New Bellini Champagne Russian S. Punch 15 Belvedere Vodka, Raspberry Liqueur, Crème de Cassis Topped With Our Own Roji Champagne... Roji’s Mocktails Bangkok Non-Stop 7 Blue Eyes Tea, Litchi Syrup, Ginger Syrup, Yuzu Juice and Coke. -

Fact Sheet a Look Inside the Portland Japanese Garden

Fact Sheet A look inside the Portland Japanese Garden Address: Hours: Key Personnel: 611 SW Kingston Ave Summer Public Hours (March 13 - Sept. 30): Stephen Bloom, Chief Executive Officer Portland, Oregon 97208 ● Monday: Noon - 7 p.m. Sadafumi Uchiyama, Garden Curator ● Tuesday - Sunday: 10 a.m. - 7 p.m. Diane Durston, Arlene Schnitzer Curator of Culture, Art & Education Website: japanesegarden.org Cynthia Johnson Haruyama, Deputy Director Phone: 503.223.1321 Winter Public Hours (Oct. 1 - March 12) Cathy Rudd, Board of Trustees President Email: [email protected] ● Monday: Noon - 4 p.m. Dorie Vollum, Board of Trustees President-Elect and Cultural ● Tuesday - Sunday: 10 a.m. - 4 p.m. Crossing Campaign Co-Chair Quick Facts: Pricing: ● Year Established: 1963 Adults: $14.95 ● Total Annual Attendance: 356,000 in 2016 (up 20% from 2015) Seniors (65+): $12.95 ● Total Acreage: 8 public gardens spread over 12 acres College Students (with ID): $11.95 ● Total Volunteer Hours: 7,226 in 2016 Youth (6 - 17): $10.45 ● Total Members: 11,000 Children 5 and under: free ● Total Staff: 83 regular employees, including eight full-time gardeners ● Total Operating Budget: $9.5 million Photos, Videos & Logos: ● Click here for Photos of the Garden in every season ● Click here for Photos of Cultural Programming & Art Exhibitions ● Click here for Videos & B-roll ● Click here for Logos Media Inquiries: Erica Heartquist | [email protected] | 503.542.9339 Page 1 of 3 About the Portland Japanese Garden For more than 50 years, the Portland Japanese Garden has been a haven of serenity and tranquility, nestled in the scenic West Hills of Portland, OR. -

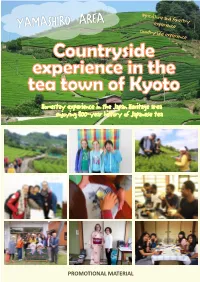

Enjoying 800-Year History of Japanese Tea

Homestay experience in the Japan Heritage area enjoying 800-year history of Japanese tea PROMOTIONAL MATERIAL ●About Yamashiro area The area of the Japanese Heritage "A walk through the 800-year history of Japanese tea" Yamashiro area is in the southern part of Kyoto Prefecture and famous for Uji Tea, the exquisite green tea grown in the beautiful mountains. Beautiful tea fields are covering the mountains, and its unique landscape with houses and tea factories have been registered as the Japanese Heritage “A Walk through the 800-year History of Japanese Tea". Wazuka Town and Minamiyamashiro Village in Yamashiro area produce 70% of Kyoto Tea, and the neighborhood Kasagi Town offers historic sightseeing places. We are offering a countryside homestay experience in these towns. わづかちょう 和束町 WAZUKA TOWN Tea fields in Wazuka Tea is an evergreen tree from the camellia family. You can enjoy various sceneries of the tea fields throughout the year. -1- かさぎちょう 笠置町 KASAGI TOWN みなみやましろむら 南山城村 MINAMI YAMASHIRO VILLAGE New tea leaves / Spring Early rice harvest / Autumn Summer Pheasant Tea flower / Autumn Memorial service for tea Persimmon and tea fields / Autumn Frosty tea field / Winter -2- ●About Yamashiro area Countryside close to Kyoto and Nara NARA PARK UJI CITY KYOTO STATION OSAKA (40min) (40min) (a little over 1 hour) (a little over 1 hour) The Yamashiro area is located one hour by car from Kyoto City and Osaka City, and it is located 30 to 40 minutes from Uji City and Nara City. Since it is surrounded by steep mountains, it still remains as country side and we have a simple country life and abundant nature even though it is close to the urban area. -

Japanese Gardens at American World’S Fairs, 1876–1940 Anthony Alofsin: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Aesthetics of Japan

A Publication of the Foundation for Landscape Studies A Journal of Place Volume ıv | Number ı | Fall 2008 Essays: The Long Life of the Japanese Garden 2 Paula Deitz: Plum Blossoms: The Third Friend of Winter Natsumi Nonaka: The Japanese Garden: The Art of Setting Stones Marc Peter Keane: Listening to Stones Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Tea and Sympathy: A Zen Approach to Landscape Gardening Kendall H. Brown: Fair Japan: Japanese Gardens at American World’s Fairs, 1876–1940 Anthony Alofsin: Frank Lloyd Wright and the Aesthetics of Japan Book Reviews 18 Joseph Disponzio: The Sun King’s Garden: Louis XIV, André Le Nôtre and the Creation of the Garden of Versailles By Ian Thompson Elizabeth Barlow Rogers: Gardens: An Essay on the Human Condition By Robert Pogue Harrison Calendar 22 Tour 23 Contributors 23 Letter from the Editor times. Still observed is a Marc Peter Keane explains Japanese garden also became of interior and exterior. The deep-seated cultural tradi- how the Sakuteiki’s prescrip- an instrument of propagan- preeminent Wright scholar tion of plum-blossom view- tions regarding the setting of da in the hands of the coun- Anthony Alofsin maintains ing, which takes place at stones, together with the try’s imperial rulers at a in his essay that Wright was his issue of During the Heian period winter’s end. Paula Deitz Zen approach to garden succession of nineteenth- inspired as much by gardens Site/Lines focuses (794–1185), still inspired by writes about this third friend design absorbed during his and twentieth-century as by architecture during his on the aesthetics Chinese models, gardens of winter in her narrative of long residency in Japan, world’s fairs. -

Teahouse N I T O

n i northwest:scale 1/8" t o b teahouse ea.r.thomson 2002 southeast:scale 1/8" N The Japanese Teahouse : Ritual and Form Buddhism had branched after about 600bc, into several distinct teachings. Of these, A Paper for M.Cohen’s Seminar on Architectural Proportion Mahayana (meaning 'big raft') Buddhism worked its way to Tibet, Mongolia, China, Korea May 2002, UBC | SoA and Japan. Of these five regional variations is the 'intuitive' school of Mayahana - or Zen. Submitted by a.r.thomson Zen (strictly literally!) means, 'meditation that leads to insight'. In order to make some sense of the Teahouse design, and more specifically its mode of Mahakasyapa, apparently, was the only acolyte present at The Flower Sermon, who proportioning, scale and materiality, it is necessary to understand something of the context understood. The Flower Sermon, it is said, was one where, "Standing on a mountain with his out of which the ‘Culture of Tea’, aka. ’Teaism’ first developed. This paper will attempt to disciples around him, Buddha did not on this occasion resort to words. He simply held aloft distill some sense of this ambient culture, and then relate the aesthetic of Zen, to the a golden lotus." (H.Smith, pg 134) components of the Teahouse proper, and finally, conclude with an examination of the proportions used in the Teahouse design. UBC’s Nitobe Teahouse was the primary resource Mahakasyapa was declared the Buddha's successor. 28 patriarchs later, in 520ad, studied, which is unique in that it is a ‘traditional’ structure on foreign soil, and thus Bodhidharma introduced the teaching of Zen to Japan. -

Japanese Tea Ceremony: How It Became a Unique Symbol of the Japanese Culture and Shaped the Japanese Aesthetic Views

International J. Soc. Sci. & Education 2021 Vol.11 Issue 1, ISSN: 2223-4934 E and 2227-393X Print Japanese Tea Ceremony: How it became a unique symbol of the Japanese culture and shaped the Japanese aesthetic views Yixiao Zhang Hangzhou No.2 High School of Zhejiang Province, CHINA. [email protected] ABSTRACT In the process of globalization and cultural exchange, Japan has realized a host of astonishing achievements. With its unique cultural identity and aesthetic views, Japan has formed a glamorous yet mysterious image on the world stage. To have a comprehensive understanding of Japanese culture, the study of Japanese tea ceremony could be of great significance. Based on the historical background of Azuchi-Momoyama period, the paper analyzes the approaches Sen no Rikyu used to have the impact. As a result, the impact was not only on the Japanese tea ceremony itself, but also on Japanese culture and society during that period and after.Research shows that Tea-drinking was brought to Japan early in the Nara era, but it was not integrated into Japanese culture until its revival and promotion in the late medieval periods under the impetus of the new social and religious realities of that age. During the Azuchi-momoyama era, the most significant reform took place; 'Wabicha' was perfected by Takeno Jouo and his disciple Sen no Rikyu. From environmental settings to tea sets used in the ritual to the spirit conveyed, Rikyu reregulated almost all aspects of the tea ceremony. He removed the entertaining content of the tea ceremony, and changed a rooted aesthetic view of Japanese people. -

Japanese Garden

満開 IN BLOOM A PUBLICATION FROM WATERFRONT BOTANICAL GARDENS SPRING 2021 A LETTER FROM OUR 理事長からの PRESIDENT メッセージ An opportunity was afforded to WBG and this region Japanese Gardens were often built with tall walls or when the stars aligned exactly two years ago! We found hedges so that when you entered the garden you were out we were receiving a donation of 24 bonsai trees, the whisked away into a place of peace and tranquility, away Graeser family stepped up with a $500,000 match grant from the worries of the world. A peaceful, meditative to get the Japanese Garden going, and internationally garden space can teach us much about ourselves and renowned traditional Japanese landscape designer, our world. Shiro Nakane, visited Louisville and agreed to design a two-acre, authentic Japanese Garden for us. With the building of this authentic Japanese Garden we will learn many 花鳥風月 From the beginning, this project has been about people, new things, both during the process “Kachou Fuugetsu” serendipity, our community, and unexpected alignments. and after it is completed. We will –Japanese Proverb Mr. Nakane first visited in September 2019, three weeks enjoy peaceful, quiet times in the before the opening of the Waterfront Botanical Gardens. garden, social times, moments of Literally translates to Flower, Bird, Wind, Moon. He could sense the excitement for what was happening learning and inspiration, and moments Meaning experience on this 23-acre site in Louisville, KY. He made his of deep emotion as we witness the the beauties of nature, commitment on the spot. impact of this beautiful place on our and in doing so, learn children and grandchildren who visit about yourself. -

The Abode of Fancy, of Vacancy, and of the Unsymmetrical

The University of Iceland School of Humanities Japanese Language and Culture The Abode of Fancy, of Vacancy, and of the Unsymmetrical How Shinto, Daoism, Confucianism, and Zen Buddhism Interplay in the Ritual Space of Japanese Tea Ceremony BA Essay in Japanese Language and Culture Francesca Di Berardino Id no.: 220584-3059 Supervisor: Gunnella Þorgeirsdóttir September 2018 Abstract Japanese tea ceremony extends beyond the mere act of tea drinking: it is also known as chadō, or “the Way of Tea”, as it is one of the artistic disciplines conceived as paths of religious awakening through lifelong effort. One of the elements that shaped its multifaceted identity through history is the evolution of the physical space where the ritual takes place. This essay approaches Japanese tea ceremony from a point of view that is architectural and anthropological rather than merely aesthetic, in order to trace the influence of Shinto, Confucianism, Daoism, and Zen Buddhism on both the architectural elements of the tea room and the different aspects of the ritual. The structure of the essay follows the structure of the space where the ritual itself is performed: the first chapter describes the tea garden where guests stop before entering the ritual space of the tea room; it also provides an overview of the history of tea in Japan. The second chapter figuratively enters the ritual space of the tea room, discussing how Shinto, Confucianism, Daoism, and Zen Buddhism merged into the architecture of the ritual space. Finally, the third chapter looks at the preparation room, presenting the interplay of the four cognitive systems within the ritual of making and serving tea. -

Vast Waters by Frederick R

Vast Waters By Frederick R. Dannaway n the year 1833, on the 15th day of the eight month, a group of Japanese tea mystics placed a jar of Chinese I depending on its source. Many tea-masters confirm the water deep into the source of the Yodo River that flows potency of specific mountain springs and show a prefer- into Kyoto, Japan. In contrast to the wasting of tea as ence for old or wild tree teas (also from famous moun- protest in Boston, these sencha adepts felt guilty in hord- tains) for both flavor and for their energy and healing ing the precious—and laboriously imported—Chinese powers. These attributes, if deduced empirically through water and so decided to release it into their home waters generations of observations as well as from a Daoist and thus share its potency with their countrymen. The “mystical primitivism”, can be seen to have retained an ring-leader of this plot, the literati tea-master Kakuo, influence from the earliest religious observances of water had requisitioned the water from China via Nagasaki in China and into Japan. On a practical level, water and and after a year’s wait was blessed with three bottles(18 tea from remote areas would indeed have special charac- liters) of the water. There was a brief reactionary re- teristics, such as taste or purity, as well as a metaphysical sponse to the plan by the government who “feared the association with the powerful mountains and wilderness Chinese water would poison the drinking supply” but that were the mystical abodes of the Immortals. -

Umami Café by AJINOMOTO CO

Umami Café BY AJINOMOTO CO. The Tea Experience For centuries, green tea has been treasured throughout Asia for its healthful, restorative qualities. In Japan, Zen priests drank green tea to keep them awake through long hours of meditation. In the 16th century, a man named Sen no Rikyù, influenced by the study of Zen, envisioned a path to enlightenment through the simple act of sharing a bowl of tea among friends in the spirit of peace and harmony—a practice he called wabi-cha. For Rikyu, making tea while mindfully engaging all the senses was to have a complete Zen experience. We are pleased to have you share a moment of quiet joy with us and experience the spirit of Japanese culture through a simple bowl of tea. Tea Sets We’ve paired traditional teas with Japanese sweets. A great place to start. Matcha with Hanabira Mochi GF V $14 Sencha with Fried Rice A bowl of hand-whisked, jade green matcha is paired with a traditional Japanese tea ceremony sweet. Tender sheets of mochi rice dough The light, sweetness of our Sencha balances nicely with the strong umami flavors of either our Yakitori Chicken Style Fried Rice ($14) or our are folded over candied burdock root and filled with sweetened white bean paste infused with a hint of miso. Takikomi Gohan Style Vegetable Fried Rice V ($12). Additional tea steepings available upon request. Sencha with Castella Cake $12 Matcha with Mochi Ice Cream GF $12 Genmaicha with Manju $11 Hojicha with Shortbread Cookies $9 The light, mild sweetness of the Sencha is enhanced by this A bowl of our hand-whisked matcha is paired with a premium Genmaicha, with its roasted rice and earthy flavor, is a perfect These bitter chocolate and vanilla cookies highlight the aromatic popular Japanese sponge cake. -

Design Examples Informational Handouts Check Online for Available Templates –

BRAND BOOK Design Examples Informational Handouts Check online for available templates – www.csus.edu/brand 2.18 HEADLINE OR EVENT HEADLINE OR NAME OF NAME GOES HERE YOUR EVENT GOES HERE This is where your event subhead goes. This is where your event subhead goes. SIDE MARGIN SUBHEAD SUBHEAD Side margin is body text. Use this text Second Subhead style for your side margin. Side margin Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Body text SIDE MARGIN SUBHEAD SUBHEAD is body text. Use this text style for your goes here. Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Side margin is body text. Use the Second Subhead side margin. Side margin is body text. body text style for your side margin. Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Body text This is the body text style. Use this style for body text. This is the body text style. Use this text style for your side margin. goes here. Body text goes here. Body text goes here. Side margin is body text. Use this text Use this style for body text. This is the body text style. Use this style for body text. Side margin is body text. Use this text style for your side margin. Side This is the body text style. This is the body text style. Use this style for body text. Here is a bullet style. Use this style for your bullet points. Here is the style for your side margin. • margin is body text.