The Glocalization and Acculturation of Hiv/Aids: the Role Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Museveni and No-Party Democracy in Uganda

1 Working Paper no.73 ‘POPULISM’ VISITS AFRICA: THE CASE OF YOWERI MUSEVENI AND NO-PARTY DEMOCRACY IN UGANDA Giovanni Carbone Università degli Studi di Milano December 2005 Copyright © Giovanni Carbone, 2005 Although every effort is made to ensure the accuracy and reliability of material published in this Working Paper, the Crisis States Research Centre and LSE accept no responsibility for the veracity of claims or accuracy of information provided by contributors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior permission in writing of the publisher nor be issued to the public or circulated in any form other than that in which it is published. Requests for permission to reproduce this Working Paper, of any part thereof, should be sent to: The Editor, Crisis States Research Centre, DESTIN, LSE, Houghton Street, London WC2A 2AE. Crisis States Research Centre ‘Populism’ Visits Africa: The Case of Yoweri Museveni and No-Party Democracy in Uganda Giovanni Carbone Università degli Studi di Milano1 The widespread adoption of electoral politics in virtually all world regions during the last part of the twentieth century has been accompanied by the emergence, in a number of reformed countries, of a new form of leadership. As the political space was formally opened up and state leadership crucially came to depend on electoral appeals for social support, many would- be leaders decided to set themselves apart by contesting for power on the basis of a strong anti-political and anti-party discourse. -

Professor Mondo Kagonyera H.E. YOWERI K.MUSEVENI THE

Speech by Professor Mondo Kagonyera Chancellor, Makerere University, Kampala AT THE SPECIAL CONGREGATION FOR THE CONFERMENT OF HONORARY DOCTOR OF LAWS (HONORIS CAUSA) UPON H.E. YOWERI K.MUSEVENI THE PRESIDENT OFUGANDA AND H.E. RASHID MFAUME KAWAWA (POSTHUMOUS), FORMER 1ST VICE PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED REPUBLIC OF TANZANIA DATE: 12TH DECEMBER 2010 AT VENUE: FREEDOM SQUARE, MAKERERE UNIVERSITY, KAMPALA Your Excellency Yoweri Kaguta Museveni, President of the Republic of Uganda The First Lady, Hon Janet K. Museveni, MP The Family of His Excellency Late Rashid Mfaume Kawawa Your Excellency, Professor Gilbert Bukenya, Vice President of Uganda, Right Honorable Professor Apolo Nsibambi, Prime Minister of Uganda, Your Excellencies Ambassadors and High Commissioners Honorable Ministers and Members of Parliament Professor Venansius Baryamureeba, Vice Chancellor, Our Special Guests from Egerton University, Kenya, & the Pan African Agribusiness & Ago Industry Consortium, (PanAAC), Kenya, Members of the University Council Members of Senate Distinguished Guests Members of Staff Ladies and Gentlemen It gives me great pleasure to welcome you all, once again, to this special congregation of Makerere University in the Freedom Square. Your Excellency, allow me once again to thank you very much for having me the great honor of heading the great Makerere University. This is a historic occasion for me as the first Chancellor of Makerere University to confer the Honorary Doctorate Degree upon His Excellency President Yoweri K. Museveni, who is also the Visitor of Makerere University. I must also express my appreciation of the fact that busy as you are now, you have found time to personally honor this occasion. INTRODUCTION As Chancellor, I shall constitute a special congregation of Makerere University to confer the Doctor of Laws (Honoris Causa) upon H.E. -

List of Abbreviations

HRNJ - Uganda Human Rights Network for Journalists-Uganda (HRNJ-Uganda) Press Freedom Index Report April 2011 2 HRNJ - Uganda Contents Preface ....................................................................................................................... 5 Part I: Background .............................................................................................. 7 Introduction .......................................................................................................... 7 Elections and Media .............................................................................................. 7 Research Objective ............................................................................................... 8 Methodology ......................................................................................................... 8 Quality check ......................................................................................................... 8 Limitations ............................................................................................................. 9 Part II: Media freedom during national elections in Uganda ................................ 11 Media as a campaign tool ................................................................................... 11 Role of regulatory bodies ................................................................................... 12 Media self censorship ......................................................................................... 14 Censorship of social media -

Poor Performance Recorded in O'level

The New Vision, Monday, February 8, 2010 NATIONAL NEWS 3 Poor performance recorded in Olevel By Conan Businge 211,000 candidates who sat has improved as a result of 50% of the candidates did schools, students still find for physics passed with dis- the Government’s science not pass the minimum it hard to express them- A NUMBER of subjects in tinction, while only 1% of policy. Only 30% of exami- Grade 8. selves in writing. the 2009 O’level examina- those who sat biology nation centres had no labo- Another subject where “Examiners reported poor tions registered poor per- excelled. As for chemistry, ratories, down from 60% in students performed poorly grammar, writing of formance, with only a only 0.7 % of the over 2005. was geography. Only 1.7% incomplete sentences that handful of students getting 213,000 students had dis- The national examiners of the over 212,000 students do not convey meaning distinctions. A distinction tinction. also noted that some stu- who sat this subject got dis- and use of (unusual) is 75% and above. “Some centres lack labo- dents have difficulties with tinction. abbreviations,” Bukenya Judith Nabakooba Most candidates showed ratory apparatus during spelling technical words, “Students were finding it said. lack of practical skills and practical examinations working out graphs, hard to even locate places He also noted that most experience, according to which affected the candi- writing correct chemical on the maps,” Bukenya students have difficulty the secretary of the Uganda dates’ performance,” equations and making explained. The national using knowledge from one Body National Examinations explained Bukenya. -

Uganda Country Report

Informal Governance and Corruption – Transcending the Principal Agent and Collective Action Paradigms Uganda Country Report Frederick Golooba-Mutebi| July 2018 Basel Institute on Governance Steinenring 60 | 4051 Basel, Switzerland | +41 61 205 55 11 [email protected] | www.baselgovernance.org BASEL INSTITUTE ON GOVERNANCE This research has been funded by the UK government's Department for International Development (DFID) and the British Academy through the British Academy/DFID Anti-Corruption Evidence Programme. However, the views expressed do not necessarily reflect those of the British Academy or DFID. 1 BASEL INSTITUTE ON GOVERNANCE Table of contents 1 Introduction 4 1.1 Informal practices as drivers of corruption 4 1.2 Rationale and conceptual approach 4 1.3 Studying informal practices as drivers of corruption in Uganda 5 2 Background on informal networks in Uganda 6 2.1 Introduction 6 2.2 The electoral dimension 7 2.3 Pre-multi party election period 8 2.4 The Multi-party period 10 2.5 Links between the competition for power, use of informal practices and corruption 11 3 Use of the three Cs as mechanisms to manage the networks 13 3.1 Co-optation and Control 13 3.1.1 Top-down co-optation: appointments (disbursement of resources and favours) for supporters and opposition figures 13 3.2 Horizontal co-optation of business interests 16 3.2.1 Co-opting members of the business community 16 3.2.2 Rewarding supporters 18 3.2.3 NRM as a vehicle for the exercise of informal governance 18 3.3 Camouflage 19 3.4 The bottom-up view 20 4 Concluding -

Government Says There Have Been Sustained and Organised Efforts to Kill Some of the Rwandan Refugees Living in South Africa.&Qu

[Government says there have been sustained and organised efforts to kill some of the Rwandan refugees living in South Africa."It is clear that these incidents directly link to tensions emanating from Rwanda and are acted upon within our borders," said spokesperson for the Department of International Relations and Cooperation Clayson Monyela on Saturday.In June 2010, there was an attack on the life of General Kayumba Nyamwasa, an asylum seeker and former Rwanda Army General.] BURUNDI : Le Burundi suspend les activités d'un parti d'opposition par RFI /17-03-2014 Au Burundi, les condamnations et autres appels à la modération lancés par la communauté internationale n’y ont rien fait. Après les violents affrontements entre les militants d’un parti d’opposition et la police, qui a tiré contre les manifestants, l’heure semble être à la répression. Le gouvernement burundais vient de franchir, durant le week-end du 15 mars, un palier supplémentaire dans la voie de la répression. Le ministre burundais de l’Intérieur Edouard Nduwimana a en effet suspendu le Mouvement pour la solidarité et la sémocratie (MSD) d’activités pour quatre mois et ferme ses locaux sur toute l’étendue du pays. Ce parti d’opposition, encore sonné par les coups de boutoir qu’il vient de recevoir, a décidé de plier pour ne pas donner « un prétexte à des mesures encore plus contraignantes ». Et sur un ton sarcastique, François Nyamoya, porte-parole du MSD ajoute que « de toute façon, on était déjà suspendu de facto, car le pouvoir nous interdit systématiquement de manifester et même de tenir de simples réunions depuis des mois ». -

Media and Corruption Page 1 MEDIA and CORRUPTION

Media and Corruption Page 1 MEDIA AND CORRUPTION Editors John Baptist Wasswa Email: [email protected] [email protected] Micheal Kakooza Email: [email protected] Publisher Uganda Media Development Foundation P.O.Box 21778, Kampala Plot 976, Mugerwa Road Bukoto Tel:+256 414 532083 Email: [email protected] Website: www.umdf.co.ug UMDF President John Baptist Wasswa Email: [email protected] Project Manager Gertrude Benderana Tel: +256 772 323325 Email:[email protected] Photo Credit All Pictures courtesy of the New Vision Group and Konrad Adenauer Stiftung. Copyright We consider the stories and photographs submitted to Review to be the property of their creators, we supply their contacts so that you can source the owner or a story or photograph you might like to reprint. Our requirement is that the reprint of a story should carry a credit saying that it first appeared in the Uganda Media Review. Funding Special thanks to Konrad Adenauer Stiftung for their immense financial assistance. Page 2 Uganda Media Review Contributors Media and Corruption Page 3 Table of Contents 5. Editorial 6. Corruption and the media 9. The scourge of the brown envelope 18. Young audiences drive change in media 13. content Using new media to fight corruption 23. Digital migration in Uganda 27. Media in era of advertiser recession 33. Community radio in the age of a commercialized media system 40. Framing the Libyan war in Uganda’s vernacular tabloids 46. (Project Briefs) 46. Journalists as bearers and promoters of human rights in Uganda 48.47. Kampala Bracing journalists declaration to fight corruption 50. -

COURSE OUTLINE PAPER 245/4 SECTION A: SEX, MARRIAGE and FAMILY (A) SEX A. Contents / Values of Sex Today B. African Traditional

` COURSE OUTLINE PAPER 245/4 SECTION A: SEX, MARRIAGE AND FAMILY (A) SEX a. Contents / values of sex today b. African traditional understanding of sex c. Sources of sex education In African traditional society [ways how sex education was transmitted in African traditional society] d. Importance of sex education in African tradition e. Sources of sex education in African tradition f. How the youth come to know about sex today g. Challenges parents and other elders in society face in trying to impart sex education to the youth h. Factors leading to permissiveness in society i. Characteristics / manifestations / indicators / signs of a permissive society j. How a Christian can help reduce the dangers of permissiveness k. Major cases of sex misuse in society l. Main causes of sex misuse m. Major impact of sex misuse n. Solutions to sex misuse o. Why there were limited cases of sex deviations In African traditional society (ATS) p. The general biblical teaching about sex CASE STUDIES OF SEX DEVIATIONS 1. Pre- marital sex (Fornication) (a) Causes and effects of fornication (b) How the girl- boy relationship should be stabilized (c) Solutions to fornication 2. Prostitution (a) Causes and dangers of prostitution (b) Cases of prostitution in the bible (c) Christian solutions to prostitution (d) Why prostitution should be legalized ` (e) Extent to which prostitution is a necessary evil 3. Rape and Defilement (a) Causes and impact (b) How to reduce rape and defilement (c) The role of the courts of law in promoting rape and defilement 4. Adultery (a) Causes and effects (b) Solutions to Adultery (c) Biblical teaching on Adultery 5. -

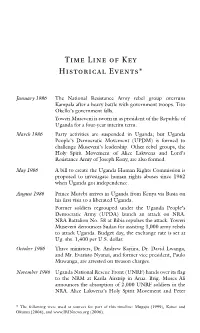

Time Line of Key Historical Events*

Time Line of Key Historical Events* January 1986 The National Resistance Army rebel group overruns Kampala after a heavy battle with government troops. Tito Okello’s government falls. Yoweri Museveni is sworn in as president of the Republic of Uganda for a four-year interim term. March 1986 Party activities are suspended in Uganda; but Uganda People’s Democratic Movement (UPDM) is formed to challenge Museveni’s leadership. Other rebel groups, the Holy Spirit Movement of Alice Lakwena and Lord’s Resistance Army of Joseph Kony, are also formed. May 1986 A bill to create the Uganda Human Rights Commission is proposed to investigate human rights abuses since 1962 when Uganda got independence. August 1986 Prince Mutebi arrives in Uganda from Kenya via Busia on his first visit to a liberated Uganda. Former soldiers regrouped under the Uganda People’s Democratic Army (UPDA) launch an attack on NRA. NRA Battalion No. 58 at Bibia repulses the attack. Yoweri Museveni denounces Sudan for assisting 3,000 army rebels to attack Uganda. Budget day, the exchange rate is set at Ug. shs. 1,400 per U.S. dollar. October 1986 Three ministers, Dr. Andrew Kayiira, Dr. David Lwanga, and Mr. Evaristo Nyanzi, and former vice president, Paulo Muwanga, are arrested on treason charges. November 1986 Uganda National Rescue Front (UNRF) hands over its flag to the NRM at Karila Airstrip in Arua. Brig. Moses Ali announces the absorption of 2,000 UNRF soldiers in the NRA. Alice Lakwena’s Holy Spirit Movement and Peter * The following were used as sources for part of this timeline: Mugaju (1999), Kaiser and Okumu (2004), and www.IRINnews.org (2006). -

HOSTILE to DEMOCRACY the Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda

HOSTILE TO DEMOCRACY The Movement System and Political Repression in Uganda Human Rights Watch New York $$$ Washington $$$ London $$$ Brussels Copyright 8 August 1999 by Human Rights Watch. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. ISBN 1-56432-239-4 Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 99-65985 Cover design by Rafael Jiménez Addresses for Human Rights Watch 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th Floor, New York, NY 10118-3299 Tel: (212) 290-4700, Fax: (212) 736-1300, E-mail: [email protected] 1522 K Street, N.W., #910, Washington, DC 20005-1202 Tel: (202) 371-6592, Fax: (202) 371-0124, E-mail: [email protected] 33 Islington High Street, N1 9LH London, UK Tel: (171) 713-1995, Fax: (171) 713-1800, E-mail: [email protected] 15 Rue Van Campenhout, 1000 Brussels, Belgium Tel: (2) 732-2009, Fax: (2) 732-0471, E-mail:[email protected] Web Site Address: http://www.hrw.org Listserv address: To subscribe to the list, send an e-mail message to [email protected] with Asubscribe hrw-news@ in the body of the message (leave the subject line blank). Human Rights Watch is dedicated to protecting the human rights of people around the world. We stand with victims and activists to prevent discrimination, to uphold political freedom, to protect people from inhumane conduct in wartime, and to bring offenders to justice. We investigate and expose human rights violations and hold abusers accountable. We challenge governments and those who hold power to end abusive practices and respect international human rights law. We enlist the public and the international community to support the cause of human rights for all. -

The Experience and Recollections from the Faculties, Schools, Institutes and Centres

8 The Experience and Recollections from the Faculties, Schools, Institutes and Centres Makerere’s Institute of Economics: New Programmes and a Contested Divorce The Harare-based African Capacity Building Foundation (ACBF), had been sponsoring a Masters degree in Economics, which taught African Economics at postgraduate level to assist African governments improve economic policy management for a number of years. McGill University in Montreal, Canada was running the programme for the English speaking African countries on behalf of the ACBF. However, after training a number of African economists at the university for some time, the ACBF was convinced that it made sense to transfer the training to Africa. McGill was not only expensive, it had another disadvantage: students studied in an alien environment, divorced from the realities of African economic problems. This necessitated a search for suitable universities in Anglophone Africa which had the capacity to host the programme. Acting on behalf of the ACBF, McGill University undertook a survey of universities in Anglophone Africa and identified two promising ones which met most of the conditions on ACBF’s checklist for hosting and servicing a regional programme of that kind. Earlier in 1996, Dr Apollinaire Ndorukwigira of the ACBF had visited Makerere to explore the possibility of Makerere participating in the new Economic Policy Management programme. On this particular visit, he said he was not making any commitments because McGill University was yet to undertake a detailed survey of a number of universities in Africa and, based on the findings, McGill University would advise the ACBF on the two most suitable universities which would host the programme. -

ESID Working Paper No. 85 the Politics of Core Public Sector Reform

ESID Working Paper No. 85 The politics of core public sector reform in Uganda: Behind the façade Badru Bukenya1 and William Muhumuza 2 April 2017 1 Department of Social Work and Social Administration Makerere University Email correspondence: [email protected] 2 Department of Political Science, Makerere University Email correspondence : [email protected] ISBN: 978-1-908749-82-6 email: [email protected] Effective States and Inclusive Development Research Centre (ESID) Global Development Institute, School of Environment, Education and Development, The University of Manchester, Oxford Road, Manchester M13 9PL, UK www.effective-states.org The politics of core public sector reform in Uganda: Behind the façade Abstract The Ugandan state presents an interesting puzzle for the advocates of public sector reforms (PSR). Whereas it has been subjected to several waves of reforms over the last three decades, these changed form but have generally not translated into significant changes in the functionality of central government. This research argues that answers to this conundrum are rooted in the country’s political settlement. Drawing on ESID’s expanded political settlement framework, the study finds that the last 15 years have seen Uganda’s ruling elite exposed to unprecedented internal and external competition leading to a shift in the balance of power from dominant to vulnerable dominant political settlement. Although the president still wields significant power, this has been used to influence government agencies to meet the short-term needs for regime maintenance, as opposed to supporting the goals of PSR implementation. Almost all PSRs are donor driven and the government accepts them not so much as a development necessity, but mainly because they are accompanied by unearned resources that are easily diverted into oiling patronage networks that maintain the elite in government.