The Use of Sports As a Tool for Diplomacy: the Case of Ghana Since Independence

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inter-Media Agenda-Setting Effects in Ghana: Newspaper Vs. Online and State Vs

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Retrospective Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2008 Inter-media agenda-setting effects in Ghana: newspaper vs. online and state vs. private Etse Godwin Sikanku Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd Part of the Journalism Studies Commons Recommended Citation Sikanku, Etse Godwin, "Inter-media agenda-setting effects in Ghana: newspaper vs. online and state vs. private" (2008). Retrospective Theses and Dissertations. 15414. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/rtd/15414 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Retrospective Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Inter-media agenda-setting effects in Ghana: newspaper vs. online and state vs. private by Etse Godwin Sikanku A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE Major: Journalism and Mass Communication Program of Study Committee: Eric Abbott (Major Professor) Daniela Dimitrova Francis Owusu Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2008 Copyright© Etse Godwin Sikanku, 2008. All rights reserved. 1457541 1457541 2008 ii TABLE OF CONTENTS LIST OF TABLES iii LIST OF FIGURES iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS v ABSTRACT vii CHAPTER 1. INTRODUCTION AND STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM 1 CHAPTER 2. LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 4 The agenda-setting theory 4 Agenda-setting research in Ghana 4 Inter-media agenda-setting 5 Online News 8 State Ownership 10 Press history in Ghana 13 Research Questions 19 CHAPTER 3. -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04Rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF OCTOBER 2005 Created on November 04rd, 2005 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O. BOX 377 JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (ARGENTINA) MARACAY 2101 -A ALAN KIM (KOREA) EDO. ARAGUA - VENEZUELA SHIGERU KOJIMA (JAPAN) PHONE: + (58-244) 663-1584 VICE CHAIRMAN GONZALO LOPEZ SILVERO (USA) + (58-244) 663-3347 GEORGE MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] MEDIA ADVISORS FAX: + (58-244) 663-3177 E-mail: [email protected] SEBASTIAN CONTURSI (ARGENTINA) Web site: www.wbaonline.com UNIFIED CHAMPION: JEAN MARC MORMECK FRA World Champion: JOHN RUIZ USA Won Title: 04-02-05 World Champion: FABRICE TIOZZO FRA Won Title: 12-13 -03 Last Defense: Won Title: 03-20- 04 Last Mandatory: 04-30 -05 _________________________________ Last Mandatory: 02-26- 05 Last Defense: 04-30 -05 World C hampion: VACANT Last Defense: 02-26- 05 WBC: VITALI KLITSCHKO - IBF: CHRIS BYRD WBC: JEAN MARC MORMECK- IBF: O’NEIL BELL WBC: THOMAS ADAMEK - IBF: CLINTON WOODS WBO : LAMON BREWSTER WBO : JOHNNY NELSON WBO : ZSOLT ERDEI 1. NICOLAY VALUEV (OC) RUS 1. VALERY BRUDOV RUS 1. JORGE CASTRO (LAC) ARG 2. NOT RATED 2. VIRGIL HILL USA 2. SILVIO BRANCO (OC) ITA 3. WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO UKR 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 3. GUILLERMO JONES (0C) PAN 3. MANNY SIACA (LAC-INTERIM) P.R. ( Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 4. RAY AUSTIN (LAC) USA 4. STEVE CUNNINGHAM USA (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) 4. GLEN JOHNSON USA ( 5. CALVIN BROCK USA 5. LUIS PINEDA (LAC) PAN 5. PIETRO AURINO ITA l 6. -

1 Tennessee Track & Field Record Book » Utsports

TENNESSEE TRACK & FIELD RECORD BOOK » UTSPORTS.COM » @VOL_TRACK 1 TRACK & FIELD RECORD BOOK TABLE OF CONTENTS GENERAL INFORMATION ALL-TIME ROSTER/LETTERMEN Table of Contents/Credits 1 All-Time Women’s Roster 52-54 Quick Facts 2 All-Time Men’s Lettermen 55-58 Media Information 2 2017 Roster 3 YEAR-BY-YEAR 1933-1962 59 COACHING HISTORY 1963-1966 60 All-Time Women’s Head Coaches 4 1967-1969 61 All-Time Men’s Head Coaches 5-6 1970-1972 62 1973-1975 63 NATIONAL CHAMPIONSHIPS 1976-1978 64 Women’s Team National Championships 7-8 1979-1981 65 Men’s Team National Championships 9-10 1981-1982 66 All-Time National Champions Leaderboard 11 1983-1984 67 Women’s Individual National Champions 12 1984-1985 68 Men’s Individual National Champions 13 1986-1987 69 1987-1988 70 THE SEC 1989-1990 71 Tennessee’s SEC Title Leaders 14 1990-1991 72 UT’s SEC Team Championships 14 1992-1993 73 All-Time Women’s SEC Indoor Champions 15 1993-1994 74 All-Time Women’s SEC Outdoor Champions 16 1995-1996 75 All-Time Men’s SEC Indoor Champions 17 1996-1997 76 All-Time Men’s SEC Outdoor Champions 18-19 1998-1999 77 1999-2000 78 ALL-AMERICANS 2001-2002 79 All-American Leaderboard 20 2002-2003 80 Women’s All-Americans 21-24 2004-2005 81 Men’s All-Americans 25-29 2005-2006 82 2007-2008 83 TENNESSEE OLYMPIANS 2008-2009 84 Olympians By Year 30-31 2010-2011 85 Medal Count 31 2011-2012 86 2013-2014 87 SCHOOL RECORDS/TOP TIMES LISTS 2014-2015 88 School Records 32 2016-2017 89 Freshman Records 33 2017 90 Women’s Top Indoor Marks 34 Women’s Top Outdoor Marks 35 FACILITIES & RECORDS -

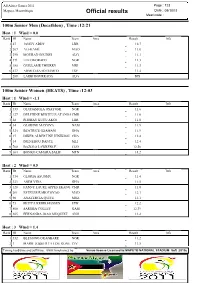

Official Results Date : 09/10/11 Meet Code

All Africa Games 2011 Page : 123 Maputo, Mozambique Official results Date : 09/10/11 Meet code : 100m Senior Men (Decathlon) , Time :12:21 Heat : 1 Wind = 0.0 Rank ID Name Team Area Result Info 1 27 JANGY ADDY LBR 10.7 2 207 ALI-KAMÉ MAD 11.0 3 290 MOURAD SOUISSI ALG 11.1 4 371 LEE OKORAFO NGR 11.3 5 185 GUILLAME THIERRY MRI 11.3 6 477 AHMED SAAD HAMED EGP 11.4 289 LARBI BOURRADA ALG DIS 100m Senior Women (HEATS) , Time :12:03 Heat : 1 Wind = -1.1 Rank ID Name Team Area Result Info 1 333 OLUDAMOLA OSAYOMI NGR 11.6 2 127 DELPHINE BERTILLE ATANGA CMR 11.6 3 28 PHOBAY KUTU AKOI LBR 11.8 4 34 GLOBINE MAYOVA NAM 11.9 5 324 BEATRICE GZAMANI GHA 11.9 6 17 DIKER ALBERTINE HINIKISSI CHA 12.4 7 14 DJENEBOU DANTE MLI 12.4 8 700 BAZOLO LAWRENCE COD 12.50 9 164 BONKO CAMARA SALIF MTN 14.2 Heat : 2 Wind = 0.5 Rank ID Name Team Area Result Info 1 334 GLORIA ASUNMU NGR 11.4 2 323 ANIM VIDA GHA 11.5 3 128 FANNY LAURE APPES EKANG CMR 11.8 4 201 ESTELLE RABOTOVAO MAD 12.1 5 96 ANATERCIA QUIVE MOZ 12.1 6 73 FETIYA KEDIR HASSEN ETH 12.2 7 800 SARUBA COLLEY GAM 12.39 8 305 FERNANDA JOAO MUQUIXT ANG 13.2 Heat : 3 Wind = 1.4 Rank ID Name Team Area Result Info 1 332 BLESSING OKAGBARE NGR 11.2 2 1 MARIE JOSSED TA LOU GONE CIV 11.5 Timing hardware and software : www.timetronics.be Venue license Licensed to:MAPUTO NATIONAL STADIUM Soft :2010u All Africa Games 2011 Page : 124 Maputo, Mozambique Official results Date : 09/10/11 Meet code : 3 129 CHARLOTTE MEBENGA AMO CMR 11.7 4 325 AGYAPONG FLINGS OWUSN GHA 11.8 5 170 MARIETTE MIEN BUR 12.2 6 410 JUSTIN BAYIGA UGA -

World Boxing Council Ratings

WORLD BOXING COUNCIL R A T I N G S RATINGS AS OF SEPTEMBER - 2018 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE SEPTIEMBRE - 2018 WORLD BOXING COUNCIL / CONSEJO MUNDIAL DE BOXEO COMITE DE CLASIFICACIONES / RATINGS COMMITTEE WBC Adress: Riobamba # 835, Col. Lindavista 07300 – CDMX, México Telephones: (525) 5119-5274 / 5119-5276 – Fax (525) 5119-5293 E-mail: [email protected] RATINGS RATINGS AS OF SEPTEMBER - 2018 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE SEPTIEMBRE - 2018 HEAVYWEIGHT (+200 - +90.71) CHAMPION: DEONTAY WILDER (US) EMERITUS CHAMPION: VITALI KLITSCHKO (UKRAINE) WON TITLE: January 17, 2015 LAST DEFENCE: March 3, 2018 LAST COMPULSORY: November 4, 2017 WBC SILVER CHAMPION: Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) WBC INT. CHAMPION: VACANT WBA CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) IBF CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) WBO CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) Contenders: WBO CHAMPION: Joseph Parker (New Zealand) WBO CHAMPION:WBO CHAMPION: Joseph Parker Joseph (New Parker Zealand) (New Zealand) 1 Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) SILVER Note: all boxers rated within the top 15 are 2 Luis Ortiz (Cuba) required to register with the WBC Clean 3 Tyson Fury (GB) * CBP/P Boxing Program at: www.wbcboxing.com 4 Dominic Breazeale (US) Continental Federations Champions: 5 Tony Bellew (GB) ABCO: 6 Joseph Parker (New Zealand) ABU: Tshibuabua Kalonga (Congo/Germany) BBBofC: Hughie Fury (GB) 7 Agit Kabayel (Germany) EBU CISBB: 8 Dereck Chisora (GB) EBU: Agit Kabayel (Germany) 9 Charles Martin (US) FECARBOX: 10 FECONSUR: Adam Kownacki (US) NABF: Oscar Rivas (Colombia/Canada) 11 Oscar Rivas (Colombia/Canada) NABF OPBF: Kyotaro Fujimoto (Japan) 12 Hughie Fury (GB) BBB C 13 Bryant Jennings (US) Affiliated Titles Champions: Commonwealth: Joe Joyce (GB) 14 Andy Ruiz Jr. -

Conclusion 60

Being Black, Being British, Being Ghanaian: Second Generation Ghanaians, Class, Identity, Ethnicity and Belonging Yvette Twumasi-Ankrah UCL PhD 1 Declaration I, Yvette Twumasi-Ankrah confirm that the work presented in this thesis is my own. Where information has been derived from other sources, I confirm that this has been indicated in the thesis. 2 Table of Contents Declaration 2 List of Tables 8 Abstract 9 Impact statement 10 Acknowledgements 12 Chapter 1 - Introduction 13 Ghanaians in the UK 16 Ghanaian Migration and Settlement 19 Class, status and race 21 Overview of the thesis 22 Key questions 22 Key Terminology 22 Summary of the chapters 24 Chapter 2 - Literature Review 27 The Second Generation – Introduction 27 The Second Generation 28 The second generation and multiculturalism 31 Black and British 34 Second Generation – European 38 US Studies – ethnicity, labels and identity 40 Symbolic ethnicity and class 46 Ghanaian second generation 51 Transnationalism 52 Second Generation Return migration 56 Conclusion 60 3 Chapter 3 – Theoretical concepts 62 Background and concepts 62 Class and Bourdieu: field, habitus and capital 64 Habitus and cultural capital 66 A critique of Bourdieu 70 Class Matters – The Great British Class Survey 71 The Middle-Class in Ghana 73 Racism(s) – old and new 77 Black identity 83 Diaspora theory and the African diaspora 84 The creation of Black identity 86 Black British Identity 93 Intersectionality 95 Conclusion 98 Chapter 4 – Methodology 100 Introduction 100 Method 101 Focus of study and framework(s) 103 -

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS of MARCH-APRIL 2006 Created on May 10Th, 2006 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O

WORLD BOXING ASSOCIATION GILBERTO MENDOZA PRESIDENT OFFICIAL RATINGS AS OF MARCH-APRIL 2006 th Created on May 10 , 2006 MEMBERS CHAIRMAN P.O. BOX 377 JOSE OLIVER GOMEZ E-mail: [email protected] JOSE EMILIO GRAGLIA (ARGENTINA) MARACAY 2101 -A ALAN KIM (KOREA) EDO. ARAGUA - VENEZUELA SHIGERU KOJIMA (JAPAN) PHONE: + (58-244) 663-1584 VICE CHAIRMAN GONZALO LOPEZ SILVERO (USA) + (58-244) 663-3347 GEORGE MARTINEZ E-mail: [email protected] MEDIA ADVISORS FAX: + (58-244) 663-3177 E-mail: [email protected] SEBASTIAN CONTURSI (ARGENTINA) Web site: www.wbaonline.com UNIFIED CHAMPION: O´NEIL BELL USA World Champion: NICOLAY VALUEV RUS Won Title: 01-07-06 World Champion: FABRICE TIOZZO FRA Won Title: 12-17 -05 Last Defense: Won Title: 03-20- 04 Last Mandatory: World Champion: VIRGIL HILL USA Last Mandatory: 02-26- 05 Last Defense: Won Title: 01 -27-06 Last Defense: 02-26- 05 Last Mandatory: WBC:HASIM RAHMAN - IBF:WLADIMIR KLITSCHKO Last Defense: WBC: THOMAS ADAMEK - IBF: CLINTON WOODS WBO : ZSOLT ERDEI WBO: SERGEI LIAKHOVICH WBC: O´NEIL BELL - IBF: VACANT WBO : JOHNNY NELSON 1. JOHN RUIZ USA 1. GUILLERMO JONE S (0C) PAN 1. SILVIO BRANCO (OC) ITA 2. RAY AUSTIN USA 2. JEAN MARC MORMECK FRA 2. MANNY SIACA P.R. 3. JAMES TONEY USA 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) 3. LUIS PINEDA (LAC) PAN 3. GLEN JOHNSON USA ( Over 200 Lbs / 90.71 Kgs) (175 Lbs / 79.38 Kgs) 4. PIETRO AURINO ITA 4. CALVIN BROCK USA 4. STEVE CUNNINGHAM USA l ( 5. RUSLAN CHAGAEV (WBA I/C) UZB 5. VALERY BRUDOV RUS 5. -

Annual Report 2019/2020 Financial Year

ANNUAL REPORT 2019/2020 FINANCIAL YEAR BOXING SOUTH AFRICA ANNUAL REPORT 2019/2020 FINANCIAL YEAR ANNUAL REPORT CONTENTS 2019/2020 FINANCIAL YEAR PART PART A General Information Performance Information B 1. Public Entity’s General Information 1. Auditor’s Report: Predetermined Objectives 2. List of Abbreviations/Acronyms 2. Situational Analysis 3. Foreword by the Chairperson 2.1. Service Delivery Environment 4. Chief Executive Officer’s Overview 2.2. Organisational Environment 5. Statement of Responsibility and Confirmation of 2.3. Key Policy Developments and Legislative Accuracy for the Annual Report Changes 6. Strategic Overview 3. Performance Information by Programme/Activity/ 6.1. Vision Objective 6.2. Mission 6.3. Values 3.1. Programme 1: Governance and Administration 7. Legislative and Other Mandates 3.2. Programme 2: Boxing Development 8. The Consolidated Mandate of BSA 3.3. Programme 3: Boxing Promotion 9. BSA Functions 10. Organisational Structure 4. Performance Against Predetermined Objectives 5. Revenue Collection PART PART C Governance Human Resource Management D 1. Introduction 1. Introduction 2. Executive Authority 2. Human Resource Oversight Statistics 3. The Accounting Authority 4. Risk Management 5. Internal Control Unit 6. Internal Audit and Audit Committees 7. Compliance with Laws and Regulations 8. Fraud and Corruption 9. inimising Conflict of Interest 10. Code of Conduct 11. Health, Safety and Environmental Issues 12. Social Responsibility 13. Audit Committee Report 14. B-BBBEE Compliance Performance Information PART -

Nomineees 181129

African Player of the year 1. Abdelmoumene Djabou (Algeria & ES Setif) 2. Ahmed Gomaa (Egypt & El Masry) 3. Ahmed Musa (Nigeria & Al-Nassr ) 4. Alex Iwobi (Nigeria & Arsenal) 5. Andre Onana (Cameroon & Ajax) 6. Anis Badri (Tunisia & Esperance) 7. Ayoub El Kaabi (Morocco & Hebei China Fortune) 8. Ben Malango (DR Congo & TP Mazembe) 9. Denis Onyango (Uganda & Mamelodi Sundowns) 10. Fanev Andriatsima (Madagascar & Clermont Foot) 11. Franck Kom (Cameroon & Esperance) 12. Jacinto Muondo Dala ‘Gelson’ (Angola & Primeiro de Agosto) 13. Hakim Ziyech (Morocco & Ajax) 14. Idrissa Gueye (Senegal & Everton) 15. Ismail Haddad (Morocco & Wydad Athletic Club) 16. Jean-Marc Makusu Mundele (DR Congo & AS Vita) 17. Kalidou Koulibaly (Senegal & Napoli) 18. Mahmoud Benhalib (Morocco & Raja Club Athletic) 19. Mehdi Benatia (Morocco & Juventus) 20. Mohamed Salah (Egypt & Liverpool) 21. Moussa Marega (Mali & Porto) 22. Naby Keita (Guinea & Liverpool) 23. Odion Ighalo (Nigeria & Changchun Yatai, Nigeria) 24. Percy Tau (South Africa & Union Saint-Gilloise) 25. Pierre-Emerick Aubameyang (Gabon & Arsenal) 26. Riyad Mahrez (Algeria & Manchester City) 27. Sadio Mane (Senegal & Liverpool) 28. Taha Khenissi (Tunisia & Esperance) 29. Thomas Partey (Ghana & Atletico Madrid) 30. Wahbi Khazri (Tunisia & Saint-Étienne) 31. Walid Soliman (Egypt & Ahly) 32. Wilfried Zaha (Cote d’Ivoire & Crystal Palace) 33. Yacine Brahimi (Algeria & Porto) 34. Youcef Belaili (Algeria & Esperance) CONFEDERATION AFRICAINE DE FOOTBALL 3 Abdel Khalek Tharwat Street, El Hay El Motamayez, P.O. Box 23 6th October City, Egypt - Tel.: +202 38247272/ Fax : +202 38247274 – [email protected] Women’s African player of the year 1. Abdulai Mukarama (Ghana & Northern Ladies) 2. Asisat Oshoala (Nigeria & Dilian Quanjian) 3. Bassira Toure (Mali & AS Mande) 4. -

Les Listes Des Finalistes Connues

Sport / Sports CAF AWARDS 2019 Les listes des finalistes connues C’est hier que la Confédération africaine de football (CAF) a dévoilé la liste finale et les nominés pour la cérémonie de la CAF Awards 2019 et la remise des trophées qui aura lieu le 7 janvier 2020 à Hurghada (Égypte). À cet effet, après avoir rendu publique une liste élargie de 10 joueurs, la CAF a retenu hier 3 joueurs pour le titre de meilleur joueur africain. Il s’agit du champion d’Afrique Riyad Mahrez (Manchester City), du Sénégalais Sadio Mané (Liverpool) et de l’Égyptien Mohamed Salah de Liverpool aussi. Pour le titre de meilleur entraîneur africain de l’année 2019, la CAF a désigné dans la liste finale 3 techniciens : Djamel Belmadi, champion d’Afrique avec l’Algérie ; Aliou Cissé, vice-champion d’Afrique avec le Sénégal ; alors que le troisième entraîneur n’est autre que le driver de l’Espérance de Tunis, champion d’Afrique des clubs avec l’EST la saison derrière, à savoir Mouine Chabaani. À propos du titre du jeune talent africain, 3 joueurs aussi ont été retenus : il s’agit du Marocain Achraf Hakimi, et des deux Nigérians Samuel Chukwueze et Victor Osimhen. L’Algérien Bennacer (22 ans) aurait pu figurer dans cette liste finale, étant donné qu’il est le meilleur joueur de la dernière Coupe d’Afrique des nations en Égypte, mais la CAF l’a désigné avec Riyad Mahrez dans la liste des nominés pour le meilleur joueur africain de l’année. En outre, 3 sélections ont été choisies pour le titre de la meilleure équipe africaine : l’Algérie (championne d’Afrique), le Sénégal (vice-champion d’Afrique) et Madagascar (la révélation de la CAN 2019). -

Athletics at the 1974 British Commonwealth Games - Wikipedia

28/4/2020 Athletics at the 1974 British Commonwealth Games - Wikipedia Athletics at the 1974 British Commonwealth Games At the 1974 British Commonwealth Games, the athletics events were held at the Queen Elizabeth II Park in Christchurch, Athletics at the 10th British New Zealand between 25 January and 2 February. Athletes Commonwealth Games competed in 37 events — 23 for men and 14 for women. Contents Medal summary Men Women Medal table The QE II Park was purpose-built for the 1974 Games. Participating nations Dates 25 January – 2 References February 1974 Host city Christchurch, New Medal summary Zealand Venue Queen Elizabeth II Park Men Level Senior Events 37 Participation 468 athletes from 35 nations Records set 1 WR, 18 GR ← 1970 Edinburgh 1978 Edmonton → 1974 British Commonwealth Games https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Athletics_at_the_1974_British_Commonwealth_Games 1/6 28/4/2020 Athletics at the 1974 British Commonwealth Games - Wikipedia Event Gold Silver Bronze 100 metres Don John Ohene 10.38 10.51 10.51 (wind: +0.8 m/s) Quarrie Mwebi Karikari 200 metres Don George Bevan 20.73 20.97 21.08 (wind: -0.6 m/s) Quarrie Daniels Smith Charles Silver Claver 400 metres 46.04 46.07 46.16 Asati Ayoo Kamanya John 1:43.91 John 800 metres Mike Boit 1:44.39 1:44.92 Kipkurgat GR Walker Filbert 3:32.16 John Ben 1500 metres 3:32.52 3:33.16 Bayi WR Walker Jipcho Ben 13:14.4 Brendan Dave 5000 metres 13:14.6 13:23.6 Jipcho GR Foster Black Dick Dave Richard 10,000 metres 27:46.40 27:48.49 27:56.96 Tayler Black Juma Ian 2:09:12 Jack Richard Marathon 2:11:19 -

World Boxing Council

xbp WORLD BOXING COUNCIL R A T I N G S RATINGS AS OF FEBRUARY - 2019 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE FEBRERO - 2019 WORLD BOXING COUNCIL / CONSEJO MUNDIAL DE BOXEO COMITE DE CLASIFICACIONES / RATINGS COMMITTEE WBC Adress: Riobamba # 835, Col. Lindavista 07300 – CDMX, México Telephones: (525) 5119-5274 / 5119-5276 – Fax (525) 5119-5293 E-mail: [email protected] RATINGS AS OF FEBRUARY - 2019 / CLASIFICACIONES DEL MES DE FEBRERO - 2019 HEAVYWEIGHT (+200 - +90.71) CHAMPION: DEONTAY WILDER (US) WON TITLE: January 17, 2015 LAST DEFENCE: December 1, 2018 LAST COMPULSORY: November 4, 2017 WBC SILVER CHAMPION: Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) WBC INT. CHAMPION: Filip Hrgovic (Croatia) IBF CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) WBO CHAMPION: Anthony Joshua (GB) Contenders: 1 Dillian Whyte (Jamaica/GB) SILVER Note: all boxers rated within the top 15 are 2 Tyson Fury (GB) required to register with the WBC Clean 3 Luis Ortiz (Cuba) Boxing Program at: www.wbcboxing.com 4 Dominic Breazeale (US) Continental Federations Champions: 5 Adam Kownacki (US) ABCO: ABU: Tshibuabua Kalonga (Congo/Germany) 6 Joseph Parker (New Zealand) BBBofC: Hughie Fury (GB) 7 CISBB: Alexander Povetkin (Russia) EBU: Agit Kabayel (Germany) 8 Agit Kabayel (Germany) EBU FECARBOX: Abigail Soto (Dom. R.) 9 FECONSUR: Kubrat Pulev (Bulgaria) NABF: Oscar Rivas (Colombia/Canada) 10 Oscar Rivas (Colombia/Canada) NABF OPBF: Kyotaro Fujimoto (Japan) 11 Carlos Takam (Cameroon) 12 Tony Yoka (France) * CBP/P Affiliated Titles Champions: 13 Commonwealth: Joe Joyce (GB) Dereck Chisora (GB) Continental Americas: 14 Charles Martin (US) Francophone: Dillon Carman (Canada) 15 Latino: Tyrone Spong (Surinam) Sergey Kuzmin (Russia) Mediterranean: Petar Milas (Croatia) USNBC: 16 Filip Hrgovic (Croatia) INTL YOUTH: Daniel Dubois (GB) 17 Joe Joyce (GB) COMM 18 NA= Not Available: Andy Ruiz Jr.