First Data on Canids Depredation on Livestock in an Area of Recent RECOLONIZATION by Wolf in Central Italy: Considerations on Conflict Survey and Prevention Methods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Aspetti Inventariali Dei Rimboschimenti Di Pino Nero in Provincia Di Rieti

Rivista italiana di Telerilevamento - 2008, 40 (1): 35-46 Aspetti inventariali dei rimboschimenti di pino nero in provincia di Rieti Andrea Lamonaca, Paolo Calvani, Diego Giuliarelli e Piermaria Corona Dipartimento di Scienze dell’Ambiente Forestale e delle sue Risorse, Università della Tuscia, via San Camillo de Lellis, 01100 Viterbo. E-mail: [email protected] Riassunto Durante il secolo scorso furono realizzati molti rimboschimenti di pino nero in ambito ap- penninico al fine di recuperare terreni degradati. Vari Autori hanno formulato proposte di gestione per la rinaturalizzazione di questi soprassuoli. La loro applicazione comporta però elevati costi di rilievo in sede di analisi. Obiettivo di questa nota è la proposizione di una metodologia di inventario ricognitivo degli attributi di questo tipo di soprassuoli che con- senta di ottenere dati sufficientemente attendibili su ampie superfici, a costi relativamente contenuti. A livello sperimentale è stata realizzata la mappatura dei rimboschimenti di pino nero della provincia di Rieti. La tecnica k-NN è stata utilizzata per spazializzare la provvi- gione legnosa a partire da aree di saggio a terra con l’ausilio di un’immagine telerilevata Landsat 7 ETM+. A scopo esemplificativo, gli aspetti inventariali sono integrati da misure ecologico-paesistiche per la descrizione spaziale dei rimboschimenti mappati. Parole chiave: inventari forestali, Landsat, ortofoto digitali, k-NN, provvigione legnosa Surveying black pine plantations in the province of Rieti (Italy) Abstract In the last century large afforestation programs were carried out in the Apennines to re- cover degraded lands, mainly by Pinus nigra plantations. Currently, many Authors have proposed management guidelines to foster the naturalization of such woodlands. -

25Th INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION of HOSPITAL ENGINEERING CONGRESS

25th INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF HOSPITAL ENGINEERING CONGRESS IFHE MAY 27-31 2018 RIETI INVITATION Bologna June 10 2018 Dear International Federation of Hospital Engineering, The SIAIS (Italian Society for Architecture and Engineer for Healthcare) would be honoured to host in 2018, the IFHE 25th Congress, in Italy . The SIAIS believes that the opportunity to have in Italy the 25th edition of the IFHE Congress should not be missed for the following reasons: first of all, Italy is absent from the international scene for a long time, second is that the recurrence of twenty-five years cannot fail to see Italy, which in 1970 hosted the 1st IFHE Congress, as the organizer of this important moment in science. The proposed conference location is Rieti the centre of Italy. The proposed dates in 2018, are : from Sunday, May 27 to Thursday, May 31. The official languages of the congress will be English and Italian, therefore simultaneous translation from Italian to English and vice versa will be guaranteed. Should a large group of delegates of a particular language be present it will be possible to arrange a specific simultaneous translation. May is a very pleasant month in Rieti with nice weather, still long sunny days and warm temperatures. Rieti is an Italian town of 47 927 inhabitants of Latium, capital of the Province of Rieti. Traditionally considered to be the geographical center of Italy, and this referred to as "Umbilicus Italiae", is situated in a fertile plain down the slopes of Mount Terminillo, on the banks of the river Velino. Founded at the beginning of the Iron Age, became the most important city of the Sabine people. -

The Long-Term Influence of Pre-Unification Borders in Italy

A Service of Leibniz-Informationszentrum econstor Wirtschaft Leibniz Information Centre Make Your Publications Visible. zbw for Economics de Blasio, Guido; D'Adda, Giovanna Conference Paper Historical Legacy and Policy Effectiveness: the Long- Term Influence of pre-Unification Borders in Italy 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regional development & globalisation: Best practices", 26-29 August 2014, St. Petersburg, Russia Provided in Cooperation with: European Regional Science Association (ERSA) Suggested Citation: de Blasio, Guido; D'Adda, Giovanna (2014) : Historical Legacy and Policy Effectiveness: the Long-Term Influence of pre-Unification Borders in Italy, 54th Congress of the European Regional Science Association: "Regional development & globalisation: Best practices", 26-29 August 2014, St. Petersburg, Russia, European Regional Science Association (ERSA), Louvain-la-Neuve This Version is available at: http://hdl.handle.net/10419/124400 Standard-Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Die Dokumente auf EconStor dürfen zu eigenen wissenschaftlichen Documents in EconStor may be saved and copied for your Zwecken und zum Privatgebrauch gespeichert und kopiert werden. personal and scholarly purposes. Sie dürfen die Dokumente nicht für öffentliche oder kommerzielle You are not to copy documents for public or commercial Zwecke vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, öffentlich zugänglich purposes, to exhibit the documents publicly, to make them machen, vertreiben oder anderweitig nutzen. publicly available on the internet, or to distribute or otherwise use the documents in public. Sofern die Verfasser die Dokumente unter Open-Content-Lizenzen (insbesondere CC-Lizenzen) zur Verfügung gestellt haben sollten, If the documents have been made available under an Open gelten abweichend von diesen Nutzungsbedingungen die in der dort Content Licence (especially Creative Commons Licences), you genannten Lizenz gewährten Nutzungsrechte. -

The Routes of Taste

THE ROUTES OF TASTE Journey to discover food and wine products in Rome with the Contribution THE ROUTES OF TASTE Journey to discover food and wine products in Rome with the Contribution The routes of taste ______________________________________ The project “Il Camino del Cibo” was realized with the contribution of the Rome Chamber of Commerce A special thanks for the collaboration to: Hotel Eden Hotel Rome Cavalieri, a Waldorf Astoria Hotel Hotel St. Regis Rome Hotel Hassler This guide was completed in December 2020 The routes of taste Index Introduction 7 Typical traditional food products and quality marks 9 A. Fruit and vegetables, legumes and cereals 10 B. Fish, seafood and derivatives 18 C. Meat and cold cuts 19 D. Dairy products and cheeses 27 E. Fresh pasta, pastry and bakery products 32 F. Olive oil 46 G. Animal products 48 H. Soft drinks, spirits and liqueurs 48 I. Wine 49 Selection of the best traditional food producers 59 Food itineraries and recipes 71 Food itineraries 72 Recipes 78 Glossary 84 Sources 86 with the Contribution The routes of taste The routes of taste - Introduction Introduction Strengthening the ability to promote local production abroad from a system and network point of view can constitute the backbone of a territorial marketing plan that starts from its production potential, involving all the players in the supply chain. It is therefore a question of developing an "ecosystem" made up of hospitality, services, products, experiences, a “unicum” in which the global market can express great interest, increasingly adding to the paradigms of the past the new ones made possible by digitization. -

Iscrizione Registro

AllegatoA) alladet. n. 462del 06/08/2012cornposio da n. 5 pagg. ISCRIZIONE REGISTRO Comuni del ISCRIZIONE Comp. NomeSquadra Capo-Squadra Comprensorio REGISTRO Il solengodi I ScarclaVito 2 Posta I F€datorì Angclinì Domenico 2 z Cittareale Luponem RossiGins€ppe 2 Posta-Cittarcale Le ven€ CalabreseDomerico 4 Borbom Tre monti TocchioFmnc€sco 2 Posta I tupi Marconi Francesco 6 2 Crttareale Vallannara Talianì Lùigi 7 2 Posta-Cìttarcale La pmtora Di Placido StefaÍo I lî scogio molro 3 MolrD Reatino Roselli Franco 9 Rivodùtf-Morro Torchio SampalmieriEnzo 10 Realino PoggioBustone Li Diaruri Rubimaúa Valterc t1 Sattamaria in 4 Marceteli De ArgelìsGaetarc 12 4 Marcetelli NtarceteIi Tolomei Antonio 4 Varco Sabirc segugio De SantisClaudìo l4 Bdganti del Fiamignaro Rotili Vi&enzo Pehella Salto Castellodi naéri Tolli Angelo 16 PetrellaSalto tr passatore2 De Massimi Adonio t1 5 PetrelìaSaÌo Peú€ÌaSaìto VutpianiGiusepp€ 18 PeÍella Salto Valle del salto RossiFmnco 19 PetrellaSalto La macchia Giodani Mario 20 Petlella Salto- 5 I segugio Giuli Lino Fiamisnarìo Rieti-Co[i Íl 6 II passatorcI Ciani À4arcello 22 Cinghialai 6 Greccio-Conîigliano Blasi Angelo 23 Grcccio Cinghialai 6 Gîeccio Scarciafraf€Ermatrno 24 Gr€c€io 6 Cortigliano-GreccioIl nrganlno Aguzzi Pierino 25 6 Contigliaro Valle tasso Natalid Arìselmo 26 6 Labro Aquita di labm Badid Marco 27 Cofi Sùl VeliÍo- 6 Col]i I Marchetti Labro Gianni 28 7 Solengo Dionisi Francesco 29 Cantalice-PogÉo Rapacidi cima 1 SEimts Felice 30 7 Leonessa Dialla C€sareailemando '| Lmtressa Pantem Cellinì SimoÍe 32 7 Leonessa -

Comune Indirizzo Denominazione Farmacia

ELENCO FARMACIE DI RIETI E PROVINCIA ( DPR 22.7.96 n.484 art.36 ) COMUNE INDIRIZZO DENOMINAZIONE TELEFONO FARMACIA ACCUMOLI Via Salaria, km 141,900 c/o COC Farmacia Del parco - Dr. Nigro 0746/840031 Francesco Anselmo AMATRICE centro commerciale triangolo Farmacia Cicconetti snc 0746/825214 AMATRICE area commerciale ex cotral Mauro sas 0746/826793 ANTRODOCO Piazza del Popolo, n. 13 Farmacia S.Anna snc 0746/578724 BORBONA Piazza Martiri IV Aprile, n. 1 D.ssa Giorgi Emanuela 0746/940121 BORGOROSE Viale Micangeli, n. 14 - Borgorose Farmacia Borgorose della D.ssa 0746/314547 Perni Paola BORGOROSE Via dello sport, n. 13/A - Corvaro Farmacia Dottori Perondi 0746/306152 BORGOVELINO Via M.L. King, snc Dr. Sciubba Belisario 0746/578261 CANTALICE Via Mazzini, n. 29 Farmacia Incandela - Dr. 0746/653315 Boccanera Pierluigi CANTALUPO IN S. Viale Verdi, n. 30 D.ssa Binaghi Alessandra 0765/514289 CASAPROTA Largo A. Filippi, n. 1 Farmacia Casaprota di De Rossi e 0765/85277 Fortuna snc CASPERIA Via Roma, n. 1 D.ssa Rizzuti Flavia 0765/63025 CASTEL DI TORA Via Turanense, n. 4 Dr. Caramagno Corrado 0765/716332 CASTEL SANT'ANGELO Via Nazionale I, n. 36 Farmacia Sant'Angelo - D.ssa Grillo 0746/698748 E. CASTELNUOVO DI FARFA Via Roma, n. 17-19 Dr. Conti Arcangelo 0765/36266 CITTADUCALE Piazza del Popolo, n. 10 Farmacia Domenici F. & C. sas 0746/602132 CITTADUCALE Via Don Mario D'Aquilio, snc – Santa Rufina A.S.M. n. 3 0746/694099 COLLALTO SABINO Via IV Novembre, n. 7 Dr. Colapietro Luca 0765/98298 COLLEVECCHIO Piazza V. Emanuele II, n. -

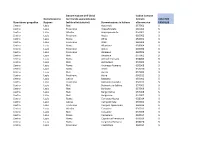

Allegato-F-Elenco-Comuni-Lazio

Denominazione dell'Unità Codice Comune Denominazione territoriale sovracomunale formato VOUCHER Ripartizione geografica Regione (valida a fini statistici) Denominazione in italiano alfanumerico FAMIGLIE Centro Lazio Rieti Accumoli 057001 SI Centro Lazio Frosinone Acquafondata 060001 SI Centro Lazio Viterbo Acquapendente 056001 SI Centro Lazio Frosinone Acuto 060002 SI Centro Lazio Roma Affile 058001 SI Centro Lazio Frosinone Alatri 060003 SI Centro Lazio Roma Allumiere 058004 SI Centro Lazio Frosinone Alvito 060004 SI Centro Lazio Frosinone Amaseno 060005 SI Centro Lazio Rieti Amatrice 057002 SI Centro Lazio Roma Anticoli Corrado 058006 SI Centro Lazio Rieti Antrodoco 057003 SI Centro Lazio Roma Arcinazzo Romano 058008 SI Centro Lazio Roma Arsoli 058010 SI Centro Lazio Rieti Ascrea 057004 SI Centro Lazio Frosinone Atina 060011 SI Centro Lazio Latina Bassiano 059002 SI Centro Lazio Frosinone Belmonte Castello 060013 SI Centro Lazio Rieti Belmonte in Sabina 057005 SI Centro Lazio Rieti Borbona 057006 SI Centro Lazio Rieti Borgo Velino 057008 SI Centro Lazio Rieti Borgorose 057007 SI Centro Lazio Roma Camerata Nuova 058014 SI Centro Lazio Latina Campodimele 059003 SI Centro Lazio Frosinone Campoli Appennino 060016 SI Centro Lazio Viterbo Canepina 056011 SI Centro Lazio Rieti Cantalice 057009 SI Centro Lazio Roma Canterano 058017 SI Centro Lazio Roma Capranica Prenestina 058019 SI Centro Lazio Roma Carpineto Romano 058020 SI Centro Lazio Frosinone Casalattico 060017 SI Centro Lazio Roma Casape 058021 SI Centro Lazio Rieti Casaprota 057011 -

Memoria Di Provincia. La Formazione Dell'archivio Di Stato Di Rieti E Le

· ( / PUBBLICAZIONI DEGLI ARCHIVI DI STAT O STRUMENTI CXXIX ROBERTO MARINELLI Memoria di provincia La formazione dell' Archivio di Stato di Rieti e le fonti storiche della regione sabina MINISTERO PER I BENI CULTURALI E AMBIENTALI UFFICIO CENTRALE PER I BENI ARCHIVISTICI 1996 UFFICIO CENTRALE PER I BENI ARCHIVISTICI DIVISIONE STUDI E PUBBLICAZIONI « ...1 manoscritti non bruciano ...» M. BULGAKOV, IlMaestro e Margherita, Torino, Einaudi, 1978 Direttore generale per i beni archivistici f.f.: Rosa Aronica Direttore della divisione studi e pubblicazioni: Antonio Dentoni-Litta «Appartiene alla natura dell'arte il pregio dell'integrità, inattaccabile perfino al fuoco, per niciosissimo tra tutti gli elementi cosmogonici. Questo intendeva dire Michail Bulgakov Comitato per le pubblicazioni: il direttore generale, presidente, Paola Carucci, Antonio ...Non fe ce in tempo a sapere quanto di personalmente profetico ci fo sse in quella perento Dentoni-Litta, Cosimo Damiano Fonseca, Romualdo Giuffrida, Lucio Lume, Enrica ria metafora ... Ormanni, Giuseppe Pansini, Claudio Pavone, Luigi Prosdocimi, Leopoldo Puncuh, ... Nel 1926 la polizia di stato gli perquisì la casa e gli confiscò il diario ... Antonio Romiti, Isidoro Soffietti, Isabella Zanni Rosiello, Lucia Fauci Moro, segretaria. ... Tre anni dopo gli riuscì di fa rsi restituire il mal tolto, e la prima cosa che fece fu di bru ciare il diario ... ... Ma sotto qualunque cielo e stendardo politico, la burocrazia è una macchina stipatrice capace, nella sua ottusità, di imbalsamare le indiscretezze -

Listino Dell'osservatorio Dei Valori Agricoli Provincia Di

ISSN: 2280-191X LIST INO DEI VA LORI IMMOB ILIARI DEI TE RRENI AGRI COLI PROVINCIA DI RIETI LISTINO 2020 RILEV AZIONE ANNO 2019 quotazioni dei valori di mercato dei terreni agricoli entro un minimo e un massimo per le principali colture in ciascun comune privati professionisti edizioni pubblica amministrazione OSSERVATORIO DEI VALORI AGRICOLI–PROVINCIA DI RIETI–RILEVAZIONE 2019 Hanno collaborato alla formazione del listino ALESSANDRA CURATOLO, si interessa di aspetti immobiliari e tecnici valutativi. È componente del Comitato degli esperti del Movimento Azzurro di Ardea. È coautore del libro dal titolo: “La stima dei terreni: agricoli ed edificabili” -Casa Editrice DEI s.r.l - Ha redatto vari articoli di contenuto immobiliare sulla rivista Case e Terreni di Bergamo e i seguenti articoli pubblicati sul sito internet www.Hausere.eu quali “Il rapporto immobiliare e le note semestrali dell’Agenzia del territorio: la costituzione di un indice immobiliare”, “La ripartizione delle spese nelle locazioni”, “Nuovo indicatore del mercato Immobiliare:l’indice delle nuove costruzioni”, l’articolo:“Il sottosuolo appartiene al condominio”. ANTONIO IOVINE, ingegnere libero professionista consulente in materia di catasto ed estimo, attualmente membro della Commissione Provinciale espropri di Roma. È stato dirigente dell’Agenzia del territorio, responsabile dell’Area per i servizi catastali della Direzione centrale cartografia, catasto e pubblicità immobiliare, membro della Commissione Censuaria Centrale. Autore/coautore di vari testi in materia di catasto, topografia ed estimo, ha svolto numerosi incarichi di docenza per formazione in materia di estimo, espropriazioni e catasto. La redazione gradisce indicazioni costruttive o suggerimenti migliorativi ([email protected]). Disclaimer L’elaborazione del testo, anche se curata con scrupolosa attenzione, non può comportare specifiche responsabilità per errori o inesattezze. -

TORNO SUBITO 2017” Programme of Actions for University Students and Graduates

“TORNO SUBITO 2017” Programme of actions for university students and graduates Call for the submission of applications Axis III- Education and Training Investment priority 10.ii, Specific objective 10.5 REGIONE LAZIO Regional Department for Training, Research, Schools and Universities Regional Management for Training, Research and Innovation Schools and Universities, Right to Education Programming Area for Training and Orientation Implementation of Operational Programme of the Lazio European Social Fund Programming period 2014-2020 Axis III- Education and training Investment priority 10.ii, Specific objective 10.5 Beneficiary: Laziodisu Organisation for the Right to University Education in Lazio “Torno Subito 2017” Programme of initiatives for university students and graduates A CALL FOR THE SUBMISSION OF APPLICATIONS “TORNO SUBITO 2017” Programme of actions for university students and graduates Call for the submission of applications Axis III- Education and Training Investment priority 10.ii, Specific objective 10.5 Premessa Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................... 3 Legislation references and definitions ...................................................................................................... 4 Articolo 1- Aim and structure of the initiative ....................................................................................... 8 Articolo 2- Available resources ................................................................................................................... -

AVVISO PUBBLICO Prot

DISTRETTO SOCIALE DELLA BASSA SABINA AMBITO TERRITORIALE RI 2 Comuni di: Cantalupo in Sabina, Casperia, Collevecchio, Configni, Cottanello, Forano, Magliano Sabina, Mompeo, Montasola, Montebuono, Montopoli di Sabina, Poggio Catino, Poggio Mirteto, Roccantica, Salisano, Selci Sabino, Stimigliano, Tarano, Torri in Sabina, Vacone. Ente capofila: CITTA’ DI POGGIO MIRTETO AVVISO PUBBLICO prot. n. 1872 del 10 febbraio 2021 Indizione di una istruttoria di evidenza pubblica per l’individuazione di soggetti del Terzo settore, di cui all’art. 1 comma 5 della Legge 8 novembre 2000 n. 328, per la co-progettazione dello “Sportello distrettuale per la prevenzione del gioco d’azzardo patologico (GAP)” Amministrazione procedente: Città di Poggio Mirteto, ente capofila del Distretto sociale della Bassa Sabina – ambito territoriale RI/2 In esecuzione della Determinazione del responsabile dell’Ufficio di Piano n. 04 del 22 gennaio 2021 Pag. 1/14 - Ente: COMUNE DI MONTOPOLI SABINA Anno: 2021 Numero: 2072 Tipo: A Data: 11.02.2021 Ora: Cat.: 14 Cla.: 1 Fascicolo: Art. 1 - AMMINISTRAZIONE PROCEDENTE Città di Poggio Mirteto, ente capofila del Distretto sociale della Bassa Sabina – ambito territoriale RI/2 – P.zza Martiri della Libertà, 40 - 02047 Poggio Mirteto (RI), tel. 0765.444.053, email: [email protected] – pec: [email protected] Art. 2 - QUADRO NORMATIVO DI RIFERIMENTO 1. Legge 8 novembre 2000, n.328 “Legge quadro per la realizzazione del sistema integrato di interventi e servizi sociali”; 2. Art 1, comma 5 della Legge n. 328/2000, “Legge quadro per la realizzazione del sistema integrato di interventi e servizi sociali” dove si prevede che ”Alla gestione ed all'offerta dei servizi provvedono soggetti pubblici nonché, in qualità di soggetti attivi nella progettazione e nella realizzazione concertata degli interventi, organismi non lucrativi di utilità sociale, organismi della cooperazione, organizzazioni di volontariato, associazioni ed enti di promozione sociale, fondazioni, enti di patronato e altri soggetti privati. -

AVVISO PUBBLICO Ai Sensi Della Propria Determinazione N

DISTRETTO SOCIALE DELLA BASSA SABINA Ambito territoriale Rieti 2 Comuni di: Cantalupo in Sabina, Casperia, Collevecchio, Configni, Cottanello, Forano, Magliano Sabina, Mompeo, Montasola, Montebuono, Montopoli di Sabina, Poggio Catino, Poggio Mirteto, Roccantica, Salisano, Selci Sabino, Stimigliano, Tarano, Torri in Sabina, Vacone. ENTE CAPOFILA: COMUNE DI POGGIO MIRTETO prot. 3297 dell’11 marzo 2016 Piano sociale di Zona 2015; Misure 1. e 2. Servizi essenziali Servizio di Sostegno alla residenzialità AVVISO PUBBLICO ai sensi della propria determinazione n. 19 del 7 marzo 2016, visto il disciplinare approvato dal Comitato dei sindaci il 25 febbraio 2016 il responsabile ad interim dell'Ufficio di Piano comunica che entro il 15 aprile 2016 è possibile presentare la richiesta dei contributi economici destinati alla Integrazione delle rette di ricovero in strutture residenziali socio assistenziali annualità 2015 A. Destinatari e requisiti Possono accedere al beneficio le persone anziane ultrasessantacinquenni ospitate in strutture residenziali, pubbliche e private, autorizzate ai sensi della L.R. 41/2003 e della DGR del Lazio n.1305/2004 e loro modifiche ed integrazioni e che abbiano la residenza anagrafica nel Distretto Sociale, ovvero nei comuni di: Cantalupo in Sabina, Casperia, Collevecchio, Configni, Cottanello, Forano, Magliano Sabina, Mompeo, Montasola, Montebuono, Montopoli di Sabina, Poggio Catino, Poggio Mirteto, Roccantica, Salisano, Selci, Stimigliano, Tarano, Torri in Sabina, Vacone. Nel caso in cui la residenza anagrafica sia presso la struttura, possono accedere al contributo le persone che nell’anno precedente siano state residenti in uno dei Comuni sopra elencati. L’anziano provvede al proprio mantenimento presso la struttura, fino a copertura della retta, con tutto il reddito percepito derivante da trattamenti economici di qualsiasi natura in godimento e decurtato di una franchigia mensile pari al 25% della quota mensile del minimo vitale.