Montaigne and the Origins of Modern Philosophy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

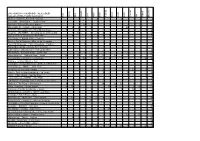

Template EUROVISION 2021

Write the names of the players in the boxes 1 to 4 (if there are more, print several times) - Cross out the countries that have not reached the final - Vote with values from 1 to 12, or any others that you agree - Make the sum of votes in the "TOTAL" column - The player who has given the highest score to the winning country will win, and in case of a tie, to the following - Check if summing your votes you’ve given the highest score to the winning country. GOOD LUCK! 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Anxhela Peristeri “Karma” Albania Montaigne “ Technicolour” Australia Vincent Bueno “Amen” Austria Efendi “Mata Hari” Azerbaijan Hooverphonic “ The Wrong Place” Belgium Victoria “Growing Up is Getting Old” Bulgaria Albina “Tick Tock” Croatia Elena Tsagkrinou “El diablo” Cyprus Benny Christo “ Omaga “ Czech Fyr & Flamme “Øve os på hinanden” Denmark Uku Suviste “The lucky one” Estonia Blind Channel “Dark Side” Finland Barbara Pravi “Voilà” France Tornike Kipiani “You” Georgia Jendrick “I Don’t Feel Hate” Germany Stefania “Last Dance” Greece Daði og Gagnamagnið “10 Years” Island Leslie Roy “ Maps ” Irland Eden Alene “Set Me Free” Israel 1 2 3 4 TOTAL Maneskin “Zitti e buoni” Italy Samantha Tina “The Moon Is Rising” Latvia The Roop “Discoteque” Lithuania Destiny “Je me casse” Malta Natalia Gordienko “ Sugar ” Moldova Vasil “Here I Stand” Macedonia Tix “Fallen Angel” Norwey RAFAL “The Ride” Poland The Black Mamba “Love is on my side” Portugal Roxen “ Amnesia “ Romania Manizha “Russian Woman” Russia Senhit “ Adrenalina “ San Marino Hurricane “LOCO LOCO” Serbia Ana Soklic “Amen” Slovenia Blas Cantó “Voy a quedarme” Spain Tusse “ Voices “ Sweden Gjon’s Tears “Tout L’Univers” Switzerland Jeangu Macrooy “ Birth of a new age” The Netherlands Go_A ‘Shum’ Ukraine James Newman “ Embers “ United Kingdom. -

Introduction

© Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. Introduction This is first an essay about emotions and attitudes that include some estimate of the self, such as pride, self-esteem, vanity, arro- gance, shame, humility, embarrassment, resentment, and indigna- tion. It is also about some qualities that bear on these emotions: our integrity, sincerity, or authenticity. I am concerned with the way these emotions and qualities manifest themselves in human life in general, and in the modern world in particular. The essay is therefore what the great German philosopher Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), never afraid of a grand title, would have called an exercise in pragmatic anthropology: Physiological knowledge of the human being concerns the investiga- tion of what nature makes of the human being; pragmatic, the inves- tigation of what he as a free-acting being makes of himself, or can and should make of himself.1 Kant here echoes an older theological tradition that while other animals have their settled natures, human beings are free to make For general queries, contact [email protected] Blackburn.indb 1 1/2/2014 1:21:37 PM © Copyright, Princeton University Press. No part of this book may be distributed, posted, or reproduced in any form by digital or mechanical means without prior written permission of the publisher. 2 INTRODUCTION of themselves what they will. So this book is about what we make of ourselves, or can and should make of ourselves. -

LES || VIES Des Hommes || Illustres, Grecs Et

BnF Archives et manuscrits LES || VIES des Hommes || illustres, Grecs et || Romains, comparees l'une || auec l'autre par Plutarque || de Chæronee, || Translatees premierement de Grec en François par mai- || stre Iaques Amyot lors Abbé de Bellozane, & depuis || en ceste troisieme edition reueuës & corrigees en in- || finis passages par le mesme Translateur, maintenant || Abbé de sainct Corneille de Compiegne, Conseiller || du Roy, & grand Aumosnier de France, à l'aide de || plusieurs exemplaires uieux escripts à la main, & aussi || du iugement de quelques personnages excellents en || sçauoir. || A Paris. || Par Vascosan Imprimeur du Roy. || M.D.LXVII [1567]. || Auec Priuilege. 6 vol. in-8. — LES || VIES de Hannibal, || et Scipion l'Afri- || cain, traduittes par Char- || les De-l'Ecluse. || A Paris, || Par Vascosan Imprimeur du Roy. || M.D.LXVII [1567]. In-8 de 150 p. et 1 f. blanc. — LES || OEVVRES || MORALES ET MESLEES || de Plutarque, Translatees de Grec || en François, reueuës & corrigees || en ceste seconde Edition || en plusieurs passages || par le Trans- || lateur. || .... || A Paris, || Par Vascosan Imprimeur du Roy. || M.D.LXXIIII [1574]. || Auec Priuilege. 6 vol. in-8. — TABLE tresample des || Noms et Choses notables, || contenuës en tous les Opuscules de Plu- || tarque. In-8. — Ensemble 14 part, en 13 vol. in-8. Cote : Rothschild 1899 [IV, 8(bis), 7-19] Réserver LES || VIES des Hommes || illustres, Grecs et || Romains, comparees l'une || auec l'autre par Plutarque || de Chæronee, || Translatees premierement de Grec en François par mai- || stre Iaques Amyot lors Abbé de Bellozane, & depuis || en ceste troisieme edition reueuës & corrigees en in- || finis passages par le mesme Translateur, maintenant || Abbé de sainct Corneille de Compiegne, Conseiller || du Roy, & grand Aumosnier de France, à l'aide de || plusieurs exemplaires uieux escripts à la main, & aussi || du iugement de quelques personnages excellents en || sçauoir. -

Descartes' Bête Machine, the Leibnizian Correction and Religious Influence

University of South Florida Digital Commons @ University of South Florida Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 4-7-2010 Descartes' Bête Machine, the Leibnizian Correction and Religious Influence John Voelpel University of South Florida Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Philosophy Commons Scholar Commons Citation Voelpel, John, "Descartes' Bête Machine, the Leibnizian Correction and Religious Influence" (2010). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. https://digitalcommons.usf.edu/etd/3527 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ University of South Florida. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Descartes’ Bête Machine, the Leibnizian Correction and Religious Influence by John Voelpel A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Martin Schönfeld, Ph.D. Roger Ariew, Ph.D. Stephen Turner, Ph.D. Date of Approval: April 7, 2010 Keywords: environmental ethics, nonhuman animals, Montaigne, skepticism, active force, categories © Copyright 2010, John W. Voelpel 040410 Note to Reader: Because the quotations from referenced sources in this paper include both parentheses and brackets, this paper uses braces “{}” in any location {inside or outside of quotations} for the writer’s parenthetical-like additions in both text and footnotes. 040410 Table of Contents Abstract iii I. Introduction 1 II. Chapter One: Montaigne: An Explanation for Descartes’ Bête Machine 4 Historical Environment 5 Background Concerning Nonhuman Nature 8 Position About Nature Generally 11 Position About Nonhuman Animals 12 Influence of Religious Institutions 17 Summary of Montaigne’s Perspective 20 III. -

Illinois Classical Studies

i 11 Parallel Lives: Plutarch's Lives, Lapo da Castiglionchio the Younger (1405-1438) and the Art of Italian Renaissance Translation CHRISTOPHER S. CELENZA Before his premature death in 1438 of an outbreak of plague in Ferrara, the Florentine humanist and follower of the papal curia Lapo da Castiglionchio the Younger left behind three main bodies of work in Latin, all still either unedited or incompletely edited: his own self-collected letters, a small number of prose treatises, and a sizeable corpus of Greek-to-Latin translations. This paper concerns primarily the last of these three aspects of his work and has as its evidentiary focus two autograph manuscripts that contain inter alia final versions of Lapo's Latin translations of Plutarch's Lives of Themistocles, Artaxerxes, and Aratus. In addition, however, to studying Lapo's translating techniques, this paper will address chiefly the complexities of motivation surrounding Lapo's choice of dedicatees for these translations. The range of circumstances will demonstrate, I hope, the lengths to which a young, little-known humanist had to go to support himself in an environment where there was as yet no real fixed, institutional place for a newly created discipline. Lapo and Translation: Patronage, Theory, and Practice Of the three areas mentioned, Lapo's translations represent the most voluminous part of his oeuvre and in fact it is to his translations that he owes his modem reputation. But why did this young humanist devote so much energy to translating? And why were Plutarch's Lives such an important part of his effort? An earlier version of this paper was delivered as an Oldfather Lecture at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign on 8 November 1996. -

![Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -In Memoriam]Ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998)](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7141/montaignes-unknown-god-and-melvilles-confidence-man-in-memoriam-ohn-spencer-hill-1943-1998-977141.webp)

Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -In Memoriam]Ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998)

CAMILLE R. LA Bossr:ERE The World Revolves Upon an I: Montaigne's Unknown God and Melville's Confidence-Man -in memoriam]ohn Spencer Hill (1943-1998) Les mestis qui ont ... le cul entre deux selles, desquels je suis ... I The mongrel! sorte, of which I am one ... sit betweene two stooles -Michel de Montaigne, "Des vaines subtilitez" I "Of Vaine Subtilties" Deus est anima brutorum. -Oliver Goldsmith, "The Logicians Refuted" YEA AND NAY EACH HATH HIS SAY: BUT GOD HE KEEPS THF MTDDT.F WAY -Herman Melville, "The Conflict of Convictions" T ATE-MODERN SCHOLARLY accounts of Montaigne and his L oeuvre attest to the still elusive, beguilingly ironic character of his humanism. On the one hand, the author of the Essais has in vited recognition as "a critic of humanism, as part of a 'Counter Renaissance'."' The wry upending of such vanity as Protagoras served to model for Montaigne-"Truely Protagoras told us prettie tales, when he makes man the measure of all things, who never knew so much as his owne," according to the famous sentence 1 Peter Burke, Montaigne (Oxford: Oxford UP, 1981) 11. 340 • THE DALHOUSIE REvlEW from the "Apologie of Raimond Sebond"2-naturally comes to mind when he is thought of in this way (Burke 12). On the other hand, Montaigne has been no less justifiably recognized by a long line of twentieth-century commentators3 as a major contributor to the progress of an enduring philosophy "qui fait de l'homme, selon la tradition antique, la valeur premiere et vise a son plein epa nouissement. -

P E Ti Is Tv Á N O Rs I L Á S Z Ló L E V I a Ttila B E Tti P . R O B I

n e i s l b ó l e m n l i i o i i z u a f o z i i á i t s l b s t i t R ESC HUNGARY RAJONGÓI TALÁLKOZÓ c b s v ó s i v z t t t r s o e t e . r i s a á e s m 2021-08-28 HELYSZÍNI SZAVAZÁS P I O L L A B P E Z R T I P Ö Albánia – Anxhela Peristeri – Karma 3 2 1 3 9 Ausztrália – Montaigne – Technicolour 5 5 Ausztria – Vincent Bueno – Amen 10 2 2 14 Azerbajdzsán – Efendi – Mata Hari 1 1 5 8 7 10 6 38 Belgium – Hooverphonic – The Wrong Place 6 4 3 6 19 Bulgária – VICTORIA – Growing Up Is Getting Old 7 10 7 7 6 4 41 Ciprus – Elena Tsagrinou – El Diablo 3 4 3 3 4 3 2 22 Csehország – Benny Cristo – omaga 0 Dánia – Fyr & Flamme – Øve os på hinanden 1 1 Egyesült Királyság – James Newman – Embers 5 6 1 12 Észak-Macedónia – Vasil – Here I Stand 0 Észtország – Uku Suviste – The Lucky One 7 4 11 Finnország – Blind Channel – Dark Side 2 2 8 12 Franciaország – Barbara Pravi – Voilà 10 12 12 12 12 12 4 3 2 79 Görögország – Stefania – Last Dance 12 4 5 2 6 10 39 Grúzia – Tornike Kipiani – You 0 Hollandia – Jeangu Macrooy – Birth of a New Age 8 7 4 19 Horvátország – Albina – Tick-Tock 7 2 8 17 Írország – Lesley Roy – Maps 2 5 12 8 27 Izland – Daði og Gagnamagnið – 10 Years 7 6 3 5 1 22 Izrael – Eden Alene – Set Me Free 1 3 2 6 Lengyelország – RAFAŁ – The Ride 8 7 15 Lettország – Samanta Tīna – The Moon Is Rising 1 1 Litvánia – The Roop – Discoteque 4 5 8 10 10 10 4 51 Málta – Destiny – Je me casse 8 10 12 4 6 10 50 Moldova – Natalia Gordienko – Sugar 5 10 8 23 Németország – Jendrik – I Don’t Feel Hate 0 Norvégia – TIX – Fallen Angel 0 Olaszország – Måneskin -

Descriptions of Sections

Fall 2009 LEH300-LEH301 Descriptions LEH300 Anderson, Jazz and the Improvised Arts A history of jazz music from New Orleans to New York is coupled with an examination James of improvisation in the arts. The class will investigate form and free creativity as applied to jazz, music from around the world, the visual arts, drama, and literature. LEH300 Ansaldi, The Doctor-Patient Relationship: In this course, participants will explore the complexities of the doctor-patient Pamela Viewed through Art and Science relationship by examining selected works of literature, medicine, psychology and art. To the doctor, illness is an analysis of blood tests, radiological images and clinical observations. To the patient, illness is a disrupted life. To the doctor, the disease process must be measured and charted. To the patient, disease is unfamiliar terrain—he or she looks to the doctor to provide a compass. The doctor may give directions, but the patient for various reasons may not follow them. Or, the doctor may give the wrong directions, leaving the patient to wander in circles, feeling lost and alone. Sometimes two doctors can give identical protocols to the same patient, but only one doctor can provide a cure. The surgeon wants to cut out the injured part; the patient wants to retain it at any cost. The physician diagnoses with a linear understanding of illness; the patient may see the sequencing of events leading up to the illness in a different order, which might lead to a different diagnosis. The twists and turns of doctor-patient communication can be dizzying…and the patient goes from doctor to doctor seeking clarity and a possible cure. -

2021 Country Profiles

Eurovision Obsession Presents: ESC 2021 Country Profiles Albania Competing Broadcaster: Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSh) Debut: 2004 Best Finish: 4th place (2012) Number of Entries: 17 Worst Finish: 17th place (2008, 2009, 2015) A Brief History: Albania has had moderate success in the Contest, qualifying for the Final more often than not, but ultimately not placing well. Albania achieved its highest ever placing, 4th, in Baku with Suus . Song Title: Karma Performing Artist: Anxhela Peristeri Composer(s): Kledi Bahiti Lyricist(s): Olti Curri About the Performing Artist: Peristeri's music career started in 2001 after her participation in Miss Albania . She is no stranger to competition, winning the celebrity singing competition Your Face Sounds Familiar and often placed well at Kënga Magjike (Magic Song) including a win in 2017. Semi-Final 2, Running Order 11 Grand Final Running Order 02 Australia Competing Broadcaster: Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) Debut: 2015 Best Finish: 2nd place (2016) Number of Entries: 6 Worst Finish: 20th place (2018) A Brief History: Australia made its debut in 2015 as a special guest marking the Contest's 60th Anniversary and over 30 years of SBS broadcasting ESC. It has since been one of the most successful countries, qualifying each year and earning four Top Ten finishes. Song Title: Technicolour Performing Artist: Montaigne [Jess Cerro] Composer(s): Jess Cerro, Dave Hammer Lyricist(s): Jess Cerro, Dave Hammer About the Performing Artist: Montaigne has built a reputation across her native Australia as a stunning performer, unique songwriter, and musical experimenter. She has released three albums to critical and commercial success; she performs across Australia at various music and art festivals. -

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Atypical Lives: Systems of Meaning in Plutarch's Theseus-Romulus Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/6f213297 Author Street, Joel Martin Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Atypical Lives: Systems of Meaning in Plutarch's Teseus-Romulus by Joel Martin Street A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Classics in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Professor Dylan Sailor Professor Ramona Naddaff Fall 2015 Abstract Atypical Lives: Systems of Meaning in Plutarch's Teseus-Romulus by Joel Martin Street Doctor of Philosophy in Classics University of California, Berkeley Professor Mark Griffith, Chair Tis dissertation takes Plutarch’s paired biographies of Teseus and Romulus as a path to understanding a number of roles that the author assumes: as a biographer, an antiquarian, a Greek author under Roman rule. As the preface to the Teseus-Romulus makes clear, Plutarch himself sees these mythological fgures as qualitatively different from his other biographical sub- jects, with the consequence that this particular pair of Lives serves as a limit case by which it is possible to elucidate the boundaries of Plutarch’s authorial identity. Tey present, moreover, a set of opportunities for him to demonstrate his ability to curate and present familiar material (the founding of Rome, Teseus in the labyrinth) in demonstration of his broad learning. To this end, I regard the Teseus-Romulus as a fundamentally integral text, both of whose parts should be read alongside one another and the rest of Plutarch’s corpus rather than as mere outgrowths of the tra- ditions about the early history of Athens and Rome, respectively. -

Giordano Bruno and Michel De Montaigne

Journal of Early Modern Studies, n. 6 (2017), pp. 157-181 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.13128/JEMS-2279-7149-20393 (Re)thinking Time: Giordano Bruno and Michel de Montaigne Rachel Ashcroft Durham University (<[email protected]>) Abstract The article seeks to illustrate how the theme of time may be a worthwhile starting point towards uncovering useful connections between the philosophy of Giordano Bruno and that of Michel de Montaigne. Firstly, a brief literature review will assess the admittedly small but promising criticism that has previously attempted to bring the two writers together. Subsequently, the article argues that time is a meaningful way to approach their texts. Specifically, time refers to the drama that arises between the material body, which generally exists within a so-called natural order of time, and the mind which is not tied to the present moment, and is free to contemplate both past and future time. The article argues that Bruno and Montaigne’s understanding of time in this manner leads them to question traditional representations of time, such as the common fear of death, in remarkably similar ways. This process will be illustrated through examples drawn from two chapters of the Essais and a dialogue from the Eroici furori, and will conclude by assessing the straightforward connections that have arisen between the two authors, as well as scope for further research in this area. Keywords: Giordano Bruno, Michel de Montaigne, Sixteenth Century, Time 1. Introduction In recent years, a small number of critics have attempted to establish significant biographical and intellectual connections between Giordano Bruno and Michel de Montaigne. -

Taking Centre Stage: Plutarch and Shakespeare

chapter 29 Taking Centre Stage: Plutarch and Shakespeare Miryana Dimitrova William Shakespeare (1564–1616) was familiar with various classical sources but it was Plutarch’s Lives of the noble Greeks and Romans that played a de- cisive role in the shaping of his Roman plays. The Elizabethan Julius Caesar (performed probably at the opening of the Globe theatre in 1599), and the Jacobean Antony and Cleopatra (c. 1606–1607) and Coriolanus (c. 1605–1610) are almost exclusively based on the Lives, while numerous other plays have been thematically influenced by the Plutarchan canon or include references to specific works. Although modern scholarship generally recognises Shakespeare’s knowl- edge of Latin (ultimately grounded in the playwright’s grammar school educa- tion, which included canonical texts in its curriculum) as well as French and Italian,1 it is widely accepted that he used Sir Thomas North’s translation of the Plutarch’s Lives. Ubiquitously dubbed “Shakespeare’s Plutarch”, its first edi- tion in the English vernacular appeared in 1579 and was followed by expanded editions in 1595 and 1603. North translated the Lives from the French version of Jacques Amyot, published in 1559 (see Frazier-Guerrier and Lucchesi in this volume). Shakespeare was also acquainted with the Moralia, possibly in its first English translation by Philemon Holland published in 1603, although a version entered in the Stationers Register in 1600 allows for a possible influence on Shakespeare’s earlier works.2 Shakespeare’s borrowings should be seen in the light of the fact that Plutarch’s Lives were admired in early modern England for their profound in- terest in the complexities of the human character and their didactic signifi- cance.