Sample Download

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muhammad Ali: an Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America

Muhammad Ali: An Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Voulgaris, Panos J. 2016. Muhammad Ali: An Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33797384 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Muhammad Ali: An Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America Panos J. Voulgaris A Thesis in the Field of History for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2016 © November 2016, Panos John Voulgaris Abstract The rhetoric and life of Muhammad Ali greatly influenced the advancement of African Americans. How did the words of Ali impact the development of black America in the twentieth century? What role does Ali hold in history? Ali was a supremely talented artist in the boxing ring, but he was also acutely aware of his cultural significance. The essential question that must be answered is how Ali went from being one of the most reviled people in white America to an icon of humanitarianism for all people. He sought knowledge through personal experience and human interaction and was profoundly influenced by his own upbringing in the throes of Louisville’s Jim Crow segregation. -

Marvelous: the Marvin Hagler Story Online

vNdKG [Download free pdf] Marvelous: The Marvin Hagler Story Online [vNdKG.ebook] Marvelous: The Marvin Hagler Story Pdf Free Brian Hughes, Damian Hughes audiobook | *ebooks | Download PDF | ePub | DOC Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #1264795 in Books Hughes Brian 2016-11-01Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 8.00 x .80 x 5.00l, .57 #File Name: 178531145X240 pagesMarvelous The Marvin Hagler Story | File size: 40.Mb Brian Hughes, Damian Hughes : Marvelous: The Marvin Hagler Story before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Marvelous: The Marvin Hagler Story: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Marvelous MarvinBy hopefulGood read brings out the real Marvin to those unfamiliar with his dogged will. Over 50 fights be a Championship shot, avoided, under paid left him with contempt and bile for Pretty boys and Superstars.6 of 6 people found the following review helpful. No Interaction with SubjectBy Michael W. Mc ManusMost info is from newspaper or secondary sources. Story is unimaginative but complete. Not a lot about how Marvelous Marvin is doing right now in Italy.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Good effortBy ihaschThis is a good, solid biography of my favorite boxer of all time. Hagler is a fighter whose stature grows with time. You look back on his career, on the tough road he had to the title, on the honest way he fought. The man was probably the last of his kind. As others have noted, Hagler himself does not participate (maybe we will see an autobiography some day) but the book is well sourced and well written. -

The Epic 1975 Boxing Match Between Muhammad Ali and Smokin' Joe

D o c u men t : 1 00 8 CC MUHAMMAD ALI - RVUSJ The epic 1975 boxing match between Muhammad Ali and Smokin’ Joe Frazier – the Thriller in Manila – was -1- 0 famously brutal both inside and outside the ring, as a neW 911 documentary shows. Neither man truly recovered, and nor 0 did their friendship. At 64, Frazier shows no signs of forgetting 8- A – but can he ever forgive? 00 8 WORDS ADAM HIGGINBOTHAM PORTRAIT STEFAN RUIZ C - XX COLD AND DARK,THE BIG BUILDING ON of the world, like that of Ali – born Cassius Clay .pdf North Broad Street in Philadelphia is closed now, the in Kentucky – began in the segregated heartland battered blue canvas ring inside empty and unused of the Deep South. Born in 1944, Frazier grew ; for the first time in more than 40 years. On the up on 10 acres of unyielding farmland in rural Pa outside, the boxing glove motifs and the black letters South Carolina, the 11th of 12 children raised in ge that spell out the words ‘Joe Frazier’s Gym’ in cast a six-room house with a tin roof and no running : concrete are partly covered by a ‘For Sale’ banner. water.As a boy, he played dice and cards and taught 1 ‘It’s shut down,’ Frazier tells me,‘and I’m going himself to box, dreaming of being the next Joe ; T to sell it.The highest bidder’s got it.’The gym is Louis. In 1961, at 17, he moved to Philadelphia. r where Frazier trained before becoming World Frazier was taken in by an aunt, and talked im Heavyweight Champion in 1970; later, it would also his way into a job at Cross Brothers, a kosher s be his home: for 23 years he lived alone, upstairs, in slaughterhouse.There, he worked on the killing i z a three-storey loft apartment. -

K S Pwa Begins Lending, Spending; Approves Nearly

Member ot the Audit Bureau ot Ctrenlatlouu MANCHESTER — A aTY . OF VILLAGE CHARM VOL. LVIL (ClaealBed ,Adver|Hataig on Pagu U ) MANCHESTER, CONN, WEDNESDAY, JUNE 22, 1938 (FOURTEEN PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS « E R LAUDS JUDGE INGUS Japan Sets Up “No Man’s Land” ITALY AS PLANE MUST RULE ON KS PWA BEGINS LENDING, BOMBS 1 SHIPS iflso m c n o N SUBMIT PLEAS iini Keen Foi> Opera- In Novel Position From Pro- SPENDING; APPROVES Answer “Not GnUty” To tion Of Pact, Says Cham- test On Alcorn; 5 Defend- Charge Of Taking Bribe; berlain; Bomb Italy’s Is- ants Do Not File Motions NEARLY 300 PROJECTS Hickey To Plead Later To- land Base— ^Lloyd George In Tbe Brass City Cases. t day; Demurrer Ovemtled Spy-Hunting G-Man Resigns Over 41 MiOions In Grants London, June 22— (AP) —Prime Waterbury, June 22 — (AP) — Minister Chamberlain told the And Nine Millions In The legality of the appointment of Hartford. June 22— (A P )—State House of Commons today that Italy Hugh M. Alcorn as special prosecu- Senators Matthew A Daly of New waa anxious to put Into effect the tor before the Waterbury Grand Haven and Joseph H. Lawlor of Loans ADowed; Construe* Anglo-Itallan agreement covering Jury remained today a matter for Waterbury and Rep. John D. Thoma, Mediterranean Issues but denied Superior Court Judge Ernest A, that Rome was trying to “drive a also of Waterbury, pleaded innocent tion Work F ill Be Allo- Inglis, who himself made the ap- wedge” between Britain and France. pointment, to decide. -

BCN 205 Woodland Park No.261 Georgetown, TX 78633 September-October 2011

BCN 205 Woodland Park no.261 Georgetown, TX 78633 september-october 2011 FIRST CLASS MAIL Olde Prints BCN on the web at www.boxingcollectors.com The number on your label is the last issue of your subscription PLEASE VISIT OUR WEBSITE AT WWW.HEAVYWEIGHTCOLLECTIBLES.COM FOR RARE, HARD-TO-FIND BOXING ITEMS SUCH AS, POSTERS, AUTOGRAPHS, VINTAGE PHOTOS, MISCELLANEOUS ITEMS, ETC. WE ARE ALWAYS LOOKING TO PURCHASE UNIQUE ITEMS. PLEASE CONTACT LOU MANFRA AT 718-979-9556 OR EMAIL US AT [email protected] 16 1 JO SPORTS, INC. BOXING SALE Les Wolff, LLC 20 Muhammad Ali Complete Sports Illustrated 35th Anniver- VISIT OUR WEBSITE: sary from 1989 autographed on the cover Muhammad Ali www.josportsinc.com Memorabilia and Cassius Clay underneath. Recent autographs. Beautiful Thousands Of Boxing Items For Sale! autographs. $500 BOXING ITEMS FOR SALE: 21 Muhammad Ali/Ken Norton 9/28/76 MSG Full Unused 1. MUHAMMAD ALI EXHIBITION PROGRAM: 1 Jack Johnson 8”x10” BxW photo autographed while Cham- Ticket to there Fight autographed $750 8/24/1972, Baltimore, VG-EX, RARE-Not Seen Be- pion Rare Boxing pose with PSA and JSA plus LWA letters. 22 Muhammad Ali vs. Lyle Alzado fi ght program for there exhi- fore.$800.00 True one of a kind and only the second one I have ever had in bition fi ght $150 2. ALI-LISTON II PRESS KIT: 5/25/1965, Championship boxing pose. $7,500 23 Muhammad Ali vs. Ken Norton 9/28/76 Yankee Stadium Rematch, EX.$350.00 2 Jack Johnson 3x5 paper autographed in pencil yours truly program $125 3. -

In This Corner

Welcome UPCOMING Dear Friends, On behalf of my colleagues, Jerry Patch and Darko Tresnjak, and all of our staff SEA OF and artists, I welcome you to The Old TRANQUILITY Globe for this set of new plays in the Jan 12 - Feb 10, 2008 Cassius Carter Centre Stage and the Old Globe Theatre Old Globe Theatre. OOO Our Co-Artistic Director, Jerry Patch, THE has been closely connected with the development of both In This Corner , an Old Globe- AMERICAN PLAN commissioned script, and Sea of Tranquility , a recent work by our Playwright-in-Residence Feb 23 - Mar 30, 2008 Howard Korder, and we couldn’t be more proud of what you will be seeing. Both plays set Cassius Carter Centre Stage the stage for an exciting 2008, filled with new work, familiar works produced with new insight, and a grand new musical ( Dancing in the Dark ) based on a classic MGM musical OOO from the golden age of Hollywood. DANCING Our team plans to continue to pursue artistic excellence at the level expected of this IN THE DARK institution and build upon the legacy of Jack O’Brien and Craig Noel. I’ve had the joy and (Based on the classic honor of leading the Globe since 2002, and I believe we have been successful in our MGM musical “The Band Wagon”) attempt to broaden what we do, keep the level of work at the highest of standards, and make Mar 4 - April 13, 2008 certain that our finances are healthy enough to support our artistic ambitions. With our Old Globe Theatre Board, we have implemented a $75 million campaign that will not only revitalize our campus but will also provide critical funding for the long-term stability of the Globe for OOO future generations. -

Boxers of the 1940S in This Program, We Will Explore the Charismatic World of Boxing in the 1940S

Men’s Programs – Discussion Boxers of the 1940s In this program, we will explore the charismatic world of boxing in the 1940s. Read about the top fighters of the era, their rivalries, and key bouts, and discuss the history and cultural significance of the sport. Preparation & How-To’s • Print photos of boxers of the 1940s for participants to view or display them on a TV screen. • Print a large-print copy of this discussion activity for participants to follow along with and take with them for further study. • Read the article aloud and encourage participants to ask questions. • Use Discussion Starters to encourage conversation about this topic. • Read the Boxing Trivia Q & A and solicit answers from participants. Boxers of the 1940s Introduction The 1940s were a unique heyday for the sport of boxing, with some iconic boxing greats, momentous bouts, charismatic rivalries, and the introduction of televised matches. There was also a slowdown in boxing during this time due to the effects of World War II. History Humans have fought each other with their fists since the dawn of time, and boxing as a sport has been around nearly as long. Boxing, where two people participate in hand-to-hand combat for sport, began at least several thousand years ago in the ancient Near East. A relief from Sumeria (present-day Iraq) from the third millennium BC shows two facing figures with fists striking each other’s jaws. This is the earliest known depiction of boxing. Similar reliefs and paintings have also been found from the third and second millennium onward elsewhere in the ancient Middle East and Egypt. -

Come In-The Water's Fine

May 26, 1961 THE PHOENIX JEWISH NEWS Page 3 Final Scores JEWS IN SPORTS Boxing Story SPORT In Bowling HTie AfSinger BY HAROLD U. RIBALOW was the big night of Singer’s ca- reer. More than 35,000 fans crowd- SCOOP NEW YORK, (JTA)—The death ed into Yankee Stadium, paying By RONfclE PIES him in the 440. Throughout the of former lightweight the title fight be- gap. With 10 Announced last month $160,000 to see goal race Art closed the boxing champion A1 Singer was a tween Singer and the lightweight In keeping with the prime yards remaining, he passed his op- Final season scores in B'nai to all who follow the sport. champion, 26-year-old Sammy of this series, which is to give rec- ponent pulled away to win. blow the of Phoe- and B’rith bowling leagues have been Al Singer was known as a boxer Mandell. The champ was a ten- ognition to Jewish athletes TO COMPLETE his high school Singer nix and Arizona, we will honor a announced: with a “glass jaw.” This is an year veteran of the ring; career, Art was invited to a na- disease, which means three years of fighting different athlete in each article. tional championship meet in Los Majors league Carl Slonsky, occupational had only chosen that a man has a physical weak- behind him. The first person we have Angeles to compete with some of high individual series of 665; Jack the A shot at the jaw out cautiously, to honor is Art Gardenswartz, Uni- in the 269. -

Published, Despite Numerous Submissions Being Made

Studies in Arts and Humanities VOL07/ISSUE01/2021 ARTICLE | sahjournal.com Honour and Shame in Women’s Sports Katie Liston School of Sport, Ulster University Newtownabbey, Northern Ireland © Katie Liston. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Abstract This piece, first delivered as a keynote address, examines the role of honour and shame in understanding the many stories of women's involvement in sport in Ireland from the eighteenth century onwards, and especially in the modern era. While women's sporting involvement was regarded as shameful, especially in those sports imbued with traditional associated masculine norms, the prospect for women's sports is different today than in the past. Yet the struggle for honour is ongoing, seen in topical debates concerning gender quotas and the recommendations made by the Citizens Assembly on gender equality. Bringing the analysis up to date, the piece outlines hoc policy initiatives around gender equality in sport from the mid-2000s (in which the author was centrally involved) to the publication of the first formal statutory policy on women in sport, in 2019. Here it is argued that the guilt and shame of previous generations has influenced the public debate on gender quotas and it is as if, in the desire for perceived equality, the current generation of sportswomen do not wish to be associated with quotas. In this way, honour is conflated with merit. The piece concludes by suggesting that merit is honourable, personally, but equally, quotas are by no means shameful in public struggles. -

6 Diciembre 2015 Ingles.Cdr

THE DOORS TO LATIN AMERICA, arrival of the Spanish on the XVI Century. TIJUANA B.C. , HOST VENUE OF January 2016 will be an spectacular year, the second World Boxing Council female OUR NEXT FEMALE CONVENTION convention will be hosted on this magnificent place. “Here starts our homeland” that’s Tijuana´s motto, it is the first Latin America city that The greatest female fighters will travel to shares border with San Diega, US anf is the Tijuana with the main goal of spreading and fifth most populated city of Mexico having keep developing this sport as we are able to more than 1, 600,000 habitants on it. enjoy all of its cultural and historic attractions. Tijuana is a city of great commercial and cultural activity, its history began with the Editorial Index Future fights WBC Emerald Belt May-Pac Roman Gonzalez Golovkin Viktor Postol Jorge Linares Zulina Muñoz Mikaela Lauren Erica Farias Alicia Ashley Ibeth Zamora Yessica Chavez Soledad Matthysse Leo Santa Cruz becomes Diamond champion Francisco Vargas Directorio: Saul Alvarez “WBC Boxing World” is the official magazine of the World Boxing Council. Floyd´s final Hurrah . Executive Director WBC Cares Mauricio Sulaimán. WBC Annual Convention Subdirector Víctor Silva. Knowing a Champion: Deontay Wilder Marketing Manager José Antonio Arreola Sulaimán Muhammad Ali Honored Managing Editor Mauricio Sulaiman is presented with the keys to the Francisco Posada Toledo city of Miami Traducción PRESIDENT DANIEL ORTEGA: a great supporter of Paul Landeros / James Blears Nicaraguan boxing Design Director Alaín -

Fight Year Duration (Mins)

Fight Year Duration (mins) 1921 Jack Dempsey vs Georges Carpentier (23:10) 1921 23 1932 Max Schmeling vs Mickey Walker (23:17) 1932 23 1933 Primo Carnera vs Jack Sharkey-II (23:15) 1933 23 1933 Max Schmeling vs Max Baer (23:18) 1933 23 1934 Max Baer vs Primo Carnera (24:19) 1934 25 1936 Tony Canzoneri vs Jimmy McLarnin (19:11) 1936 20 1938 James J. Braddock vs Tommy Farr (20:00) 1938 20 1940 Joe Louis vs Arturo Godoy-I (23:09) 1940 23 1940 Max Baer vs Pat Comiskey (10:06) – 15 min 1940 10 1940 Max Baer vs Tony Galento (20:48) 1940 21 1941 Joe Louis vs Billy Conn-I (23:46) 1941 24 1946 Joe Louis vs Billy Conn-II (21:48) 1946 22 1950 Joe Louis vs Ezzard Charles (1:04:45) - 1HR 1950 65 version also available 1950 Sandy Saddler vs Charley Riley (47:21) 1950 47 1951 Rocky Marciano vs Rex Layne (17:10) 1951 17 1951 Joe Louis vs Rocky Marciano (23:55) 1951 24 1951 Kid Gavilan vs Billy Graham-III (47:34) 1951 48 1951 Sugar Ray Robinson vs Jake LaMotta-VI (47:30) 1951 47 1951 Harry “Kid” Matthews vs Danny Nardico (40:00) 1951 40 1951 Harry Matthews vs Bob Murphy (23:11) 1951 23 1951 Joe Louis vs Cesar Brion (43:32) 1951 44 1951 Joey Maxim vs Bob Murphy (47:07) 1951 47 1951 Ezzard Charles vs Joe Walcott-II & III (21:45) 1951 21 1951 Archie Moore vs Jimmy Bivins-V (22:48) 1951 23 1951 Sugar Ray Robinson vs Randy Turpin-II (19:48) 1951 20 1952 Billy Graham vs Joey Giardello-II (22:53) 1952 23 1952 Jake LaMotta vs Eugene Hairston-II (41:15) 1952 41 1952 Rocky Graziano vs Chuck Davey (45:30) 1952 46 1952 Rocky Marciano vs Joe Walcott-I (47:13) 1952 -

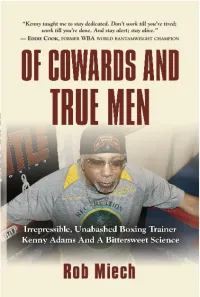

Of Cowards and True Men Order the Complete Book From

Kenny Adams survived on profanity and pugilism, turning Fort Hood into the premier military boxing outfit and coaching the controversial 1988 U.S. Olympic boxing team in South Korea. Twenty-six of his pros have won world-title belts. His amateur and professional successes are nonpareil. Here is the unapologetic and unflinching life of an American fable, and the crude, raw, and vulgar world in which he has flourished. Of Cowards and True Men Order the complete book from Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/8941.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Enjoy your free excerpt below! Of Cowards and True Men Rob Miech Copyright © 2015 Rob Miech ISBN: 978-1-63490-907-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., Bradenton, Florida, U.S.A. Printed on acid-free paper. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2015 First Edition I URINE SPRAYS ALL over the black canvas. A fully loaded Italian Galesi-Brescia 6.35 pearl-handled .25-caliber pistol tumbles onto the floor of the boxing ring. Just another day in the office for Kenny Adams. Enter the accomplished trainer’s domain and expect anything. “With Kenny, you never know,” says a longtime colleague who was there the day of Kenny’s twin chagrins. First off, there’s the favorite word. Four perfectly balanced syllables, the sweet matronly beginning hammered by the sour, vulgar punctuation.