The 7 Leader Questions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muhammad Ali: an Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America

Muhammad Ali: An Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Voulgaris, Panos J. 2016. Muhammad Ali: An Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America. Master's thesis, Harvard Extension School. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33797384 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Muhammad Ali: An Unusual Leader in the Advancement of Black America Panos J. Voulgaris A Thesis in the Field of History for the Degree of Master of Liberal Arts in Extension Studies Harvard University November 2016 © November 2016, Panos John Voulgaris Abstract The rhetoric and life of Muhammad Ali greatly influenced the advancement of African Americans. How did the words of Ali impact the development of black America in the twentieth century? What role does Ali hold in history? Ali was a supremely talented artist in the boxing ring, but he was also acutely aware of his cultural significance. The essential question that must be answered is how Ali went from being one of the most reviled people in white America to an icon of humanitarianism for all people. He sought knowledge through personal experience and human interaction and was profoundly influenced by his own upbringing in the throes of Louisville’s Jim Crow segregation. -

The Epic 1975 Boxing Match Between Muhammad Ali and Smokin' Joe

D o c u men t : 1 00 8 CC MUHAMMAD ALI - RVUSJ The epic 1975 boxing match between Muhammad Ali and Smokin’ Joe Frazier – the Thriller in Manila – was -1- 0 famously brutal both inside and outside the ring, as a neW 911 documentary shows. Neither man truly recovered, and nor 0 did their friendship. At 64, Frazier shows no signs of forgetting 8- A – but can he ever forgive? 00 8 WORDS ADAM HIGGINBOTHAM PORTRAIT STEFAN RUIZ C - XX COLD AND DARK,THE BIG BUILDING ON of the world, like that of Ali – born Cassius Clay .pdf North Broad Street in Philadelphia is closed now, the in Kentucky – began in the segregated heartland battered blue canvas ring inside empty and unused of the Deep South. Born in 1944, Frazier grew ; for the first time in more than 40 years. On the up on 10 acres of unyielding farmland in rural Pa outside, the boxing glove motifs and the black letters South Carolina, the 11th of 12 children raised in ge that spell out the words ‘Joe Frazier’s Gym’ in cast a six-room house with a tin roof and no running : concrete are partly covered by a ‘For Sale’ banner. water.As a boy, he played dice and cards and taught 1 ‘It’s shut down,’ Frazier tells me,‘and I’m going himself to box, dreaming of being the next Joe ; T to sell it.The highest bidder’s got it.’The gym is Louis. In 1961, at 17, he moved to Philadelphia. r where Frazier trained before becoming World Frazier was taken in by an aunt, and talked im Heavyweight Champion in 1970; later, it would also his way into a job at Cross Brothers, a kosher s be his home: for 23 years he lived alone, upstairs, in slaughterhouse.There, he worked on the killing i z a three-storey loft apartment. -

Sample Download

What they said about Thomas Myler’s previous books New York Fight Nights Thomas Myler has served up another collection of gripping boxing stories. The author packs such a punch with his masterful storytelling that you will feel you were ringside inhaling the sizzling atmosphere at each clash of the titans. A must for boxing fans. Ireland’s Own There are few more authoritative voices in boxing than Thomas Myler and this is another wonderfully evocative addition to his growing body of work. Irish Independent Another great book from the pen of the prolific Thomas Myler. RTE, Ireland’s national broadcaster The Mad and the Bad Another storytelling gem from Thomas Myler, pouring light into the shadows surrounding some of boxing’s most colourful characters. Irish Independent The best boxing book of the year from a top writer. Daily Mail Boxing’s Greatest Upsets: Fights That Shook The World A respected writer, Myler has compiled a worthy volume on the most sensational and talked-about upsets of the glove era, drawing on interviews, archive footage and worldwide contacts. Yorkshire Evening Post Fight fans will glory in this offbeat history of boxing’s biggest shocks, from Gentleman Jim’s knockout of John L. Sullivan in 1892 to the modern era. A must for your bookshelf. Hull Daily Mail Boxing’s Hall of Shame Boxing scribe Thomas Myler shares with the reader a ringside seat for the sport’s most controversial fights. It’s an engaging read, one that feeds our fascination with the darker side of the sport. Bert Sugar, US author and broadcaster Well written and thoroughly researched by one of the best boxing writers in these islands, Myler has a keen eye for the story behind the story. -

Addition to Summer Letter

May 2020 Dear Student, You are enrolled in Advanced Placement English Literature and Composition for the coming school year. Bowling Green High School has offered this course since 1983. I thought that I would tell you a little bit about the course and what will be expected of you. Please share this letter with your parents or guardians. A.P. Literature and Composition is a year-long class that is taught on a college freshman level. This means that we will read college level texts—often from college anthologies—and we will deal with other materials generally taught in college. You should be advised that some of these texts are sophisticated and contain mature themes and/or advanced levels of difficulty. In this class we will concentrate on refining reading, writing, and critical analysis skills, as well as personal reactions to literature. A.P. Literature is not a survey course or a history of literature course so instead of studying English and world literature chronologically, we will be studying a mix of classic and contemporary pieces of fiction from all eras and from diverse cultures. This gives us an opportunity to develop more than a superficial understanding of literary works and their ideas. Writing is at the heart of this A.P. course, so you will write often in journals, in both personal and researched essays, and in creative responses. You will need to revise your writing. I have found that even good students—like you—need to refine, mature, and improve their writing skills. You will have to work diligently at revising major essays. -

Waterloo in Myth and Memory: the Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick

Florida State University Libraries Electronic Theses, Treatises and Dissertations The Graduate School 2013 Waterloo in Myth and Memory: The Battles of Waterloo 1815-1915 Timothy Fitzpatrick Follow this and additional works at the FSU Digital Library. For more information, please contact [email protected] FLORIDA STATE UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES WATERLOO IN MYTH AND MEMORY: THE BATTLES OF WATERLOO 1815-1915 By TIMOTHY FITZPATRICK A Dissertation submitted to the Department of History in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Degree Awarded: Fall Semester, 2013 Timothy Fitzpatrick defended this dissertation on November 6, 2013. The members of the supervisory committee were: Rafe Blaufarb Professor Directing Dissertation Amiée Boutin University Representative James P. Jones Committee Member Michael Creswell Committee Member Jonathan Grant Committee Member The Graduate School has verified and approved the above-named committee members, and certifies that the dissertation has been approved in accordance with university requirements. ii For my Family iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to thank Drs. Rafe Blaufarb, Aimée Boutin, Michael Creswell, Jonathan Grant and James P. Jones for being on my committee. They have been wonderful mentors during my time at Florida State University. I would also like to thank Dr. Donald Howard for bringing me to FSU. Without Dr. Blaufarb’s and Dr. Horward’s help this project would not have been possible. Dr. Ben Wieder supported my research through various scholarships and grants. I would like to thank The Institute on Napoleon and French Revolution professors, students and alumni for our discussions, interaction and support of this project. -

Read a Pulitzer Prize-Winning Book

September 2020 Reading Challenge: Read a Pulitzer Prize-Winning Book Key for on which services the books are located: A = Axis 360 C = CloudLibrary H = Hoopla L = Libby O = Overdrive P = Print LP = Large Print eAudio = AudioCD = CD March by Geraldine Brooks (fiction) P, LP In a story inspired by the father character in "Little Women" and drawn from the journals and letters of Louisa May Alcott's father, a man leaves behind his family to serve in the Civil War and finds his beliefs challenged by his experiences. The Gulf: The Making of an American Sea by Jack E. Davis (non-fiction) P, C H A comprehensive history of the Gulf of Mexico and its identity as a region marked by hurricanes, oil fields, and debates about population growth and the environment demonstrates how its picturesque ecosystems have inspired and reflected key historical events. The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz (fiction) P, LT, O, L, O L Living with an old-world mother and rebellious sister, an urban New Jersey misfit dreams of becoming the next J. R. R. Tolkien and believes that a long-standing family curse is thwarting his efforts to find love and happiness. Late Wife by Claudia Emerson (poetry) P In Late Wife, a woman explores her disappearance from one life and reappearance in another as she addresses her former husband, herself, and her new husband in a series of epistolary poems. Though not satisfied in her first marriage, she laments vanishing from the life she and her husband shared for years. -

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction Honors a Distinguished Work of Fiction by an American Author, Preferably Dealing with American Life

Pulitzer Prize Winners Named after Hungarian newspaper publisher Joseph Pulitzer, the Pulitzer Prize for fiction honors a distinguished work of fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life. Chosen from a selection of 800 titles by five letter juries since 1918, the award has become one of the most prestigious awards in America for fiction. Holdings found in the library are featured in red. 2017 The Underground Railroad by Colson Whitehead 2016 The Sympathizer by Viet Thanh Nguyen 2015 All the Light we Cannot See by Anthony Doerr 2014 The Goldfinch by Donna Tartt 2013: The Orphan Master’s Son by Adam Johnson 2012: No prize (no majority vote reached) 2011: A visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 2010:Tinkers by Paul Harding 2009:Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 2008:The Brief and Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 2007:The Road by Cormac McCarthy 2006:March by Geraldine Brooks 2005 Gilead: A Novel, by Marilynne Robinson 2004 The Known World by Edward Jones 2003 Middlesex by Jeffrey Eugenides 2002 Empire Falls by Richard Russo 2001 The Amazing Adventures of Kavalier & Clay by Michael Chabon 2000 Interpreter of Maladies by Jhumpa Lahiri 1999 The Hours by Michael Cunningham 1998 American Pastoral by Philip Roth 1997 Martin Dressler: The Tale of an American Dreamer by Stephan Milhauser 1996 Independence Day by Richard Ford 1995 The Stone Diaries by Carol Shields 1994 The Shipping News by E. Anne Proulx 1993 A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain by Robert Olen Butler 1992 A Thousand Acres by Jane Smiley -

6 Diciembre 2015 Ingles.Cdr

THE DOORS TO LATIN AMERICA, arrival of the Spanish on the XVI Century. TIJUANA B.C. , HOST VENUE OF January 2016 will be an spectacular year, the second World Boxing Council female OUR NEXT FEMALE CONVENTION convention will be hosted on this magnificent place. “Here starts our homeland” that’s Tijuana´s motto, it is the first Latin America city that The greatest female fighters will travel to shares border with San Diega, US anf is the Tijuana with the main goal of spreading and fifth most populated city of Mexico having keep developing this sport as we are able to more than 1, 600,000 habitants on it. enjoy all of its cultural and historic attractions. Tijuana is a city of great commercial and cultural activity, its history began with the Editorial Index Future fights WBC Emerald Belt May-Pac Roman Gonzalez Golovkin Viktor Postol Jorge Linares Zulina Muñoz Mikaela Lauren Erica Farias Alicia Ashley Ibeth Zamora Yessica Chavez Soledad Matthysse Leo Santa Cruz becomes Diamond champion Francisco Vargas Directorio: Saul Alvarez “WBC Boxing World” is the official magazine of the World Boxing Council. Floyd´s final Hurrah . Executive Director WBC Cares Mauricio Sulaimán. WBC Annual Convention Subdirector Víctor Silva. Knowing a Champion: Deontay Wilder Marketing Manager José Antonio Arreola Sulaimán Muhammad Ali Honored Managing Editor Mauricio Sulaiman is presented with the keys to the Francisco Posada Toledo city of Miami Traducción PRESIDENT DANIEL ORTEGA: a great supporter of Paul Landeros / James Blears Nicaraguan boxing Design Director Alaín -

Waterloo 200

WATERLOO 200 THE OFFICIAL SOUVENIR PUBLICATION FOR THE BICENTENARY COMMEMORATIONS Edited by Robert McCall With an introduction by Major General Sir Evelyn Webb-Carter KCVO OBE DL £6.951 TheThe 200th Battle Anniversary of Issue Waterloo Date: 8th May 2015 The Battle of Waterloo The Isle of Man Post Offi ce is pleased 75p 75p Isle of Man Isle of Man to celebrate this most signifi cant historical landmark MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 in collaboration with 75p 75p Waterloo 200. Isle of Man Isle of Man MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 SET OF 8 STAMPS MINT 75p 75p Isle of Man Isle of Man TH31 – £6.60 PRESENTATION PACK TH41 – £7.35 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 FIRST DAY COVER 75p 75p Isle of Man Isle of Man TH91 – £7.30 SHEET SET MINT TH66 – £26.40 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 MM&C The Battle of Waterloo 2015 FOLDER “The whole art of war consists of guessing at what is on the other side of the hill” TH43 – £30.00 Field Marshal His Grace The Duke of Wellington View the full collection on our website: www. iomstamps.com Isle of Man Stamps & Coins GUARANTEE OF SATISFACTION - If you are not 100% PO Box 10M, IOM Post Offi ce satisfi ed with the product, you can return items for exchange Douglas, Isle of Man IM99 1PB or a complete refund up to 30 days from the date of invoice. -

The Longest Afternoon: the 400 Men Who Decided the Battle of Waterloo by Brendan Simms

2018-018 21 Feb. 2018 The Longest Afternoon: The 400 Men Who Decided the Battle of Waterloo by Brendan Simms . New York: Basic Books, 2015. Pp. xvii, 186. ISBN 978–0–465–06482–3. Review by Andrew J. Roscoe, US Navy ([email protected]). The general public often remembers the Battle of Waterloo as a monumental but remote and in- accessible conflict. Commanders like the Duke of Wellington, Napoleon Bonaparte, and Gebhard von Blücher dominate its narrative, not the average soldiers who did the fighting and dying in their thousands. In The Longest Afternoon , noted political scientist Brendan Simms 1 (Univ. of Cambridge) tells a masterful story of the 378 men of the 2nd Light Battalion, King’s German Le- gion, who defended the small Belgian farm of La Haye Sainte on the fateful afternoon of 18 June 1815 before running out of ammunition and giving way in the face of superior French numbers. The actions of the Hanoverian riflemen who occupied the center of the Allied army’s three advanced positions have been overshadowed by the defense of Hougoumont, the charge of the British heavy cavalry, the attacks of Ney’s French cavalry on the British infantry squares, and the defeat of the French Imperial Guard. Simms contends that the protracted, stalwart resistance of the Germans was decisive. Maintaining their position until late into the fight, they drew in and inflicted disproportionate losses on Napoleon’s troops. The author begins with the formation of the King’s German Legion—the Hanoverian exile force that fought loyally for George III during the Napoleonic Wars—but most of his book chroni- cles the contest in and around La Haye Sainte. -

Pulitzer Prize

1946: no award given 1945: A Bell for Adano by John Hersey 1944: Journey in the Dark by Martin Flavin 1943: Dragon's Teeth by Upton Sinclair Pulitzer 1942: In This Our Life by Ellen Glasgow 1941: no award given 1940: The Grapes of Wrath by John Steinbeck 1939: The Yearling by Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings Prize-Winning 1938: The Late George Apley by John Phillips Marquand 1937: Gone with the Wind by Margaret Mitchell 1936: Honey in the Horn by Harold L. Davis Fiction 1935: Now in November by Josephine Winslow Johnson 1934: Lamb in His Bosom by Caroline Miller 1933: The Store by Thomas Sigismund Stribling 1932: The Good Earth by Pearl S. Buck 1931 : Years of Grace by Margaret Ayer Barnes 1930: Laughing Boy by Oliver La Farge 1929: Scarlet Sister Mary by Julia Peterkin 1928: The Bridge of San Luis Rey by Thornton Wilder 1927: Early Autumn by Louis Bromfield 1926: Arrowsmith by Sinclair Lewis (declined prize) 1925: So Big! by Edna Ferber 1924: The Able McLaughlins by Margaret Wilson 1923: One of Ours by Willa Cather 1922: Alice Adams by Booth Tarkington 1921: The Age of Innocence by Edith Wharton 1920: no award given 1919: The Magnificent Ambersons by Booth Tarkington 1918: His Family by Ernest Poole Deer Park Public Library 44 Lake Avenue Deer Park, NY 11729 (631) 586-3000 2012: no award given 1980: The Executioner's Song by Norman Mailer 2011: Visit from the Goon Squad by Jennifer Egan 1979: The Stories of John Cheever by John Cheever 2010: Tinkers by Paul Harding 1978: Elbow Room by James Alan McPherson 2009: Olive Kitteridge by Elizabeth Strout 1977: No award given 2008: The Brief Wondrous Life of Oscar Wao by Junot Diaz 1976: Humboldt's Gift by Saul Bellow 2007: The Road by Cormac McCarthy 1975: The Killer Angels by Michael Shaara 2006: March by Geraldine Brooks 1974: No award given 2005: Gilead by Marilynne Robinson 1973: The Optimist's Daughter by Eudora Welty 2004: The Known World by Edward P. -

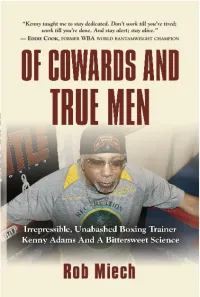

Of Cowards and True Men Order the Complete Book From

Kenny Adams survived on profanity and pugilism, turning Fort Hood into the premier military boxing outfit and coaching the controversial 1988 U.S. Olympic boxing team in South Korea. Twenty-six of his pros have won world-title belts. His amateur and professional successes are nonpareil. Here is the unapologetic and unflinching life of an American fable, and the crude, raw, and vulgar world in which he has flourished. Of Cowards and True Men Order the complete book from Booklocker.com http://www.booklocker.com/p/books/8941.html?s=pdf or from your favorite neighborhood or online bookstore. Enjoy your free excerpt below! Of Cowards and True Men Rob Miech Copyright © 2015 Rob Miech ISBN: 978-1-63490-907-5 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the author. Published by BookLocker.com, Inc., Bradenton, Florida, U.S.A. Printed on acid-free paper. BookLocker.com, Inc. 2015 First Edition I URINE SPRAYS ALL over the black canvas. A fully loaded Italian Galesi-Brescia 6.35 pearl-handled .25-caliber pistol tumbles onto the floor of the boxing ring. Just another day in the office for Kenny Adams. Enter the accomplished trainer’s domain and expect anything. “With Kenny, you never know,” says a longtime colleague who was there the day of Kenny’s twin chagrins. First off, there’s the favorite word. Four perfectly balanced syllables, the sweet matronly beginning hammered by the sour, vulgar punctuation.