A Historical and Legal Study of Sovereignty in the Canadian North : Terrestrial Sovereignty, 1870–1939

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Muskox Management Report Alaska Dept of Fish and Game Wildlife

Muskox Management Report of survey-inventory activities 1 July 1998–30 June 2000 Mary V. Hicks, Editor Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Wildlife Conservation December 2001 ADF&G Please note that population and harvest data in this report are estimates and may be refined at a later date. If this report is used in its entirety, please reference as: Alaska Department of Fish and Game. 2001. Muskox management report of survey-inventory activities 1 July 1998–30 June 2000. M.V. Hicks, editor. Juneau, Alaska. If used in part, the reference would include the author’s name, unit number, and page numbers. Authors’ names can be found at the end of each unit section. Funded in part through Federal Aid in Wildlife Restoration, Proj. 16, Grants W-27-2 and W-27-3. LOCATION 2 GAME MANAGEMENT UNIT: 18 (41,159 mi ) GEOGRAPHIC DESCRIPTION: Yukon–Kuskokwim Delta BACKGROUND NUNIVAK ISLAND Muskoxen were once widely distributed in northern and western Alaska but were extirpated by the middle or late 1800s. In 1929, with the support of the Alaska Territorial Legislature, the US Congress initiated a program to reintroduce muskoxen in Alaska. Thirty-one muskoxen were introduced from Greenland to Nunivak Island in Unit 18 during 1935–1936, as a first step toward reintroducing this species to Alaska. The Nunivak Island population grew slowly until approximately 1958 and then began a period of rapid growth. The first hunting season was opened in 1975, and the population has since fluctuated between 400 and 750 animals, exhibiting considerable reproductive potential, even under heavy harvest regimes. -

Horned Animals

Horned Animals In This Issue In this issue of Wild Wonders you will discover the differences between horns and antlers, learn about the different animals in Alaska who have horns, compare and contrast their adaptations, and discover how humans use horns to make useful and decorative items. Horns and antlers are available from local ADF&G offices or the ARLIS library for teachers to borrow. Learn more online at: alaska.gov/go/HVNC Contents Horns or Antlers! What’s the Difference? 2 Traditional Uses of Horns 3 Bison and Muskoxen 4-5 Dall’s Sheep and Mountain Goats 6-7 Test Your Knowledge 8 Alaska Department of Fish and Game, Division of Wildlife Conservation, 2018 Issue 8 1 Sometimes people use the terms horns and antlers in the wrong manner. They may say “moose horns” when they mean moose antlers! “What’s the difference?” they may ask. Let’s take a closer look and find out how antlers and horns are different from each other. After you read the information below, try to match the animals with the correct description. Horns Antlers • Made out of bone and covered with a • Made out of bone. keratin layer (the same material as our • Grow and fall off every year. fingernails and hair). • Are grown only by male members of the • Are permanent - they do not fall off every Cervid family (hoofed animals such as year like antlers do. deer), except for female caribou who also • Both male and female members in the grow antlers! Bovid family (cloven-hoofed animals such • Usually branched. -

Section E, Hoofed Animals

Hoofed Animals Hoofed Section E Caribou Muskox Section E-1 Section E-2 Moose Section E-3 Section E Diseases and Parasites of Hoofed Animals Nose and throat bots Hoofed Animals Hoofed Head Photo Credit: NWT Wildlife Division Caribou Section E-1.1 Lumpy jaw Contagious ecthyma Photo Credit: NWT Wildlife Division Caribou Section E-1.2 Photo Credit: GNWT Muskox Section E-2.1 Muskox Section E-2.2 Hoofed Animals Hoofed Section E Diseases and Parasites of Hoofed Animals Besnoitiosis Wildlife Division NWT Photo credit: Head Photo Credit: Susan Kutz Caribou Section E-1.11 Muskox Section E-2.6 Ticks Skin Moose Section E-3.1 Section E Diseases and Parasites of Hoofed Animals Warts Hoofed Animals Hoofed Skin Photo Credit: D. Campbell Caribou Section E-1.3 Moose Section E-3.2 Warbles Contagious ecthyma Photo credit: Dr. G. Wobeser Photo credit: Dr. Photo Credit: GNWT Caribou Section E-1.4 Muskox Section E-2.2 Hoofed Animals Hoofed Section E Diseases and Parasites of Hoofed Animals Besnoitiosis Wildlife Division NWT Photo credit: Photo Credit: Susan Kutz Caribou Section E-1.11 Muskox Section E-2.6 Skin Brucellosis Photo credit: Dr. G. Wobeser G. Photo credit: Dr. Caribou Section E-1.10 Muskox Section E-2.5 Moose Section E-3.6 Section E Diseases and Parasites of Hoofed Animals Liver tapeworm cyst Hoofed Animals Hoofed Photo credit: Dr. G. Wobeser Photo credit: Dr. Caribou Section E-1.5 Organs Moose Section E-3.3 Tapeworm cysts in the Lungs (Hydatid disease) Brucellosis Photo credit: Dr. -

Alaska Muskox Herd Continues to Increase

SERVICE FISH ANDWILDLIFE SERVICE For Release to PM's AUGUST14, 195b ALASKANMUSKOX HERD CONTIBUES TO INCREASE Wild muskox on the Nunivak Island National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska are show- ing a continuing increase in their numbers, according to the Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior reports. This yearts aerial survey, made from June 22 to July 4, indicates that the herd now contains between 94 and 100 animals, The 1953 total was 90. he herd was observed to contain 25 adult bulls and 21 calves. The bodies of four dead animals, all bulls, were recovered. Thousands of muskox once occupied the arctic region between the tree line to the south and the permanent icecap to the north, and their meat and robes became an important item of commerce in the far north. By the end of the 19th centruy, whale hunters had exterminated the oxen from much of its former range. The last muskox in Alaska was killed prior to 1865. Refuges were established in Canada to safeguard that country's residual herds and to foster repopulation of former ranges. In 192'7 resident Alaskans appealed to Congress for funds to purchase a small herd of muskox. Three years later, when the funds were approved, the former Bureau of Biological Survey was assigned the job of attempting to reestablish the herd-in Alaska. After a two-month trip from Green- land of approximately 14,000 miles, 31 animals were released in a 4,000-acre enclo- sure at the College Experimental Farm near Fairbanks, Alaska. During the next four years feeding experiments and studies were carried on to see if domestic herds of these animals could be developed, Because the muskox proved both difficult and dangerous to handle, the entire herd was moved in 1935 and 1936 to tho million-acre Nunivak refuge whore amp10 range of good quality was available, Although the size of the herd has moro than tripled sines 1930, the breeding potential of the animal is low. -

Reindeer Grazing Permits on the Seward Peninsula

U.S. Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management Anchorage Field Office 4700 BLM Road Anchorage, Alaska 99507 http://www.blm.gov/ak/st/en/fo/ado.html Environmental Assessment: DOI-BLM-AK-010-2009-0007-EA Reindeer Grazing Permits on the Seward Peninsula Applicant: Clark Davis Case File No.: F-035186 Applicant: Fred Goodhope Case File No.: F-030183 Applicant: Thomas Gray Case File No.: FF-024210 Applicant: Nathan Hadley Case File No.: FF-085605 Applicant: Merlin Henry Case File No.: F-030387 Applicant: Harry Karmun Case File No. : F-030432 Applicant: Julia Lee Case File No.: F-030165 Applicant: Roger Menadelook Case File No.: FF-085288 Applicant: James Noyakuk Case File No.: FF-019442 Applicant: Leonard Olanna Case File No.: FF-011729 Applicant: Faye Ongtowasruk Case File No.: FF-000898 Applicant: Palmer Sagoonick Case File No.: FF-000839 Applicant: Douglas Sheldon Case File No.: FF-085604 Applicant: John A. Walker Case File No.: FF-087313 Applicant: Clifford Weyiouanna Case File No.: FF-011516 Location: Bureau of Land Management lands on the Seward Peninsula Prepared By: BLM, Anchorage Field Office, Resources Branch December 2008 DECISION RECORD and FINDING OF NO SIGNIFICANT IMPACT I. Decision: It is my decision to issue ten-year grazing permits on Bureau of Land Management lands to reindeer herders on the Seward and Baldwin peninsulas, Alaska. The permits shall be subject to the terms and conditions set forth in Alternative B of the attached Reindeer Grazing Programmatic Environmental Assessment. II. Rationale for the Decision: The Reindeer Industry Act of 1937, 500 Stat. 900, authorizes the Secretary’s regulation of reindeer grazing on Federal public lands on the peninsulas. -

The Occurrence of Cereal Cultivation in China

The Occurrence of Cereal Cultivation in China TRACEY L-D LU NEARL Y EIGHTY YEARS HAVE ELAPSED since Swedish scholar J. G. Andersson discovered a piece of rice husk on a Yangshao potsherd found in the middle Yel low River Valley in 1927 (Andersson 1929). Today, many scholars agree that China 1 is one of the centers for an indigenous origin of agriculture, with broom corn and foxtail millets and rice being the major domesticated crops (e.g., Craw-· ford 2005; Diamond and Bellwood 2003; Higham 1995; Smith 1995) and dog and pig as the primary animal domesticates (Yuan 2001). It is not clear whether chicken and water buffalo were also indigenously domesticated in China (Liu 2004; Yuan 2001). The origin of agriculture in China by no later than 9000 years ago is an impor tant issue in prehistoric archaeology. Agriculture is the foundation of Chinese civ ilization. Further, the expansion of agriculture in Asia might have related to the origin and dispersal of the Austronesian and Austroasiatic speakers (e.g., Bellwood 2005; Diamond and Bellwood 2003; Glover and Higham 1995; Tsang 2005). Thus the issue is essential for our understanding of Asian and Pacific prehistory and the origins of agriculture in the world. Many scholars have discussed various aspects regarding the origin of agriculture in China, particularly after the 1960s (e.g., Bellwood 1996, 2005; Bellwood and Renfrew 2003; Chen 1991; Chinese Academy of Agronomy 1986; Crawford 1992, 2005; Crawford and Shen 1998; Flannery 1973; Higham 1995; Higham and Lu 1998; Ho 1969; Li and Lu 1981; Lu 1998, 1999, 2001, 2002; MacN eish et al. -

02/02/2018 1 Marco Apollonio and Roberta Chirichella

02/02/2018 Marco Apollonio and Roberta Chirichella Department of Veterinary Medicine University of Sassari, Italy First Annual General Meeting of ENETWILD Parma 16-18 January 2018 1 02/02/2018 2005 - 2015 DATA FROM EUROPEAN COUNTRIES: Walter Arnold and Friedrich Reimoser (Austria); Jim Casaer (Belgium); Luděk Bartoš(Czeck R.); Krešimir Krapinec (Croatia); Reidar Andersen (Denmark); Tiit Randveer (Estonia); Vesa Ruusila (Finland); Christine Saint-Andrieux (France); Marco Heurich (Germany); Haritakis Papaioannou (Greece); Csányi Sándor (Hungary); Rory Putman and Peter Watson (Ireland and UK); Francesco Riga (Italy); Jānis Ozoliņš (Latvia); Linas Balčiauskas (Lituania); Dime Melovski (Macedonia); Geert W. T. A. Groot Bruinderink (Netherlands); Atle Mysterud (Norway); Tomasz Borowik (Poland); Carlos Fonseca (Portugal); Istvan Szabo (Romania); Milan Paunović (Serbia); Slavomír Find'o (Slovakia); Boštján Pokorny (Slovenia); Juan Carranza (Spain); Göran Ericsson (Sweden); Reinhard Schnidrig-Petrig (Swizerland). Wild boar distribution in Europe and Near East 2 02/02/2018 WILD BOAR EXTICTION IN EUROPE • SWITZERLAND • BALTIC COUNTRIES • SWEDEN • NORWAY • DENMARK • NETHERLANDS • GREAT BRITAIN • SLOVENIA (ALMOST) Italy (Ghigi A., 1917, 1950) 3 02/02/2018 Italy (Apollonio. et al., 1988) Reintroduction restocking Natural immigration Reintroduction Restocking Natural immigration Autoctonous restocking Restocking Autoctonous Restocking Autoctonous Sus scrofa meridionalis Restocking (with Sus scrofa of Reintroduction different regions) Italy (Apollonio -

Advanced Training Techniques for Oxen Techguide

Tillers‟ TechGuide Advanced Training Techniques for Oxen by Drew Conroy Assistant Professor, University of New Hampshire Copyright, 1995: Tillers International Chapter 1 Introduction Acknowledgements A team of well-trained oxen is a joy to watch and The author was inspired to write this TechGuide while to work. Even the most skilled cattlemen are teaching an “Oxen Basics” workshop at Tillers. Drew impressed with the responsiveness and spent evenings reviewing literature that Tillers has obedience that oxen demonstrate.under what I gathered from around the world on ox training. He was would consider ideal circumstances. I had no impressed that, despite minimal interaction and brief documentation, the training approaches from around the knowledge of training cattle, no written materials world were very similar. He decided to expand on training to fall back on, and only a basic understanding of techniques beyond what he had included in the Oxen cattle behavior. As a boy, I did have lots of time, Handbook and beyond our prior TechGuide on Training patience, and some guidance from experienced Young Steers. ox teamsters. We look forward to comments. Future revisions will Many years and many teams later, I can honestly integrate suggestions, corrections, and improvements to say those first oxen were also my best-trained illustrations. Please send comments to: Tillers th team. My success with that team was due International , 5239 South 24 Street, Kalamazoo, MI primarily to the cattle being very friendly, hand 49002 USA. fed since birth, and very young when I began Publishing of this revision was supported by the Roy and training. -

Spatial Scales of Muskox Resource Selection in Late Winter

SPATIAL SCALES OF MUSKOX RESOURCE SELECTION IN LATE WINTER A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of the University of Alaska Fairbanks in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE By Kenneth J. Wilson, B.A. Fairbanks, Alaska May 1992 SPATIAL SCALES OF MUSKOX RESOURCE SELECTION IN LATE WINTER By Kenneth J. Wilson RECOMMENDED: Advisory Committee Chair Department Head APPROVED: Dean, Coll£ge-e£>Naturai Sciences Dean orthe Graduate School Date ABSTRACT I examined resource selection by muskoxen in late winter on the coastal plain of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, Alaska, by comparing use and availability at regional, meso, local, and micro spatial scales. Use of vegetation types for feeding appears to be based on selection of areas of shallow soft snow with high cover of sedges, dead vegetation, and total vegetation, and on selection against areas of little vegetation cover or deep hardpacked snow. Muskoxen used moist sedge, tussock sedge, and Dryas terrace tundra in proportion to availability and avoided barren ground, partially vegetated, riparian shrub, and Dryas ridge tundra. Selection for areas of shallow snow occurred within vegetation types as well as between vegetation types. Occurrence of sedges and grasses in the diet was greater than availability. Feeding zones were primarily on windblown vegetated bluffs; these areas are distributed in narrow bands along creeks, rivers, and the coastline. i i i TABLE OF CONTENTS ABSTRACT................................................................................................................................iii -

A Field Guide to Common Wildlife Diseases and Parasites in the Northwest Territories

A Field Guide to Common Wildlife Diseases and Parasites in the Northwest Territories 6TH EDITION (MARCH 2017) Introduction Although most wild animals in the NWT are healthy, diseases and parasites can occur in any wildlife population. Some of these diseases can infect people or domestic animals. It is important to regularly monitor and assess diseases in wildlife populations so we can take steps to reduce their impact on healthy animals and people. • recognize sickness in an animal before they shoot; •The identify information a disease in this or field parasite guide in should an animal help theyhunters have to: killed; • know how to protect themselves from infection; and • help wildlife agencies monitor wildlife disease and parasites. The diseases in this booklet are grouped according to where they are most often seen in the body of the Generalanimal: skin, precautions: head, liver, lungs, muscle, and general. Hunters should look for signs of sickness in animals • poor condition (weak, sluggish, thin or lame); •before swellings they shoot, or lumps, such hair as: loss, blood or discharges from the nose or mouth; or • abnormal behaviour (loss of fear of people, aggressiveness). If you shoot a sick animal: • Do not cut into diseased parts. • Wash your hands, knives and clothes in hot, soapy animal, and disinfect with a weak bleach solution. water after you finish cutting up and skinning the 2 • If meat from an infected animal can be eaten, cook meat thoroughly until it is no longer pink and juice from the meat is clear. • Do not feed parts of infected animals to dogs. -

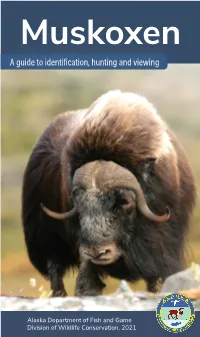

Muskoxen a Guide to Identification, Hunting and Viewing

Muskoxen A guide to identification, hunting and viewing Alaska Department of Fish and Game Division of Wildlife Conservation, 2021 Muskoxen A guide to identification, hunting and viewing A Note to Readers The information in this booklet will assist in identifying muskoxen, preparing for a muskox hunting trip, and provide interesting information about muskoxen in Alaska. Details in the Muskox Information section are adapted from the Alaska Wildlife Notebook Series prepared by Tim Smith and revised by John Coady and Randy Kacyon. Alaska Wildlife Notebook Series, © 2008. Many photos in this booklet are provided to aid in understanding of muskoxen and their habitat. Not all images are referenced within the text. Photos that indicate seasons illustrate the significant changes that occur to muskox appearance over the course of the year. Additional information on muskoxen can be found at the Alaska Department of Fish and Game (ADF&G) website: www.adfg.alaska.gov Table of Contents Muskox Information Distribution & Physical Attributes . 2 Life History . 4 History in Alaska . 8 Muskoxen and Humans . 10 Identification Identification of Groups . 12 Identification by Age and Sex . 14 Identification Quiz . 20 Hunting Hunter Requirements . 26 Reporting, Trophy Destruction, Labeling . 27 Hunt Information . 28 Planning Your Hunt . 30 Meat Care . 32 Preventing Wounding Loss . 34 From Field to Table . 36 Meat Salvage . 37 Living with Muskox Sharing the Country with Muskoxen . 38 Muskox Information Distribution Muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) are northern animals well adapted to life in the Arctic. At the end of the last ice age, muskoxen were found across northern Europe, Asia, Greenland and North America, including Alaska. -

The Water Buffalo: Domestic Anima of the Future

The Water Buffalo: Domestic Anima © CopyrightAmerican Association o fBovine Practitioners; open access distribution. of the Future W. Ross Cockrill, D.V.M., F.R.C.V.S., Consultant, Animal Production, Protection & Health, Food and Agriculture Organization Rome, Italy Summary to produce the cattalo, or beefalo, a heavy meat- The water buffalo (Bubalus bubalis) is a type animal for which widely publicized claims neglected bovine animal with a notable and so far have been made. The water buffalo has never been unexploited potential, especially for meat and shown to produce offspring either fertile or sterile milk production. World buffalo stocks, which at when mated with cattle, although under suitable present total 150 million in some 40 countries, are conditions a bull will serve female buffaloes, while increasing steadily. a male buffalo will mount cows. It is important that national stocks should be There are about 150 million water buffaloes in the upgraded by selective breeding allied to improved world compared to a cattle population of around 1,- management and nutrition but, from the stand 165 million. This is a significant figure, especially point of increased production and the full realiza when it is considered that the majority of buffaloes tion of potential, it is equally important that are productive in terms of milk, work and meat, or crossbreeding should be carried out extensively any two of these outputs, whereas a high proportion of especially in association with schemes to increase the world’s cattle is economically useless. and improve buffalo meat production. In the majority of buffalo-owning countries, and in Meat from buffaloes which are reared and fed all those in which buffaloes make an important con for early slaughter is of excellent quality.