Choje Akong Tulku Rinpoche

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JACEK TRZEBUNIAK* Analysis of Development of the Tibetan Tulku

The Polish Journal of the Arts and Culture Nr 10 (2/2014) / ARTICLE JACEK TRZEBUNIAK* (Uniwersytet Jagielloński) Analysis of Development of the Tibetan Tulku System in Western Culture ABSTRACT With the development of Tibetan Buddhism in Europe and America, from the second half of the twentieth century, the phenomenon of recognising a person as a reincarnation of Bud- dhist teachers appeared in this part of the world. Tibetan masters expected that the identified person will serve important social and religious functions for Buddhist communities. How- ever, after several decades since the first recognitions, the Western tulkus do not play the same important role in the development of Buddhism, as tulkus in China, and the Tibetan communities in exile. The article analyses the cultural and social causes of the different functioning of tulku institution in Western societies. The article shows that a different un- derstanding of identity, power and hierarchy mean that tulkus do not play significant roles in the development of Buddhism in this part of the world. KEY WORDS religious studies, Tibetan Buddhism, tulku, West INTRODUCTION Tulku (Tib. sprul sku) is a person in Tibetan Buddhism tradition who is recog- nised as a reincarnation of a famous Buddhist master. The tradition originated in the 13th century in the Kagyu (Tib. bka’ brgyud) sect when students of the Dusum Khyenpa (Tib. dus gsum mkhyen pa), after his death, found a boy and * Wydział Filozoficzny, Katedra Porównawczych Studiów Cywilizacji Uniwersytet Jagielloński w Krakowie, Polska e-mail: [email protected] 116 Jacek Trzebuniak recognised him as a reincarnation of their master1. -

Chenrezig Practice

1 Chenrezig Practice Collected Notes Bodhi Path Natural Bridge, VA February 2013 These notes are meant for private use only. They cannot be reproduced, distributed or posted on electronic support without prior explicit authorization. Version 1.00 ©Tsony 2013/02 2 About Chenrezig © Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoche in Heart Treasure of the Enlightened One. ISBN-10: 0877734933 ISBN-13: 978-0877734932 In the Tibetan Buddhist pantheon of enlightened beings, Chenrezig is renowned as the embodiment of the compassion of all the Buddhas, the Bodhisattva of Compassion. Avalokiteshvara is the earthly manifestation of the self born, eternal Buddha, Amitabha. He guards this world in the interval between the historical Sakyamuni Buddha, and the next Buddha of the Future Maitreya. Chenrezig made a a vow that he would not rest until he had liberated all the beings in all the realms of suffering. After working diligently at this task for a very long time, he looked out and realized the immense number of miserable beings yet to be saved. Seeing this, he became despondent and his head split into thousands of pieces. Amitabha Buddha put the pieces back together as a body with very many arms and many heads, so that Chenrezig could work with myriad beings all at the same time. Sometimes Chenrezig is visualized with eleven heads, and a thousand arms fanned out around him. Chenrezig may be the most popular of all Buddhist deities, except for Buddha himself -- he is beloved throughout the Buddhist world. He is known by different names in different lands: as Avalokiteshvara in the ancient Sanskrit language of India, as Kuan-yin in China, as Kannon in Japan. -

The Lhasa Jokhang – Is the World's Oldest Timber Frame Building in Tibet? André Alexander*

The Lhasa Jokhang – is the world's oldest timber frame building in Tibet? * André Alexander Abstract In questo articolo sono presentati i risultati di un’indagine condotta sul più antico tempio buddista del Tibet, il Lhasa Jokhang, fondato nel 639 (circa). L’edificio, nonostante l’iscrizione nella World Heritage List dell’UNESCO, ha subito diversi abusi a causa dei rifacimenti urbanistici degli ultimi anni. The Buddhist temple known to the Tibetans today as Lhasa Tsuklakhang, to the Chinese as Dajiao-si and to the English-speaking world as the Lhasa Jokhang, represents a key element in Tibetan history. Its foundation falls in the dynamic period of the first half of the seventh century AD that saw the consolidation of the Tibetan empire and the earliest documented formation of Tibetan culture and society, as expressed through the introduction of Buddhism, the creation of written script based on Indian scripts and the establishment of a law code. In the Tibetan cultural and religious tradition, the Jokhang temple's importance has been continuously celebrated soon after its foundation. The temple also gave name and raison d'etre to the city of Lhasa (“place of the Gods") The paper attempts to show that the seventh century core of the Lhasa Jokhang has survived virtually unaltered for 13 centuries. Furthermore, this core building assumes highly significant importance for the fact that it represents authentic pan-Indian temple construction technologies that have survived in Indian cultural regions only as archaeological remains or rock-carved copies. 1. Introduction – context of the archaeological research The research presented in this paper has been made possible under a cooperation between the Lhasa City Cultural Relics Bureau and the German NGO, Tibet Heritage Fund (THF). -

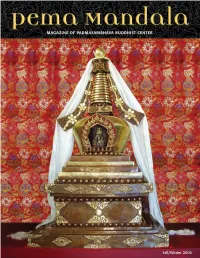

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1

5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:02 PM Page 1 Fall/Winter 2006 5 Pema Mandala Fall 06 11/21/06 12:03 PM Page 2 Volume 5, Fall/Winter 2006 features A Publication of 3 Letter from the Venerable Khenpos Padmasambhava Buddhist Center Nyingma Lineage of Tibetan Buddhism 4 New Home for Ancient Treasures A long-awaited reliquary stupa is now at home at Founding Directors Ven. Khenchen Palden Sherab Rinpoche Padma Samye Ling, with precious relics inside. Ven. Khenpo Tsewang Dongyal Rinpoche 8 Starting to Practice Dream Yoga Rita Frizzell, Editor/Art Director Ani Lorraine, Contributing Editor More than merely resting, we can use the time we Beth Gongde, Copy Editor spend sleeping to truly benefit ourselves and others. Ann Helm, Teachings Editor Michael Nott, Advertising Director 13 Found in Translation Debra Jean Lambert, Administrative Assistant A student relates how she first met the Khenpos and Pema Mandala Office her experience translating Khenchen’s teachings on For subscriptions, change of address or Mipham Rinpoche. editorial submissions, please contact: Pema Mandala Magazine 1716A Linden Avenue 15 Ten Aspirations of a Bodhisattva Nashville, TN 37212 Translated for the 2006 Dzogchen Intensive. (615) 463-2374 • [email protected] 16 PBC Schedule for Fall 2006 / Winter 2007 Pema Mandala welcomes all contributions submitted for consideration. All accepted submissions will be edited appropriately 18 Namo Buddhaya, Namo Dharmaya, for publication in a magazine represent- Nama Sanghaya ing the Padmasambhava Buddhist Center. Please send submissions to the above A student reflects on a photograph and finds that it address. The deadline for the next issue is evokes more symbols than meet the eye. -

The People's Curator

8 ISSUES AND INSIGHTS MUMBAI | 15 JUNE 2019 > proving oneself innocent was on the accused. gle biggest fear, patently unfounded, was a Fourteen and 15-year olds were sent to jail military coup. The existing army department Rajnath Singh’s dilemma on charges of copying. The pass percentage was turned first into the department of Lessons from HK in the UP High School Board examination defence and later the MoD. At the time, The new defence minister has to correct a major for Class X in 1991 was 58.03. In 1992, after defence secretary H M Patel and his successor t has been a fairly the anti-copying law was put in place, it twice offered to integrate the service head- crowded fortnight asymmetry. Will his discipline come in the way? slipped to 14.7. Singh had to pay for his con- quarters with MoD. But General Rajindersinhji I in terms of news, victions: He contested the Assembly election and General K S Thimayya refused, fearing and so some might channels chattered on loudly about how from Mohana, a student-dominated they would lose operational command and have missed what, Rajnath Singh ka kad gir gaya hai (Rajnath constituency near Lucknow in 1993, and was the panoply of pomp and pageantry by joining for me, has been the Singh has lost his stature). By the evening, defeated comprehensively. He was sent to the ministerial whirlpool. most interesting and the government had reversed the decision the Rajya Sabha in 1994. He became a Soon, the army got fully involved in J&K, perhaps important and reissued the notification. -

Escape to Lhasa Strategic Partner

4 Nights Incentive Programme Escape to Lhasa Strategic Partner Country Name Lhasa, the heart and soul of Tibet, is a city of wonders. The visits to different sites in Lhasa would be an overwhelming experience. Potala Palace has been the focus of the travelers for centuries. It is the cardinal landmark and a structure of massive proportion. Similarly, Norbulingka is the summer palace of His Holiness Dalai Lama. Drepung Monastery is one of the world’s largest and most intact monasteries, Jokhang temple the heart of Tibet and Barkhor Market is the place to get the necessary resources for locals as well as souvenirs for tourists. At the end of this trip we visit the Samye Monastery, a place without which no journey to Tibet is complete. StrategicCountryPartner Name Day 1 Arrive in Lhasa Country Name Day 1 o Morning After a warm welcome at Gonggar Airport (3570m) in Lhasa, transfer to the hotel. Distance (Airport to Lhasa): 62kms/ 32 miles Drive Time: 1 hour approx. Altitude: 3,490 m/ 11,450 ft. o Leisure for acclimatization Lhasa is a city of wonders that contains many culturally significant Tibetan Buddhist religious sites and lies in a valley next to the Lhasa River. StrategicCountryPartner Name Day 2 In Lhasa Country Name Day 2 o Morning: Set out to visit Sera and Drepung Monasteries Founded in 1419, Sera Monastery is one of the “great three” Gelukpa university monasteries in Tibet. 5km north of Lhasa, the Sera Monastery’s setting is one of the prettiest in Lhasa. The Drepung Monastery houses many cultural relics, making it more beautiful and giving it more historical significance. -

Karmapa Karma Pakshi (1206-1283)

CUỘC ĐỜI SIÊU VIỆT CỦA 16 VỊ TỔ KARMAPA TÂY TẠNG Biên soạn: Karma Thinley Rinpoche Nguyên tác: The History of Sixteen Karmapas of Tibet Karmapa Rangjung Rigpe Dorje XVI Karma Thinley Rinpoche - Việt dịch: Nguyễn An Cư Thiện Tri Thức 2543-1999 THIỆN TRI THỨC MỤC LỤC LỜI NÓI ĐẦU ............................................................................................ 7 LỜI TỰA ..................................................................................................... 9 DẪN NHẬP .............................................................................................. 12 NỀN TẢNG LỊCH SỬ VÀ LÝ THUYẾT ................................................ 39 Chương I: KARMAPA DUSUM KHYENPA (1110-1193) ...................... 64 Chương II: KARMAPA KARMA PAKSHI (1206-1283) ......................... 70 Chương III: KARMAPA RANGJUNG DORJE (1284-1339) .................. 78 Chương IV: KARMAPA ROLPE DORJE (1340-1383) ........................... 84 Chương V: KARMAPA DEZHIN SHEGPA (1384-1415) ........................ 95 Chương VI: KARMAPA THONGWA DONDEN (1416-1453) ............. 102 Chương VII: KARMAPA CHODRAG GYALTSHO (1454-1506) ........ 106 Chương VIII: KARMAPA MIKYO DORJE (1507-1554) ..................... 112 Chương IX: KARMAPA WANGCHUK DORJE (1555-1603) .............. 122 Chương X: KARMAPA CHOYING DORJE (1604-1674) .................... 129 Chương XI: KARMAPA YESHE DORJE (1676-1702) ......................... 135 Chương XII: KARMAPA CHANGCHUB DORJE (1703-1732) ........... 138 Chương XIII: KARMAPA DUDUL DORJE (1733-1797) .................... -

Recounting the Fifth Dalai Lama's Rebirth Lineage

Recounting the Fifth Dalai Lama’s Rebirth Lineage Nancy G. Lin1 (Vanderbilt University) Faced with something immensely large or unknown, of which we still do not know enough or of which we shall never know, the author proposes a list as a specimen, example, or indication, leaving the reader to imagine the rest. —Umberto Eco, The Infinity of Lists2 ncarnation lineages naming the past lives of eminent lamas have circulated since the twelfth century, that is, roughly I around the same time that the practice of identifying reincarnating Tibetan lamas, or tulkus (sprul sku), began.3 From the twelfth through eighteenth centuries it appears that incarnation or rebirth lineages (sku phreng, ’khrungs rabs, etc.) of eminent lamas rarely exceeded twenty members as presented in such sources as their auto/biographies, supplication prayers, and portraits; Dölpopa Sherab Gyeltsen (Dol po pa Shes rab rgyal mtshan, 1292–1361), one such exception, had thirty-two. Among other eminent lamas who traced their previous lives to the distant Indic past, the lineages of Nyangrel Nyima Özer (Nyang ral Nyi ma ’od zer, 1124–1192) had up 1 I thank the organizers and participants of the USF Symposium on The Tulku Institution in Tibetan Buddhism, where this paper originated, along with those of the Harvard Buddhist Studies Forum—especially José Cabezón, Jake Dalton, Michael Sheehy, and Nicole Willock for the feedback and resources they shared. I am further indebted to Tony K. Stewart, Anand Taneja, Bryan Lowe, Dianna Bell, and Rae Erin Dachille for comments on drafted materials. I thank the Chiang Ching-kuo Foundation for International Scholarly Exchange for their generous support during the final stages of revision. -

The First National Conference Government in Jammu and Kashmir, 1948-53

THE FIRST NATIONAL CONFERENCE GOVERNMENT IN JAMMU AND KASHMIR, 1948-53 THESIS SUBMITTED FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF Doctor of Philosophy IN HISTORY BY SAFEER AHMAD BHAT Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University UNDER THE SUPERVISION OF PROF. ISHRAT ALAM CENTRE OF ADVANCED STUDY DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 2019 CANDIDATE’S DECLARATION I, Safeer Ahmad Bhat, Centre of Advanced Study, Department of History, certify that the work embodied in this Ph.D. thesis is my own bonafide work carried out by me under the supervision of Prof. Ishrat Alam at Aligarh Muslim University, Aligarh. The matter embodied in this Ph.D. thesis has not been submitted for the award of any other degree. I declare that I have faithfully acknowledged, given credit to and referred to the researchers wherever their works have been cited in the text and the body of the thesis. I further certify that I have not willfully lifted up some other’s work, para, text, data, result, etc. reported in the journals, books, magazines, reports, dissertations, theses, etc., or available at web-sites and included them in this Ph.D. thesis and cited as my own work. The manuscript has been subjected to plagiarism check by Urkund software. Date: ………………… (Signature of the candidate) (Name of the candidate) Certificate from the Supervisor Maulana Azad Library, Aligarh Muslim University This is to certify that the above statement made by the candidate is correct to the best of my knowledge. Prof. Ishrat Alam Professor, CAS, Department of History, AMU (Signature of the Chairman of the Department with seal) COURSE/COMPREHENSIVE EXAMINATION/PRE- SUBMISSION SEMINAR COMPLETION CERTIFICATE This is to certify that Mr. -

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts

The Tulku System in Tibetan Buddhism: Its Reliability, Orthodoxy and Social Impacts By Ramin Etesami A thesis submitted to the graduate school in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts at the International Buddhist College, Thailand March, 20 Abstract The Tulku institution is a unique characteristic of Tibetan Buddhism with a central role in this tradition, to the extent that it is present in almost every aspect of Tibet’s culture and tradition. However, despite this central role and the scope and diversity of the socio-religious aspects of the institution, only a few studies have so far been conducted to shed light on it. On the other hand, an aura of sacredness; distorted pictures projected by the media and film industries;political propaganda and misinformation; and tendencies to follow a pattern of cult behavior; have made the Tulku institution a highly controversial topic for research; and consequently, an objective study of the institution based on a critical approach is difficult. The current research is an attempt to comprehensively examine different dimensions of the Tulku tradition with an emphasis on the issue of its orthodoxy with respect to the core doctrines of Buddhism and the social implications of the practice. In this research, extreme caution has been practiced to firstly, avoid any kind of bias rooted in faith and belief; and secondly, to follow a scientific methodology in reviewing evidence and scriptures related to the research topic. Through a comprehensive study of historical accounts, core Buddhist texts and hagiographic literature, this study has found that while the basic Buddhist doctrines allow the possibility for a Buddhist teacher or an advanced practitioner to “return back to accomplish his tasks, the lack of any historical precedence which can be viewed as a typical example of the practice in early Buddhism makes the issue of its orthodoxy equivocal and relative. -

YEAR 6/2019 KAGYU SAMYE LING: Meditation

YEAR 6/2019 KAGYU SAMYE LING: meditation & yoga retreat – with cat & phil Eskdalemuir, Dumfriesshire, Scotland Kagyu Samye Ling - tibetan buddhist centre/kagyu tradition Thursday, 8th – Sunday, 11th August 2019 Cost: £350 tuition (includes donation to Kagyu Samye Ling) This is an additional way we have chosen to support the monastery & their ongoing charitable work. Accommodation to be booked directly with Samye Ling. Deposit: £200 to hold a space – (FULL CAPACITY – PREVIOUS YEARS) Balance due: 8th June (two months prior) – NO REFUNDS AFTER THIS DATE Payment methods: cash/cheque/bank transfer Cheques made out to: Catherine Alip-Douglas Bank transfer to: TSB – Bayswater Branch, 30-32 Westbourne Grove sort code: 309059, account number:14231860, Swift/BIC code: IBAN:GB49TSBS30905914231860 BIC: TSBSGB2AXXX The Retreat: 3 nights/4 days includes a tour of samye ling, daily yoga sessions (2- 2.5hours), lectures, meditation practice with Samye Ling’s sangha, a film screening of “AKONG” based on Akong Rinpoche, one of the founders of KSL and informal gatherings in an environment conducive to a proper ‘retreat’. As always, this retreat is also part of the Sangyé Yoga School's 2019 TT. There will be time for walks in the beautiful surroundings and reading books from their well-stocked and newly expanded gift shop. NOT INCLUDED: accommodation (many options depending on your budget) & travel. Kagyu Samye Ling provides the perfect environment to reconnect with nature, go deeper in your meditation practice, learn about the foundations of Tibetan Buddhism and the Kagyu lineage. It is a simple retreat for students who want to get to the heart of a practice and spend more time than usual in meditation sessions. -

HYDERABAD CAMPUS LIBRARY Weekly New-Book Display - 32 (01 – 07 March, 2021) Acc

BITS PILANI – HYDERABAD CAMPUS LIBRARY Weekly New-Book Display - 32 (01 – 07 March, 2021) Acc. No : 41113 Call No : 005.133 SEV-C Python for Everybody is designed to introduce students to programming and software development through the lens of exploring data. You can think of the Python programming language as your tool to solve data problems that are beyond the capability of a spreadsheet. Python is an easy to use and easy to learn programming language that is freely available on Macintosh, Windows, or Linux computers. So once you learn Python you can use it for the rest of your career without needing to purchase any software. There are free downloadable electronic copies of this book in various formats and supporting materials for the book at www.pythonlearn.com. The course materials are available to you under a Creative Commons License so you can adapt them to teach your own… BITS Pilani, Hyderabad Campus Acc. No : 41093 Call No : 006.31 BUR-S machine learning is an intimidating subject until you know the fundamentals. If you understand basic coding concepts, This introductory guide will help you gain a solid foundation in machine learning principles. Using the R programming language, you'll first start to learn with regression modelling and then move into more advanced topics such as neural networks and tree-based methods. Finally, you'll delve into the frontier of machine learning, using the 'caret package in R. Once you develop a familiarity with topics such as the difference between regression and classification models, you'll be able to solve an array of machine learning problems.