1. Title Page

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Solitaire+ Download Apk Free Solitaire+ Download Apk Free

solitaire+ download apk free Solitaire+ download apk free. Completing the CAPTCHA proves you are a human and gives you temporary access to the web property. What can I do to prevent this in the future? If you are on a personal connection, like at home, you can run an anti-virus scan on your device to make sure it is not infected with malware. If you are at an office or shared network, you can ask the network administrator to run a scan across the network looking for misconfigured or infected devices. Another way to prevent getting this page in the future is to use Privacy Pass. You may need to download version 2.0 now from the Chrome Web Store. Cloudflare Ray ID: 67e2c7b2b83184e0 • Your IP : 188.246.226.140 • Performance & security by Cloudflare. 250+ Solitaire Collection Apk. Do you like to play the game on your android device? 250+solitaire collection includes favorite solitaire games consisting of Freecell, Klondike, golf; Canfield, Spider, Scorpion, Tri-Peaks, pyramid, and others, as well as a lot of original games. If you want to play a game developer gives you a demo. 250 solitaire collection you can see here playing card games with a free demo attached step-by-step of-step solitaire guide. 250+ solitaire collection apk has a textual content description of the rules for each staying power game. You can able to modify the guidelines of most solitaire games. 250 solitaire collection android download you can create a brand new solitaire recreation of types: Freecell, Klondike, Scorpion, Pyramid, Pyramid, Algerian Patience, and Golf. -

Echo and Influence Violin Concertos by Franz Clement in the Gravitation Field of Beethoven

Echo and Influence Violin Concertos by Franz Clement in the Gravitation Field of Beethoven World premier recording by Mirijam Contzen and Reinhard Goebel For the opening of Sony Classical’s „Beethoven’s World“ series Franz Joseph Clement (1780-1842) CONCERTO NO. 1 IN D-MAJOR FOR VIOLIN AND ORCHESTER (1805) [1] ALLEGRO MAESTOSO [2] ADAGIO [3] RONDO. ALLEGRO CONCERTO N. 2 IN D-MINOR FOR VIOLIN AND ORCHESTER (AFTER 1806) (WORLD PREMIER RECORDING) [4] MODERATO [5] ADAGIO [6] RONDO. ALLEGRO WDR Symphony Orchestra // Reinhard Goebel (Conductor) Mirijam Contzen (Violin) Sony Classical 19075929632 // Release (Germany): 10th of January 2020 For many years violinist Mirijam Contzen has supported the conductor and expert for historical performance practice Reinhard Goebel in his efforts to reintroduce audiences to 18th and early 19th century compositions: works that for decades have resided in the shadows, lost and forgotten, amongst the ample works preserved in various musical archives. The recordings of the Violin Concertos Nos. 1 and 2 by Viennese virtuoso Franz Joseph Clement (1780-1842) mark the rediscovery of such treasures. Together with the WDR Symphony Orchestra, Contzen and Goebel will kick-off the quintuple series „Beethoven’s World“, curated by Goebel himself, which will be released by Sony Classical throughout 2020 - the year of Beethoven’s 250th birthday anniversary. The German release date for the first album has been set for the 10th of January and includes the world premiere recording of Clements Violin Concerto No. 2 - a work lost soon after its introduction to the public in the first decade of the 19th century. The CD series acts as Reinhard Goebel’s contribution to Beethoven’s anniversary year. -

Le Journal Intime D'hercule D'andré Dubois La Chartre. Typologie Et Réception Contemporaine Du Mythe D'hercule

Commission de Programme en langues et lettres françaises et romanes Le Journal intime d’Hercule d’André Dubois La Chartre. Typologie et réception contemporaine du mythe d’Hercule Alice GILSOUL Mémoire présenté pour l’obtention du grade de Master en langues et lettres françaises et romanes, sous la direction de Mme. Erica DURANTE et de M. Paul-Augustin DEPROOST Louvain-la-Neuve Juin 2017 2 Le Journal intime d’Hercule d’André Dubois La Chartre. Typologie et réception contemporaine du mythe d’Hercule 3 « Les mythes […] attendent que nous les incarnions. Qu’un seul homme au monde réponde à leur appel, Et ils nous offrent leur sève intacte » (Albert Camus, L’Eté). 4 Remerciements Je tiens à remercier Madame la Professeure Erica Durante et Monsieur le Professeur Paul-Augustin Deproost d’avoir accepté de diriger ce travail. Je remercie Madame Erica Durante qui, par son écoute, son exigence, ses précieux conseils et ses remarques m’a accompagnée et guidée tout au long de l’élaboration de ce présent mémoire. Mais je me dois surtout de la remercier pour la grande disponibilité dont elle a fait preuve lors de la rédaction de ce travail, prête à m’aiguiller et à m’écouter entre deux taxis à New-York. Je remercie également Monsieur Paul-Augustin Deproost pour ses conseils pertinents et ses suggestions qui ont aidé à l’amélioration de ce travail. Je le remercie aussi pour les premières adresses bibliographiques qu’il m’a fournies et qui ont servi d’amorce à ma recherche. Mes remerciements s’adressent également à mes anciens professeurs, Monsieur Yves Marchal et Madame Marie-Christine Rombaux, pour leurs relectures minutieuses et leurs corrections orthographiques. -

Goethe-Handbuch Supplemente

Goethe-Handbuch Supplemente Band 1: Musik und Tanz in den Bühnenwerken Bearbeitet von Gabriele Busch-Salmen, Manfred Wenzel, Andreas Beyer, Ernst Osterkamp 1. Auflage 2008. Buch. xv, 562 S. Hardcover ISBN 978 3 476 01846 5 Format (B x L): 17 x 24,4 cm Gewicht: 1164 g Weitere Fachgebiete > Literatur, Sprache > Literaturwissenschaft: Allgemeines > Einzelne Autoren: Monographien & Biographien Zu Inhaltsverzeichnis schnell und portofrei erhältlich bei Die Online-Fachbuchhandlung beck-shop.de ist spezialisiert auf Fachbücher, insbesondere Recht, Steuern und Wirtschaft. Im Sortiment finden Sie alle Medien (Bücher, Zeitschriften, CDs, eBooks, etc.) aller Verlage. Ergänzt wird das Programm durch Services wie Neuerscheinungsdienst oder Zusammenstellungen von Büchern zu Sonderpreisen. Der Shop führt mehr als 8 Millionen Produkte. 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 2 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 3 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 118136_GoetheHB.indb8136_GoetheHB.indb I 003.07.20083.07.2008 117:10:437:10:43 UUhrhr 1 Theaterpraxis in Weimar lichen, unbeschreiblichen Verdiensten«3, das der ersten Aufführung vorausging und dem Singspiel bereits im Vorfeld die Einlösung der Neukon- zeption eines deutschsprachigen Musiktheaters Vorbemerkung prophezeite.4 Das mochte auch Goethe bewogen haben, sich mit seinem Dramolett unter die Kri- Mit dem Eintreffen Johann Wolfgang Goethes tiker zu reihen und zu signalisieren, daß er in in Weimar am 7. November 1775 begann für die der Frage einer künftigen deutschsprachigen kleine Residenzstadt eine neue Ära. Er hatte Oper durchaus eigene Wege beschreiten wolle. seine geplante erste Reise nach Italien in Hei- Dem von Wieland propagierten »regelmäßigen delberg abgebrochen und war der Einladung des Theater« hatte er bereits 1771 in seinem Genie- um einige Jahre jüngeren Herzogs Carl August Manifest Zum Schäkespears Tag eine Absage er- gefolgt. -

Keyboard Arrangements of Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully: Introduction

Keyboard Arrangements of Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully, ed. David Chung, 2014 Introduction, p. i Abbreviations Bonfils 1974 Bonfils, Jean, ed. Livre d’orgue attribué à J.N. Geoffroy, Le Pupitre: no. 53. Paris: Heugel, 1974. Chung 1997 Chung, David. “Keyboard Arrangements and Their Significance for French Harpsichord Music.” 2 vols. PhD diss., University of Cambridge, 1997. Chung 2004 Chung, David, ed. Jean-Baptiste Lully: 27 brani d’opera transcritti per tastiera nei secc. XVII e XVIII. Bologna: UT Orpheus Edizioni, 2004. Gilbert 1975 Gilbert, Kenneth, ed. Jean-Henry d’Anglebert, Pièces de clavecin, Le Pupitre: no. 54. Paris: Heugel, 1975. Gustafson 1979 Gustafson, Bruce. French Harpsichord Music of the 17th Century: A Thematic Catalog of the Sources with Commentary. 3 vols. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1979. Gustafson 2007 Gustafson, Bruce. Chambonnières: A Thematic Catalogue—The Complete Works of Jacques Champion de Chambonnières (1601/02–72), JSCM Instrumenta 1, 2007, r/2011. (http://sscm- jscm.org/instrumenta_01). Gustafson-Fuller 1990 Gustafson, Bruce and David Fuller. A Catalogue of French Harpsichord Music 1699-1780. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1990. Harris 2009 Harris, C. David, ed. Jean Henry D’Anglebert: The Collected Works. New York: The Broude Trust, 2009. Howell 1963 Howell, Almonte Charles Jr., ed. Nine Seventeenth-Century Organ Transcriptions from the Operas of Lully. Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1963. LWV Schneider, Herbert. Chronologisch-Thematisches Verzeichnis sämtlicher Werke von Jean-Baptiste Lully. Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1981. WEB LIBRARY OF SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY MUSIC (www.sscm-wlscm.org) Monuments of Seventeenth-Century Music Vol. 1 Keyboard Arrangements of Music by Jean-Baptiste Lully, ed. -

Turkish-German Rap and Threatening Masculinity

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2020 Schieß, Bruder: Turkish-German Rap and Threatening Masculinity Manasi Deorah Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Ethnomusicology Commons, European History Commons, Modern Languages Commons, Near Eastern Languages and Societies Commons, Other German Language and Literature Commons, and the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Deorah, Manasi, "Schieß, Bruder: Turkish-German Rap and Threatening Masculinity" (2020). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 1568. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/1568 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Schieß, Bruder: Turkish-German Rap and Threatening Masculinity A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Bachelor of Arts in German Studies from The College of William and Mary by Manasi N. Deorah Accepted for High Honors (Honors, High Honors, Highest Honors) ______________________________________ Prof. Jennifer Gully, Director ________________________________________ Prof. Veronika Burney ______________________________ Prof. Anne Rasmussen Williamsburg, VA May 7, 2020 Deorah 2 Table of Contents Introduction 3 Part 1: Rap and Cultural -

An Analysis of Honegger's Cello Concerto

AN ANALYSIS OF HONEGGER’S CELLO CONCERTO (1929): A RETURN TO SIMPLICITY? Denika Lam Kleinmann, B.M., M.M. Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS May 2014 APPROVED: Eugene Osadchy, Major Professor Clay Couturiaux, Minor Professor David Schwarz, Committee Member Daniel Arthurs, Committee Member John Holt, Chair of the Division of Instrumental Studies James Scott, Dean of the School of Music Mark Wardell, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Kleinmann, Denika Lam. An Analysis of Honegger’s Cello Concerto (1929): A Return to Simplicity? Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), May 2014, 58 pp., 3 tables, 28 examples, 33 references, 15 titles. Literature available on Honegger’s Cello Concerto suggests this concerto is often considered as a composition that resonates with Les Six traditions. While reflecting currents of Les Six, the Cello Concerto also features departures from Erik Satie’s and Jean Cocteau’s ideal for French composers to return to simplicity. Both characteristics of and departures from Les Six examined in this concerto include metric organization, thematic and rhythmic development, melodic wedge shapes, contrapuntal techniques, simplicity in orchestration, diatonicism, the use of humor, jazz influences, and other unique performance techniques. Copyright 2014 by Denika Lam Kleinmann ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………………..iv LIST OF MUSICAL EXAMPLES………………………………………………………………..v CHAPTER I: INTRODUCTION………..………………………………………………………...1 CHAPTER II: HONEGGER’S -

God's Suicide, by Harmony Holiday

God’s Suicide by Harmony Holiday Photo credit: James Baldwin, God Is Love, New York, 1963. Courtesy of Steve Shapiro and Fahey/Klein Gallery. © 1963, Steve Shapiro. Preface to James Take Me to the Water Baldwin’s Unwritten Corsica, October, 1956, some jittering brandy. Billie Holiday is on the phonograph serenading a petit gathering of lovers and friends. Baldwin and Suicide Note his current lover, Arnold, have become taciturn and cold with one another and Arnold has announced that he plans to leave for Paris, where he wants Essay by Harmony Holiday to study music and escape the specter of an eternity with Jimmy—he feels Originally Published August 9, 2018 possessed or dispossessed or both by their languid love affair. This kind of by The Poetry Foundation. hyper-domestic intimacy followed by dysfunction and unravelling had marked Baldwin’s love life and seemed to prey upon him, turning his tenderness into a haunt, a liability. Baldwin made his way upstairs while Arnold and the others continued in the living room, and he absconded the house by way of the rooftop, leapt down, and stumbled through a briar patch to the sea, finished his brandy and tossed the glass in before he himself walked toward a final resting place, ready to let that water take him under, having amassed enough heartache to crave an alternate consciousness, a black slate. But at the last minute, hip-deep in the water, as if he had been hallucinating and a spark of differentiation separated the real from the illusion at the height of his stupor, Baldwin changed his mind, his mandate became more vivid to him. -

Step 2025 Urban Development Plan Vienna

STEP 2025 URBAN DEVELOPMENT PLAN VIENNA TRUE URBAN SPIRIT FOREWORD STEP 2025 Cities mean change, a constant willingness to face new develop- ments and to be open to innovative solutions. Yet urban planning also means to assume responsibility for coming generations, for the city of the future. At the moment, Vienna is one of the most rapidly growing metropolises in the German-speaking region, and we view this trend as an opportunity. More inhabitants in a city not only entail new challenges, but also greater creativity, more ideas, heightened development potentials. This enhances the importance of Vienna and its region in Central Europe and thus contributes to safeguarding the future of our city. In this context, the new Urban Development Plan STEP 2025 is an instrument that offers timely answers to the questions of our present. The document does not contain concrete indications of what projects will be built, and where, but offers up a vision of a future Vienna. Seen against the background of the city’s commit- ment to participatory urban development and urban planning, STEP 2025 has been formulated in a broad-based and intensive process of dialogue with politicians and administrators, scientists and business circles, citizens and interest groups. The objective is a city where people live because they enjoy it – not because they have to. In the spirit of Smart City Wien, the new Urban Development Plan STEP 2025 suggests foresighted, intelli- gent solutions for the future-oriented further development of our city. Michael Häupl Mayor Maria Vassilakou Deputy Mayor and Executive City Councillor for Urban Planning, Traffic &Transport, Climate Protection, Energy and Public Participation FOREWORD STEP 2025 In order to allow for high-quality urban development and to con- solidate Vienna’s position in the regional and international context, it is essential to formulate clearcut planning goals and to regu- larly evaluate the guidelines and strategies of the city. -

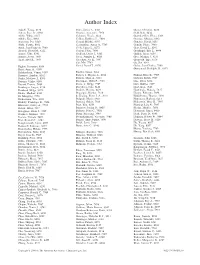

Author Index

Author Index Adachi, Yasuo, 8126 Clark, James A., 8361 Glover, Christian, 8410 Aitken, Jesse D., 8280 Cloutier, Alexandre, 7958 Gold, Ralf, 8434 Akiba, Yukio, 8327 Coleman, Nicole, 8222 Gonzalez-Rey, Elena, 8369 Alitalo, Kari, 8048 Collins, Kathleen L., 7804 Gorospe, Myriam, 8342 Anderson, Per, 8369 Conrad, Heinke, 8135 Goucher, David, 8231 Araki, Yasuto, 8102 Constantino, Agnes A., 7783 Gourdy, Pierre, 7980 Arnal, Jean-Franc¸ois, 7980 Cook, James L., 8272 Gray, David L., 8241 Aronoff, David M., 8222 Coulon, Flora, 7898 Greidinger, Eric L., 8444 Atasoy, Ulus, 8342 Crofford, Leslie J., 8361 Griffith, Jason, 8250 August, Avery, 7869 Cross, Jennifer L., 8020 Gros, Marilyn J., 8153 Azad, Abul K., 7847 Crowther, Joy E., 7847 Grunwald, Ingo, 8176 Cui, Min, 7783 Gu, Jun, 8011 Bagley, Jessamyn, 8168 Curiel, David T., 8126 Gue´ry, Jean-Charles, 7980 Bajer, Anna A., 8109 Guinamard, Rodolphe R., 8153 Balakrishnan, Vamsi, 8159 Daefler, Simon, 8262 Banerjee, Anirban, 8192 Damen, J. Mirjam A., 8184 Haddad, Elias K., 7969 Banks, Matthew I., 8393 Daniels, Mark A., 8211 Halwani, Rabih, 7969 Baranyi, Ulrike, 8168 Davenport, Miles P., 7938 Hao, Yibai, 8222 Bayard, Francis, 7980 Davis, T. Gregg, 7989 Hara, Hideki, 7859 Bernhagen, Jurgen, 8250 Davydova, Julia, 8126 Hase, Koji, 7840 Bernhard, Helga, 8135 Deckert, Martina, 8421 Hashimoto, Makoto, 7827 Bhatia, Madhav, 8333 Degauque, Nicolas, 7818 Haspot, Fabienne, 7898 Bi, Mingying, 7793 de Koning, Pieter J. A., 8184 Haudebourg, Thomas, 7898 Biedermann, Tilo, 8040 Delgado, Mario, 8369 Hausmann, Barbara, 8211 Blakely, -

Building an Unwanted Nation: the Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Carolina Digital Repository BUILDING AN UNWANTED NATION: THE ANGLO-AMERICAN PARTNERSHIP AND AUSTRIAN PROPONENTS OF A SEPARATE NATIONHOOD, 1918-1934 Kevin Mason A dissertation submitted to the faculty of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of PhD in the Department of History. Chapel Hill 2007 Approved by: Advisor: Dr. Christopher Browning Reader: Dr. Konrad Jarausch Reader: Dr. Lloyd Kramer Reader: Dr. Michael Hunt Reader: Dr. Terence McIntosh ©2007 Kevin Mason ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii ABSTRACT Kevin Mason: Building an Unwanted Nation: The Anglo-American Partnership and Austrian Proponents of a Separate Nationhood, 1918-1934 (Under the direction of Dr. Christopher Browning) This project focuses on American and British economic, diplomatic, and cultural ties with Austria, and particularly with internal proponents of Austrian independence. Primarily through loans to build up the economy and diplomatic pressure, the United States and Great Britain helped to maintain an independent Austrian state and prevent an Anschluss or union with Germany from 1918 to 1934. In addition, this study examines the minority of Austrians who opposed an Anschluss . The three main groups of Austrians that supported independence were the Christian Social Party, monarchists, and some industries and industrialists. These Austrian nationalists cooperated with the Americans and British in sustaining an unwilling Austrian nation. Ultimately, the global depression weakened American and British capacity to practice dollar and pound diplomacy, and the popular appeal of Hitler combined with Nazi Germany’s aggression led to the realization of the Anschluss . -

Outstanding Commissioners

Outstanding Soil and Water Conservation District Commissioner Past Recipients The awards program for Outstanding Soil Conservation District Commissioners began in 1952 with sponsorship from Radio Station WMT. 1952 1956 (sponsored by KXEL, Waterloo) 1 - Ralph Wilcox, Correctionville (Woodbury) 1 - Everett Rice, Storm Lake (Buena Vista) 2 - Guy Wooster, Mapleton (Monona) 2 - Harvey Sornson, Audubon (Audubon) 3 - Ralph Long, Mount Ayr (Ringgold) 3 - Ted Turner, Corning (Adams) 4 - J. C. Skow, Wesley (Kossuth) 4 - John Edwards, Humboldt (Humboldt) 5 - Forrest Hill, Dysart (Tama) 5 - Bruce Bennett, West Des Moines (Polk) 6 - P. W. Spilman, Bloomfield (Davis) 6 - Arlo Noble, Seymour (Wayne) 7 - Garland Byrnes, Dorchester (Allamakee) 7 - Ole Embretson, St. Olaf (Clayton) 8 - Arthur Satterlee,Independence (Buchanan) 8 - John Garner, Davenport (Scott) 9 - Roy White, Salem (Henry) 9 - Clifford Streigle, Delta (Keokuk) 1953 (sponsored by KFMY & KVFD, 1957 (sponsored by Honegger's Feed Fort Dodge; SSCC; IASCDC) Company, Inc.) 1 - Lawrence Everly, Lawton (Woodbury) 1 - Lyle Fogelman, Sutherland (O'Brien) 2 - Wilbur Peters, Persia (Harrison) 2 - C. E. Rich, Glidden (Carroll) 3 - Alvin Peterson, Stanton (Montgomery) 3*- Dallas McGrew, Emerson (Mills) 4 - Lloyd Crom, Chapin (Franklin) 4 - Andrew Christensen, Dows (Franklin) 5 - Howard Sears, Malcom (Poweshiek) 5 - J. Merrill Anderson, Newton (Jasper) 6 - Gilbert Fridley, Indianola (Warren) 6 - Vogel Smith, Russell (Lucas) 7 - Leo Herold, Ft. Atkinson (Winneshiek) 7 - J. Fred Ingels, Maynard (Fayette)