Service-Learning in the Era of “New Normal”: Reflection on the Modes of Service-Learning and Future Partnerships

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Jessup Global Rounds Full Team List (Alphabetical Order)

———— 2021 Jessup Global Rounds Full Team List (Alphabetical Order) ———— Please find a full list of every Jessup team competing in the 2021 Global Rounds in alphabetical order by country and then university below. The order in which teams appear on this list does not reflect any sort of ranking. Team No. Team (Country – University) 670 Afghanistan - American University of Afghanistan 516 Afghanistan - Balkh University 261 Afghanistan - Faryab University 491 Afghanistan - Herat University 352 Afghanistan - Jami University 452 Afghanistan - Jozjan University 574 Afghanistan - Kabul University 263 Afghanistan - Kandahar University 388 Afghanistan - Kardan University 372 Afghanistan - Khost University 300 Afghanistan - Kunar University 490 Afghanistan - Kunduz University 619 Afghanistan - Nangarhar University 262 Afghanistan - Paktia University 715 Albania - EPOKA University 293 Albania - Kolegji Universitar “Bedër” 224 Argentina - Universidad de Buenos Aires 205 Argentina - Universidad Nacional de Córdoba 217 Argentina - Universidad Torcuato di Tella 477 Australia - Australian National University 476 Australia - Bond University 323 Australia - La Trobe University 322 Australia - Macquarie University 218 Australia - Monash University 264 Australia - Murdoch University 591 Australia - University of Adelaide 659 Australia - University of Melbourne 227 Australia - University of NeW South Wales 291 Australia - University of Queensland 538 Australia - University of Southern Queensland 248 Australia - University of Sydney 626 Australia - University -

Partner Universities

Partner universities : 1. Argentine-Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina, Santa María de los Buenos Aires 2. Argentine-Universidad Católica de Córdoba 3. Argentine-Universidad Católica de Santa Fé 4. Australie-Australian Catholic University 5. Australie-Charles Sturt University 6. Australie-Queensland University of Technology 7. Australie-The University of Queensland 8. Bosnie-Herzégovine-International Burch University 9. Bosnie-Herzégovine-International University of Sarajevo 10. Bosnie-Herzégovine-Univerzitet u Sarajevu 11. Brésil-Pontificia Universidade Católica de Minas Gerais (PUC Minas) 12. Brésil-PontifIcia Universidade Católica do Paraná (PUCPR) 13. Brésil-Universidade de Ribeirão Preto (UNAERP) 14. Canada-KING'S COLLEGE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF WESTERN ONTARIO 15. Canada-Saint Paul University 16. Canada-University of Alberta 17. Canada-University of Ottawa 18. Canada-University of the Fraser Valley 19. Chili-Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile 20. Chili-Universidad Mayor 21. Chili-Universidad Técnica Federico Santa María 22. Chine-Shanghai International Studies University (SISU) 23. Chine-The Chinese University of Hong Kong 24. Chine-United International College - Beijing Normal University-Hong Kong Baptist University 25. Chine-University of Saint-Joseph 26. Chine-Wuhan University 27. Colombie-Pontificia Universidad Javeriana Bogota 28. Colombie-Pontificia Universidad Javeriana de Cali 29. Colombie-Universidad del Rosario 30. Corée, République de-Catholic University of Korea 31. Corée, République de-Ewha Womans University 32. Corée, République de-Inha University 33. Corée, République de-Sejong University 34. Corée, République de-Sogang University 35. Corée, République de-Sungkyunkwan University 36. Équateur-Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador 37. Équateur-Universidad San Francisco de Quito 38. États-Unis-Canisius College 39. États-Unis-Catholic University Of America 40. -

Thomas John Hastings Professional Experience

Engaging in Mission with the World Christian Movement Since 1922 THOMAS JOHN HASTINGS [email protected] PROFESSIONAL EXPERIENCE EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR & EDITOR August, 2016–Present Overseas Ministries Study Center & International Bulletin of Mission Research New Haven, Connecticut RESEARCH CONSULTANT 2015–2016 United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia, New York SENIOR RESEARCH FELLOW 2012–2015 Japan International Christian University Foundation, New York, NY Recipient of a 3-year grant award from the John Templeton Foundation entitled “Advancing the Science and Religion Conversation in Japan” Grant-related academic appointments in Japan: Research Fellow 2012–Present Kagawa Archives and Resource Center, Tokyo Research Associate 2012–2016 Nanzan Institute for Religion and Culture, Nagoya Research Fellow 2013–2016 Institute for the Study of Christianity and Culture, International Christian University, Tokyo Cooperating Researcher 2014–2016 Kokoro Research Center, Kyoto University, Kyoto DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH, ASSOCIATE DIRECTOR, RESEARCH FELLOW 2008–2012 Center of Theological Inquiry, Princeton, New Jersey MISSION CO-WORKER, PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH (USA) 1988-2008 PROFESSOR OF PRACTICAL THEOLOGY 1995–2008 Tokyo Union Theological Seminary, Tokyo, Japan ASSOCIATE PROFESSOR OF CHRISTIAN EDUCATION 1993–1995 Seiwa College, Nishinomiya, Japan LECTURER & DIRECTOR OF FOREIGN FACULTY 1987–1991 Hokuriku Gakuin University, Kanazawa, Japan OTHER TEACHING EXPERIENCE • Adjunct 2017– Yale Divinity School, New Haven, Connecticut • Adjunct Fall Semester -

Unai Members List August 2021

UNAI MEMBER LIST Updated 27 August 2021 COUNTRY NAME OF SCHOOL REGION Afghanistan Kateb University Asia and the Pacific Afghanistan Spinghar University Asia and the Pacific Albania Academy of Arts Europe and CIS Albania Epoka University Europe and CIS Albania Polytechnic University of Tirana Europe and CIS Algeria Centre Universitaire d'El Tarf Arab States Algeria Université 8 Mai 1945 Guelma Arab States Algeria Université Ferhat Abbas Arab States Algeria University of Mohamed Boudiaf M’Sila Arab States Antigua and Barbuda American University of Antigua College of Medicine Americas Argentina Facultad de Ciencias Económicas de la Universidad de Buenos Aires Americas Argentina Facultad Regional Buenos Aires Americas Argentina Universidad Abierta Interamericana Americas Argentina Universidad Argentina de la Empresa Americas Argentina Universidad Católica de Salta Americas Argentina Universidad de Congreso Americas Argentina Universidad de La Punta Americas Argentina Universidad del CEMA Americas Argentina Universidad del Salvador Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Avellaneda Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cordoba Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Cuyo Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Jujuy Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de la Pampa Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Quilmes Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Rosario Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de Santiago del Estero Americas Argentina Universidad Nacional de -

2009 Participating Teams Philip C. Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition

2009 Participating Teams Philip C. Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition Teams that competed at the Shearman & Sterling International Rounds are indicated in bold. Exhibition teams are indicated with an asterisk (*). Observing teams are indicated with a pound sign (#). AFGHANISTAN Balkh University # ALBANIA Tirana Faculty of Law ARGENTINA Universidad de Buenos Aires Universidad Nacional de Cuyo ARMENIA European Regional Educational Academy M. Nalbandyan State Pedagogical University of Gyumri National Academy of Sciences of the Republic of Armenia Vanadzor State Pedagogical Institute Yerevan State University AUSTRALIA Australian National University Bond University Macquarie University Monash University Murdoch University Queensland University of Technology University of Melbourne University of New South Wales University of Queensland University of Sydney University of Tasmania University of Technology Sydney University of Western Australia University of Western Sydney Victoria University BALTIC REGION European Humanities University BELARUS Belarusian State University International Institute of Labor & Social Relations# BELGIUM Ghent University Katholieke Universiteit Leuven * BOSNIA AND HERZEGOVINA Law Faculty Sarajevo BRAZIL Centro Universitario Ritter dos Reis (UniRitter) Direito GV Faculdades Integradas do Oeste de Minas (FADOM) Universidade Catolica de Santos Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais (UFMG) Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul (UFRGS) University of Passo Fundo University of Sao Paulo BULGARIA University of -

December 2016 United Board for Christian Higher Education in Asia

DECEMBER 2016 UNITED BOARD FOR CHRISTIAN HIGHER EDUCATION IN ASIA Opening Paths for Networking and Exchange In this issue: Our 2016 Annual Report Message from the President Harvest Time In August of this year, four young Sri Lankan students arrived to begin their studies at Madras Christian College, part of a fast-moving relationship between United Board network institutions in India and schools in the war-torn Jaffna region of northern Sri Lanka. Only four days earlier, members of the United Board’s South Asia Task Force, accompanied by a dynamic group of Indian higher education leaders, had been seated in a conference room in Jaffna, exchanging ideas with local educators about ways to strengthen the skills of faculty and enrich the educational experience of students at a time of national and regional recovery. The discussion was intended to help our task force better understand the higher education landscape in Sri Lanka, but thanks to the generous impulses of leaders from Madras Christian College, Lady Doak College, and Women’s Christian College, that conversation very quickly shifted our perspective from what we might attempt in the near future to what we can do today. Nancy E. Chapman President That experience reminds me that the future is never more than a few steps away. The actions of my South Asian “When our earlier investments are bearing colleagues demonstrate that the needs of Asian college and university fruit, we should not delay the harvest. administrators, faculty, and students are immediate – and often, some solutions are readily available. Given our modest resources, the United Board takes a thoughtful, measured approach” to developing new program areas and extending its network to new regions. -

Christite HANDBOOK

Medicinal Values: HANDBOOK 2019-2020 CHRISTITE used to cure diabetes, Botanical Name: eye related diseases like cataract, Butea Monosperma Anaemia in kids, kidney stones, (Flame of the Forest) urinary blockages and pain in bladder. Common Name: Tree Location at CHRIST: Palash, Dhak, Left of the Exit Gate near the Palah, Flame of the forest, Car Parking- Main Campus. Dhak (Hindi), Purasu (Tamil), Palasha (Sanskrit) Image Courtesy: Fr Joby Xavier, Department of Life Sciences CHRIST (Deemed to be University), Hosur Road, Bengaluru 560 029, Karnataka, India Tel: +9180 4012 9100, 9600 | Fax:+9180 4012 9000 [email protected] | www.christuniversity.in CHRIST (Deemed to be University) Faculty of Engineering Kanminike, Kumbalgodu P.O., Bengaluru 560 074, Karnataka, India Tel: +9180 4012 9800/9802/9820 | Fax:+9180 4012 9898 [email protected] | https:/ christuniversity.in/ campus/kengeri-campus 2019-20 CHRIST (Deemed to be University) School of Business Studies and Social Sciences Bannerghatta Road Campus Hulimavu, Bannerghatta Road, Bengaluru, 560076, Kamataka Ph: +9180 46551333/46551334 [email protected] | https:/ christuniversity.in/ campus/banargatta-campus CHRIST (Deemed to be University) Lavasa Campus, Christ University Road, 30 Valor Court At Post: Dasve Lavasa, Taluka: Mulshi, Pune 412112, Maharashtra. Ph: 1800-123-2009 | Fax No : 1800-123-2009 | [email protected] CHRIST (Deemed to be University) Delhi NCR Campus Mariam Nagar, Meerut Road, Delhi NCR, Ghaziabad - 201003 Ph : 1800-123-3212 | Fax No : 01202986761 | [email protected] Nodal Office, Thiruvananthapuram T.C.15/1359, AIR Road, Vazhuthacaud, Trivandrum-695014, Kerala, India HANDBOOK Tel: +91 471 2339960 | Email: [email protected] Christite Concept & Design : Centre for Publications STUDENT HANDBOOK 2019-20 Name.................................................................................................................... -

Handbook of Incoming Exchange Students 7 3 2 6 4 4 - 2

Website: www.clec.pu.edu.tw Website: Chinese Language EducationCenter E-mail: [email protected] +886-4-2664-5073 Tel: 43301, Taiwan 200 ChungChiRd.,Shalu, Taichung University Providence Office ofInternational Affairs E-mail: [email protected] www.oia.pu.edu.tw Website: Fax: +886-4-2652-6602 10110803 TEL: 04-24733326 Handbook of Exchange Exchange Incoming Students What's it like to study at About Providence University Providence University? Providence University provides a w e a l t h o f e x p e r i e n c e s f o r Providence University is a Catholic co- Taiwan, with 22 departments, 21 graduate programs, 2 Ph.D. educational institution founded in 1956 by programs, 5 EMBA programs, and one Chinese Language students from all over the world an American congregation: the Sisters of Education Center. Volunteer Service is the core value of the campus who have this to say: Providence of Saint Mary-of-the-Woods, through which teachers and students create a focus on teaching, Indiana, USA. The university's roots can be respect for life, attention to moral character, and willingness to traced back to 1920 in Mainland China. It serve. Approximately 12,000 undergraduate students and 1,200 An atmosphere of academic is now sponsored by the Catholic Diocese graduate students are enrolled, taught by 400 full-time faculty of Taichung. members. excitement Because of its location in Taichung City, students enjoy clean air and expansive For further information, please visit the following web pages. “I especially commend Professor Peng on Strategic Management because of her advanced green vistas in a teaching style of letting the students have the chance to take part in real business. -

United Board Fellows Program

United Board Fellows Program 2017-2018 List of Eligible Institutions This is a list indicating the home institutions which have a previous Fellow. Those that are not on the list but are interested in this program could contact our staff for inquiries related to the institutional eligibility at [email protected]. Please note that eligible institutions should have at least participated in one of the following United Board programs in the past: United Board Fellows Program, United Board Faculty Scholarship Program, Asia University Leaders Program, and Small Grants and/or Institutional Grants Program. CAMBODIA Royal University of Phnom Penh CHINA Central China Normal University, Wuhan Fudan University, Shanghai Ginling College, Nanjing Guizhou Normal University, Guiyang Hwanan Women’s College, Fuzhou Nanjing University, Nanjing Renmin University, Beijing Shaanxi Normal University, Xi’an Shanghai University, Shanghai Sichuan University, Chengdu Yanbian University, Yanji Yunnan University, Kunming Zhejiang University, Hangzhou HONG KONG Hong Kong Baptist University INDIA American College, Madurai Christ University, Bangalore Isabella Thoburn College, Lucknow Karunya University, Coimbatore Lady Doak College, Madurai Madras Christian College, Chennai Salesian College, West Bengal Scottish Church College, Kolkata Stella Maris College, Chennai Union Christian College, Kerala Women’s Christian College, Chennai INDONESIA Artha Wacana Christian University, Kupang, West Timor Atma Jaya University, Yogyakarta, Java Duta Wacana Christian University, -

Aith, M the Your Als

Have Faith, break from the cocoon and unleash your potentials. Department of Management Studies CHRIST (Deemed to be University) Hosur Road, Bengaluru - 560 029, Karnataka, India Tel : +91-80-4012 9100 Fax : +91-80-4012 9000 www.christuniversity.in Just like space, the capacity of the human mind is unfathomable yet we outline our own confinements, and settle within the bounds of our suppositions. We vanquish the barriers by unshackling the avidity for triumph, Our Special Thanks to the key to which is the human mind itself. Dr Fr Joby Xavier, Chief Finance Officer Dr Fr Biju K Chacko, Director, Media Studies The rising sun manifests a new dawn, Dr Anupama Nayar CV, Head, Centre for Concept Design a new genesis of opportunities waiting for us Mr Kashinath K, Centre for Publication to be explored. To look at every endeavour, Coordinators and Faculty, Department of Management Studies regard every morning and every day as the Mr Johney John, Mr Siju Govindh and Ms Lakshmi, National Printing Press beginning of a new life in which we have the opportunity to think, feel, act, and live anew as every ending is creating the space and opening for new beginnings. (Backpage Photograph Credits - Ayush Soni) (Only for Internal Circulation) | The Eternal Quest of a Human Being is to shatter the constraints of ungratefulness. | Table of Contents Department of Management Studies ..................... 1 Note from the Editorial Board ............................... 3 The Vice Chancellor ................................................ 5 The Associate Dean .............................................. 6 The Head of the Department ................................... 7 The Editor (Faculty) ............................................ 8 The Editor (Faculty) ............................................ 9 Co-curricular Aspects of the Department .............. -

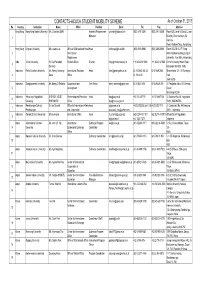

CONTACTS-ACUCA STUDENT MOBILITY SCHEME As of October 31, 2013 No

CONTACTS-ACUCA STUDENT MOBILITY SCHEME As of October 31, 2013 No. Country Institution Name Office Position Email Tel. Fax. Address Hong Kong Hong Kong Baptist University Ms. Christina CHAN Assistant Programmem [email protected] (852) 3411 5328 (852) 3411 5568 Room 825, Level 8, David C. Lam Manager Building, Shaw Campus, 34 1 Renfrew Road, Kowloon Tong, Hong Kong Hong Kong Lingnan University Ms. Joanne Lai Office of Mainland and Head Head [email protected] (852) 2616-8990 (852) 2465-9660 Room AD-208/1, 2/F, Wong 2 International Administration Building, Lingnan Programmes University, Tuen Mun, Hong Kong India Christ University Fr. Viju Painadath Student Affairs Director [email protected] + 91 80 4012 9008 +91 80 4012 9000 Christ University, Hosur Road, 3 Devassy Bangalore 560 029 , India Indonesia Petra Christian University Ms. Renny Novemsy International Relations Head [email protected] 62 31 298 3185, 62 62 31 849 2583 Siwalankerto 121-131 Surabaya, 4 Dese Office 31 298 3187 East Java 60236 Indonesia Soegijapranata University Mr. Benny D Setianto Cooperation and Vice Rector [email protected] 62 24 8441 555 62 24 8445 265 Jl. Pawiyatan Luhur IV/I Bendan 5 Development Duwur Semarang 50234 Indonesia Atma Jaya Yogyakarta M.SI IGN. AGUS Partnership and Promotion Head [email protected] +62 274 487711 +62 274 487748 Jl. Babarsari No. 44 Yogyakarta 6 University PUTRANTO Office [email protected] 55281, INDONESIA Indonesia Parahyangan Catholic Dr. Ida Susanti Office for International AffairsHead [email protected] +62222032655 (ext 125)+62222031110 Jl. Ciumbuleuit No. -

UB Horizons Dec 2019 1122 OP.Indd

DECEMBER 2019 UNITED BOARD FOR CHRISTIAN HIGHER EDUCATION IN ASIA 100 Years and Beyond In this issue: Our 2019 Annual Report Message from the Chair & President Our Second Century Comes into Focus Welcome to a season of celebration! With this issue of Horizons, we are launching the United Board’s multiyear centennial celebration. The United Board was founded in October 1922, so we officially turn 100 in October 2022. In anticipation of this joyous event, we plan to extend the celebration over the course of several years so as to multiply the opportunities for us to share this milestone with the many colleagues, supporters, and friends who are so important to our mission and programs. “Great Expectations” is the theme that unifies our wide-ranging plans for observing the centennial. “Great Expectations” defines both our heritage and our outlook for the future. It recognizes that the United Board has been a forward-looking organization from its earliest days, when a small number of ambitious and determined missionary educators endeavored to introduce new approaches to higher education in Asia. It describes the Judith A. Berling aspirations of the leaders and faculty of our network institutions, who translate the Chair principles of whole person education into practice. And it captures the anticipation of eager students as they first arrive on campus and as they graduate and embark upon the initial stages of their careers and adult lives. Great expectations also are evident in the strategic priorities that United Board trustees and staff have defined to guide us into our second century. A number of them, described on the next page, show the pathways for turning our vision of whole person education into action.