Supplemental Material Table 1A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Remaking Italy? Place Configurations and Italian Electoral Politics Under the ‘Second Republic’

Modern Italy Vol. 12, No. 1, February 2007, pp. 17–38 Remaking Italy? Place Configurations and Italian Electoral Politics under the ‘Second Republic’ John Agnew The Italian Second Republic was meant to have led to a bipolar polity with alternation in national government between conservative and progressive blocs. Such a system it has been claimed would undermine the geographical structure of electoral politics that contributed to party system immobilism in the past. However, in this article I argue that dynamic place configurations are central to how the ‘new’ Italian politics is being constructed. The dominant emphasis on either television or the emergence of ‘politics without territory’ has obscured the importance of this geographical restructuring. New dynamic place configurations are apparent particularly in the South which has emerged as a zone of competition between the main party coalitions and a nationally more fragmented geographical pattern of electoral outcomes. These patterns in turn reflect differential trends in support for party positions on governmental centralization and devolution, geographical patterns of local economic development, and the re-emergence of the North–South divide as a focus for ideological and policy differences between parties and social groups across Italy. Introduction One of the high hopes of the early 1990s in Italy was that following the cleansing of the corruption associated with the party regime of the Cold War period, Italy could become a ‘normal country’ in which bipolar politics of electoral competition between clearly defined coalitions formed before elections, rather than perpetual domination by the political centre, would lead to potential alternation of progressive and conservative forces in national political office and would check the systematic corruption of partitocrazia based on the jockeying for government offices (and associated powers) after elections (Gundle & Parker 1996). -

November 2020

EPP Party Barometer November 2020 The Situation of the European People’s Party in the EU (as of: 23 November 2020) Dr Olaf Wientzek (Graphic template: Janine www.kas.de Höhle, HA Kommunikation, Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung) Summary & latest developments (I) • In national polls, the EPP family are the strongest political family in 12 countries (including Fidesz); the Socialist political family in 6, the Liberals/Renew in 4, far-right populists (ID) in 2, and the Eurosceptic/national conservative ECR in 1. Added together, independent parties lead in Latvia. No polls/elections have taken place in France since the EP elections. • The picture is similar if we look at the strongest single party and not the largest party family: then the EPP is ahead in 12 countries (if you include the suspended Fidesz), the Socialists in 7, the Liberals in 4, far-right populists (ID) in 2, and the ECR in one land. • 10 (9 without Orbán) of the 27 Heads of State and Government in the European Council currently belong to the EPP family, 7 to the Liberals/Renew, 6 to the Social Democrats / Socialists, 1 to the Eurosceptic conservatives, and 2 are formally independent. The party of the Slovak head of government belongs to the EPP group but not (yet) to the EPP party; if you include him in the EPP family, there would be 11 (without Orbán 10). • In many countries, the lead is extremely narrow, or, depending on the polls, another party family is ahead (including Italy, Sweden, Latvia, Belgium, Poland). Summary & latest developments (II) • In Romania, the PNL (EPP) has a good starting position for the elections (Dec. -

The Political Context of Eu Accession in Hungary

European Programme November 2002 THE POLITICAL CONTEXT OF EU ACCESSION IN HUNGARY Agnes Batory Introduction For the second time since the adoption of the Maastricht Treaty – seen by many as a watershed in the history of European integration – the European Union (EU) is set to expand. Unlike in 1995, when the group joining the Union consisted of wealthy, established liberal democracies, ten of the current applicants are post-communist countries which recently completed, or are still in various stages of completing, democratic transitions and large-scale economic reconstruction. It is envisaged that the candidates furthest ahead will become members in time for their citizens to participate in the next elections to the European Parliament due in June 2004. The challenge the absorption of the central and east European countries represents for the Union has triggered a need for internal institutional reform and new thinking among the policy-makers of the existing member states. However, despite the imminence of the ‘changeover’ to a considerably larger and more heterogeneous Union, the domestic profiles of the accession countries have remained relatively little known from the west European perspective. In particular, the implications of enlargement in terms of the attitudes and preferences of the new (or soon to be) players are still, to a great extent, unclear. How will they view their rights and obligations as EU members? How committed will they be to the implementation of the acquis communautaire? In what way will they fill formal rules with practical content? BRIEFING PAPER 2 THE POLITICAL CONTEXT OF EU ACCESSION IN HUNGARY Naturally, the answers to these questions can only government under the premiership of Miklós Németh be tentative at this stage. -

Political Thought No. 60

POLITICAL THOUGHT YEAR 18, No 60, NOVEMBER, SKOPJE 2020 Publisher: Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Republic of North Macedonia Institute for Democracy “Societas Civilis”, Skopje Founders: Dr. Gjorge Ivanov, Andreas Klein M.A. Politička misla - Editorial Board: Norbert Beckmann-Dierkes Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Germany Nenad Marković Institute for Democracy “Societas Civilis”, Political Science Department, Faculty of Law “Iustinianus I”, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia Ivan Damjanovski Institute for Democracy “Societas Civilis”, Political Science Department, Faculty of Law “Iustinianus I”, Ss. Cyril and Methodius University in Skopje, Republic of North Macedonia Hans-Rimbert Hemmer Emeritus Professor of Economics, University of Giessen, Germany Claire Gordon London School of Economy and Political Science, England Robert Hislope Political Science Department, Union College, USA Ana Matan-Todorcevska Faculty of Political Science, Zagreb University, Croatia Predrag Cvetičanin University of Niš, Republic of Serbia Vladimir Misev OSCE Office for Democratic Institutions and Human Rights, Poland Sandra Koljačkova Konrad Adenauer Foundation, Republic of North Macedonia Address: KONRAD-ADENAUER-STIFTUNG ul. Risto Ravanovski 8 MK - 1000 Skopje Phone: 02 3217 075; Fax: 02 3217 076; E-mail: [email protected]; Internet: www.kas.de INSTITUTE FOR DEMOCRACY “SOCIETAS CIVILIS” SKOPJE Miroslav Krleza 52-1-2 MK - 1000 Skopje; Phone/ Fax: 02 30 94 760; E-mail: [email protected]; Internet: www.idscs.org.mk E-mail: [email protected] Printing: Vincent grafika - Skopje Design & Technical preparation: Pepi Damjanovski Translation: Tiina Fahrni, Perica Sardzoski Macedonian Language Editor: Elena Sazdovska The views expressed in the magazine are not views of Konrad Adenauer Foundation and the Institute for Democracy “Societas Civilis” Skopje. -

Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture

In &a r*tm Enfry Denied Aslan American History and Culture edited by Sucheng Chan Exclusion and the Chinese Communify in America, r88z-ry43 Edited by Sucheng Chan Also in the series: Gary Y. Okihiro, Cane Fires: The Anti-lapanese Moaement Temple University press in Hawaii, t855-ry45 Philadelphia Chapter 6 The Kuomintang in Chinese American Kuomintang in Chinese American Communities 477 E Communities before World War II the party in the Chinese American communities as they reflected events and changes in the party's ideology in China. The Chinese during the Exclusion Era The Chinese became victims of American racism after they arrived in Him Lai Mark California in large numbers during the mid nineteenth century. Even while their labor was exploited for developing the resources of the West, they were targets of discriminatory legislation, physical attacks, and mob violence. Assigned the role of scapegoats, they were blamed for society's multitude of social and economic ills. A populist anti-Chinese movement ultimately pressured the U.S. Congress to pass the first Chinese exclusion act in 1882. Racial discrimination, however, was not limited to incoming immi- grants. The established Chinese community itself came under attack as The Chinese settled in California in the mid nineteenth white America showed by words and deeds that it considered the Chinese century and quickly became an important component in the pariahs. Attacked by demagogues and opportunistic politicians at will, state's economy. However, they also encountered anti- Chinese were victimizedby criminal elements as well. They were even- Chinese sentiments, which culminated in the enactment of tually squeezed out of practically all but the most menial occupations in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882. -

2021 Year Ahead

2021 YEAR AHEAD Claudio Brocado Anthony Brocado January 29, 2021 1 2020 turned out to be quite unusual. What may the year ahead and beyond bring? As the year got started, the consensus was that a strong 2019 for equities would be followed by a positive first half, after which meaningful volatility would kick in due to the US presidential election. In the spirit of our prefer- ence for a contrarian stance, we had expected somewhat the opposite: some profit-taking in the first half of 2020, followed by a rally that would result in a positive balance at year-end. But in the way of the markets – which always tend to catch the largest number of participants off guard – we had what some would argue was one of the strangest years in recent memory. 2 2020 turned out to be a very eventful year. The global virus crisis (GVC) brought about by the coronavirus COVID-19 pandemic was something no serious market observer had anticipated as 2020 got started. Volatility had been all but nonexistent early in what we call ‘the new 20s’, which had led us to expect the few remaining volatile asset classes, such as cryptocurrencies, to benefit from the search for more extreme price swings. We had expected volatilities across asset classes to show some convergence. The markets delivered, but not in the direction we had expected. Volatilities surged higher across many assets, with the CBOE volatility index (VIX) reaching some of the highest readings in many years. As it became clear that what was commonly called the novel coronavirus would bring about a pandemic as it spread to the remotest corners of the world at record speeds, the markets feared the worst. -

Codebook Indiveu – Party Preferences

Codebook InDivEU – party preferences European University Institute, Robert Schuman Centre for Advanced Studies December 2020 Introduction The “InDivEU – party preferences” dataset provides data on the positions of more than 400 parties from 28 countries1 on questions of (differentiated) European integration. The dataset comprises a selection of party positions taken from two existing datasets: (1) The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File The EU Profiler/euandi Trend File contains party positions for three rounds of European Parliament elections (2009, 2014, and 2019). Party positions were determined in an iterative process of party self-placement and expert judgement. For more information: https://cadmus.eui.eu/handle/1814/65944 (2) The Chapel Hill Expert Survey The Chapel Hill Expert Survey contains party positions for the national elections most closely corresponding the European Parliament elections of 2009, 2014, 2019. Party positions were determined by expert judgement. For more information: https://www.chesdata.eu/ Three additional party positions, related to DI-specific questions, are included in the dataset. These positions were determined by experts involved in the 2019 edition of euandi after the elections took place. The inclusion of party positions in the “InDivEU – party preferences” is limited to the following issues: - General questions about the EU - Questions about EU policy - Questions about differentiated integration - Questions about party ideology 1 This includes all 27 member states of the European Union in 2020, plus the United Kingdom. How to Cite When using the ‘InDivEU – Party Preferences’ dataset, please cite all of the following three articles: 1. Reiljan, Andres, Frederico Ferreira da Silva, Lorenzo Cicchi, Diego Garzia, Alexander H. -

ESS9 Appendix A3 Political Parties Ed

APPENDIX A3 POLITICAL PARTIES, ESS9 - 2018 ed. 3.0 Austria 2 Belgium 4 Bulgaria 7 Croatia 8 Cyprus 10 Czechia 12 Denmark 14 Estonia 15 Finland 17 France 19 Germany 20 Hungary 21 Iceland 23 Ireland 25 Italy 26 Latvia 28 Lithuania 31 Montenegro 34 Netherlands 36 Norway 38 Poland 40 Portugal 44 Serbia 47 Slovakia 52 Slovenia 53 Spain 54 Sweden 57 Switzerland 58 United Kingdom 61 Version Notes, ESS9 Appendix A3 POLITICAL PARTIES ESS9 edition 3.0 (published 10.12.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Denmark, Iceland. ESS9 edition 2.0 (published 15.06.20): Changes from previous edition: Additional countries: Croatia, Latvia, Lithuania, Montenegro, Portugal, Slovakia, Spain, Sweden. Austria 1. Political parties Language used in data file: German Year of last election: 2017 Official party names, English 1. Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs (SPÖ) - Social Democratic Party of Austria - 26.9 % names/translation, and size in last 2. Österreichische Volkspartei (ÖVP) - Austrian People's Party - 31.5 % election: 3. Freiheitliche Partei Österreichs (FPÖ) - Freedom Party of Austria - 26.0 % 4. Liste Peter Pilz (PILZ) - PILZ - 4.4 % 5. Die Grünen – Die Grüne Alternative (Grüne) - The Greens – The Green Alternative - 3.8 % 6. Kommunistische Partei Österreichs (KPÖ) - Communist Party of Austria - 0.8 % 7. NEOS – Das Neue Österreich und Liberales Forum (NEOS) - NEOS – The New Austria and Liberal Forum - 5.3 % 8. G!LT - Verein zur Förderung der Offenen Demokratie (GILT) - My Vote Counts! - 1.0 % Description of political parties listed 1. The Social Democratic Party (Sozialdemokratische Partei Österreichs, or SPÖ) is a social above democratic/center-left political party that was founded in 1888 as the Social Democratic Worker's Party (Sozialdemokratische Arbeiterpartei, or SDAP), when Victor Adler managed to unite the various opposing factions. -

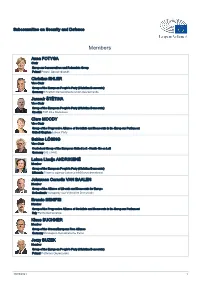

List of Members

Subcommittee on Security and Defence Members Anna FOTYGA Chair European Conservatives and Reformists Group Poland Prawo i Sprawiedliwość Christian EHLER Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Germany Christlich Demokratische Union Deutschlands Jaromír ŠTĚTINA Vice-Chair Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Czechia TOP 09 a Starostové Clare MOODY Vice-Chair Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament United Kingdom Labour Party Sabine LÖSING Vice-Chair Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Germany DIE LINKE. Laima Liucija ANDRIKIENĖ Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Lithuania Tėvynės sąjunga-Lietuvos krikščionys demokratai Johannes Cornelis VAN BAALEN Member Group of the Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe Netherlands Volkspartij voor Vrijheid en Democratie Brando BENIFEI Member Group of the Progressive Alliance of Socialists and Democrats in the European Parliament Italy Partito Democratico Klaus BUCHNER Member Group of the Greens/European Free Alliance Germany Ökologisch-Demokratische Partei Jerzy BUZEK Member Group of the European People's Party (Christian Democrats) Poland Platforma Obywatelska 30/09/2021 1 Aymeric CHAUPRADE Member Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy Group France Les Français Libres Javier COUSO PERMUY Member Confederal Group of the European United Left - Nordic Green Left Spain Independiente Arnaud DANJEAN Member Group of the European People's Party -

State of Populism in Europe

2018 State of Populism in Europe The past few years have seen a surge in the public support of populist, Eurosceptical and radical parties throughout almost the entire European Union. In several countries, their popularity matches or even exceeds the level of public support of the centre-left. Even though the centre-left parties, think tanks and researchers are aware of this challenge, there is still more OF POPULISM IN EUROPE – 2018 STATE that could be done in this fi eld. There is occasional research on individual populist parties in some countries, but there is no regular overview – updated every year – how the popularity of populist parties changes in the EU Member States, where new parties appear and old ones disappear. That is the reason why FEPS and Policy Solutions have launched this series of yearbooks, entitled “State of Populism in Europe”. *** FEPS is the fi rst progressive political foundation established at the European level. Created in 2007 and co-fi nanced by the European Parliament, it aims at establishing an intellectual crossroad between social democracy and the European project. Policy Solutions is a progressive political research institute based in Budapest. Among the pre-eminent areas of its research are the investigation of how the quality of democracy evolves, the analysis of factors driving populism, and election research. Contributors : Tamás BOROS, Maria FREITAS, Gergely LAKI, Ernst STETTER STATE OF POPULISM Tamás BOROS IN EUROPE Maria FREITAS • This book is edited by FEPS with the fi nancial support of the European -

Independence Movements in the EU? How Separatism Takes Over and Endangers Europe As a Peace Concept 1

3 / 2019 & Sabine Riedel Independence Movements in the EU? How Separatism Takes over and Endangers Europe as a Peace Concept 1 Separatist movements exist worldwide, often due to conflicts over power and resources. If this phe- nomenon also affects the European Union, all politicians should sound the alarm bells. The EU is a peace project based on an ever-closer cooperation between its members. However, regional parties, which are currently striving for independence, seek a conflict, for the central question is not whether the regions have a right to secession, but whether the EU members will recognise them as states. Since a territorial secession violates the constitutional order against the will of the nation states concerned, the circle of supporters is likely to remain small. Therefore, the separatist parties demand majority decisions from supranational bodies. In this way they want to solve another problem, namely that their regions remain in the EU as full members. The pro-European image cultivated by many separatist parties is therefore a strategic calculation for the realisation of their vision of a ‘Europe of all peoples’, by which they mean though ethnic and cultural units and not the national peoples of the EU. This redefinition of the concept of nation, however, endangers member states’ stability and thus European integration. Independence movements are social forces that independence movements. In fact, the 193 mem- want to separate a regional unit from a certain ber states of the United Nations (UN) decide state territory. Scholars speak of separatism, within the international legal framework whether which can have different goals. -

KDE Civics Test Manual

Civics Test and Administration Manual 1 Table of Contents Introduction.............................................................................................................................................................. 3 Statutory Requirements ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Civics Test ............................................................................................................................................................... 3 Test Administration ................................................................................................................................................. 3 Which Grade Takes the Test? .............................................................................................................................. 3 Accommodations ................................................................................................................................................. 4 Implementation Options ...................................................................................................................................... 4 Scoring the Test ....................................................................................................................................................... 5 Recording Results .................................................................................................................................................... 5 Suggested