Chapter 10 • Principles of Conserving the Arctic's Biodiversity

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ARTHROPOD COMMUNITIES and PASSERINE DIET: EFFECTS of SHRUB EXPANSION in WESTERN ALASKA by Molly Tankersley Mcdermott, B.A./B.S

Arthropod communities and passerine diet: effects of shrub expansion in Western Alaska Item Type Thesis Authors McDermott, Molly Tankersley Download date 26/09/2021 06:13:39 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/11122/7893 ARTHROPOD COMMUNITIES AND PASSERINE DIET: EFFECTS OF SHRUB EXPANSION IN WESTERN ALASKA By Molly Tankersley McDermott, B.A./B.S. A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Science in Biological Sciences University of Alaska Fairbanks August 2017 APPROVED: Pat Doak, Committee Chair Greg Breed, Committee Member Colleen Handel, Committee Member Christa Mulder, Committee Member Kris Hundertmark, Chair Department o f Biology and Wildlife Paul Layer, Dean College o f Natural Science and Mathematics Michael Castellini, Dean of the Graduate School ABSTRACT Across the Arctic, taller woody shrubs, particularly willow (Salix spp.), birch (Betula spp.), and alder (Alnus spp.), have been expanding rapidly onto tundra. Changes in vegetation structure can alter the physical habitat structure, thermal environment, and food available to arthropods, which play an important role in the structure and functioning of Arctic ecosystems. Not only do they provide key ecosystem services such as pollination and nutrient cycling, they are an essential food source for migratory birds. In this study I examined the relationships between the abundance, diversity, and community composition of arthropods and the height and cover of several shrub species across a tundra-shrub gradient in northwestern Alaska. To characterize nestling diet of common passerines that occupy this gradient, I used next-generation sequencing of fecal matter. Willow cover was strongly and consistently associated with abundance and biomass of arthropods and significant shifts in arthropod community composition and diversity. -

Willows of Interior Alaska

1 Willows of Interior Alaska Dominique M. Collet US Fish and Wildlife Service 2004 2 Willows of Interior Alaska Acknowledgements The development of this willow guide has been made possible thanks to funding from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service- Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge - order 70181-12-M692. Funding for printing was made available through a collaborative partnership of Natural Resources, U.S. Army Alaska, Department of Defense; Pacific North- west Research Station, U.S. Forest Service, Department of Agriculture; National Park Service, and Fairbanks Fish and Wildlife Field Office, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Department of the Interior; and Bonanza Creek Long Term Ecological Research Program, University of Alaska Fairbanks. The data for the distribution maps were provided by George Argus, Al Batten, Garry Davies, Rob deVelice, and Carolyn Parker. Carol Griswold, George Argus, Les Viereck and Delia Person provided much improvement to the manuscript by their careful editing and suggestions. I want to thank Delia Person, of the Yukon Flats National Wildlife Refuge, for initiating and following through with the development and printing of this guide. Most of all, I am especially grateful to Pamela Houston whose support made the writing of this guide possible. Any errors or omissions are solely the responsibility of the author. Disclaimer This publication is designed to provide accurate information on willows from interior Alaska. If expert knowledge is required, services of an experienced botanist should be sought. Contents -

Exobasidium Darwinii, a New Hawaiian Species Infecting Endemic Vaccinium Reticulatum in Haleakala National Park

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Mycol Progress (2012) 11:361–371 DOI 10.1007/s11557-011-0751-4 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Exobasidium darwinii, a new Hawaiian species infecting endemic Vaccinium reticulatum in Haleakala National Park Marcin Piątek & Matthias Lutz & Patti Welton Received: 4 November 2010 /Revised: 26 February 2011 /Accepted: 2 March 2011 /Published online: 8 April 2011 # The Author(s) 2011. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Hawaii is one of the most isolated archipelagos Exobasidium darwinii is proposed for this novel taxon. This in the world, situated about 4,000 km from the nearest species is characterized among others by the production of continent, and never connected with continental land peculiar witches’ brooms with bright red leaves on the masses. Two Hawaiian endemic blueberries, Vaccinium infected branches of Vaccinium reticulatum. Relevant char- calycinum and V. reticulatum, are infected by Exobasidium acters of Exobasidium darwinii are described and illustrated, species previously recognized as Exobasidium vaccinii. additionally phylogenetic relationships of the new species are However, because of the high host-specificity of Exobasidium, discussed. it seems unlikely that the species infecting Vaccinium calycinum and V. reticulatum belongs to Exobasidium Keywords Exobasidiomycetes . ITS . LSU . vaccinii, which in the current circumscription is restricted to Molecular phylogeny. Ustilaginomycotina -

Folsomia Candida and the Results of a Ringtest

Toxicity testing with the collembolans Folsomia fimetaria and Folsomia candida and the results of a ringtest P.H. Krogh DMU/AU, Denmark Department of Terrestrial Ecology With contributions from: Mónica João de Barros Amorim, Pilar Andrés, Gabor Bakonyi, Kristin Becker van Slooten, Xavier Domene, Ine Geujin, Nobuhiro Kaneko, Silvio Knäbe, Vladimír Kocí, Jan Lana, Thomas Moser, Juliska Princz, Maike Schaefer, Janeck J. Scott-Fordsmand, Hege Stubberud, Berndt-Michael Wilke August 2008 1 Contents 1 PREFACE 3 2 BIOLOGY AND ECOTOXICOLOGY OF F. FIMETARIA AND F. CANDIDA 4 2.1 INTRODUCTION TO F. FIMETARIA AND F. CANDIDA 4 2.2 COMPARISON OF THE TWO SPECIES 6 2.3 GENETIC VARIABILITY 7 2.4 ALTERNATIVE COLLEMBOLAN TEST SPECIES 8 2.5 DIFFERENCES IN SUSCEPTIBILITY OF THE TWO SPECIES 8 2.6 VARIABILITY IN REPRODUCTION RATES 8 3 TESTING RESULTS OBTAINED AT NERI, 1994 TO 1999 10 3.1 INTRODUCTION 10 3.2 PERFORMANCE 10 3.3 INFLUENCE OF SOIL TYPE 10 3.4 CONCLUSION 11 4 RINGTEST RESULTS 13 4.1 TEST GUIDELINE 13 4.2 PARTICIPANTS 13 4.3 MODEL CHEMICALS 14 4.4 RANGE FINDING 14 4.5 STATISTICAL ANALYSIS 14 4.6 EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN 15 4.7 TEST CONDITIONS 15 4.8 CONTROL MORTALITY 15 4.9 CONTROL REPRODUCTION 16 4.10 VARIABILITY OF TESTING RESULTS 17 4.11 CONCLUSION 18 5 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 27 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 29 7 REFERENCES 30 ANNEX 1 PARTICIPANTS 36 ANNEX 2 LABORATORY CODE 38 ANNEX 3 BIBLIOMETRIC STATISTICS 39 ANNEX 4 INTRALABORATORY VARIABILITY 40 ANNEX 5 CONTROL MORTALITY AND REPRODUCTION 42 ANNEX 6 DRAFT TEST GUIDELINE 44 2 1 Preface Collembolans have been used for ecotoxicological testing for about 4 decades now but they have not yet had the privilege to enter into the OECD test guideline programme. -

FOH Newsletter 2012

FRIENDS Of The University Of Montana HERBARIUM Spring 2012 ....Bruce McCune MORE THAN VASCULAR AT MONTU By Andrea Pipp While perusing the vascular plant, moss, and lichen were the ecological relatives of mosses and incorporated specimens at MONTU you might see the name of Bruce them into his work. He relied on Mason Hale’s first edi- McCune. During his years at UM (1971-1979) Bruce con- tion of How to Know the Lichens and a long paper with tributed mounts of 62 vascular plant species and a larger keys titled “Lichens of the State of Washington” by Grace number of moss and lichen vouchers to the herbarium. Howard. He soon realized Hale’s book was very biased Bruce came to Missoula from the Midwest. Having toward eastern species, for even the most conspicuous grown up in Cincinnati and after completing his freshman lichens found on Mt. Sentinel weren’t in the book. Later year at Lawrence University in Appleton, Wisconsin, he discovered that Howard’s key contained as much mis- Bruce attended a wilderness botany class in northern Min- (Continued on page 7) nesota. There in the moss-carpeted forests he became quite interested in mosses and, in his words, was swept away by a remarkable young lady (Patricia Muir). Eager to escape the industrial winter of Appleton, Bruce fol- lowed Patricia to the University of Montana. That was 1971. The ‘new’ library was under construction, Hitch- cock and Cronquist, as a book, did not exist, and Botany stood on its own – a vibrant, active department, firmly ensconced in its own building. -

A Phylogenetic Overview of the Antrodia Clade (Basidiomycota, Polyporales)

Mycologia, 105(6), 2013, pp. 1391–1411. DOI: 10.3852/13-051 # 2013 by The Mycological Society of America, Lawrence, KS 66044-8897 A phylogenetic overview of the antrodia clade (Basidiomycota, Polyporales) Beatriz Ortiz-Santana1 phylogenetic studies also have recognized the genera Daniel L. Lindner Amylocystis, Dacryobolus, Melanoporia, Pycnoporellus, US Forest Service, Northern Research Station, Center for Sarcoporia and Wolfiporia as part of the antrodia clade Forest Mycology Research, One Gifford Pinchot Drive, (SY Kim and Jung 2000, 2001; Binder and Hibbett Madison, Wisconsin 53726 2002; Hibbett and Binder 2002; SY Kim et al. 2003; Otto Miettinen Binder et al. 2005), while the genera Antrodia, Botanical Museum, University of Helsinki, PO Box 7, Daedalea, Fomitopsis, Laetiporus and Sparassis have 00014, Helsinki, Finland received attention in regard to species delimitation (SY Kim et al. 2001, 2003; KM Kim et al. 2005, 2007; Alfredo Justo Desjardin et al. 2004; Wang et al. 2004; Wu et al. 2004; David S. Hibbett Dai et al. 2006; Blanco-Dios et al. 2006; Chiu 2007; Clark University, Biology Department, 950 Main Street, Worcester, Massachusetts 01610 Lindner and Banik 2008; Yu et al. 2010; Banik et al. 2010, 2012; Garcia-Sandoval et al. 2011; Lindner et al. 2011; Rajchenberg et al. 2011; Zhou and Wei 2012; Abstract: Phylogenetic relationships among mem- Bernicchia et al. 2012; Spirin et al. 2012, 2013). These bers of the antrodia clade were investigated with studies also established that some of the genera are molecular data from two nuclear ribosomal DNA not monophyletic and several modifications have regions, LSU and ITS. A total of 123 species been proposed: the segregation of Antrodia s.l. -

Blister Blight Disease of Tea: an Enigma Chayanika Chaliha and Eeshan Kalita

Chapter Blister Blight Disease of Tea: An Enigma Chayanika Chaliha and Eeshan Kalita Abstract Tea is one of the most popular beverages consumed across the world and is also considered a major cash crop in countries with a moderately hot and humid climate. Tea is produced from the leaves of woody, perennial, and monoculture crop tea plants. The tea leaves being the source of production the foliar diseases which may be caused by a variety of bacteria, fungi, and other pests have serious impacts on production. The blis- ter blight disease is one such serious foliar tea disease caused by the obligate biotrophic fungus Exobasidium vexans. E. vexans, belonging to the phylum basidiomycete primarily infects the young succulent harvestable tea leaves and results in ~40% yield crop loss. It reportedly alters the critical biochemical characteristics of tea such as catechin, flavo- noid, phenol, as well as the aroma in severely affected plants. The disease is managed, so far, by administering high doses of copper-based chemical fungicides. Although alternate approaches such as the use of biocontrol agents, biotic and abiotic elicitors for inducing systemic acquired resistance, and transgenic resistant varieties have been tested, they are far from being adopted worldwide. As the research on blister blight disease is chiefly focussed towards the evaluation of defense responses in tea plants, during infection very little is yet known about the pathogenesis and the factors contrib- uting to the disease. The purpose of this chapter is to explore blister blight disease and to highlight the current challenges involved in understanding the pathogen and patho- genic mechanism that could significantly contribute to better disease management. -

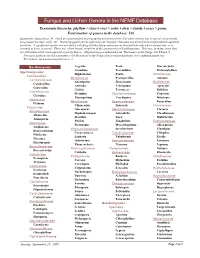

9B Taxonomy to Genus

Fungus and Lichen Genera in the NEMF Database Taxonomic hierarchy: phyllum > class (-etes) > order (-ales) > family (-ceae) > genus. Total number of genera in the database: 526 Anamorphic fungi (see p. 4), which are disseminated by propagules not formed from cells where meiosis has occurred, are presently not grouped by class, order, etc. Most propagules can be referred to as "conidia," but some are derived from unspecialized vegetative mycelium. A significant number are correlated with fungal states that produce spores derived from cells where meiosis has, or is assumed to have, occurred. These are, where known, members of the ascomycetes or basidiomycetes. However, in many cases, they are still undescribed, unrecognized or poorly known. (Explanation paraphrased from "Dictionary of the Fungi, 9th Edition.") Principal authority for this taxonomy is the Dictionary of the Fungi and its online database, www.indexfungorum.org. For lichens, see Lecanoromycetes on p. 3. Basidiomycota Aegerita Poria Macrolepiota Grandinia Poronidulus Melanophyllum Agaricomycetes Hyphoderma Postia Amanitaceae Cantharellales Meripilaceae Pycnoporellus Amanita Cantharellaceae Abortiporus Skeletocutis Bolbitiaceae Cantharellus Antrodia Trichaptum Agrocybe Craterellus Grifola Tyromyces Bolbitius Clavulinaceae Meripilus Sistotremataceae Conocybe Clavulina Physisporinus Trechispora Hebeloma Hydnaceae Meruliaceae Sparassidaceae Panaeolina Hydnum Climacodon Sparassis Clavariaceae Polyporales Gloeoporus Steccherinaceae Clavaria Albatrellaceae Hyphodermopsis Antrodiella -

Collembolans Folsomia Fimetaria and Folsomia Candida and the Results of a Ringtest

Toxicity testing with the collembolans Folsomia fimetaria and Folsomia candida and the results of a ringtest Paul Henning Krogh Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser Aarhus Universitet Environmental Project No. 1256 2009 Miljøprojekt The Danish Environmental Protection Agency will, when opportunity offers, publish reports and contributions relating to environmental research and development projects financed via the Danish EPA. Please note that publication does not signify that the contents of the reports necessarily reflect the views of the Danish EPA. The reports are, however, published because the Danish EPA finds that the studies represent a valuable contribution to the debate on environmental policy in Denmark. Contents 1 PREFACE 5 2 BIOLOGY AND ECOTOXICOLOGY OF F. FIMETARIA AND F. CANDIDA 7 2.1 INTRODUCTION TO F. FIMETARIA AND F. CANDIDA 7 2.2 COMPARISON OF THE TWO SPECIES 9 2.3 GENETIC VARIABILITY 10 2.4 ALTERNATIVE COLLEMBOLAN TEST SPECIES 11 2.5 DIFFERENCES IN SUSCEPTIBILITY OF THE TWO SPECIES 11 2.6 VARIABILITY IN REPRODUCTION RATES 11 3 TESTING RESULTS OBTAINED AT NERI, 1994 TO 1999 13 3.1 INTRODUCTION 13 3.2 PERFORMANCE 13 3.3 INFLUENCE OF SOIL TYPE 13 3.4 CONCLUSION 14 4 RINGTEST RESULTS 17 4.1 TEST GUIDELINE 17 4.2 PARTICIPANTS 18 4.3 MODEL CHEMICALS 18 4.4 RANGE FINDING 18 4.5 STATISTICAL ANALYSIS 18 4.6 EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN 19 4.7 TEST CONDITIONS 19 4.8 CONTROL MORTALITY 20 4.9 CONTROL REPRODUCTION 20 4.10 VARIABILITY OF TESTING RESULTS 21 4.11 CONCLUSION 22 5 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 31 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 33 REFERENCES 35 3 4 1 Preface Collembolans have been used for ecotoxicological testing for about four decades now but they have not yet had the privilege to enter into the OECD test guideline programme. -

Multigeneration Exposure of the Springtail Folsomia Candida to Phenanthrene: from Dose-Response Relationships to Threshold Concentrations

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Multigeneration exposure of the springtail Folsomia candida to phenanthrene: From dose-response relationships to threshold concentrations Leon Paumen, M.; Steenbergen, E.; Kraak, M.H.S.; van Straalen, N.M.; van Gestel, C.A.M. DOI 10.1021/es8007744 Publication date 2008 Document Version Final published version Published in Environmental Science and Technology Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Leon Paumen, M., Steenbergen, E., Kraak, M. H. S., van Straalen, N. M., & van Gestel, C. A. M. (2008). Multigeneration exposure of the springtail Folsomia candida to phenanthrene: From dose-response relationships to threshold concentrations. Environmental Science and Technology, 42(18), 6985-6990. https://doi.org/10.1021/es8007744 General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 Environ. -

Responses of Invertebrates to Temperature and Water Stress A

Author's Accepted Manuscript Responses of invertebrates to temperature and water stress: A polar perspective M.J. Everatt, P. Convey, J.S. Bale, M.R. Worland, S.A.L. Hayward www.elsevier.com/locate/jtherbio PII: S0306-4565(14)00071-0 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jtherbio.2014.05.004 Reference: TB1522 To appear in: Journal of Thermal Biology Received date: 21 August 2013 Revised date: 22 January 2014 Accepted date: 22 January 2014 Cite this article as: M.J. Everatt, P. Convey, J.S. Bale, M.R. Worland, S.A.L. Hayward, Responses of invertebrates to temperature and water stress: A polar perspective, Journal of Thermal Biology, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jther- bio.2014.05.004 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting galley proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain. 1 Responses of invertebrates to temperature and water 2 stress: A polar perspective 3 M. J. Everatta, P. Conveyb, c, d, J. S. Balea, M. R. Worlandb and S. A. L. 4 Haywarda* a 5 School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston, Birmingham B15 2TT, UK b 6 British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, High Cross, Madingley Road, 7 Cambridge, CB3 0ET, UK 8 cNational Antarctic Research Center, IPS Building, University Malaya, 50603 Kuala Lumpur, 9 Malaysia 10 dGateway Antarctica, University of Canterbury, Private Bag 4800, Christchurch 8140, New Zealand 11 12 *Corresponding author. -

Ten Principles for Conservation Translocations of Threatened Wood- Inhabiting Fungi

Ten principles for conservation translocations of threatened wood- inhabiting fungi Jenni Nordén 1, Nerea Abrego 2, Lynne Boddy 3, Claus Bässler 4,5 , Anders Dahlberg 6, Panu Halme 7,8 , Maria Hällfors 9, Sundy Maurice 10 , Audrius Menkis 6, Otto Miettinen 11 , Raisa Mäkipää 12 , Otso Ovaskainen 9,13 , Reijo Penttilä 12 , Sonja Saine 9, Tord Snäll 14 , Kaisa Junninen 15,16 1Norwegian Institute for Nature Research, Gaustadalléen 21, NO-0349 Oslo, Norway. 2Dept of Agricultural Sciences, P.O. Box 27, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland. 3Cardiff School of Biosciences, Sir Martin Evans Building, Museum Avenue, Cardiff CF10 3AX, UK 4Bavarian Forest National Park, D-94481 Grafenau, Germany. 5Technical University of Munich, Chair for Terrestrial Ecology, D-85354 Freising, Germany. 6Department of Forest Mycology and Plant Pathology, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, P.O.Box 7026, 750 07 Uppsala, Sweden. 7Department of Biological and Environmental Science, P.O. Box 35, FI-40014 University of Jyväskylä, Finland. 8School of Resource Wisdom, P.O. Box 35, FI-40014 University of Jyväskylä, Finland. 9Organismal and Evolutionary Biology Research Programme, P.O. Box 65, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland. 10 Section for Genetics and Evolutionary Biology, University of Oslo, Blindernveien 31, 0316 Oslo, Norway. 11 Finnish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 7, FI-00014 University of Helsinki, Finland. 12 Natural Resources Institute Finland (Luke), Latokartanonkaari 9, FI-00790 Helsinki, Finland. 13 Centre for Biodiversity Dynamics, Department of Biology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, N-7491 Trondheim, Norway. 14 Artdatabanken, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, P.O. Box 7007, SE-75007 Uppsala, Sweden.