Belarus in Maps.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lute Revival in Pinsk

CULTURE The Minsk Times Thursday, August 29, 2013 9 Film events developed Lute revival in Pinsk near Smorgon Unique Pinsk master restores ancient musical instruments while Brest actress Yanina Malinchik to play a leading role in Russian performing medieval music all over Brest Region filmDeath Battalion Igor Ugolnikov, the screenwriter and producer, tells us, “The fact that an actress from Brest was chosen for this role shows the special connec- tion with our last film:Brest Fortress. She proved her talent and character during film tests.” Death Battalion will be the larg- est Russian film project devoted to the First World War, being filmed with support from the Russian Min- istry of Culture. It is to provide 50 million Russian Roubles of the 250 million total budget. The film tells of a women’s de- tachment, created in St. Petersburg at the order of the 1917 provisional government, to raise the fighting spirit of the army. Events are being filmed near Smorgon, where this fe- male battalion fought heroically. Shooting begins on 31st August, with the premiere scheduled for 1st August, 2014, coinciding with the Me- morial Day for all those soldiers who died during the First World War. Experimental theatre scene BELTA By Lyudmila Ivanova Yury Dubnovitsky shares his love of ancient instrument with pupils Play by daughter of Charlie By Yuri Chernyakevich lute was made and, since then, Yuri lute as a promising instrument.” Mr. familiar with music will understand Chaplin being staged in Minsk has been producing new instruments. Dubnovitsky teaches pupils at the lo- that it’s a true challenge to learn to from 28th September to 21st Pinsk’s residents are now able to His work has made him well-known cal musical school, making them tune play the lute,” explains Mr. -

The Death Penalty in Belarus

Part 1. Histor ical Overview The Death Penalty in Belarus Vilnius 2016 1 The Death Penalty in Belarus The documentary book, “The Death Penalty in Belarus”, was prepared in the framework of the campaign, “Human Rights Defenders against the Death Penalty in Belarus”. The book contains information on the death penalty in Belarus from 1998 to 2016, as it was in 1998 when the mother of Ivan Famin, a man who was executed for someone else’s crimes, appealed to the Human Rights Center “Viasna”. Among the exclusive materials presented in this publication there is the historical review, “A History of The Death Penalty in Belarus”, prepared by Dzianis Martsinovich, and a large interview with a former head of remand prison No. 1 in Minsk, Aleh Alkayeu, under whose leadership about 150 executions were performed. This book is designed not only for human rights activists, but also for students and teachers of jurisprudence, and wide public. 2 Part 1. Histor ical Overview Life and Death The Death penalty. These words evoke different feelings and ideas in different people, including fair punishment, cruelty and callousness of the state, the cold steel of the headsman’s axe, civilized barbarism, pistol shots, horror and despair, revolutionary expediency, the guillotine with a basket where the severed heads roll, and many other things. Man has invented thousands of ways to kill his fellows, and his bizarre fantasy with the methods of execution is boundless. People even seem to show more humanness and rationalism in killing animals. After all, animals often kill one another. A well-known Belarusian artist Lionik Tarasevich grows hundreds of thoroughbred hens and roosters on his farm in the village of Validy in the Białystok district. -

Tver If You Are on the Group Flight, You Will Be Met at the Airport by Your RLUS Representatives

Your Arrival in Tver If you are on the group flight, you will be met at the airport by your RLUS representatives. There may be many students coming through all at once, so please be patient. You will then be taken to Tver in a minibus provided by the university, and will be taken to your accommodation. The journey to Tver is relatively short - approximately 2 hours and 30 minutes depending on traffic. If you are not travelling with the RLUS group flight, you will be expected to make your own way to Tver and to your accommodation. We will provide you with your address and transport information in this case. Public transport from the airport is reasonably-priced and easily navigable. All Moscow airports have a train service to the city, called Aeroexpress. The train costs 500 roubles and takes approximately 45 minutes to get to the city, depending on which airport you arrive at. When you arrive at the station, follow the signs to the metro, which is characterised by a big red M. You can buy tickets from the ticket office inside. Once you arrive into central Moscow, you can take an elektrichka train to Tver – these are small, local trains for which you do not need to buy a ticket in advance. You’d better take a local high-speed train called “Lastochka” Moscow – Tver. It takes 1 hour and 40 min. to get to Tver. It costs 535 roubles. You should buy a ticket at a railway station cash desk or from machines at the train station. -

Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1St Edition)

R O C K i n t h e R E S E R V A T I O N Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt Rock in the Reservation: Songs from the Leningrad Rock Club 1981-86 (1st edition). (text, 2004) Yngvar B. Steinholt. New York and Bergen, Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. viii + 230 pages + 14 photo pages. Delivered in pdf format for printing in March 2005. ISBN 0-9701684-3-8 Yngvar Bordewich Steinholt (b. 1969) currently teaches Russian Cultural History at the Department of Russian Studies, Bergen University (http://www.hf.uib.no/i/russisk/steinholt). The text is a revised and corrected version of the identically entitled doctoral thesis, publicly defended on 12. November 2004 at the Humanistics Faculty, Bergen University, in partial fulfilment of the Doctor Artium degree. Opponents were Associate Professor Finn Sivert Nielsen, Institute of Anthropology, Copenhagen University, and Professor Stan Hawkins, Institute of Musicology, Oslo University. The pagination, numbering, format, size, and page layout of the original thesis do not correspond to the present edition. Photographs by Andrei ‘Villi’ Usov ( A. Usov) are used with kind permission. Cover illustrations by Nikolai Kopeikin were made exclusively for RiR. Published by Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, Inc. 401 West End Avenue # 3B New York, NY 10024 USA Preface i Acknowledgements This study has been completed with the generous financial support of The Research Council of Norway (Norges Forskningsråd). It was conducted at the Department of Russian Studies in the friendly atmosphere of the Institute of Classical Philology, Religion and Russian Studies (IKRR), Bergen University. -

Russia Train E-Tickets

Features - Eligibility - Validity - Discounts - Conditions of use - More - Maps Russia Train E-tickets Russia Train E-Tickets Travel by train between popular Russian destinations such as: Moscow, St Petersburg, Kazan, Volgograd, Nizhni Novgorod and Yekaterinburg. As Russia spans 3 continents and shares borders with 14 neighbouring countries, travelers will be sure to appreciate its cultural diversity and changing landscapes. Pre-booking time: 45 days Features: Travel on the Russian railways using e-tickets. Note that depending on the ticket your purchase, the issuing method will vary. Here are the two options: o Print at home e-registrations Appears as Russian Railways E-Registration Ticket and Reservation Tickets on some routes are exclusively available as print-at-home e-tickets. This requires the customers to print the purchased tickets and bring them at the station. o Print at the Station e-tickets Appears as Russian Railways E-ticket and Reservation Some tickets can only be redeemed from the ticket collection machines in a select list of train stations. The customer must use the booking confirmation number to print the ticket at the station. Book short and long distance domestic rail routes including sleeping cabins. Moscow features 9 major train stations and there are 5 major stations in St-Petersburg. See ‘more’ for a table of train destinations, metros & airports for each station. Tickets are available in both Standard and First Class. You can book 1st, 2nd and 3rd class cabins with sleeping accommodations. Click here for the complete product guide. Eligibility: For sale outside of Russia and Russian citizens and residents are not eligible. -

Byelorussian Chronicle 1967 I. the International Scene *

370 THE JOURNAL OF BYELORUSSIAN STUDIES Byelorussian Chronicle 1967 I. The International Scene I. GENERAL In May the Byelorussian delegate * to the United Nations L. Klackoŭ A Byelorussian delegation also took spoke at the General Assembly of the part in the sessions of the European need to grant immediate indepen Economic Commission of the United dence to South-West Africa. * Nations in Geneva. * In June a delegation, headed by A. Šeldaŭ, took part in the 51st session of On the 24th June the head of the the International Labour Organisation delegation to the United Nations A. in Geneva. Later in the year the Perm Hurynovič spoke at the General Assem anent Parliamentary Commission for bly in support of the Arab states in the Foreign Affairs (chairman L. Klackoŭ) Arab-Israeli armed conflict. He spoke recommended the Byelorussian Parl again in October in defence of the iament to ratify the ILO convention's economic interests of the nations resolution concerning the leisure time which had recently attained indepen of industrial workers. dence. II. INTERNATIONAL CULTURAL EXCHANGES T h e U n i t e d N a t i o n s Soviet pavillion. The highlight of the day was a concert given by the famous From November to the end of Byelorussian State Folk Instruments December an exhibition of Byelorus Orchestra under the direction of sian books was held in the United professor I. Žynovič, the Female Folk Nations Library in New York. Song Quartet, the singers Tamara * Šymko, Tamara Nižnikava, Arkadź Saŭčanka, Viktar Vujacič, the ballet A r m e n i a dancers L. -

Protests in Belarus (1994-2011) .Pdf

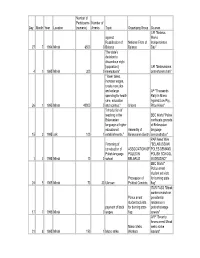

Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources UPI "Belarus against Marks Russification of National Front of Independence 27 7 1994 Minsk 6500 0 Belarus Belarus Day" "the state's decision to discontinue eight [opposition] UPI "Belarussians 4 1 1995 Minsk 300 0 newspapers" protest press ban" " lower taxes, increase wages, create new jobs and enlarge AP "Thousands spending for health Rally In Minsk care, education Against Low Pay, 26 1 1995 Minsk 40000 0 and science." Unions Price Hikes" "introduction of teaching in the BBC World "Police Belarussian confiscate grenade language at higher at Belarussian educational Assembly of language 15 2 1995 unk 100 1 establishments," Belarussian Gentry demonstration" PAP News Wire Financing of "BELARUSSIAN construction of ASSOCIATION OF POLES DEMAND Polish language POLES IN POLISH SCHOOL 1 3 1995 Minsk 10 0 school BELARUS IN GRODNO" BBC World " Police arrest student activists Procession of for burning state 24 5 1995 Minsk 70 30 Uknown Political Convicts flag" ITAR-TASS "Minsk workers march on Police arrest presidential student activists residence in payment of back for burning state protest at wage 17 7 1995 Minsk . 0 wages flag arrears" AFP "Security forces arrest Minsk Minsk Metro metro strike 21 8 1995 Minsk 150 1 Metro strike Workers leaders" Number of Participants Number of Day Month Year Location (numeric) Arrests Topic Organizing Group Sources Interfax "Belarusian Popular Front Reconsideration of protests against oil oil agreement with -

According to Chaim Weizmann's

Motal Pol. Motol, Bel. Моталь, [We] had our own house – one storey, with seven rooms and a kitchen some acres of land, chickens, two cows, a vegetable garden, a few – מאָטעלע .Yid fruit trees. So we had a supply of milk, and sometimes butter; we had fruit and vegetables in season; we had enough bread – which my mother baked herself; we had fish, and we had meat once a week – on the Sabbath. And there was always plenty of fresh air. Chaim Weizmann, Trial and Error. The Autobiography, Philadelphia 1949 Hebrew greeting ¶ Motal, the into the Slonim Province, then into the birthplace and childhood home of Lithuania Governorate, and from 1801, it Chaim Weizmann, the first president was made part of the Grodno Province of of Israel, is probably the only town in the Russian Empire. Belarus that has a sign with its name in Hebrew posted by the road leading out of The Jews of Motal ¶ In 1562, town. ¶ The earliest written mention of “a Jewish landlord and tax collector from Motal is found in the documents of the Kobryn Favish Yeskovich,” who leased Lithuanian Metrica from 1422, where the right to collect taxes on merchandise, it was referred to as a private estate in complained to Savostian Druzhylovitski the Principality of Pinsk. In 1520, it was that the ruler of the district did not allow the property of Prince Fyodor Ivanovich him to collect taxes in his town of Motal Yaroslavich, who later donated it to the and in the neighbouring villages. This Orthodox Church of the Assumption of document suggests that Jews collecting the Blessed Virgin Mary in Leszno. -

Of Vilna (Vilnius)’, Polish Spelling Wilenski

III Hillel Cohen, furrier II Joseph Jacob Cohen, b. 1898/9, shopfitter, d. 4 Aug 1948 Bury New Road (aged 49), bur. Rainsough JC, Prestwich (block J, no. 58) + Besty Portner, b. 1902 Bury New Road, Manchester, m. 14 Jun 1927 South Broughton Synagogue, Manchester, d. ?? I Muriel R Cohen, b. Q4 1930 Manchester North + Eric Vernon (born Valensky), m. Q1 1951 Central Synagogue, Manchester, bur. 2000 Agecroft Jewish Cemetery Vilenski (Виленскый) = Russian for ‘of Vilna (Vilnius)’, Polish spelling Wilenski IV Marks Vilensky/Vellensky/Villensky, b. 1843 Poland, tailor, d. 19 Feb 1920 Prestwich (aged 70), bur. Crumpsall Jewish Cemetery + Betsy (Beyla or Brayne) Markus, b. 1841 Poland, m. 1861 Poland, d. 10 Apr 1925 Manchester (aged 70), bur. Crumpsall Jewish Cemetery III Hyman-Levy Vellensky/Vellansky, b. 1864/6 Poland, tailor, d. May 1927 Salford (aged 59), bur. 27 May 1927 Failsworth (row E, grave no. 25) + Sarah Levy, b. 1868 London, m. 15 Mar 1887 Great Synagogue, Manchester, d. Apr 1929 Salford (aged 58), bur. 4 Apr 1929 Failsworth Jewish Cemetery (row D, grave no. 39) II Philip Vellensky, b. 1887 Manchester II Isaac Vellensky, b. 1889 Manchester II Barnet Vellensky, b. 1891 Manchester II Samuel Vellensky/Valensky/Vernon, b. 1893 Manchester (Q1 Prestwich), waterproof garment maker [poss. b. 26 Feb 1893, d. Q1 1974 Manchester] + Henrietta Brown, m. 19 May 1920 South Broughton Synagogue, waterproof garment maker [poss. b. 15 Feb 1895, d. Q2 1974 Manchester] I Myer Valensky, b. 1921 Manchester I Eric Valensky (later Vernon), b. 6 Jan 1923 Manchester, bur. 2000 Agecroft Jewish Cemetery + Muriel R Cohen, b. -

A Sweet History in Bitter Times: Refining Sugar in the Transnistrian Borderlands (1898-2015)

A SWEET HISTORY IN BITTER TIMES: REFINING SUGAR IN THE TRANSNISTRIAN BORDERLANDS (1898-2015) by Alexandru Lesanu A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy History Committee: ___________________________________________ Director ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Department Chairperson ___________________________________________ Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, College of Humanities and Social Sciences Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA A Sweet History in Bitter Times: Refining Sugar in the Transnistrian Borderlands (1898-2015) A Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at George Mason University by Alexandru Lesanu Master of Arts Central European University, Budapest, Hungary, 2005 Bachelor of Arts Low Danube University, Galati, Romania, 2003 Director: Steven Barnes, Professor Department of History and Art History Fall Semester 2015 George Mason University Fairfax, VA This work is licensed under a creative commons attribution-noderivs 3.0 unported license. ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A dissertation is a long journey and it cannot be completed without the support of numerous travel companions. I would like to thank Steven Barnes, my dissertation adviser, who shared this journey from its beginning in 2008 until its end in 2015. During the journey, Steve was not only a meticulous adviser but also a valuable travel companion. Thanks to the other two members of my dissertation committee, Mills Kelly and Paula Petrik, for their precious travel advice. Among many movie and book recommendations, Mills suggested that Bridge on the Drina by Ivo Andric would be an inspired reading during my journey. -

8. Regions and Regional Planning

8. REGIONS AND REGIONAL PLANNING Spatial inequalities and regions at a glance The most sparsely populated area is Paliessie, which lies in the south. The only exceptions Whereas landscapes in Belarus change from within this area are the eastern and western gate- north to south (e.g. from the Belarusian Lakeland ways of Brest and Homieĺ, which are the admin- in the north to the Paliessie region in the south), istrative centres of the region. in terms of socio-economic development the Brest, which is the location of the largest country exhibits an east-west gradient as well border crossing in the west, is famous for its as regional differences that reflect centre-pe- fortress. The Bielaviežskaja Pušča National Park riphery disparities. Some of these inequalities near Brest is a World Heritage Nature Reserve. It can be traced back to the period when the coun- received this status as Europe’s largest primeval try’s western regions formed a part of Poland forest. The pride of the park is its population of (Kireenko, E.G. 2003). The east-west dichotomy bison. Brest is also renowned as the site of sever- is also apparent in the more industrialized nature al major historical treaties and events (the Brest of the eastern regions (Ioffe, G. 2004, 2006) and Union of 1596, the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk of 1918, the richer cultural and architectural heritage of the defence of the Brest Fortress in 1941, and the western areas with their more favourable demo- graphics. Nevertheless, these differences are far less profound than those seen in Ukraine. -

Review–Chronicle

REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 Human Rights Center Viasna ReviewChronicle » of the Human Rights Violations in Belarus in 2005 VIASNA « Human Rights Center Minsk 2006 1 REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 » VIASNA « Human Rights Center 2 Human Rights Center Viasna, 2006 REVIEWCHRONICLE of the human rights violations in Belarus in 2005 INTRODUCTION: main trends and generalizations The year of 2005 was marked by a considerable aggravation of the general situation in the field of human rights in Belarus. It was not only political rights » that were violated but social, economic and cultural rights as well. These viola- tions are constant and conditioned by the authoritys voluntary policy, with Lu- kashenka at its head. At the same time, human rights violations are not merely VIASNA a side-effect of the authoritarian state control; they are deliberately used as a « means of eradicating political opponents and creating an atmosphere of intimi- dation in the society. The negative dynamics is characterized by the growth of the number of victims of human rights violations and discrimination. Under these circums- tances, with a high level of latent violations and concealed facts, with great obstacles to human rights activity and overall fear in the society, the growth points to drastic stiffening of the regimes methods. Apart from the growing number of registered violations, one should men- Human Rights Center tion the increase of their new forms, caused in most cases by the development of the state oppressive machine, the expansion of legal restrictions and ad- ministrative control over social life and individuals.