Edinburgh Research Explorer

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Science, Values, and the Novel

Science, Values, & the Novel: an Exercise in Empathy Alan C. Hartford, MD, PhD, FACR Associate Professor of Medicine (Radiation Oncology) Geisel School of Medicine at Dartmouth 2nd Annual Symposium, Arts & Humanities in Medicine 29 January 2021 The Doctor, 1887 Sir Luke Fildes, Tate Gallery, London • “One of the essential qualities of the clinician is interest in humanity, for the secret of the care of the patient is in caring for the patient.” From: Francis W. Peabody, “The Care of the Patient.” JAMA 1927; 88: 877-882. Francis Weld Peabody, MD 1881-1927 Empathy • Empathy: – “the ability to understand and share the feelings of another.” • Cognitive (from: Oxford Languages) • Affective • Somatic • Theory of mind: – “The capacity to identify and understand others’ subjective states is one of the most stunning products of human evolution.” (from: Kidd and Castano, Science 2013) – Definitions are not full agreed upon, but this distinction is: • “Affective” and “Cognitive” empathy are independent from one another. Can one teach empathy? Reading novels? • Literature as a “way of thinking” – “Literature’s problem is that its irreducibility … makes it look unscientific, and by extension, soft.” – For example: “‘To be or not to be’ cannot be reduced to ‘I’m having thoughts of self-harm.’” – “At one and the same time medicine is caught up with the demand for rigor in its pursuit of and assessment of evidence, and with a recognition that there are other ways of doing things … which are important.” (from: Skelton, Thomas, and Macleod, “Teaching literature -

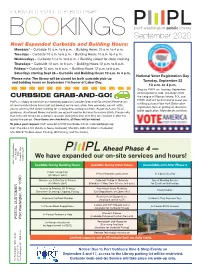

BOOKINGS September 2020 New! Expanded Curbside and Building Hours: Mondays* – Curbside 10 A.M

YOUR MONTHLY GUIDE TO PORT’S LIBRARY BOOKINGS September 2020 New! Expanded Curbside and Building Hours: Mondays* – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Tuesdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Wednesdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building closed for deep cleaning. Thursdays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Fridays – Curbside 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. • Building Hours 12 p.m. to 6 p.m. Saturdays starting Sept 26 – Curbside and Building Hours 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. National Voter Registration Day *Please note: The library will be closed for both curbside pick-up and building hours on September 7 in honor of Labor Day. Tuesday, September 22 10 a.m. to 4 p.m. Stop by PWPL on Tuesday, September 22 to register to vote. Volunteers from CURBSIDE GRAB-AND-GO! the League of Woman Voters, FOL and PWPL staff will be on hand to assist you PWPL is happy to continue our extremely popular Curbside Grab-and-Go service! Reserve any in filling out your New York State voter of your favorite library items (not just books!) online and, when they are ready, we will notify registration form or getting an absentee you to come by the library building for a contactless pickup out front. As per ALA and OCLC ballot application. More details to follow. guidance, all returned library materials are quarantined for 96 hours to ensure safety. -

University of Huddersfield Repository

University of Huddersfield Repository Billam, Alistair It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Original Citation Billam, Alistair (2018) It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema. Masters thesis, University of Huddersfield. This version is available at http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/id/eprint/34583/ The University Repository is a digital collection of the research output of the University, available on Open Access. Copyright and Moral Rights for the items on this site are retained by the individual author and/or other copyright owners. Users may access full items free of charge; copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided: • The authors, title and full bibliographic details is credited in any copy; • A hyperlink and/or URL is included for the original metadata page; and • The content is not changed in any way. For more information, including our policy and submission procedure, please contact the Repository Team at: [email protected]. http://eprints.hud.ac.uk/ Submission in fulfilment of Masters by Research University of Huddersfield 2016 It Always Rains on Sunday: Early Social Realism in Post-War British Cinema Alistair Billam Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 3 Chapter 1: Ealing and post-war British cinema. ................................................................................... 12 Chapter 2: The community and social realism in It Always Rains on Sunday ...................................... 25 Chapter 3: Robert Hamer and It Always Rains on Sunday – the wider context. -

Download the Expanded Digital Edition Here

Spring 1999 December 2002 April 2002 February 2003 May 2003 September 2003 November 2003 October 2004 March 2005 October 2003 November 2007 August 2009 July 2010 April 2012 September 2012 September 2010 April 2011 June 2012 June 2012 November 2012 November 2012 November 2012 January 2013 January 2013 January 2013 I created The Rainbow Orchid because making comics is such hard work that I wanted to write and draw one that I could be absolutely certain at least one person would really like – that person being me. It is steeped in all the things I love. From the adventure stories of H. Rider Haggard, Jules Verne and Arthur Conan Doyle I took the long build-up to a fantastic element, made all the more amazing because the characters are immersed in the ‘real world’ for so much of the story. From the comics medium I dipped my pen into the European tradition of Hergé, Edgar P. Jacobs, Yves Chaland and the descendents of their ligne claire legacy, along with the strong sense of environment – a believable world – from Asterix and Tintin. Yet I wanted characters and a setting that were very strongly British, without being patriotic. Mixed into all this is my fondness for an involving and compelling plot, and artistic influences absorbed from a wealth of comic artists and illustrators, from Kay Neilsen to Bryan Talbot, and a simple love of history and adventure. No zombies, no bikini-clad gun-toting nubiles, and no teeth-gritting ... grittiness. Just a huge slice of pure adventure, made to go with a big mug of tea. -

![1940-08-29, [P ]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5100/1940-08-29-p-805100.webp)

1940-08-29, [P ]

SPECIAL LABOR EDITION THE NEWARK LEADER, THURSDAY, AUGUST 29, 1940 SPECIAL LABOR EDITION family visited Mr. and Mrs. Cary Newark Men Will McKinney Sunday. MIDLAND - AUDITORIUM SHOWS Miss Mary Klingenberg of Unemployment Bureau of Athens visited Mr. and Mrs. Enjoy Sailing Cary McKinney on Sunday after “SOUTH OF PAGO PAGO” noon. Now playing, Thursday to Mrs. Blanche Evans, son Rus Saturday, August 29-31, at the Schooner Trip sell, her daughter Mrs. Violet Great Importance to Workers Midland theatre — a thrilling Brunner, her grandson Llewellyn tropic love drama of the south Jerome Norpell, Wm. M. Ser Courson and Mrs. Nan Minego Of great importance to the days or more. Members of the seas with a stellar cast of play geant, George Pfeffer, John went on a picnic to Baughman’s Welfare of Licking county’s staff also made 1950 calls on ers, enacting a story of thrilling Spencer and Dr. Paul McClure, park Sunday. workers is District Office No. 38, prospective employers, explain adventure. “South of Pago will leave this Friday for Maine, Mrs. Blanche Evans visited Bureau of Unemployment Com ing the service and soliciting op Pago” starring Jon Hall, Fran on a short vacation trip. It is friends in Delaware and Marion pensation, located at 28-30 North enings. ces Farmer, Victor McLagen and their plan to sail on a Small last week. Fourth street. The nine mem One of the most successful em others concerns the strange ad schooner off the coast of Maine, Mr. and Mrs. Earl Gleckler bers of the staff consist of John ployment campaigns conducted ventures of Bucko Larson and and enjoy the fabulous fishing and daughter and Leroy Rowe of Gilbert, manager, and two sen in Newark during the period Ruby Taylor, who undertake an grounds and beautiful scenery Martinsburg road were Sunday ior and two junior interviewers; was the “Clean Up—Give a Job” adventure to the famous pearl along the coast. -

The Client Who Did Too Much

The University of Akron IdeaExchange@UAkron Akron Law Review Akron Law Journals June 2015 The lieC nt Who Did Too Much Nancy B. Rapoport Please take a moment to share how this work helps you through this survey. Your feedback will be important as we plan further development of our repository. Follow this and additional works at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview Part of the Legal Ethics and Professional Responsibility Commons Recommended Citation Rapoport, Nancy B. (2014) "The lC ient Who Did Too Much," Akron Law Review: Vol. 47 : Iss. 1 , Article 6. Available at: http://ideaexchange.uakron.edu/akronlawreview/vol47/iss1/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Akron Law Journals at IdeaExchange@UAkron, the institutional repository of The nivU ersity of Akron in Akron, Ohio, USA. It has been accepted for inclusion in Akron Law Review by an authorized administrator of IdeaExchange@UAkron. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Rapoport: The Client Who Did Too Much ARTICLE 6 RAPOPORT MACRO (DO NOT DELETE) 2/5/2014 2:06 PM THE CLIENT WHO DID TOO MUCH∗ Nancy B. Rapoport∗∗ The whole point of the MacGuffin is that it is irrelevant. In Hitchcock’s own words, the MacGuffin is: the device, the gimmick, if you will, or the papers the spies are after. .[.] The only thing that really matters is that in the picture the plans, documents or secrets must seem to be of vital importance to the characters. To me, the narrator, they’re of no importance whatsoever. -

Boredom Takestoll at Welles Village I Prixeweek Puzzle Today: Win $100

PAGE TWENTY <- EVENING HERALD, Fri., Sept. 7, 1979 Boredom TakesToll at Welles Village I Prixeweek Puzzle Today: Win $100 Hy DAVK I, VVAM,KK village. There are over 300 of them, starting point and perhaps funds for afraid the young'persons will find out vices Bureaus' programs because has found a way to do that yet,” Hoff Unique Music Book Board Approves Hiring Teachers Subpoenaed Chris Evert Stops King this project are next to impossible, Mfriilil Ki'iiorlcr but out of that group eight are giving and will come back to avenge the they do not think they would fit in man explained. Made for Silent Films Of New Science Head For Court Defiance To Reach Open Finals us problems. Two or three of them but there could be other areas such report,” Willett said. with programs. Hoffman said that one of the GLASTONBURY - On any hot, are supplying beer to kids who are as athletic equipment stocked at the Willett said that the major way to "We like rugged things,'- one solutions would be to separate the P age 2 P age 6 P age 6 Page 1 0 humid night in Welles Village, the underaged and I am going to do rental office for sign out use or a curb these problems would be to juvenile said. “We do different kinds scene js the same. Young persons elderly people in the village from the h---------- ---------- ' ■ everything in my power to throw the CETA worker to run various sports provide more recreationai oppor of things than the kinds of things they juveniles. -

Orange County Board of Commissioners Agenda Business

Orange County Board of Commissioners Agenda Business Meeting Note: Background Material December 10, 2019 on all abstracts 7:00 p.m. available in the Southern Human Services Center Clerk’s Office 2501 Homestead Road Chapel Hill, NC 27514 Compliance with the “Americans with Disabilities Act” - Interpreter services and/or special sound equipment are available on request. Call the County Clerk’s Office at (919) 245-2130. If you are disabled and need assistance with reasonable accommodations, contact the ADA Coordinator in the County Manager’s Office at (919) 245-2300 or TDD# 919-644-3045. 1. Additions or Changes to the Agenda PUBLIC CHARGE The Board of Commissioners pledges its respect to all present. The Board asks those attending this meeting to conduct themselves in a respectful, courteous manner toward each other, county staff and the commissioners. At any time should a member of the Board or the public fail to observe this charge, the Chair will take steps to restore order and decorum. Should it become impossible to restore order and continue the meeting, the Chair will recess the meeting until such time that a genuine commitment to this public charge is observed. The BOCC asks that all electronic devices such as cell phones, pagers, and computers should please be turned off or set to silent/vibrate. Please be kind to everyone. Arts Moment – Andrea Selch joined the board of Carolina Wren Press 2001, after the publication of her poetry chapbook, Succory, which was #2 in the Carolina Wren Press poetry chapbook series. She has an MFA from UNC-Greensboro, and a PhD from Duke University, where she taught creative writing from 1999 until 2003. -

Cataleg Definitiu.Pdf

Quan el 1934 Madeleine Carroll va trepitjar per primera vegada la Costa Brava, aquesta actriu anglesa era encara poc coneguda fora de les pantalles britàniques. L’imminent pas cap a Hollywood li va fer encetar una carrera fulgurant impulsada pel treball amb alguns dels més prestigiosos directors del moment: John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, William Dieterle, Cecil B. de Mille… Va ser en aquesta època quan les nostres comarques es van convertir en refugi de l’estrella entre rodatge i rodat- ge, però la tranquil·litat que més anhelava es va veure interrompuda per l’esclat de la Guerra Civil, que la va mantenir allunyada de la seva propietat catalana. En poc temps la mateixa ombra de la guerra s’estendria per tot Europa. Madeleine Carroll no va voler ser una simple espectadora del conflicte i va decidir-se a parti- cipar activament per recuperar la pau i els valors democràtics i es va implicar d’una manera molt personal com a membre de la Creu Roja, per donar suport a les vícti- mes més directes de la guerra, sobretot als nens orfes francesos i als soldats ame- ricans ferits. Ara, aprofitant el centenari del seu naixement i valent-nos d’alguns objectes i docu- ments del llegat de l’actriu, que ella mateixa conservava com els seus records més preuats, us proposem fer un recorregut per descobrir els diferents aspectes de la vida de Madeleine Carroll, des del més glamourós al més compromès. UNA ACTRIU ANGLESA A HOLLYWOOD Poc temps després de descobrir la passió pel teatre a la universitat, Madeleine Carroll (West Bromwich, Birmingham, 1906) que exercia de professora de francès, va viatjar a Londres a estudiar interpretació, obviant l’oposició familiar. -

John Buchan Wrote the Thirty-Nine Steps While He Was Ill in Bed with a Duodenal Ulcer, an Illness Which Remained with Him All His Life

John Buchan wrote The Thirty-Nine Steps while he was ill in bed with a duodenal ulcer, an illness which remained with him all his life. The novel was his first ‘shocker’, as he called it — a story combining personal and political dramas. The novel marked a turning point in Buchan's literary career and introduced his famous adventuring hero, Richard Hannay. He described a ‘shocker’ as an adventure where the events in the story are unlikely and the reader is only just able to believe that they really happened. The Thirty-Nine Steps is one of the earliest examples of the 'man-on-the-run' thriller archetype subsequently adopted by Hollywood as an often-used plot device. In The Thirty-Nine Steps, Buchan holds up Richard Hannay as an example to his readers of an ordinary man who puts his country’s interests before his own safety. The story was a great success with the men in the First World War trenches. One soldier wrote to Buchan, "The story is greatly appreciated in the midst of mud and rain and shells, and all that could make trench life depressing." Richard Hannay continued his adventures in four subsequent books. Two were set during the war when Hannay continued his undercover work against the Germans and their allies The Turks in Greenmantle and Mr Standfast. The other two stories, The Three Hostages and The Island of Sheep were set in the post war period when Hannay's opponents were criminal gangs. There have been several film versions of the book; all depart substantially from the text, for example, by introducing a love interest absent from the original novel. -

Macguffin Film Working Title: Process Junkies

Don’t Get Sued! Th is script is available through the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 licence. As a way of showing thanks, please be aware of the screenwriter’s neurosis. Screenwriters are very particular about how they receive credit, and this script is no exception. While your fi lm project is essentially yours, please adhere to these guidelines when giving screen writing credit. If you use the screenplay with no modifi cations to it, credit me the following way: Screenplay by M. Robert Turnage, 26screenplays.com If you use the screenplay and modify it less than 50%, credit me the following way: Screenplay by M. Robert Turnage, 26screenplays.com and [Your name] If you use the screenplay and modify it between 51 and 90%, credit me the following way: Screenplay by [Your name] and M. Robert Turnage, 26screenplays.com If you use the screenplay and modify it more than 90%, credit me the following way: Original story by M. Robert Turnage, 26screenplays.com And if you just like the 26 Screenplays project or the idea of Creative Commons screenplays, feel free to show your support by adding the following credit to your fi lm: Special thanks to M. Robert Turnage, 26screenplays.com Of course, another way to show appreciation is to include some reference to the 26screenplays.com web site in your fi lm. Th is can happen by having a character wear a 26 Screenplays T-shirt, having the book displayed in the back- ground someplace, or just mention the web site on a monitor somewhere in your project. -

Hitchcock's Screenwriting and Identification

Remaking The 39 Steps Hitchcock’s Screenwriting and Identification Will Bligh May 2018 Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Technology Sydney. This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Certificate of Original Authorship I certify that the work in this thesis has not previously been submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research work and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Signature of Student: Date: 18th May 2018 ii Acknowledgements I would like to thank my principal supervisor, Dr Alex Munt, for his on-going support and commitment to the completion of my research. His passion for film was a constant presence throughout an extended process of developing my academic and creative work. Thanks also to my associate supervisor, Margot Nash, with whom I began this journey when she supervised the first six months of my candidature and helped provide a clear direction for the project. This research is supported by an Australian Government Research Training Program Scholarship. Thanks to Dr Inez Templeton, who edited the dissertation with attention to detail. Lastly, but certainly not least, my wife Esther was a shining light during a process with many ups and downs and provided a turning point in my journey when she helped me find the structure for this thesis.