Cbfim in the Tanami Desert Region of Central Australia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 – 2019 Contents

TOURISM CENTRAL AUSTRALIA STRATEGIC PLAN 2016 – 2019 Contents Introduction from the Chair ..........................................................................3 Our Mission ........................................................................................................4 Our Vision ............................................................................................................4 Our Objectives ...................................................................................................4 Key Challenges ...................................................................................................4 Background .........................................................................................................4 The Facts ..............................................................................................................6 Our Organisation ..............................................................................................8 Our Strengths and Weaknesses ...................................................................8 Our Aspirations ................................................................................................10 Tourism Central Australia - Strategic Focus Areas ...............................11 Improving Visitor Services and Conversion Opportunities ...............11 Strengthening Governance and Planning ..............................................12 Enhancing Membership Services ..............................................................13 Partnering in Product -

Tanami Desert 1

Tanami Desert 1 Tanami Desert 1 (TAN1 – Tanami 1 subregion) GORDON GRAHAM SEPTEMBER 2001 Subregional description and The Continental Stress Class for TAN1 is 5. biodiversity values Known special values in relation to landscape, ecosystem, species and genetic values Description and area There are no known special values within TAN1. Mainly red Quaternary sandplains overlying Permian and Proterozoic strata that are exposed locally as hills and Existing subregional or bioregional plans and/or ranges. The sandplains support mixed shrub steppes of systematic reviews of biodiversity and threats Hakea spp., desert bloodwoods, Acacia spp. and Grevillea spp. over soft spinifex (Triodia pungens) hummock The CTRC report in 1974 (System 7) formed the basis grasslands. Wattle scrub over soft spinifex (T. pungens) of the Department’s publication “Nature Conservation hummock grass communities occur on the ranges. Reserves in the Kimberley” (Burbidge et al. 1991) which Alluvial and lacustrine calcareous deposits occur has itself been incorporated in a Departmental Draft throughout. In the north they are associated with Sturt Regional Management Plan (Portlock et al. 2001). These Creek drainage, and support ribbon grass (Chrysopogon reports were focused on non-production lands and those spp.) and Flinders grass (Iseilema spp.) short-grasslands areas not likely to be prospective for minerals. Action often as savannas with river red gum. The climate is arid statements and strategies in the draft regional tropical with summer rain. Subregional area is 3, 214, management plan do not go to the scale of subregion or 599ha. even bioregion. Dominant land use Apart from specific survey work there has been no systematic review of biodiversity but it is apparent that The dominant land use is (xi) UCL and Crown reserves there are on-going changes to the status of fauna (see Appendix B, key b). -

PRINCESS PARROT Polytelis Alexandrae

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory PRINCESS PARROT Polytelis alexandrae Conservation status Australia: Vulnerable Northern Territory: Vulnerable Princess parrot. ( Kay Kes Description Conservation reserves where reported: The princess parrot is a very distinctive bird The princess parrot is not resident in any which is slim in build, beautifully plumaged conservation reserve in the Northern and has a very long, tapering tail. It is a Territory but it has been observed regularly in medium-sized parrot with total length of 40- and adjacent to Uluru Kata Tjuta National 45 cm and body mass of 90-120 g. The basic Park, and there is at least one record from colour is dull olive-green; paler on the West MacDonnell National Park. underparts. It has a red bill, blue-grey crown, pink chin, throat and foreneck, prominent yellow-green shoulder patches, bluish rump and back, and blue-green uppertail. Distribution This species has a patchy and irregular distribution in arid Australia. In the Northern Territory, it occurs in the southern section of the Tanami Desert south to Angas Downs and Yulara and east to Alice Springs. The exact distribution within this range is not well understood and it is unclear whether the species is resident in the Northern Territory. Few locations exist in the Northern Territory where the species is regularly seen, and even Known locations of the princess parrot. then there may be long intervals (up to 20 years) between records. Most records from = pre 1970; • = post 1970. the MacDonnell Ranges bioregion are during dry periods. For more information visit www.denr.nt.gov.au Ecology • extreme fluctuations in number of mature individuals. -

Northern Territory Government Response to the Joint Standing Committee on Migration – Inquiry Into Migrant Settlement Outcomes

Northern Territory Government Response to the Joint Standing Committee on Migration – Inquiry into Migrant Settlement outcomes. Introduction: The Northern Territory Government is responding to an invitation from the Joint Standing Committee on Migration’s inquiry into migrant settlement outcomes. The Northern Territory Government agencies will continue to support migrants, including humanitarian entrants through health, education, housing and interpreting and translating services and programs. The Northern Territory Government acknowledges the important role all migrants play in our society and recognises the benefits of effective programs and services for enhanced settlement outcomes. The following information provides details on these programs that support the settlement of the Northern Territory’s migrant community. 1. Northern Territory Government support programs for Humanitarian Entrants Department of Health The Northern Territory Primary Health Network was funded by the Department of Health to undertake a review of the Refugee Health Program in the Northern Territory. The review informed strategic planning and development of the Refugee Health Program in the Northern Territory prior to the development of a tender for provision of these services. The primary objectives of the Program were to ensure: increased value for money; culturally safe and appropriate services; greater coordination across all refugee service providers; clinically sound services; improved health literacy for refugees; and flexibility around ebbs and flows -

Aborigines and the Administration of Social Welfate in Central Australia

j8 BURNJNG MT. KETLY: ABORIGTNËS AND']]IIII AD}IINISTRATÏON OF SOCTAL b]ETù-ARE TN CET'ITRAI, AUST'R.ALTA JEFFREY REf D COLLMANN, B '4. M"A. (ECON" ) Department of AnthropologY The UniversitY of Adelaide 23rd I'lay, L979 J- TABLB OF CONTENTS Tit1e page Tabl-e of Contents t Brief Summary l-t Disclaimer ].V Acknov¡Led.gements V Introduction I Chapter I The Policy of "Self-d.etermination" ancl the Fraqmentation of Aboriginal A<lministratjon i,n Cent-ral Austral-ia L4 Chapter 2 Racial Tensic¡n ancl the Politics of Detriba lization 46 Chapter 3 Frirrge-camps and the Development of Abori.ginaI Adrnj-njstr:ation in Central Aust-ralia oa Chapter 4 lr]c¡men, Childrett, and the Siqni.ficance of the Domestic Group to Ur:l¡arr Aborigines in Central Australi a 127 Chap-Ler 5 Men, Vüork, and the Significance of the Cattle Industry to Urban Fr-inge-Cwel-lers in Central Australia l5:6 Chapter 6 Food, Liquor, and Domestic Credit: A Theory of Drinking among Fringe-dwellers i.n Central Austra l.ia I86 Chapter 7 Violenc,e, Debt and the Negotiat-íon cf Exchatrge 21.r Chapter 8 Conclusirln 256 Appendix J. The Strr¡et-,ure alrd Development of the Centl:a1 Ar:stral-ian Cattle Industry 286 Apper-iCix IT l'lork Careers of Mt" Kelly Aclul.ts 307 Bibliography 308 t1 BRIEF SUMMARY This thesis i.s a general analysis of the structure of social relatícnships between Aborigines and whites in Central Australia. Of particular importance .t. tfr. -

Report on the Administration of the Northern Territory for the Year 1939

1940-41 THE PARLIAMENT OF THE COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA. REPORT ON THE ADMINISTRATION OK THE NORTHERN TERRITORY FOR YEAR 1939-40. Presented by Command, 19th March, 1941 ; ordered to be printed, 3rd April, 1941. [Cost of Paper.—Preparation, not given ; 730 copies ; approximate coat of printing and publishing, £32.) Printed and Published for the GOVERNMENT of the COMMONWEALTH OF AUSTRALIA by L. F. JOHNSTON, Commonwealth Government Printer. Canberra. (Printed In Australia.) 3 No. 24.—F.7551.—PRICE 1S. 3D. Digitised by AIATSIS Library 2007 - www.aiatsis.gov.au 17 The following is an analysis of the year's transactions :— £ s. d. Value of estates current 30th June, 1939 .. 3,044 0 5 Receipts as per cash book from 1st July, 1939 to 30th June, 1940 3,614 1 3 Interest on Commonwealth Savings Bank Accounts 40 9 9 6,698 11 5 Disbursements from 1st July, 1939, to 30th June, 1940 £ s. d. Duty, fees and postage 98 3 5 Unclaimed estates paid to Revenue 296 3 8 Claims paid to creditors of Estates 1,076 7 2 Amounts paid to beneficiaries 230 18 4 1,701 12 7 Values of estates current 30th June, 1940 4,996 18 10 Assets as at 30th June, 1940 :— Commonwealth Bank Balance 1,741 9 7 Commonwealth Savings Bank Accounts 3,255 9 3 4,996 18 10 PATROL SERVICE. Both the patrol vessels Kuru amd Larrakia have carried out patrols during the year and very little mechanical trouble was experienced with either of them. Kuru has fulfilled the early promise of useful service by steaming 10,000 miles on her various duties, frequently under most adverse weather conditions. -

Central Australia Regional Plan 2010-2012 2012 - 2010

Department of Health and Families Central Australia Regional Plan 2010-2012 2012 - 2010 www.healthyterritory.nt.gov.au Northern Territory Central Region DARWIN NHULUNBUY KATHERINE TENNANT CREEK Central Australia ALICE SPRINGS 3 Central Australia Regional Plan In 2009, former Chief Executive of the Department of Health and Families (DHF), Dr David Ashbridge, launched the Department of Health and Families Corporate Plan 2009–2012. He presented the Corporate Plan to Department staff, key Government and political representatives, associated non-government organisations, Aboriginal Medical Services and peak bodies. The Central Australia Regional Plan is informed by the Corporate Plan and has brought together program activities that reflect the Department’s services that are provided in the region, and expected outcomes from these activities. Thanks go to the local staff for their input and support in developing this Plan. 4 Central Australia Regional Overview In the very heart of the nation is the Central Australia Region, covering some 830,000 square kilometres. Encompassing the Simpson and Tanami Deserts and Barkly Tablelands, Central Australia shares borders with South Australia, Queensland and Western Australia. The Central Australia Region has a population of 46,315, of which 44 per cent identify as Indigenous Australians (2007). 1 Approximately 32,600 people live in the three largest centres of Alice Springs (28,000), Tennant Creek (3,000) and Yulara (1,600). The remainder of the population reside in the 45 remote communities and out-stations. Territory 2030, the Northern Territory Government’s plan for the future, identifies 20 Growth Towns, five of which are in Central Australia – Elliott, Ali Curung, Yuendumu, Ntaria (Hermannsburg) and Papunya. -

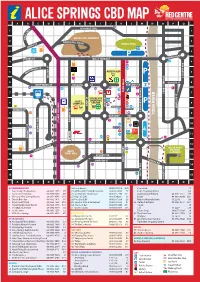

Alice Springs Cbd Map a B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q 14 Schwarz Cres 1 Es 1 R C E

ALICE SPRINGS CBD MAP A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q 14 SCHWARZ CRES 1 ES 1 R C E L E ANZAC HILL LOOKOUT H 2 ZAC H 2 AN ILL ROAD ST ANZAC OVAL TH SMI 3 P 3 UNDOOLYA RD STOKES ST WILLS TERRACE 4 8 22 4 12 LD ST 28 ONA 5 CD ALICE PLAZA 5 M P 32 LINSDAY AVE LINSDAY COLSON ST COLSON 4 6 GOYDER ST 6 WHITTAKER ST PARSONS ST PARSONS ST 43 25 20 21 9 1 29 TODD TODD MALL 7 38 STURT TERRACE 7 11 2 YEPERENYE 16 COLES SHOPPING 36 8 CENTRE 48 P 8 COMPLEX 15 BATH ST BATH 33 HARTLEY ST REG HARRIS LN 45 27 MUELLER ST KIDMAN ST 23 FAN ARCADE LEICHARDT TERRACE LEICHARDT 9 37 35 10 9 GREGORY TCE RIVER TODD 7 RAILWAY TCE RAILWAY 10 HIGHWAY STUART 10 24 41 46 P 47 GEORGE CRES GEORGE 44 WAY ONE 11 32 11 26 40 TOWN COUNCIL FOGARTY ST LAWNS 3 5 34 12 STOTT TCE 12 42 OLIVE PARK LARAPINTA DRV BOTANIC BILLY 39 31 GARDENS 13 GOAT HILL 13 6 13 STUART TCE 18 TUNCKS RD SIMPSON ST STREET TODD 14 19 14 17 49 15 SOUTH TCE 15 BARRETT DRV A B C D E F G H I J K L M N O P Q ACCOMMODATION 24. Loco Burrito 08 8953 0518 K10 Centrelink F5 1. Alice Lodge Backpackers 08 8953 1975 P7 25. McDonald’s Family Restaurant 08 8952 4555 E7 Coles Shopping Centre G8 2. -

GREAT DESERT SKINK TJAKURA Egernia Kintorei

Threatened Species of the Northern Territory GREAT DESERT SKINK TJAKURA Egernia kintorei Conservation status Australia: Vulnerable Northern Territory: Vulnerable Photo: Steve McAlpin Description southern sections of the Great Sandy Desert of Western The great desert skink is a large, smooth bodied lizard with an average snout-vent length of 200 mm (maximum of 440 mm) and a body mass of up to 350 g. Males are heavier and have broader heads than females. The tail is slightly longer than the snout-vent length. The upperbody varies in colour between individuals and can be bright orange- brown or dull brown or light grey. The underbody colour ranges from bright lemon- yellow to cream or grey. Adult males often have blue-grey flanks, whereas those of females and juveniles are either plain brown or vertically barred with orange and cream. Known locations of great desert skink. Distribution The great desert skink is endemic to the Australia. Its former range included the Great Australian arid zone. In the Northern Territory Victoria Desert, as far west as Wiluna, and the (NT), most recent records (post 1980) come Northern Great Sandy Desert. from the western deserts region from Uluru- Conservation reserves where reported: Kata Tjuta National Park north to Rabbit Flat in the Tanami Desert. The Tanami Desert and Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, Watarrka Uluru populations are both global strongholds National Park and Newhaven Reserve for the species. (managed for conservation by the Australian Wildlife Conservancy). Outside the NT it occurs in North West South Australia and in the Gibson Desert and For more information visit www.denr.nt.gov.au Ecology qualifies as Vulnerable (under criteria C2a(i)) due to: The great desert skink occupies a range of • population <10,000 mature individuals; vegetation types with the major habitat being • continuing decline, observed, projected or sandplain and adjacent swales that support inferred, in numbers; and hummock grassland and scattered shrubs. -

Evidence of Altered Fire Regimes in the Western Desert Region of Australia

272 Conservation Science W. Aust. 5 (3)N.D. : 272–284 Burrows (2006) et al. Evidence of altered fire regimes in the Western Desert region of Australia N.D. BURROWS1, A.A. BURBIDGE2, P.J. FULLER3 AND G. BEHN1 1Department of Conservation and Land Management, Locked Bag 104, Bentley Delivery Centre, Bentley, Western Australia, 6983. 2Department of Conservation and Land Management, Western Australian Wildlife Research Centre, P.O. Box 51, Wanneroo, Western Australia, 6946. 33 Willow Rd, Warwick, Western Australia, 6024. SUMMARY and senescing vegetation or vast tracts of vegetation burnt by lightning-caused wildfires. The relatively recent exodus of Aboriginal people from parts of the Western Desert region of Australia has coincided with an alarming decline in native mammals INTRODUCTION and a contraction of some fire sensitive plant communities. Proposed causes of these changes, in what The Great Victoria, Gibson, Great Sandy and Little Sandy is an otherwise pristine environment, include an altered Deserts (the Western Desert) occupy some 1.6 million fire regime resulting from the departure of traditional km2 of Western Australia, of which more than 100 000 Aboriginal burning, predation by introduced carnivores km2 is managed for nature conservation. The and competition with feral herbivores. conservation reserves in the Western Desert are large, Under traditional law and custom, Aboriginal people remote and relatively undisturbed. A management option inherit, exercise and bequeath customary responsibilities for such reserves is not to intervene -

Appropriate Terminology, Indigenous Australian Peoples

General Information Folio 5: Appropriate Terminology, Indigenous Australian Peoples Information adapted from ‘Using the right words: appropriate as ‘peoples’, ‘nations’ or ‘language groups’. The nations of terminology for Indigenous Australian studies’ 1996 in Teaching Indigenous Australia were, and are, as separate as the nations the Teachers: Indigenous Australian Studies for Primary Pre-Service of Europe or Africa. Teacher Education. School of Teacher Education, University of New South Wales. The Aboriginal English words ‘blackfella’ and ‘whitefella’ are used by Indigenous Australian people all over the country — All staff and students of the University rely heavily on language some communities also use ‘yellafella’ and ‘coloured’. Although to exchange information and to communicate ideas. However, less appropriate, people should respect the acceptance and use language is also a vehicle for the expression of discrimination of these terms, and consult the local Indigenous community or and prejudice as our cultural values and attitudes are reflected Yunggorendi for further advice. in the structures and meanings of the language we use. This means that language cannot be regarded as a neutral or unproblematic medium, and can cause or reflect discrimination due to its intricate links with society and culture. This guide clarifies appropriate language use for the history, society, naming, culture and classifications of Indigenous Australian and Torres Strait Islander people/s. Indigenous Australian peoples are people of Aboriginal and Torres -

Supplementary

Step 4: Interpretation We hope this approach has shorty Jangala robertson, Warlpiri, they unleashed a great thunderstorm enhanced your exploration and born about 1935, Yuendumu, Western that ultimately created the large un- Interpretation involves bringing enjoyment of this painting. If you desert, Northern territory derground wells that are represented your close observation, analysis, by the repeated concentric circles. A Closer Look like, you can try this method and any additional information Ngapa Jukurrpa—Puyurru with other works of art. simply these “water holes” provide both you have gathered about a work (Water Dreaming at Puyurru) physical and spiritual sustenance to ask yourself with each work: of art together to try to under- 2007 the region’s Warlpiri people. the long stand what it means. curving yellow lines in the painting What do I see? Acrylic on canvas Promised gift of Will owen and harvey represent the fast-flowing rivers that (Close observation) there can be multiple interpreta- Wagner; eL.2011.60.45 form after a heavy rain. the lines that tions of a work of art. the best- cross between the curving lines suggest What do I think? informed ones are based on visual the lightning and rain-making clouds. (Analysis) Aboriginal Australian painting is often the fields of colored dots allude to the evidence and accurate research. inspired by a particular place, but it flowering of the desert after the rain, How can I learn more? also represents, through a sophisticated but the energy that they create on the some interpretive questions to (research) visual language, ancient stories about surface of the canvas also suggests the consider for this painting might the ancestors who visited and shaped continual spiritual presence of the include the following: What might it mean? that place, information about how to Ancestors.