Toccata Classics TOCC0204 Notes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

Schubert and Liszt SIMONE YOUNG’S VISIONS of VIENNA

Schubert and Liszt SIMONE YOUNG’S VISIONS OF VIENNA 21 – 24 AUGUST SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE CONCERT DIARY NEW SEASON AUGUST Beethoven and Brahms Cocktail Hour Fri 23 Aug, 6pm BEETHOVEN String Quartet in E minor, Sat 24 Aug, 6pm Op.59 No.2 (Razumovsky No.2) Sydney Opera House, BRAHMS String Quintet No.2 Utzon Room Musicians of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra Abercrombie & Kent Shostakovich Symphony No.4 Masters Series JAMES EHNES PLAYS KHACHATURIAN Wed 28 Aug, 8pm KHACHATURIAN Violin Concerto Fri 30 Aug, 8pm SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No.4 Sat 31 Aug, 8pm Sydney Opera House Mark Wigglesworth conductor James Ehnes violin SEPTEMBER Geoffrey Lancaster in Recital Mon 2 Sep, 7pm City Recital Hall MOZART ON THE FORTEPIANO MOZART Piano Sonata in B flat, K570 MOZART Piano Sonata in E flat, K282 MOZART Rondo in A minor, K511 MOZART Piano Sonata in B flat, K333 Geoffrey Lancaster fortepiano Music from Swan Lake Wed 4 Sep, 7pm Thu 5 Sep, 7pm BEAUTY AND MAGIC Concourse Concert Hall, ROSSINI The Thieving Magpie: Overture Chatswood RAVEL Mother Goose: Suite TCHAIKOVSKY Swan Lake: Suite Umberto Clerici conductor Star Wars: The Force Awakens Sydney Symphony Presents Thu 12 Sep, 8pm in Concert Fri 13 Sep, 8pm Watch Wednesdays 8.30pm Set 30 years after the defeat of the Empire, Sat 14 Sep, 2pm this instalment of the Star Wars saga sees original Sat 14 Sep, 8pm or catch up On Demand cast members Carrie Fisher, Mark Hamill and Sydney Opera House Harrison Ford reunited on the big-screen, with the Orchestra playing live to film. -

MUSIK NACHRICHTEN AUS I PRAG

^^^m £//- OöZ MUSIK NACHRICHTEN AUS i PRAG GRUNDPROBLEME DER KUNSTLERISCHEN UND VOR ALLEM DER KONZERTTÄTIGKEIT #\i DER CSSR Vor kurzem berichteten wir in den Musiknachrichten aus Prag über einige Erfahrungen aus den soziologi schen Forschungen auf dem Gebiet der Musik. Heute wollen wir über weitere Ergebnisse der Arbeiten auf diesem Gebiet, die in der ganzen Welt immer größeres Interesse erweckten, berichten, die vielleicht auch im internationalen Sinn breitere und allgemeinere Gültigkeit haben, obwohl sie begreiflicherweise von bestimm ten, ganz spezifischen Voraussetzungen des Musiklebens in der Tschechoslowakei ausgehen. In dieser Abhandlung werden wir uns nur mit der quantitativen rung mit der künstlerischen Aktivität. Noch geringer ist dieser Analyse der künstlerischen Tätigkeit befassen, die w!r für Prozentsatz auf dem Gebiet der Konzerttätigkeit, weil, wie wichtig halten und als Ausgangspunkt für in der Anschrift an übrigens auch aus einigen nachfolgenden Angaben hervorgeht, gegebenen Problematik betrachten. Unsere Untersuchungen bei uns die Theatervorstellungen eine dominierende Stellung waren ausschließlich auf Theater, Musik und bildende Kunst einnehmen. gerichtet, das heißt auf öffentliche Theatervorstellungen, Kon Aus der erwähnten Tatsache geht es hervor, daß es bei uns zerte und Kunstausstellungen, ohne Rücksicht auf ihr Niveau immer noch maximale Reserven an Zuschauern und Zuhören auf ihre Organisation oder Einstellung. Aus dem Gesamtkomplex gibt die durch intensive und gut organisierte ästhetische Er der gegenwärtigene Kunstgattungen wurden nur drei - man ziehung den Besuch, eventuell auch die Produktion der künst könnte sagen dis klassischen Sparten mit jahrhundertalter lerischen Einrichtungen wesentlich steigern könnten, und daß Tradition und ausgeprägten Formen herausgegriffen. Nicht die künstlerische Aktivität bei weitem nicht ausreicht, um die entscheidend war dabei, ob es sich um professionelle Künsler Nachfrage zu befriedigen. -

The Life of an Artist Maria Bjørnson at Work on Janácek from the House Of

www.thescenographer.com Publisher Harman Publishing Ltd. - 1-5 Lillie Road, London SW6 1TX, UK Editor-in-chief/Art Director Paolo Felici Graphic Design Paolo Biagini - www.studiobiagini.com Contributors Santi Centineo, Martyn Hayes, Cameron Mackintosh, Adam Pollock, David Pountney, Isabella Vesco, Sue Willmington, Francesca Zambello Special Contributors Michael Lee, Olivia Temple (The Maria Bjørnson Archive - Redcase Ltd) Really Useful Group Ltd, Cameron Mackintosh Ltd DISTRIBUTION Europe Central Books - www.centralbooks.com USA - CANADA Disticor Magazine Distribution Services - www.disticor.com Subscriptions [email protected] ©2002 The Scenographer Magazine (All rights reserved) Printed in Great Britain XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX All artistic material published is the sole property of the authors cited. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without prior permission of the publisher. C M a o r n l F i a O a r s s T o t t h B m a e j T W ø w g h r N i M M t e o n o n h r g r a a F s L e r k 42 5 2 k c r 4 o i a 2 D S t i f I M b i A n a n s n a H e a h d a a c v 4 T e n a g o a e b i e t r n d a t s m e o u i B t c d l 8 6 h t w P 8 i l f C s 7 j n a o a o P ø e e u r o E n l H Z i V o w r a n a t l a a t i e l f t o n g n i m y o h s s n o n c e c s i e f t b e k s r t n o o A o e y M N i h k a l n t n r l o e l a g h ’ t o s r e P i C n s l i h e a t u D a T g J b e n a a e a t c n d o y á S m c e k s k e t T c o h u e s T s s a b r i y i n b M t u L a t r ’ e i O a t u B o v j e ø r M r t n o O s u a o S r r c n e p i t a o e b c B i e j a r ø l r 2 I n s 0 s s 0 o u n 9 e The Maria Bjørnson Archive is delighted to be involved in this special Tribute A personal tribute from Cameron Mackintosh ccasionally in life a thought comes into one’s head as if by magic and the result Ois something quite extraordinary. -

2018 WASO's Favourites

PROGRAM WASO’s Favourites 90TH ANNIVERSARY SEASON OPENING Fri 9 February 2018, 7.30pm Sat 10 February 2018, 2pm Perth Concert Hall Frankie Lo Surdo, French Horn BRONWYNROGERS.COM WESF1389A 1389_WESF - Arts Sponsorship Campaign 2016 - WASO_Program Ad_210x148mm_V2.indd 1 20/07/16 2:21 PM The West Australian Symphony Orchestra respectfully acknowledges the Traditional Owners, Custodians and Elders of the Indigenous Nations across Western Australia and on whose Lands we work. Welcome From the Minister It is my great pleasure to welcome you to the West Australian Symphony Frankie Lo Surdo, French Horn Orchestra’s opening concert for 2018. On this occasion I would like to acknowledge WASO’s significant contribution to WA’s cultural vibrancy for 90 years. WASO is undoubtedly one of our state’s cultural gems – it’s the largest and busiest performing arts organisation in WA, and has a reputation for excellence, engagement and innovation. WASO is one of Australia’s finest orchestras, and renowned internationally for their dynamic performances under Principal Conductor Asher Fisch. The Orchestra is also highly regarded for having the broadest and deepest community engagement program of any orchestra in the country. Our state is richer for the work of WASO, and I thank you all for your support of this outstanding Orchestra. David Templeman Minister for Culture and the Arts BRONWYNROGERS.COM WESF1389A 3 1389_WESF - Arts Sponsorship Campaign 2016 - WASO_Program Ad_210x148mm_V2.indd 1 20/07/16 2:21 PM Welcome From the Chairman Welcome to WASO's first concert of 2018, our 90th anniversary year. In order to achieve such a significant milestone, WASO has benefitted from the extraordinary long-term support of the people of Western Australia, and for that we are truly thankful. -

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings of the Year 2017

MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL Recordings Of The Year 2017 This is the fourteenth year that Musicweb International has asked its reviewing team to nominate their recordings of the year. Reviewers are not restricted to discs they had reviewed, but the choices must have been reviewed on MWI in the last 12 months (December 2016-November 2017). The 136 selections have come from 27 members of the team and 68 different labels, the choices reflecting as usual, the great diversity of music and sources. Of the selections, seven have received two nominations: Iván Fischer’s Mahler 3 on Channel Classics Late works by Elliott Carter on Ondine Tommie Haglund’s Cello concerto on BIS Beatrice Rana’s Goldberg Variations on Warner Unreleased recordings by Wanda Luzzato on Rhine Classics Krystian Zimerman’s late Schubert sonatas on Deutsche Grammophon Vaughan Williams London Symphony on Hyperion Two labels – Deutsche Grammophon and Hyperion – gained the most nominations, nine apiece, considerably more than any other label. MUSICWEB INTERNATIONAL RECORDING OF THE YEAR In this twelve month period, we published more than 2700 reviews. There is no easy or entirely satisfactory way of choosing one above all others as our Recording of the Year. In some years, there have been significant anniversaries of composers or performers to help guide the selection, but not so in 2017. Johann Sebastian BACH Goldberg Variations - Beatrice Rana (piano) rec. 2016 WARNER CLASSICS 9029588018 In the end, it was the unanimity of the two reviewers who nominated Beatrice Rana’s Goldberg Variations – “easily my individual Record of the Year” and “how is it possible that she can be only 23” – that won the day. -

06Human Locomotion a SKUTR

ČÍSLO 6 / ÚNOR 2014 / 131. SEZONA 2013–2014 / WWW.NARODNI-DIVADLO.CZ 06 Human Locomotion a SKUTR Rozhovor k premiéře Laterny magiky 14 Molièrův Tartuffe v Národním divadle po osmé FOTO: M. VOLF FOTO: ČINOHRA / DRAMA OPERA BALET / BALLET LATERNA MAGIKA Umělecký šéf / Artistic director: Ředitelka Opery Národního divadla Umělecký šéf / Artistic director: Šéf Laterny magiky / Director of the Michal Dočekal a Státní opery / Director of the National Petr Zuska Laterna magika: Zdeněk Prokeš Theatre Opera and the State Opera: Silvia Hroncová Umělecký ředitel Opery Národního NÁRODNÍ DIVADLO / divadla a Státní opery / Artistic director NÁRODNÍ DIVADLO / NOVÁ SCÉNA / THE NATIONAL THEATRE of the National Theatre Opera and the THE NATIONAL THEATRE THE NEW STAGE Josef Kajetán Tyl State Opera: Petr Kofroň Česká baletní symfonie II / Human Locomotion Strakonický dudák / Hudební ředitel Opery Národního The Czech Ballet Symphony II Koncept/Concept: SKUTR, Kopecký, The Bagpiper of Strakonice divadla / Musical director of the Polní mše / Field Mass Kodet Režie / Stage direction: J. A. Pitínský National Theatre Opera: Robert Jindra Hudba / Music: Bohuslav Martinů Režie/Stage direction: Martin Premiéra / Premiere: 5. 12. 2013 Hudební ředitel Státní opery / Choreografie / Choreography: Kukučka a Lukáš Trpišovský (SKUTR) Musical director of the State Opera: Jiří Kylián Choreografie/Choreography: Karel a Josef Čapkovi Martin Leginus Stabat Mater Jan Kodet Ze života hmyzu / Hudba / Music: Antonín Dvořák Scénografie/Set designer: Pictures from the Insects‘ Life -

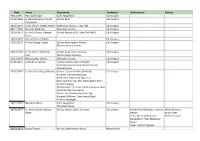

GC Archive by Date

Date Venue Programme Conductor Orchestra etc Soloists 09/12/1967 RDS, Ballsbridge Bach: Magnificat Cáit Cooper 01/05/1968 St. Bartholomew’s Church, Schütz, Bach Cáit Cooper Clyde Road 28/05/1970 Christ Church, Leeson Street Beethoven: Mass in C (Op. 86) Cáit Cooper 09/12/1970 Sion Hill, Blackrock Christmas Concert Cáit Cooper 22/04/1971 St. Ann’s Church, Dawson Schütz: Passion of St. John (SWV 481) Cáit Cooper Street 16/01/1972 Gaiety Theatre, Dublin Cáit Cooper 27/10/1972 Trinity College Chapel Schütz: Resurrection History Cáit Cooper (Tercentenary concert) 29/10/1972 Christ Church Cathedral , Schütz: Resurrection History Cáit Cooper Cork (Tercentenary concert) 17/12/1972 Municipal Art Gallery Christmas Concert Cáit Cooper 01/05/1973 Cork Choral Festival Frank Corcoran: Dán Aimhirghín Cáit Cooper (Commissioned by Cork Choral Festival) Competition B 27/05/1973 St. Kieran’s College, Kilkenny Schütz: Cantate Domino (SWV 81) Cáit Cooper Bruckner: Christus factus est Beethoven: Kyrie from Mass in C Bach: Ach Herr, lass dein lieb Engelein (from St. John Passion) Mendelssohn: Der erste Frühlingstag (exerpts) Corcoran: Dán Aimhirghín Distler: Ein Stündlein wohl vor Tag Vaughan Williams: Come Away Death Brahms, Madrigals 16/12/1973 National Gallery Bach: Magnificat Cáit Cooper Christmas Carols 28/01/1974 St. Ann's Church, Dawson Schütz, Hassler, Bach, Corcoran Cáit Cooper Violin: Brian McNamara, Loreto Alison Browner Street Nelson June Croker Cello: Una Ó Súilleabháin Richard Cooper Harpsichord: Hans Waldemar Rosen Organ: William Watson 24/03/1974 Gaiety Theatre Berlioz: Damnation of Faust Albert Rosen Date Venue Programme Conductor Orchestra etc Soloists 01/05/1974 Metropolitan Hall Feis Ceoil, Alice Yoakley Quirk Cup Cáit Cooper Competition: First Prize 01/05/1974 Cork Choral Festival Orff: Odi et Amo (Carmina Catulli) Cáit Cooper Kodaly: To the Transylvanians Distler: Ein Stündlein wohl vor Tag 25/06/1974 St. -

TOCC0422DIGIBKLT.Pdf

ADDING MY LITTLE BIT: WHY I COMPOSE by Jerome de Bromhead Composing nowadays is an almost quixotic pursuit, and the tangible rewards are indeed few. When I am asked why I do it, I usually reply: ‘Because I can, and therefore I must’. Te rewards are no less real because they are rare. Te satisfaction I get by hearing my work performed with understanding and feeling is intense and enduring. Te art of music is, to me, a serious pursuit – as serious as love or death. I was born in Waterford in the south-east of Ireland in 1945, the youngest of seven in a family that was comfortably of. My father, who was born in Yorkshire, had an ancestor who saddled the family with this surname. In the seventeenth century a Mr Bromhead of Yorkshire married a Miss de Gonville, who came from France (she may have been Huguenot). Tey ‘double-barrelled’ at frst as ‘de Gonville Bromhead’ but later shortened it by dropping ‘Gonville’, which was then used as a frst name in some branches of the family.1 My other ancestors were Irish with a sprinkling of French. My immediate family’s main interest was in things equestrian, and some of my relatives distinguished themselves in that sphere. Where horses were concerned, I was neither interested nor particularly useful – although I do remember the unique exhilaration of riding a thoroughbred at full gallop. My mother was the only member of the household who could not sing in tune. Tat didn’t deter her even slightly, and so at an early age I was introduced to manifestations of aleatoric atonality. -

FORGOTTEN ARTISTS an Occasional Series by Christopher Howell 24

FORGOTTEN ARTISTS An occasional series by Christopher Howell 24. TIBOR PAUL (1909-1973) Index of all articles in this series One Hungarian leads to another. Did not George Mikes, author of the hilarious “How to be an Alien”, develop the theory that “everybody is a Hungarian”? In the wake of my article on Carl Melles, a reader who has enriched the Forgotten Artists series with useful advice and recordings asked if I remembered anything about another Hungarian émigré, Tibor Paul. To tell the truth, my only memory came from the late 1960s, when newsagents’ racks were swamped with LPs selling at ten shillings or little more. I remember noting – but not buying – a Fontana LP in which a selection of Brahms Hungarian Dances and Dvořák Slavonic Dances were played by the Vienna Symphony Orchestra conducted, respectively, by Tibor Paul and Karel Ančerl. Since so many of those dirt cheap LPs had pseudonymous performers, I rather supposed that Tibor Paul was an invented name. It is, after all, the sort of Hungarian-sounding name you would come up with if you needed one in a hurry. About a decade later, after I had moved to Italy, I saw his name in the Radio Corriere conducting one of the RAI orchestras and thought, well, he must be real, then. If I had been based in Australia or Eire, I now see, I would have known better all along. The BBC Genome site suggests that he was a rare guest with UK orchestras. The item I saw in the Radio Corriere was almost certainly Viotti’s 22nd Violin Concerto, in which Paul accompanied Franco Gulli. -

British and Commonwealth Symphonies from the Nineteenth Century to the Present

BRITISH AND COMMONWEALTH SYMPHONIES FROM THE NINETEENTH CENTURY TO THE PRESENT A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Composers A-G KATY ABBOTT (b. 1971) She studied composition with Brenton Broadstock and Linda Kouvaras at the University of Melbourne where she received her Masters and PhD. In addition to composing, she teaches post-graduate composition as an onorary Fellow at University of Melbourne.Her body of work includes orchestral, chamber and vocal pieces. A Wind Symphony, Jumeirah Jane was written in 2008. Symphony No. 1 "Souls of Fire" (2004) Robert Ian Winstin//Kiev Philharmonic Orchestra (included in collection: "Masterworks of the New Era- Volume 12") ERM MEDIA 6827 (4 CDs) (2008) MURRAY ADASKIN (1905-2002) Born in Toronto. After extensive training on the violin he studied composition with John Weinzweig, Darius Milhaud and Charles Jones. He taught at the University of Saskatchewan where he was also composer-in-residence. His musical output was extensive ranging from opera to solo instrument pieces. He wrote an Algonquin Symphony in 1958, a Concerto for Orchestra and other works for orchestra. Algonquin Symphony (1958) Victor Feldbrill/Toronto Symphony Orchestra ( + G. Ridout: Fall Fair, Champagne: Damse Villageoise, K. Jomes: The Jones Boys from "Mirimachi Ballad", Chotem: North Country, Weinzweig: Barn Dance from "Red Ear of Corn" and E. Macmillan: À Saint-Malo) CITADEL CT-601 (LP) (1976) Ballet Symphony (1951) Geoffrey Waddington/Toronto Symphony Orchestra (included in collection: “Anthology Of Canadian Music – Murray Adaskin”) RADIO CANADA INTERNATIONAL ACM 23 (5 CDs) (1986) (original LP release: RADIO CANADA INTERNATIONAL RCI 71 (1950s) THOMAS ADÈS (b. -

Download Archive Guinness Choir Phd Scholarship

Guinness Choir PhD Scholarship in collaboration with TU Dublin Conservatoire The Guinness choir is celebrating its seventieth anniversary and recently has deposited its library and archives in the library of TU Dublin Conservatoire in Grangegorman as part of a collaborative venture between the choir and the Conservatoire’s Research Foundation for Music in Ireland. As part of the celebrations the Guinness Choir is offering a PhD scholarship for a student who will undertake a research project centred on the history of the choir. In addition to the extensive choir library, the archive contains wide ranging administrative records and ephemera. The records have been meticulously kept and are very rich in detail. Fascinating aspects of the archive include correspondence relating to the planning of concerts and other matters, concert programmes, press releases, reviews and detailed financial reports and accounts. It also contains some interesting reflections on concerts. An opportunity to interview and record the memories of some founding members and others with long associations is also possible. Combined, these provide an array of sources to examine the history of the choir. Such a history will place the work of the choir in the wider context of choral music in Ireland. It will also contain some very interesting personal stories and fill in many gaps in our understanding of choral music in Dublin. The scholarship offered will cover 50% of the fulltime fees for PhD (current fees, €4,500 per annum) up to a maximum of four years or part time fees (current fees, €3,000 per annum) up to a maximum of six years Background to The Guinness Choir The Guinness Choir, aka the St James’s Gate Musical Society, (orginally composed of brewery employees and their families) was established in 1951 by Victor Leeson, who conducted the Choir from its foundation until his retirement in 1984.