FORGOTTEN ARTISTS an Occasional Series by Christopher Howell 24

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

(WA) from 1938 to 1980 and Its Role in the Cultural Life of Perth

The Fellowship of Australian Writers (WA) from 1938 to 1980 and its role in the cultural life of Perth. Patricia Kotai-Ewers Bachelor of Arts, Master of Philosophy (UWA) This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Murdoch University November 2013 ABSTRACT The Fellowship of Australian Writers (WA) from 1938 to 1980 and its role in the cultural life of Perth. By the mid-1930s, a group of distinctly Western Australian writers was emerging, dedicated to their own writing careers and the promotion of Australian literature. In 1938, they founded the Western Australian Section of the Fellowship of Australian Writers. This first detailed study of the activities of the Fellowship in Western Australia explores its contribution to the development of Australian literature in this State between 1938 and 1980. In particular, this analysis identifies the degree to which the Fellowship supported and encouraged individual writers, promoted and celebrated Australian writers and their works, through publications, readings, talks and other activities, and assesses the success of its advocacy for writers’ professional interests. Information came from the organisation’s archives for this period; the personal papers, biographies, autobiographies and writings of writers involved; general histories of Australian literature and cultural life; and interviews with current members of the Fellowship in Western Australia. These sources showed the early writers utilising the networks they developed within a small, isolated society to build a creative community, which welcomed artists and musicians as well as writers. The Fellowship lobbied for a wide raft of conditions that concerned writers, including free children’s libraries, better rates of payment and the establishment of the Australian Society of Authors. -

Aoife Miskelly Soprano

Aoife Miskelly Soprano Northern Irish soprano Aoife Miskelly Codetta in their performance – live on studied as a Sickle Foundation Scholar on the Spanish radio – of Beethoven’s oratorio Christ Opera Masters degree course at the Royal on the Mount of Olives in Cuenca. Aoife is also Academy of Music in London, graduating in a very keen oratorio singer, having performed 2012 with the Regency Award. During her in a whole host of concerts, including Bach’s studies, Aoife was a Kathleen Ferrier Awards Christmas Oratorio, St. John and Matthew finalist (2010), won a BBC Northern Ireland Passions, Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen and Young Artists Platform Award, and was a Magnificat, Beethoven’s Mass in C (in Samling Scholar, Internationale Cologne Cathedral), Brahms’ Deutches Meistersinger Akademie Young Artist and Requiem (St. Martin in the Fields), Carissimi’s Britten-Pears Young Artist. Aoife was the Jepthe (St. John’s, Smith Square), Handel’s winner of the Hampshire National Singing Messiah, Dixit Dominus, Laudate Pueri Competition in 2011, the Bernadette Greevy Dominum, and Saul (conducted by Laurence Bursary in 2011, finalist in the Veronica Dunne Cummings), Mozart’s Requiem, Coronation International Singing Competition 2013, and Mass and Exultate Jubilate, Orff’s Carmina finalist in the 2015 Wigmore Hall Song Burana (Ulster Orchestra), Poulenc’s Gloria, Competition. Stravinsky’s Mass, Varese’s Nocturnal and Vivaldi’s Gloria. During the 2012-16 seasons Aoife was a soloist at the Cologne Opera House where she Aoife’s recent highlights include -

A Midsummer Night's Dream

Monday 25, Wednesday 27 February, Friday 1, Monday 4 March, 7pm Silk Street Theatre A Midsummer Night’s Dream by Benjamin Britten Dominic Wheeler conductor Martin Lloyd-Evans director Ruari Murchison designer Mark Jonathan lighting designer Guildhall School of Music & Drama Guildhall School Movement Founded in 1880 by the Opera Course and Dance City of London Corporation Victoria Newlyn Head of Opera Caitlin Fretwell Chairman of the Board of Governors Studies Walsh Vivienne Littlechild Dominic Wheeler Combat Principal Resident Producer Jonathan Leverett Lynne Williams Martin Lloyd-Evans Language Coaches Vice-Principal and Director of Music Coaches Emma Abbate Jonathan Vaughan Lionel Friend Florence Daguerre Alex Ingram de Hureaux Anthony Legge Matteo Dalle Fratte Please visit our website at gsmd.ac.uk (guest) Aurelia Jonvaux Michael Lloyd Johanna Mayr Elizabeth Marcus Norbert Meyn Linnhe Robertson Emanuele Moris Peter Robinson Lada Valešova Stephen Rose Elizabeth Rowe Opera Department Susanna Stranders Manager Jonathan Papp (guest) Steven Gietzen Drama Guildhall School Martin Lloyd-Evans Vocal Studies Victoria Newlyn Department Simon Cole Head of Vocal Studies Armin Zanner Deputy Head of The Guildhall School Vocal Studies is part of Culture Mile: culturemile.london Samantha Malk The Guildhall School is provided by the City of London Corporation as part of its contribution to the cultural life of London and the nation A Midsummer Night’s Dream Music by Benjamin Britten Libretto adapted from Shakespeare by Benjamin Britten and Peter Pears -

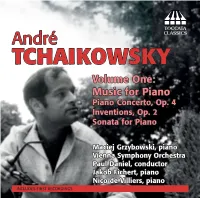

Toccata Classics TOCC0204 Notes

TOCCATA André CLASSICS TCHAIKOWSKY Volume One: Music for Piano Piano Concerto, Op. 4 Inventions, Op. 2 Sonata for Piano Maciej Grzybowski, piano P Vienna Symphony Orchestra Paul Daniel, conductor Jakob Fichert, piano Nico de Villiers, piano INCLUDES FIRST RECORDINGS ANDRÉ TCHAIKOWSKY: A LIFE WITH THE PIANO by Anastasia Belina-Johnson André Tchaikowsky was born on 1 November 1935, in Warsaw, and named Robert Andrzej Krauthammer. His parents separated, after a short marriage, before he was born, and he was brought up by his mother Felicja and grandmother Celina. As a child, the young Krauthammer was energetic and talkative; he absorbed languages and ideas at lightning speed, and enjoyed the attention of adults. By the age of three-and-a-half, he could read in Polish, German and Russian, and at the age of four his mother began to teach him piano. He was fascinated by the idea that one could read music in the same way as one reads written words, and his mother showed him the relationship between printed notes and piano keys. His grandmother immediately began to plan for his future, announcing that he would become the best and most famous pianist in the world. Just over a month before his fourth birthday, at the end of September 1939, the invading Germans occupied Warsaw. The Jews living there were ordered to relocate into a single neighbourhood in the centre, which was sealed by a wall in November 1940. When Celina’s apartment was enclosed into the ghetto area, she defiantly moved out, claiming to be a Christian, while Felicja decided to remain with her son. -

Bernadette Greevy Bursary for Singers 2019 Application Form

✁ Bernadette Greevy Bursary for Singers 2019 Application Form Name: Address: Email: Telephone number: BERNADETTE GREEVY Date of birth: Details of current study: BURSARY FOR SINGERS 2019 Details of music qualifications (e.g. B.Mus, Diplomas, etc.): Guidelines and Application Form Programme as submitted by mp3: Any other information that you feel is relevant to this application: Deadline: 5pm, Friday 3 May 2019 to [email protected] Thank you for your application. The National Concert Hall invites singers to apply for the Bernadette Guidelines Greevy Bursary. One singer will be awarded the bursary of €5,000 Entrants may be from all classical voice types. They must be Irish or living by the National Concert Hall, in honour of Irish mezzo-soprano Dr in Ireland, and in third-level education or equivalent. Bernadette Greevy. Entrants will submit: The winner of the Bernadette Greevy Bursary will give a recital at the National Concert Hall at the end of the following year, featuring • programme of their choice of not more than 15 minutes’ length a new Irish piece commissioned for the occasion. in mp3 format shared via wetransfer.com to [email protected]. Please include your name in the message field, but do not attach The Bernadette Greevy Bursary is kindly supported by the your name to the recording. Department of Culture, Heritage & the Gaeltacht. • an application form with personal details and the details of their programme. About Dr Bernadette Greevy • a letter of recommendation from their teacher. Dubliner Bernadette Greevy was the first Irish winner of Harriet Cohen International Music Award for Outstanding Artistry. -

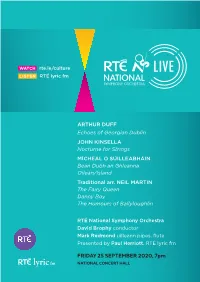

RTE NSO 25 Sept Prog.Qxp:Layout 1

WATCH rte.ie/culture LISTEN RTÉ lyric fm ARTHUR DUFF Echoes of Georgian Dublin JOHN KINSELLA Nocturne for Strings MÍCHEÁL Ó SÚILLEABHÁIN Bean Dubh an Ghleanna Oileán/Island Traditional arr. NEIL MARTIN The Fairy Queen Danny Boy The Humours of Ballyloughlin RTÉ National Symphony Orchestra David Brophy conductor Mark Redmond uilleann pipes, flute Presented by Paul Herriott, RTÉ lyric fm FRIDAY 25 SEPTEMBER 2020, 7pm NATIONAL CONCERT HALL 1 Arthur Duff 1899-1956 Echoes of Georgian Dublin i. In College Green ii. Song for Amanda iii. Minuet iv. Largo (The tender lover) v. Rigaudon Arthur Duff showed early promise as a musician. He was a chorister at Dublin’s Christ Church Cathedral and studied at the Royal Irish Academy of Music, taking his degree in music at Trinity College, Dublin. He was later awarded a doctorate in music in 1942. Duff had initially intended to enter the Church of Ireland as a priest, but abandoned his studies in favour of a career in music, studying composition for a time with Hamilton Harty. He was organist and choirmaster at Christ Church, Bray, for a short time before becoming a bandmaster in the Army School of Music and conductor of the Army No. 2 band based in Cork. He left the army in 1931, at the same time that his short-lived marriage broke down, and became Music Director at the Abbey Theatre, writing music for plays such as W.B. Yeats’s The King of the Great Clock Tower and Resurrection, and Denis Johnston’s A Bride for the Unicorn. The Abbey connection also led to the composition of one of Duff’s characteristic works, the Drinking Horn Suite (1953 but drawing on music he had composed twenty years earlier as a ballet score). -

Missing a Beat

Missing a Beat Bridging Ireland's Orchestral Gaps A Review of Orchestral Provision in Ireland Review of Orchestral Provision in Ireland 1 Introductory note from The Arts Council/An Chomhairle Ealaíon This note introduces the Report 'Missing a Beat: bridging Ireland's orchestral gaps', from the perspective of the Arts Council. In response to feedback gathered during a major consultation process (2005), in the resulting document, Partnership for the Arts, the Arts Council undertook to “examine national orchestral needs and develop appropriate responses”1. This led to commissioning a review of orchestral provision in late 2007. Much of the primary research was undertaken during 2008 and 2009. The resulting report 'Missing a Beat, Bridging Ireland's Orchestral Gaps' written by Fergus Sheil, was finalised in November 2010. A postscript to the original report was written by the author in May 2012, in order to reflect developments since the original report was completed. This postscript is now appended to the original document. The report offers an overview and analysis of issues affecting orchestral provision in Ireland. It draws upon a wide range of examples of international practice to illustrate what it regards as 'gaps' and to highlight the potential that may exist for development within Ireland. Beyond its usefulness as an important reference document, the report has the potential to stimulate both further dialogue and practical cooperation amongst a broad range of stakeholders within the music sector. In this regard, the report itself notes and anticipates the need for the music sector to develop new models of practice. Embracing such an approach may prove to be essential in terms of ensuring the longer term development and sustainability of orchestral music provision in Ireland. -

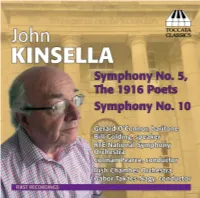

Toccata Classics TOCC0242 Notes

Americas, and from further aield: basically, if it’s good music and it hasn’t yet been recorded, JOHN KINSELLA, IRISH SYMPHONIST by Séamas da Barra John Kinsella was born in Dublin on 8 April 1932. His early studies at the Dublin College of Music were devoted to the viola as well as to harmony and counterpoint, but he is essentially self-taught as a composer. He started writing music as a teenager and although he initially adopted a straightforward, even conventional, tonal idiom, he began to take a serious interest in the compositional techniques of the European avant-garde from the early 1960s. He embraced serialism in particular as a liberating influence on his creative imagination, and he produced a substantial body of work during this period that quickly established him in Ireland as one of the most interesting younger figures of the day. In 1968 Kinsella was appointed Senior Assistant in the music department of Raidió Teilefís Éireann (RTÉ), the Irish national broadcasting authority, a position that allowed him to become widely acquainted with the latest developments in contemporary music, particularly through the International Rostrum of Composers organised under the auspices of UNESCO. But much of what he heard at these events began to strike him as dispiritingly similar in content, and he was increasingly persuaded that for many of his contemporaries conformity with current trends had become more P important than a desire to create out of inner conviction. As he found himself growing disillusioned with the avant-garde, his attitude to his own work began to change and he came to question the artistic validity of much of what he had written. -

Schubert and Liszt SIMONE YOUNG’S VISIONS of VIENNA

Schubert and Liszt SIMONE YOUNG’S VISIONS OF VIENNA 21 – 24 AUGUST SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE CONCERT DIARY NEW SEASON AUGUST Beethoven and Brahms Cocktail Hour Fri 23 Aug, 6pm BEETHOVEN String Quartet in E minor, Sat 24 Aug, 6pm Op.59 No.2 (Razumovsky No.2) Sydney Opera House, BRAHMS String Quintet No.2 Utzon Room Musicians of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra Abercrombie & Kent Shostakovich Symphony No.4 Masters Series JAMES EHNES PLAYS KHACHATURIAN Wed 28 Aug, 8pm KHACHATURIAN Violin Concerto Fri 30 Aug, 8pm SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No.4 Sat 31 Aug, 8pm Sydney Opera House Mark Wigglesworth conductor James Ehnes violin SEPTEMBER Geoffrey Lancaster in Recital Mon 2 Sep, 7pm City Recital Hall MOZART ON THE FORTEPIANO MOZART Piano Sonata in B flat, K570 MOZART Piano Sonata in E flat, K282 MOZART Rondo in A minor, K511 MOZART Piano Sonata in B flat, K333 Geoffrey Lancaster fortepiano Music from Swan Lake Wed 4 Sep, 7pm Thu 5 Sep, 7pm BEAUTY AND MAGIC Concourse Concert Hall, ROSSINI The Thieving Magpie: Overture Chatswood RAVEL Mother Goose: Suite TCHAIKOVSKY Swan Lake: Suite Umberto Clerici conductor Star Wars: The Force Awakens Sydney Symphony Presents Thu 12 Sep, 8pm in Concert Fri 13 Sep, 8pm Watch Wednesdays 8.30pm Set 30 years after the defeat of the Empire, Sat 14 Sep, 2pm this instalment of the Star Wars saga sees original Sat 14 Sep, 8pm or catch up On Demand cast members Carrie Fisher, Mark Hamill and Sydney Opera House Harrison Ford reunited on the big-screen, with the Orchestra playing live to film. -

MUSIK NACHRICHTEN AUS I PRAG

^^^m £//- OöZ MUSIK NACHRICHTEN AUS i PRAG GRUNDPROBLEME DER KUNSTLERISCHEN UND VOR ALLEM DER KONZERTTÄTIGKEIT #\i DER CSSR Vor kurzem berichteten wir in den Musiknachrichten aus Prag über einige Erfahrungen aus den soziologi schen Forschungen auf dem Gebiet der Musik. Heute wollen wir über weitere Ergebnisse der Arbeiten auf diesem Gebiet, die in der ganzen Welt immer größeres Interesse erweckten, berichten, die vielleicht auch im internationalen Sinn breitere und allgemeinere Gültigkeit haben, obwohl sie begreiflicherweise von bestimm ten, ganz spezifischen Voraussetzungen des Musiklebens in der Tschechoslowakei ausgehen. In dieser Abhandlung werden wir uns nur mit der quantitativen rung mit der künstlerischen Aktivität. Noch geringer ist dieser Analyse der künstlerischen Tätigkeit befassen, die w!r für Prozentsatz auf dem Gebiet der Konzerttätigkeit, weil, wie wichtig halten und als Ausgangspunkt für in der Anschrift an übrigens auch aus einigen nachfolgenden Angaben hervorgeht, gegebenen Problematik betrachten. Unsere Untersuchungen bei uns die Theatervorstellungen eine dominierende Stellung waren ausschließlich auf Theater, Musik und bildende Kunst einnehmen. gerichtet, das heißt auf öffentliche Theatervorstellungen, Kon Aus der erwähnten Tatsache geht es hervor, daß es bei uns zerte und Kunstausstellungen, ohne Rücksicht auf ihr Niveau immer noch maximale Reserven an Zuschauern und Zuhören auf ihre Organisation oder Einstellung. Aus dem Gesamtkomplex gibt die durch intensive und gut organisierte ästhetische Er der gegenwärtigene Kunstgattungen wurden nur drei - man ziehung den Besuch, eventuell auch die Produktion der künst könnte sagen dis klassischen Sparten mit jahrhundertalter lerischen Einrichtungen wesentlich steigern könnten, und daß Tradition und ausgeprägten Formen herausgegriffen. Nicht die künstlerische Aktivität bei weitem nicht ausreicht, um die entscheidend war dabei, ob es sich um professionelle Künsler Nachfrage zu befriedigen. -

Madame Ballet' As Establish a Perth-Based Ballet Company Western Australian Author Ffion Murphy As a Result of Those Who Had Prepared the Ground for Her

Michelle Potter reveals how Bousloff, whose youth had been lived out Russian dancer Kira Bousloff boldly of a suitcase as she travelled the world as a dancer with the Ballets Russescompanies created an environment for dance of Colonel de Basil, decided to remain in to flourish in Western Australia Australia in 1939 at the end of a tour by the Covent Garden Russian Ballet. She recalls When I came to the airport here in little Perth, that decision in an oral history interview at the end of the world, I put my feet on the recorded for the National Library in 1990: ground, I looked around, and I said loudly and strongly 'That's where I'm going to live and I was sitting in my hotel room in Melbourne that's where I'm going to die'. on my own and I had a strong feeling that my father (who had died many years ago) -Kira Bousloff touched my shoulder. It was a physical feeling practically. Then I had suddenly this strong ira Bousloff, or Kira Abricossova as feeling that I had to stay in Australia. So she was known during her early without even thinking twice (of course, you see, Kperforming career, was the founder of I'm a bit queer, eccentric, but that's the truth, the West Australian Ballet, one of Australia's that's what happened) I ran down the stairs and earliest state-based ballet companies-the rang up ... a very good friend and I said, 'I want first, in fact, to call itself a state company. -

PDF (Volume 2)

Durham E-Theses A.J. Potter (1918-1980): The career and creative achievement of an Irish composer in social and cultural context Zuk, Patrick How to cite: Zuk, Patrick (2007) A.J. Potter (1918-1980): The career and creative achievement of an Irish composer in social and cultural context, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/2911/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 Chapter4 Choral works with orchestra 4.1 Introduction n view of Potter's early training as a chorister, it is perhaps surprising to find that choral music comprises a comparatively small proportion of his output: I one might have expected him to follow up his early Missa Brevis with other substantial choral works of various kinds. The fact that he did not can undoubtedly be explained by the circumstances of Irish musical life at the period: in bleak contrast to Britain, not only were good choirs few and far between, but there was little evidence of interest in choral music throughout the country at large.