Georgian Abkhaz Youth Dialogue Workshop

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SHUSHA History, Culture, Arts

SHUSHA History, culture, arts Historical reference: Shusha - (this word means «glassy, transparent») town in the Azerbaijan Republic on the territory of Nagorny Karabakh. Shusha is 403 km away from Baku, it lies 1400 m above the sea levels, on Karabakh mountainous ridge. Shusha is mountainous-climatic recreation place. In 1977 was declared reservation of Azerbaijan architecture and history. Understanding that should Iranian troops and neighbor khans attack, Boy at fortress will not serve as an adequate shelter, Khan transferred his court to Shakhbulag. However, this fortress also could not protect against the enemies. That is why they had to build fortress in the mountains, in impassable, inaccessible place, so that even strong enemy would not be able to take it. The road to the fortress had to be opened from the one side for ilats from the mountains, also communication with magals should not be broken. Those close to Panakh Ali-khan advised to choose safer site for building of a new fortress. Today's Shusha located high in the mountains became that same place chosen by Panakh Ali- khan for his future residence. Construction of Shusha, its palaces and mosques was carried out under the supervision of great poet, diplomat and vizier of Karabakh khanate Molla Panakh Vagif. He chose places for construction of public and religious buildings (not only for Khan but also for feudal lords-»beys»). Thus, the plans for construction and laying out of Shusha were prepared. At the end of 1750 Panakh Ali-khan moved all reyats, noble families, clerks and some senior people from villages from Shakhbulag to Shusha. -

State Report Azerbaijan

ACFC/SR(2002)001 ______ REPORT SUBMITTED BY AZERBAIJAN PURSUANT TO ARTICLE 25, PARAGRAPH 1 OF THE FRAMEWORK CONVENTION FOR THE PROTECTION OF NATIONAL MINORITIES ______ (Received on 4 June 2002) _____ TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I............................................................................................................................................ 3 II. Aggression of the Republic of Armenia against the Republic of Azerbaijan..................... 9 III. Information on the form of the State structure.................................................................. 12 IV. Information on status of international law in national legislation .................................... 13 V. Information on demographic situation in the country ...................................................... 13 VI. Main economic data - gross domestic product and per capita income ............................. 15 VII. State’s national policy in the field of the protection of the rights of persons belonging to minorities ...................................................................................................................................... 15 VIII. Population awareness on international treaties to which Azerbaijan is a party to........ 16 P A R T II..................................................................................................................................... 18 Article 1 ........................................................................................................................................ 18 Article -

Key Considerations for Returns to Nagorno-Karabakh and the Adjacent Districts November 2020

Key Considerations for Returns to Nagorno-Karabakh and the Adjacent Districts November 2020 With the latest developments in the Nagorno-Karabakh (NK) region and seven adjacent districts, the issue of return of persons originating from these areas (IDPs and refugees1), who were displaced in the past and most recent conflicts, has emerged as a new core issue that is also specifically mentioned, along with UNHCR’s supervisory role in this regard, in the statement on cessation of hostilities issued by the parties on 9 November 2020 under the auspices of the Russian Federation.2 Regarding specifically the return of IDPs from Azerbaijan, according to different sources, the Azeri authorities developed in 2005 broad elements of an IDP return concept, together with international agencies, which emphasizes the principle of voluntary returns in dignity and safety.3 No such plan exists for the return of refugees and persons in a refugee-like situation in Armenia, as the displacement of the Armenian population from NK only took place recently. It is also to note that the recent developments in NK do not open the possibility for the return of ethnic Armenian refugees and former refugees, who were displaced in the early 1990s from Baku, Sumgait and other parts of Azerbaijan, nor for the return of ethnic Azeris who left Armenia proper and settled in Azerbaijan and were since naturalized. The purpose of this note is to spell out the basic parameters to be considered under international law for these returns with a view to inform UNHCR and the UN’s possible support and assistance role. -

Minsk Group Proposal ('Package Deal')

2014年7月9日 Nagorno-Karabakh: Documents, Resolutions and Agreements Minsk Group proposal ('package deal') July 1997 [unofficial translation] Comprehensive agreement on the resolution of the NagornoKarabakh conflict CoChairs of the Minsk Group of the OSCE Preamble: The Sides, recognizing fully the advantages of peace and cooperation in the region for the flourishing and wellbeing of their peoples, express their determination to achieve a peaceful resolution of the prolonged Nagorny Karabakh conflict. The resolution laid out below will create a basis for the joint economic development of the Caucasus, giving the peoples of this region the possibility of living a normal and productive life under democratic institutions, promoting wellbeing and a promising future. Cooperation in accordance with the present Agreement will lead to normal relations in the field of trade, transport and communications throughout the region, giving people the opportunity to restore, with the assistance of international organizations, their towns and villages, to create the stability necessary for a substantial increase in external capital investment in the region, and to open the way to mutually beneficial trade, leading to the achievement of natural development for all peoples, the basis for which exists in the Caucasus region. Conciliation and cooperation between peoples will release their enormous potential to the benefit of their neighbours and other peoples of the world. In accordance with these wishes, the Sides, being subject to the provisions of the UN Charter, the basic principles and decisions of the OSCE and universally recognized norms of international law, and expressing their determination to support the full implementation of UN Security Council Resolutions 822, 853, 874 and 884, agree herewith to implement the measures laid out in Agreement I in order to put an end to armed hostilities and reestablish normal relations, and to reach an agreement on the final status of Nagorny Karabakh, as laid out in Agreement II. -

Forced Displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh Conflict: Return and Its Alternatives

Forced displacement in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict: return and its alternatives August 2011 conciliation resources Place-names in the Nagorny Karabakh conflict are contested. Place-names within Nagorny Karabakh itself have been contested throughout the conflict. Place-names in the adjacent occupied territories have become increasingly contested over time in some, but not all (and not official), Armenian sources. Contributors have used their preferred terms without editorial restrictions. Variant spellings of the same name (e.g., Nagorny Karabakh vs Nagorno-Karabakh, Sumgait vs Sumqayit) have also been used in this publication according to authors’ preferences. Terminology used in the contributors’ biographies reflects their choices, not those of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. For the map at the end of the publication, Conciliation Resources has used the place-names current in 1988; where appropriate, alternative names are given in brackets in the text at first usage. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of Conciliation Resources or the European Union. Altered street sign in Shusha (known as Shushi to Armenians). Source: bbcrussian.com Contents Executive summary and introduction to the Karabakh Contact Group 5 The Contact Group papers 1 Return and its alternatives: international law, norms and practices, and dilemmas of ethnocratic power, implementation, justice and development 7 Gerard Toal 2 Return and its alternatives: perspectives -

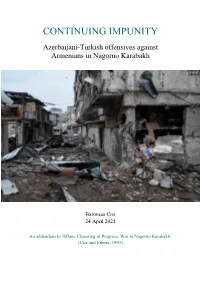

Continuing Impunity

CONTINUING IMPUNITY Azerbaijani-Turkish offensives against Armenians in Nagorno Karabakh Baroness Cox 24 April 2021 An addendum to ‘Ethnic Cleansing in Progress: War in Nagorno Karabakh’ (Cox and Eibner, 1993) CONTENTS Acknowledgements page 1 Introduction page 1 Background page 3 The 44-Day War page 3 Conclusion page 27 Appendix: ‘The Spirit of Armenia’ page 29 1. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to record my profound sympathy for all who suffered – and continue to suffer – as a result of the recent war and my deep gratitude to all whom I met for sharing their experiences and concerns. These include, during my previous visit in November 2020: the Presidents of Armenia and Nagorno Karabakh; the Human Rights Ombudsmen for Armenia and Nagorno Karabakh; members of the National Assembly of Armenia; Zori Balayan and his family, including his son Hayk who had recently returned from the frontline with his injured son; Father Hovhannes and all whom I met at Dadivank; and the refugees in Armenia. I pay special tribute to Vardan Tadevosyan, along with his inspirational staff at Stepanakert’s Rehabilitation Centre, who continue to co-ordinate the treatment of some of the most vulnerable members of their community from Yerevan and Stepanakert. Their actions stand as a beacon of hope in the midst of indescribable suffering. I also wish to express my profound gratitude to Artemis Gregorian for her phenomenal support for the work of my small NGO Humanitarian Aid Relief Trust, together with arrangements for many visits. She is rightly recognised as a Heroine of Artsakh as she stayed there throughout all the years of the previous war and has remained since then making an essential contribution to the community. -

11 December 2020 Excellency, We

PALAIS DES NATIONS • 1211 GENEVA 10, SWITZERLAND www.ohchr.org • TEL: +41 22 917 9543 / +41 22 917 9738 • FAX: +41 22 917 9008 • E-MAIL: [email protected] Mandates of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; the Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances; and the Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions REFERENCE: UA AZE 4/2020 11 December 2020 Excellency, We have the honour to address you in our capacity as Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances; and Special Rapporteur on extrajudicial, summary or arbitrary executions, pursuant to Human Rights Council resolutions 43/20, 45/3 and 44/5. In this connection, we would like to bring to the attention of your Excellency’s Government information we have received concerning torture and ill-treatment of prisoners of war and cases of enforced disappearance during the armed conflict in and around the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict zone. We also call on your Excellency’s Government to honour the ceasefire agreement to ensure lasting peace, including by returning captives and bodies of the dead to their respective countries of origin and to their families. Concerns regarding the hostilities was the subject of a previous Special Procedures communication (AZE 2/2020). We thank your Excellency’s Government for its responses. According to the information received: On 27 September 2020, large-scale military hostilities broke out along the Line of Contact in and around the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict zone. -

Administrative Territorial Divisions in Different Historical Periods

Administrative Department of the President of the Republic of Azerbaijan P R E S I D E N T I A L L I B R A R Y TERRITORIAL AND ADMINISTRATIVE UNITS C O N T E N T I. GENERAL INFORMATION ................................................................................................................. 3 II. BAKU ....................................................................................................................................................... 4 1. General background of Baku ............................................................................................................................ 5 2. History of the city of Baku ................................................................................................................................. 7 3. Museums ........................................................................................................................................................... 16 4. Historical Monuments ...................................................................................................................................... 20 The Maiden Tower ............................................................................................................................................ 20 The Shirvanshahs’ Palace ensemble ................................................................................................................ 22 The Sabael Castle ............................................................................................................................................. -

Human Rights Without Frontiers International

Human Rights Without Frontiers International Avenue d’Auderghem 61/16, 1040 Brussels Phone/ Fax: 32 2 3456145 Email: [email protected] – Website: http://www.hrwf.net OSCE Human Dimension Implementation Meeting Warsaw, 3 October 2011 Working Session 11: Humanitarian Issues and Other Commitments/ IDPs 600 000 IDPs waiting for 20 years to return to Nagorno-Karabakh and the 7 Azerbaijani districts occupied by Armenia 600 000 is the number of internally displaced people in Azerbaijan that the UNHCR mentioned in its report Global Trends in 2009. These 600 000 IDPs were violently forced from their homes during the armed aggression by the Republic of Armenia against Azerbaijan. More than 40,000 come from the Nagorno-Karabakh region and around 550,000 come from the seven surrounding districts of Azerbaijan. As a result of an ethnic cleansing perpetrated by the Armenian forces not a single Azerbaijani remained there. All these regions have been occupied by Armenia for almost 20 years despite numerous decisions adopted by the UN Security Council, UN General Assembly, OSCE and the Council of Europe. Since 1992, the political settlement of the conflict has been discussed within the framework of the OSCE Minsk Group with Russia, United States and France as its Co-Chairs. The peace talks were reinvigorated in 2009 with the promotion of the Basic Principles contained in the Madrid Document and the Statement by the OSCE Minsk Group Co-Chair countries on 10 July 2009. The Basic Principles call for: The return of the territories surrounding Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijani control; An interim status for Nagorno-Karabakh providing guarantees for security and self- governance; A corridor linking Armenia to Nagorno-Karabakh; Future determination of the final legal status of Nagorno-Karabakh through a legally binding expression of will; The right of all internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees to return to their former places of residence; International security guarantees that would include a peacekeeping operation. -

The Nagorno-Karabakh Settlement Revisited: Is Peace Achievable?

The Nagorno-Karabakh Settlement Revisited: Is Peace Achievable? LEVON ZOURABIAN Abstract: The twelve years of negotiations on the settlement of the Nagorno- Karabakh conflict, since the May 12, 1994, cease-fire, have failed to produce any tangible results. The key issues of contention pertain not only to the final status of Nagorno-Karabakh, but also to the methodology used to settle the conflict and the format of the negotiations. Whether Nagorno-Karabakh should directly par- ticipate in the negotiations, and if there should be a package or step-by-step solu- tion to the conflict, is crucial. Those issues have also become a matter of bitter political argument within Armenia and Azerbaijan, which impedes constructive dialogue. Currently, there is a lack of legitimacy and political will in both the Armenian and Azerbaijani leadership to solve the conflict, while Nagorno- Karabakh has been effectively left out of the negotiations. However, this should not dissuade international organizations from seeking a concrete solution, based on modern trends in international legal practices. Key words: Minsk Group, Nagorno-Karabakh, OSCE he Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, which mars relations between Armenia and TAzerbaijan and impedes the political stability and economic development of the South Caucasus, has a long history and deep roots. Its main political cause lies in the contradiction between the aspirations for national self-determination of the predominantly Armenian-populated enclave and Azerbaijan’s claim of ter- ritorial integrity to its Soviet-defined boundaries. Although the Bolsheviks grant- ed sovereignty over the overwhelmingly Armenian-populated oblast of Nagorno- Karabakh to Azerbaijan in 1921, the people of Nagorno-Karabakh have since questioned this decision. -

YOLUMUZ QARABAGADIR SON Eng.Qxd

CONTENTS Nationwide address of President Ilham Aliyev (27.09.2020) ..................4 A meeting of the Security Council chaired by President Ilham Aliyev ....9 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev in the "60 minutes" program on "Rossiya-1" TV channel ..........................................................................15 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Al Jazeera TV channel ..............21 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Al Arabiya TV channel ................35 Nationwide address of President Ilham Aliyev (04.10.2020) ..................38 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to TRT Haber TV channel ..............51 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Russian "Perviy Kanal" TV ........66 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to CNN-Tцrk Tv channel ................74 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Euronews TV channel ................87 Nationwide address of President Ilham Aliyev (09.10.2020) ..................92 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to CNN International TV channel's "The Connect World" program ................................................................99 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Sky News TV channel ................108 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Russian RBC TV channel ..........116 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Turkish Haber Global TV channel........................................................................129 Interview of President Ilham Aliyev to Turkish Haber Turk TV channel ..........................................................................140 -

Black Garden : Armenia and Azerbaijan Through Peace and War / Thomas De Waal

BLACK GARDEN THOMAS DE WAAL BLACK GARDEN Armenia and Azerbaijan through Peace and War a New York University Press • New York and London NEW YORK UNIVERSITY PRESS New York and London © 2003 by New York University All rights reserved Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data De Waal, Thomas. Black garden : Armenia and Azerbaijan through peace and war / Thomas de Waal. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-8147-1944-9 (cloth : alk. paper) 1. Nagorno-Karabakh Conflict, 1988–1994. 2. Armenia (Republic)— Relations—Azerbaijan. 3. Azerbaijan—Relations—Armenia (Republic) I. Title. DK699.N34 D4 2003 947.54085'4—dc21 2002153482 New York University Press books are printed on acid-free paper, and their binding materials are chosen for strength and durability. Manufactured in the United States of America 10987654321 War is kindled by the death of one man, or at most, a few; but it leads to the death of tremendous numbers. —Elias Canetti, Crowds and Power Mercy on the old master building a bridge, The passer-by may lay a stone to his foundation. I have sacrificed my soul, worn out my life, for the nation. A brother may arrange a rock upon my grave. —Sayat-Nova Contents Author’s Note ix Two Maps, of the South Caucasus and of Nagorny Karabakh xii–xiii. Introduction: Crossing the Line 1 1 February 1988: An Armenian Revolt 10 2 February 1988: Azerbaijan: Puzzlement and Pogroms 29 3 Shusha: The Neighbors’ Tale 45 4 1988–1989: An Armenian Crisis 55 5 Yerevan: Mysteries of the East 73 6 1988–1990: An Azerbaijani Tragedy 82 7