But Is It Art? Creative Writing Workshops in the U.S.* ( それにしても、文学と言えるのですか? アメリカにおけるクリエイティブ・ ライティングワークショップ)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 of 2020 to Understate It—2020 Was Not Square Books’ Best Year

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 OF 2020 To understate it—2020 was not Square Books’ best year. Like everyone, we struggled—but we are grateful to remain in business, and that all the booksellers here are healthy. When Covid19 arrived, our foot-traffic fell precipitously, and sales with it—2020 second-quarter sales were down 52% from those of the same period in 2019. But our many loyal customers adjusted along with us as we reopened operations when we were more confident of doing business safely. The sales trend improved in the third quarter, and November/December were only slightly down compared to those two months last year. We are immensely grateful to those of you who ordered online or by phone, allowing us to ship, deliver, or hold for curbside pickup, or who waited outside our doors to enter once our visitor count was at capacity. It is only through your abiding support that Square Books remains in business, ending the year down 30% and solid footing to face the continuing challenge of Covid in 2021. And there were some very good books published, of which one hundred bestsellers we’ll mention now. (By the way, we still have signed copies of many of these books; enquire accordingly.) Many books appear on this list every year—old favorites, if you will, including three William Faulkner books: Selected Short Stories (37th on our list) which we often recommend to WF novices, The Sound and the Fury (59) and As I Lay Dying (56), as well as a notably good new biography of Faulkner by Michael Gorra, The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War (61). -

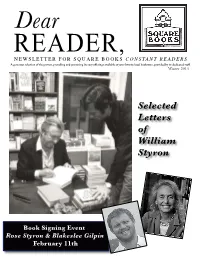

Selected Letters of William Styron

Dear Winter 2013 Selected Letters of William Styron Book Signing Event Rose Styron & Blakeslee Gilpin February 11th THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2012 With 2012 in rear view, we are very thankful for the many writers who came to us and the publishers who sent them to Square Books, as their books tend to dominate our bestseller list; some, like James Meek (The Heart Broke In, #30) and Lawrence Norfolk (John Saturnall’s Feast, #29), from as far as England – perhaps it’s the fascination with Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey (67) or J. K. Rowling’s Casual Vacancy (78). But as Dear Readers know, this list is usually crowded with those who live or have lived here, like Dean Wells’ Every Day by the Sun (22) or (long ago) James Meredith (A Mission From God, (10); William Faulkner’s Selected Stories (43), Ole Miss at Oxford, by Bill Morris (37), Mike Stewart’s Sporting Dogs and Retriever Training (39), John Brandon’s A Million Heavens (24), Airships (94), by Barry Hannah, Dream Cabinet by Ann Fisher-Wirth (87), Beginnings & Endings (85) by Ron Borne, Facing the Music (65) by Larry Brown, Neil White’s In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (35), the King twins’ Y’all Twins? (12), Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter Crooked Letter (13), The Fall of the House of Zeus (15) by Curtis Wilkie, Julie Cantrell’s Into the Free (16), Ole Miss Daily Devotions (18), and two perennial local favorites Wyatt Waters’ Oxford Sketchbook (36) and Square Table (8), which has been in our top ten ever since it was published; not to forget Sam Haskell and Promises I Made My Mother (6) or John Grisham, secure in the top two spots with The Racketeer and Calico Joe, nor our friend Richard Ford, with his great novel, Canada (5). -

Faulkner's Wake: the Emergence of Literary Oxford

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2004 Faulkner's Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford John Louis Fuller Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Fuller, John Louis, "Faulkner's Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford" (2004). Honors Theses. 2005. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2005 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faulkner’s Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford Bv John L. Fuller A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford April 2005 Advisor; Dr. Judson D. Wafson -7 ■ / ^—- Reader: Dr. Benjamin F. Fisher y. Reader: Dr. Andrew P. D^rffms Copyright © by John L. Fuller All Rights Reserved 1 For my parents Contents Abstract 5 I The Beginnings 9 (4Tell About the South 18 A Literary Awakening 25 II If You Build It, They Will Come 35 An Interview with Pochard Howorth 44Football, Faulkner, and Friends 57 An Interview with Barry Hannah Advancing Oxford’s Message 75 An Interview with Ann J. Abadie Oxford Tom 99 An Interview with Tom Franklin III Literary Grounds 117 Works cited 120 Abstract The genesis of this project was a commercial I saw on television advertising the University of Mississippi. “Is it the words that capture a place, or the place that captures the words?” noted actor and Mississippi native Morgan Freeman asked. -

Fall2011.Pdf

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Granta Fall 201 1 NOW AVAILABLE Complete and updated coverage by The New York Times about WikiLeaks and their controversial release of diplomatic cables and war logs OPEN SECRETS WikiLeaks, War, and American Diplomacy The New York Times Introduction by Bill Keller • Essential, unparalleled coverage A New York Times Best Seller from the expert writers at The New York Times on the hundreds he controversial antisecrecy organization WikiLeaks, led by Julian of thousands of confidential Assange, made headlines around the world when it released hundreds of documents revealed by WikiLeaks thousands of classified U.S. government documents in 2010. Allowed • Open Secrets also contains a T fascinating selection of original advance access, The New York Times sorted, searched, and analyzed these secret cables and war logs archives, placed them in context, and played a crucial role in breaking the WikiLeaks story. • online promotion at Open Secrets, originally published as an e-book, is the essential collection www.nytimes.com/opensecrets of the Times’s expert reporting and analysis, as well as the definitive chronicle of the documents’ release and the controversy that ensued. An introduction by Times executive editor, Bill Keller, details the paper’s cloak-and-dagger “We may look back at the war logs as relationship with a difficult source. Extended profiles of Assange and Bradley a herald of the end of America’s Manning, the Army private suspected of being his source, offer keen insight engagement in Afghanistan, just as into the main players. Collected news stories offer a broad and deep view into the Pentagon Papers are now a Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the messy challenges facing American power milestone in our slo-mo exit from in Europe, Russia, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. -

An Interview With

An Interview with DAVID ALAN GRIER, Ph.D. Conducted by Janet Abbate On 26 May 2015 Virginia Tech Blacksburg, Virginia IEEE Computer Society Copyright, IEEE Abbate: I’m talking with David Alan Grier on May 26, 2015. We are in the luxurious Virginia Tech conference room. I want to start with your education and early computing career. Grier: Okay. Abbate: You got a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Middleburg College in 1978. Grier: Yes. Abbate: Were you always interested in math? Is that sort of something you knew you wanted to do? Grier: No. I was sort of wavering between engineering and some form of computing, and Middlebury had neither. I chose the college because a lot of people around me, my family and teachers in high school, thought that I would be well matched for a liberal arts college. And when I got accepted they said far and away this is the best college you’ve gotten into; you should consider it. And so I chose it, and got there and discovered that they had one computer class, which I could have taught at that point, and as I drifted around and tried different things math seemed to be the best fit for me. There is a side of this that I did not realize at the time, that there is a fairly long tradition of math in my family, particularly my Mom’s mother, my grandmother; and that I was probably more immersed in the culture of it than I had thought. Abbate: Interesting. So you, as you’ve alluded to, already had some background in computing. -

Contributors' Notes

Yalobusha Review Volume 15 Article 37 5-1-2010 Contributors' Notes Journal Editors Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/yr Recommended Citation Editors, Journal (2010) "Contributors' Notes," Yalobusha Review: Vol. 15 , Article 37. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/yr/vol15/iss1/37 This Contributors' Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yalobusha Review by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editors: Contributors' Notes Contributors’ Notes Megan Abbot is the author of Die a Little (2005), The Song is You (2007), Queenpin (2008), and Bury Me Deep (2009), all published by Simon & Schuster; she has written a nonfiction study, The Street Was Mine: White Masculinity and Urban Space in Hardboiled Fiction and Film Noir (Palgrave MacMillan, 2002); and she is the editor of a female noir anthology, A Hell of a Woman (Busted Flush Press, 2008). Her short stories have appeared in Damn Near Dead: An Anthology of Geezer Noir (Busted Flush Press, 2006), Wall Street Noir (Akashic Books, 2007), Queens Noir (Akashic Books, 2007), and Detroit Noir (Akashic Books, 2007). Originally from Detroit, Michigan, Abbott earned her Ph.D. at New York University and currently lives in Queens, New York, with her husband, novelist Joshua Gaylord. Hal Ackerman has been on the faculty of the UCLA School of Theater, Film, and Television for the past twenty-four years and is currently co-area head of the screenwriting program. His book, Write Screenplays That Sell: The Ackerman Way (Tallfellow Press, 2003), is in its third printing and is the text of choice in a growing number of screenwriting programs around the country. -

Gordon Lish and His Influence Gordon Lish Is Perhaps Best Known As The

Gordon Lish and his Influence Gordon Lish is perhaps best known as the authoritative, and thus controversial, editor of Raymond Carver, among numerous other authors. This characterization however, does a grave injustice to the scope of Lish’s influence. Indeed, I would argue that no man has had a greater influence on the today’s literary landscape. A prolific author in his own right, Lish also served as editor, publisher, and teacher to some of the most significant voices of the latter‐half of the 20th century, as well as those of the 21st . With Lish, American publishing saw an unprecedented (and since unduplicated) output of challenging art by a major corporation, the occurrence of which came as direct result of one man’s artistic vision. It is these books, which Lish published, wrote, or otherwise influenced, which are the subject of my collection. In 1977, Gordon Lish left his position as Senior Editor of Esquire Magazine and accepted a job of the same title at Alfred A. Knopf. He worked at Knopf for eighteen years until parting ways in 1995, having assembled what is arguably one of the greatest editorial runs in the history of publishing. During these eighteen years Lish published many of the most memorable voices in contemporary fiction, many of whom he published for the first time. Among the authors who Lish brought into publication are: Raymond Carver, Don Delillo, Amy Hempel, Barry Hannah, Cynthia Ozick, Joy Williams, and Umass’s own, Noy Holland. What is perhaps most notable about Lish’s time at Knopf however, is the level of freedom he was given in determining what Knopf would publish. -

Graduate Course Descriptions Spring 2014

realist”) in conversations about the literature of the Global South. However, from its beginnings in Latin American literature, magical realism was Graduate Course rooted in an ontological claim—what Alejo Carpentier called the “marvelous real” (1949)—that foregrounded American particularity as the origin of an aesthetics and literature distinct from its European counterparts. What Carpentier pointed to was the limitations of realism as a narrative Descriptions mode in grappling with distinct geographic, cultural, historical, and political phenomena. Spring 2014 Following David Damrosch’s definition of “World Literature” as a reading practice and with Latin America as our starting point, this course will explore works written at the outer limits of “realism.” We will begin with a 617:01 Teaching College English return to debates surrounding the political function of realism and Fredric B. McClelland TH 6:00-8:30 Jameson’s essay on Third-World literature as national allegory and then Ext. 5500 [email protected] historicize the genealogy of magical realism in Latin American letters, before turning our attention to texts from Africa, South Asia, the Caribbean, The purpose of this course is to give an introduction to the teaching of and the United States. We will analyze the narrative ontologies offered by composition at the University of Mississippi. The course is not an these texts in their particular cultural and historical contexts as well as introduction to the history or theory of composition and rhetoric, nor is it a consider the political potential of a- or counter-realist narration more course in the principles of education theory. Rather, the course is structured broadly. -

New Southern Studies Graduate Students

the the newsletter of the Center for the study of southern Culture • fall 2010 the university of mississippi New Southern Studies Graduate Students David Wharton When this picture of the first-year graduate students was taken, on the Southern Studies orientation day in August, it had been raining. Hard. It had been raining and it was so hot out- side that the result was a day so mug- gy and oppressive that Professor David Wharton’s camera lens fogged up and the students stood around, shifting uncomfortably and talking earnestly about the weather while the lens took its sweet time clearing up. To think that was just three months ago. By now, midway into our first semes- ter, most of the nervous talk about the weather has dissipated. There are 13 new additions to the Southern Studies MA program this year, and among these there are but two men: Brian Wilson and Erik Watson. Brian is a native of Macon, Mississippi, and received his BA in political science and history from the New Southern Studies graduate students pictured at Barnard Observatory in August University of Mississippi. After six years 2010 are, left to right, front row: Amy Ulmer (Hendrix College), Camilla Aikin (Bard in Washington, D.C., working as an College), Eva Walton (Mercer University), Danielle St. Ours (Cornell University); sec- aide on Capitol Hill, he returned to pur- ond row: Kari Edwards (University of Tennessee, Chattanooga), Nell Knox (Millsaps sue his master’s in Southern Studies. He College), Erik Watson (Missouri Valley College); top row (left to right): Susie Penman hopes to go on to earn a PhD in history. -

CHRISTOPHER CHAMBERS 327 Bobet Hall Loyola University New Orleans New Orleans LA 70118 [email protected] 504.865.2475

CHRISTOPHER CHAMBERS 327 Bobet Hall Loyola University New Orleans New Orleans LA 70118 [email protected] 504.865.2475 EDUCATION Certificate in Literary Publishing, Emerson College 2014 MFA, Creative Writing (fiction), University of Alabama 1999 BS, English (Sociology minor), University of Wisconsin–River Falls 1984 EXPERIENCE Loyola University New Orleans 1999–present ADMINISTRATIVE APPOINTMENTS Director, Walker Percy Center for Writing & Publishing, 2014–present Chair, Department of English, 2012–2014 FACULTY APPOINTMENTS Professor of Creative Writing, 2011–present Associate Professor of Creative Writing, 2005–2011 Assitant Professor of Creative Writing, 1999–2005 University of Alabama, Tuscaloosa AL 1994-1999 Graduate Teaching Assistant, English Department Spanish River High School, Boca Raton, FL 1994 Teacher (English; physical education; industrial arts) Augsburg Publishing Company, Minneapolis, MN 1989–1992 Distribution Specialist, International Brotherhood of Teamsters Union Local 638 Freelance writer and editor, 1989-1995 Minneapolis, MN; Delray Beach, FL; Tuscaloosa, AL Independent commercial and residential construction contractor, 1984-1989 / 1992-1993 Minneapolis-St. Paul, MN Christopher Chambers 2 TEACHING COURSES TAUGHT Loyola University New Orleans. 1999– Writing About Literature Writing About Texts Introduction to Creative Writing Writing Fiction Feature Screenwriting I Feature Screenwriting II Writing the Short Script Creative Nonfiction Workshop Advanced Fiction Workshop Advanced Poetry Workshop Experimental Fiction Workshop Screenwriting: Adaptation Flash Fiction and Prose Poetry Autobiography Editing and Publishing Xavier University (New Orleans, LA) 2002 Feature Screenwriting University of Alabama (Tuscaloosa, AL) 1994-1999 Freshman Composition: Rhetoric Freshman Composition: Writing About Literature Introduction to Creative Writing Advanced Fiction Writing Tuscaloosa Council for the Arts (Tuscaloosa, AL) 1996 Writers in the Schools Program: Poetry for Children HONORS THESES DIRECTED 2014-2015. -

Oral Tradition 22.1

Oral Tradition, 22/1 (2007): 14-29 Dylan and the Nobel Gordon Ball Allow me to begin on a personal note. I’m not a Dylan expert, nor a scholar of music, or classics, or folklore, or, for that matter, the Nobel Prize. My specialty is the poet Allen Ginsberg and the literature of the Beat Generation; I edited three books with Ginsberg and have taken and exhibited a number of photographs of the poet and his Beat colleagues over the years. For decades I’ve admired the work of Bob Dylan, whom I saw at Newport 1965; my memoir ‘66 Frames relates my first contact with his music, and he makes a brief appearance in a recently completed chronicle of my years on an upstate New York farm with Ginsberg and other Beats. In 1996 I first wrote the Nobel Committee of the Swedish Academy, nominating Dylan for its Prize in literature. The idea to do so did not originate with me but with two Dylan afficianados in Norway, journalist Reidar Indrebø and attorney Gunnar Lunde. (Also, a number of other professors have supported Dylan’s candidacy at various times in the past.) Mr. Indrebø and Mr. Lunde had written Allen Ginsberg seeking help with the nomination. (The nominator must be a member of the Swedish Academy, or professor of literature or language, or a past laureate in literature, or the president of a national writers’ organization.) Ginsberg’s office called and asked if I would like to write a nominating letter. In my 1996 nomination, I cited the almost unlimited dimensions of Dylan’s work, how it has permeated the globe and affected history. -

Short Presentation Research Outputs

Martyn Richard Bone Associate Professor Department of English, Germanic and Romance Studies Postal address: Emil Holms Kanal 6, 2300 København S, KUA1 24.3.57 Email: [email protected] Mobile: +45 60 62 46 53 Phone: +45 35 32 85 96 Web address: http://www.engerom.ku.dk Web: http://www.engerom.ku.dk Short presentation Martyn Bone, associate professor of American literature My main research areas are the literature and culture of the U.S. South, African American literature, and transnational American studies. I teach a range of courses in American literature, African American literature, U.S. southern literature, American studies, and U.S. popular music. I am the author of Where the New World Is: Literature about the U.S. South at Global Scales (University of Georgia Press, 2018) and The Postsouthern Sense of Place in Contemporary Fiction (Louisiana State University Press, 2005). I am the editor of Perspectives on Barry Hannah (University Press of Mississippi, 2007) and coeditor of the University Press of Florida mini-series Creating Citizenship in the Nineteenth-Century South (2013); The American South in the Atlantic World (2013); and Creating and Consuming the American South (2015). I have contributed to numerous books including A History of the Literature of the U.S. South (Cambridge University Press, 2021), The Oxford Handbook of the Literature of the U.S. South (Oxford University Press, 2016), the New Cambridge Companion to William Faulkner (Cambridge University Press, 2015), and the Cambridge Companion to American Fiction after 1945 (Cambridge University Press, 2011). My articles have appeared in American Literature, Journal of American Studies, CR: New Centennial Review, African American Review, and other journals.