Gordon Lish and His Influence Gordon Lish Is Perhaps Best Known As The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 of 2020 to Understate It—2020 Was Not Square Books’ Best Year

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 OF 2020 To understate it—2020 was not Square Books’ best year. Like everyone, we struggled—but we are grateful to remain in business, and that all the booksellers here are healthy. When Covid19 arrived, our foot-traffic fell precipitously, and sales with it—2020 second-quarter sales were down 52% from those of the same period in 2019. But our many loyal customers adjusted along with us as we reopened operations when we were more confident of doing business safely. The sales trend improved in the third quarter, and November/December were only slightly down compared to those two months last year. We are immensely grateful to those of you who ordered online or by phone, allowing us to ship, deliver, or hold for curbside pickup, or who waited outside our doors to enter once our visitor count was at capacity. It is only through your abiding support that Square Books remains in business, ending the year down 30% and solid footing to face the continuing challenge of Covid in 2021. And there were some very good books published, of which one hundred bestsellers we’ll mention now. (By the way, we still have signed copies of many of these books; enquire accordingly.) Many books appear on this list every year—old favorites, if you will, including three William Faulkner books: Selected Short Stories (37th on our list) which we often recommend to WF novices, The Sound and the Fury (59) and As I Lay Dying (56), as well as a notably good new biography of Faulkner by Michael Gorra, The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War (61). -

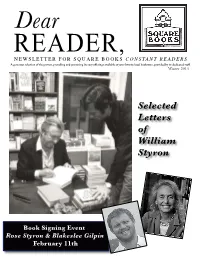

Selected Letters of William Styron

Dear Winter 2013 Selected Letters of William Styron Book Signing Event Rose Styron & Blakeslee Gilpin February 11th THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2012 With 2012 in rear view, we are very thankful for the many writers who came to us and the publishers who sent them to Square Books, as their books tend to dominate our bestseller list; some, like James Meek (The Heart Broke In, #30) and Lawrence Norfolk (John Saturnall’s Feast, #29), from as far as England – perhaps it’s the fascination with Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey (67) or J. K. Rowling’s Casual Vacancy (78). But as Dear Readers know, this list is usually crowded with those who live or have lived here, like Dean Wells’ Every Day by the Sun (22) or (long ago) James Meredith (A Mission From God, (10); William Faulkner’s Selected Stories (43), Ole Miss at Oxford, by Bill Morris (37), Mike Stewart’s Sporting Dogs and Retriever Training (39), John Brandon’s A Million Heavens (24), Airships (94), by Barry Hannah, Dream Cabinet by Ann Fisher-Wirth (87), Beginnings & Endings (85) by Ron Borne, Facing the Music (65) by Larry Brown, Neil White’s In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (35), the King twins’ Y’all Twins? (12), Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter Crooked Letter (13), The Fall of the House of Zeus (15) by Curtis Wilkie, Julie Cantrell’s Into the Free (16), Ole Miss Daily Devotions (18), and two perennial local favorites Wyatt Waters’ Oxford Sketchbook (36) and Square Table (8), which has been in our top ten ever since it was published; not to forget Sam Haskell and Promises I Made My Mother (6) or John Grisham, secure in the top two spots with The Racketeer and Calico Joe, nor our friend Richard Ford, with his great novel, Canada (5). -

B E N N I N G T O N W R I T I N G S E M I N A

MFAW PUBLIC SCHEDULE June 15–24, 2017 NOTE: Schedule subject to change All faculty, guest, and graduate lectures and readings will be held in Tishman Lecture Hall, unless otherwise indicated. All evening Faculty and Guest Readings will be held in the Deane Carriage Barn. Thursday, June 15 7:00 Faculty & Guest Readings: Kaitlyn Greenidge and Amy Hempel Friday, June 16 Graduate Readings 4:00 Alexander Benaim 4:20 Andrea Caswell 4:40 Michael Connor 7:00 Faculty & Guest Readings: Benjamin Anastas and Mark Wunderlich 8:00 Historical Presentation: Lynne Sharon Schwartz: “Historic Recordings of Great 20th Century American Authors Reading their Work.” Deane Carriage Barn Saturday, June 17 Graduate Lectures 8:20 Ashley Olsen: “50 Shades of Consent: Sexual Desire and Sexual Violence in Contemporary Short Stories.” This lecture will examine tests from contemporary female authors including Mary Gaitskill, Margaret Atwood, and Roxane Gay. 9:00 Katie Pryor: “Persona & Violence in Ai’s Cruelty & Iliana Rocha’s Karankawa.” Both of these poets use persona poems to explore violence. What is powerful about this poetic device? How does the persona poem involve the reader and interrogate our notions of self? We’ll explore the connections and differences between these poets and their first books. 9:40 Karen Rile: “The Bad Writing Competition: Introducing Narrative Distance to Undergraduates.” A technique-centered workshop that offers coordinated readings and prompts can help beginning writers focus on discrete, achievable goals. But demonstrating smooth narrative distance shifts presents a practical challenge in an undergraduate workshop setting. The Bad Writing Competition, or mastery through parody, is a deft solution—with some unexpected ancillary benefits. -

Faulkner's Wake: the Emergence of Literary Oxford

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2004 Faulkner's Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford John Louis Fuller Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Fuller, John Louis, "Faulkner's Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford" (2004). Honors Theses. 2005. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2005 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faulkner’s Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford Bv John L. Fuller A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford April 2005 Advisor; Dr. Judson D. Wafson -7 ■ / ^—- Reader: Dr. Benjamin F. Fisher y. Reader: Dr. Andrew P. D^rffms Copyright © by John L. Fuller All Rights Reserved 1 For my parents Contents Abstract 5 I The Beginnings 9 (4Tell About the South 18 A Literary Awakening 25 II If You Build It, They Will Come 35 An Interview with Pochard Howorth 44Football, Faulkner, and Friends 57 An Interview with Barry Hannah Advancing Oxford’s Message 75 An Interview with Ann J. Abadie Oxford Tom 99 An Interview with Tom Franklin III Literary Grounds 117 Works cited 120 Abstract The genesis of this project was a commercial I saw on television advertising the University of Mississippi. “Is it the words that capture a place, or the place that captures the words?” noted actor and Mississippi native Morgan Freeman asked. -

Fall2011.Pdf

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Granta Fall 201 1 NOW AVAILABLE Complete and updated coverage by The New York Times about WikiLeaks and their controversial release of diplomatic cables and war logs OPEN SECRETS WikiLeaks, War, and American Diplomacy The New York Times Introduction by Bill Keller • Essential, unparalleled coverage A New York Times Best Seller from the expert writers at The New York Times on the hundreds he controversial antisecrecy organization WikiLeaks, led by Julian of thousands of confidential Assange, made headlines around the world when it released hundreds of documents revealed by WikiLeaks thousands of classified U.S. government documents in 2010. Allowed • Open Secrets also contains a T fascinating selection of original advance access, The New York Times sorted, searched, and analyzed these secret cables and war logs archives, placed them in context, and played a crucial role in breaking the WikiLeaks story. • online promotion at Open Secrets, originally published as an e-book, is the essential collection www.nytimes.com/opensecrets of the Times’s expert reporting and analysis, as well as the definitive chronicle of the documents’ release and the controversy that ensued. An introduction by Times executive editor, Bill Keller, details the paper’s cloak-and-dagger “We may look back at the war logs as relationship with a difficult source. Extended profiles of Assange and Bradley a herald of the end of America’s Manning, the Army private suspected of being his source, offer keen insight engagement in Afghanistan, just as into the main players. Collected news stories offer a broad and deep view into the Pentagon Papers are now a Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the messy challenges facing American power milestone in our slo-mo exit from in Europe, Russia, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. -

Description & Detail

CLOSE-UP: DE SCRIPTION AND DETAIL Glimmer Train Close-ups are single-topic, e-doc publications specifically for writers, from the editors of Glimmer Train Stories and Writers Ask. MYLA GOLDBERG, interviewed by Sarah Anne Johnson: In each novel, there are many details that are fact, and others that are based on fact, and still others that are invented. When is it important to use actual details, and when does the imaginative work to better effect? There’s not one answer to that question. Every story, every novel will dic- tate its own answers to questions of research. When you’re writing fiction, you don’t ever have to use anything real if you don’t want to, but it’s a lot easier. If you’re trying to create a convincing setting, you want to start with reality. You can’t start from scratch because that’s impossible. Given that that’s the case, you use research to give yourself enough of the real-world fabric to get yourself in there. In the case of Wickett’s Remedy, I used research until I could look and see things without using research anymore. Research at first was a men- tal tool to help me inhabit that time period and those people. If there were details that stuck out or grabbed me and I realized that I couldn’t do any better than that, I used them. Often the world is going to supply you with better things than you’ll Submission Calendar CLOSE-UP: DESCRIPTION & DETAIL, 2nd ed. © Glimmer Train Press • glimmertrain.org 1 1 be able to come up with anyway. -

Evalyn Lee Is a Former CBS News Producer Who Lives in London with Her Husband and Two Children

Tyler Atwood comes from a long line of subsistence farmers but knows very little about the planting or harvesting of crops. He is the author of one collection of poetry, an electric sheep jumps to greener pasture (University of Hell Press, 2014). His poems appear in or are forthcoming from Gravel, mojo, Columbia Poetry Review, Hobart, The Offbeat, Profane Journal, Word Riot, and elsewhere. He lives and works in Denver, Colorado. Tim Barzditis is a poetry student of George Mason University’s Creative Writing MFA program. Prior to his time at GMU, Tim earned his BA and MA in English at Lynchburg College. He currently serves as the Comics Editor for Hellscape Press. He is also involved as a reader for So To Speak, Phoebe, as and Stillhouse Press. Tim’s work has been recently featured in Foothill: a journal of poetry, Whurk, Freezeray Poetry, Five:2:One Magazine, and elsewhere. Joe Baumann writes works of fiction and essays that appear in Zone 3, Hawai’i Review, Eleven Eleven, and elsewhere. He is the author of Ivory Children, published in 2013 by Red Bird Chapbooks. He possesses a PhD in English from the University of Louisiana-Lafayette and teaches composition, creative writing, and literature at St. Charles Community College in Cottleville, Missouri. He has been nominated for three Pushcart Prizes and was recently nominated for inclusion in Best American Short Stories 2016. Shanelle Galloway Calvert started writing down stories as soon as she knew how to hold a pencil, but before she even knew she wanted to be a writer. -

Bear River Writers’ Conference Writers’ River Bear the of Support

Find your place at Bear River Bear at place your Find www.lsa.umich.edu/bearriver HEMPEL Y AM For more information or to download a registration form, please visit our website. website. our visit please form, registration a download to or information more For uest G Special Special James Cyan photosby imagefrom Chen;Background photo:Kenneth Hempel Amy refunded upon request if you do not wish to enroll in an alternate workshop. alternate an in enroll to wish not do you if request upon refunded themselves and their words. words. their and themselves first serve basis. In the unlikely event of a workshop cancellation, your entire payment will be be will payment entire your cancellation, workshop a of event unlikely the In basis. serve first it offers community members a hiatus from daily routine and the chance to find a space for for space a find to chance the and routine daily from hiatus a members community offers it Workshops will be assigned on a first come come first a on assigned be will Workshops Register early to secure your workshop choice: workshop your secure to early Register participants and faculty. and participants natural and creative worlds. Populated by an eclectic collection of writers of all levels of experience, experience, of levels all of writers of collection eclectic an by Populated worlds. creative and natural northern Michigan is not simply backdrop for the session, but inspiration for the creative work of of work creative the for inspiration but session, the for backdrop simply not is Michigan northern Monday, is defined by its own particular geography, situated as it is at the intersection of the the of intersection the at is it as situated geography, particular own its by defined is Monday, conference for those who prefer greater privacy: $575 per person per $575 privacy: greater prefer who those for conference writing. -

An Interview With

An Interview with DAVID ALAN GRIER, Ph.D. Conducted by Janet Abbate On 26 May 2015 Virginia Tech Blacksburg, Virginia IEEE Computer Society Copyright, IEEE Abbate: I’m talking with David Alan Grier on May 26, 2015. We are in the luxurious Virginia Tech conference room. I want to start with your education and early computing career. Grier: Okay. Abbate: You got a bachelor’s degree in mathematics from Middleburg College in 1978. Grier: Yes. Abbate: Were you always interested in math? Is that sort of something you knew you wanted to do? Grier: No. I was sort of wavering between engineering and some form of computing, and Middlebury had neither. I chose the college because a lot of people around me, my family and teachers in high school, thought that I would be well matched for a liberal arts college. And when I got accepted they said far and away this is the best college you’ve gotten into; you should consider it. And so I chose it, and got there and discovered that they had one computer class, which I could have taught at that point, and as I drifted around and tried different things math seemed to be the best fit for me. There is a side of this that I did not realize at the time, that there is a fairly long tradition of math in my family, particularly my Mom’s mother, my grandmother; and that I was probably more immersed in the culture of it than I had thought. Abbate: Interesting. So you, as you’ve alluded to, already had some background in computing. -

Contributors' Notes

Yalobusha Review Volume 15 Article 37 5-1-2010 Contributors' Notes Journal Editors Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/yr Recommended Citation Editors, Journal (2010) "Contributors' Notes," Yalobusha Review: Vol. 15 , Article 37. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/yr/vol15/iss1/37 This Contributors' Notes is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Yalobusha Review by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Editors: Contributors' Notes Contributors’ Notes Megan Abbot is the author of Die a Little (2005), The Song is You (2007), Queenpin (2008), and Bury Me Deep (2009), all published by Simon & Schuster; she has written a nonfiction study, The Street Was Mine: White Masculinity and Urban Space in Hardboiled Fiction and Film Noir (Palgrave MacMillan, 2002); and she is the editor of a female noir anthology, A Hell of a Woman (Busted Flush Press, 2008). Her short stories have appeared in Damn Near Dead: An Anthology of Geezer Noir (Busted Flush Press, 2006), Wall Street Noir (Akashic Books, 2007), Queens Noir (Akashic Books, 2007), and Detroit Noir (Akashic Books, 2007). Originally from Detroit, Michigan, Abbott earned her Ph.D. at New York University and currently lives in Queens, New York, with her husband, novelist Joshua Gaylord. Hal Ackerman has been on the faculty of the UCLA School of Theater, Film, and Television for the past twenty-four years and is currently co-area head of the screenwriting program. His book, Write Screenplays That Sell: The Ackerman Way (Tallfellow Press, 2003), is in its third printing and is the text of choice in a growing number of screenwriting programs around the country. -

Il Miglior Fabbro?

The Raymond Carver Review 1 Il Miglior Fabbro? On Gordon Lish’s Editing of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love Enrico Monti, University of Bologna, Italy 1. Introduction In April 1981, when What We Talk About When We Talk About Love appeared, Raymond Carver was still little known to wider audiences and few could predict that he was soon to be acclaimed as the “American Chekhov” and the father of literary Minimalism. Yet, those seventeen short fragments managed to reinvigorate the realistic trend of the short-story with their spare and laconic portrait of small-town America: a portrait free of condescendence, irony, or denunciation, yet full of hopeless desolation. That collection’s pared-down narrative has come to represent for many readers Raymond Carver’s stylistic trademark, although it undeniably marks a “minimalistic” peak in his career, and a point of no return.1 It is precisely in relation to that minimalism that we shall reconsider the role played in the collection’s final output by Gordon Lish, Carver’s longtime editor and friend. To do so, we shall analyze the scope and the extent of Lish’s editorial work on the collection, as it is now visible in the archives of the Lilly Library at Indiana University.2 2. Lish and Carver A flamboyant fiction editor at Esquire (1969-76), McGraw-Hill (1976-1977) and Knopf (1977-1990) and a writer himself, Gordon Lish acquired a reputation in the 70s as a provocative, brilliant talent scout, “at the epicenter of American literary publishing” (Birkerts 252). -

Download for Personal Use Only

Durham Research Online Deposited in DRO: 08 September 2017 Version of attached le: Accepted Version Peer-review status of attached le: Peer-reviewed Citation for published item: Botha, Marc (2016) 'Microction.', in The Cambridge companion to the English short story. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 201-220. Cambridge companions to literature. Further information on publisher's website: https://doi.org/10.1017/CCO9781316018866.016 Publisher's copyright statement: This material has been published in The Cambridge Companion to the English Short Story edited by Ann-Marie Einhaus. This version is free to view and download for personal use only. Not for re-distribution, re-sale or use in derivative works. c Cambridge University Press. Additional information: Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in DRO • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full DRO policy for further details. Durham University Library, Stockton Road, Durham DH1 3LY, United Kingdom Tel : +44 (0)191 334 3042 | Fax : +44 (0)191 334 2971 https://dro.dur.ac.uk CAMBRIDGE COMPANION TO THE ENGLIGH SHORT STORY Ed. Ann-Marie Einhaus; forthcoming 2016 Chapter 14 Microfiction Marc Botha 1. A Brief History of Very Short Fiction 1.1 Now! “The short story form, in its brevity and condensation, fits our age”, writes Michèle Roberts in her aptly brief introduction to Deborah Levy’s collection Black Vodka (2013).