Faulkner's Wake: the Emergence of Literary Oxford

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Smithfield Review, Volume 20, 2016

In this issue — On 2 January 1869, Olin and Preston Institute officially became Preston and Olin Institute when Judge Robert M. Hudson of the 14th Circuit Court issued a charter Includes Ten Year Index for the school, designating the new name and giving it “collegiate powers.” — page 1 The On June 12, 1919, the VPI Board of Visitors unanimously elected Julian A. Burruss to succeed Joseph D. Eggleston as president of the Blacksburg, Virginia Smithfield Review institution. As Burruss began his tenure, veterans were returning from World War I, and America had begun to move toward a post-war world. Federal programs Studies in the history of the region west of the Blue Ridge for veterans gained wide support. The Nineteenth Amendment, giving women Volume 20, 2016 suffrage, gained ratification. — page 27 A Note from the Editors ........................................................................v According to Virginia Tech historian Duncan Lyle Kinnear, “he [Conrad] seemed Olin and Preston Institute and Preston and Olin Institute: The Early to have entered upon his task with great enthusiasm. Possessed as he was with a flair Years of Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University: Part II for writing and a ‘tongue for speaking,’ this ex-confederate secret agent brought Clara B. Cox ..................................................................................1 a new dimension of excitement to the school and to the town of Blacksburg.” — page 47 Change Amidst Tradition: The First Two Years of the Burruss Administration at VPI “The Indian Road as agreed to at Lancaster, June the 30th, 1744. The present Faith Skiles .......................................................................................27 Waggon Road from Cohongoronto above Sherrando River, through the Counties of Frederick and Augusta . -

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 of 2020 to Understate It—2020 Was Not Square Books’ Best Year

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 OF 2020 To understate it—2020 was not Square Books’ best year. Like everyone, we struggled—but we are grateful to remain in business, and that all the booksellers here are healthy. When Covid19 arrived, our foot-traffic fell precipitously, and sales with it—2020 second-quarter sales were down 52% from those of the same period in 2019. But our many loyal customers adjusted along with us as we reopened operations when we were more confident of doing business safely. The sales trend improved in the third quarter, and November/December were only slightly down compared to those two months last year. We are immensely grateful to those of you who ordered online or by phone, allowing us to ship, deliver, or hold for curbside pickup, or who waited outside our doors to enter once our visitor count was at capacity. It is only through your abiding support that Square Books remains in business, ending the year down 30% and solid footing to face the continuing challenge of Covid in 2021. And there were some very good books published, of which one hundred bestsellers we’ll mention now. (By the way, we still have signed copies of many of these books; enquire accordingly.) Many books appear on this list every year—old favorites, if you will, including three William Faulkner books: Selected Short Stories (37th on our list) which we often recommend to WF novices, The Sound and the Fury (59) and As I Lay Dying (56), as well as a notably good new biography of Faulkner by Michael Gorra, The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War (61). -

The Retail Sector on Long Island Overlooked… Undervalued… Essential!

The Retail Sector on Long Island Overlooked… Undervalued… Essential! A Preliminary Report from the Long Island Business Council May 2021 Long Island “ L I ” The Sign of Success 2 | The Retail Sector on Long Island: Overlooked, Undervalued, Essential! Long Island Business Council Mission Statement The Long Island Business Council (LIBC) is a collaborative organization working to advocate for and assist the business community and related stakeholders. LIBC will create an open dialogue with key stakeholder groups and individuals to foster solutions to regional and local economic challenges. LIBC will serve as a community-focused enterprise that will work with strategic partners in government, business, education, nonprofit and civic sectors to foster a vibrant business climate, sustainable economic growth and an inclusive and shared prosperity that advances business attraction, creation, retention and expansion; and enhances: • Access to relevant markets (local, regional, national, global); • Access to a qualified workforce (credentialed workforce; responsive education & training); • Access to business/economic resources; • Access to and expansion of the regional supply chain; • A culture of innovation; • Commitment to best practices and ethical operations; • Adaptability, resiliency and diversity of regional markets to respond to emerging trends; • Navigability of the regulatory environment; • Availability of supportive infrastructure; • An attractive regional quality of life © 2021 LONG ISLAND BUSINESS COUNCIL (516) 794-2510 [email protected] -

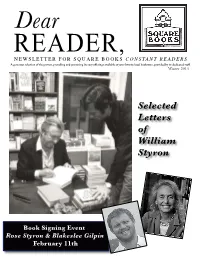

Selected Letters of William Styron

Dear Winter 2013 Selected Letters of William Styron Book Signing Event Rose Styron & Blakeslee Gilpin February 11th THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2012 With 2012 in rear view, we are very thankful for the many writers who came to us and the publishers who sent them to Square Books, as their books tend to dominate our bestseller list; some, like James Meek (The Heart Broke In, #30) and Lawrence Norfolk (John Saturnall’s Feast, #29), from as far as England – perhaps it’s the fascination with Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey (67) or J. K. Rowling’s Casual Vacancy (78). But as Dear Readers know, this list is usually crowded with those who live or have lived here, like Dean Wells’ Every Day by the Sun (22) or (long ago) James Meredith (A Mission From God, (10); William Faulkner’s Selected Stories (43), Ole Miss at Oxford, by Bill Morris (37), Mike Stewart’s Sporting Dogs and Retriever Training (39), John Brandon’s A Million Heavens (24), Airships (94), by Barry Hannah, Dream Cabinet by Ann Fisher-Wirth (87), Beginnings & Endings (85) by Ron Borne, Facing the Music (65) by Larry Brown, Neil White’s In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (35), the King twins’ Y’all Twins? (12), Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter Crooked Letter (13), The Fall of the House of Zeus (15) by Curtis Wilkie, Julie Cantrell’s Into the Free (16), Ole Miss Daily Devotions (18), and two perennial local favorites Wyatt Waters’ Oxford Sketchbook (36) and Square Table (8), which has been in our top ten ever since it was published; not to forget Sam Haskell and Promises I Made My Mother (6) or John Grisham, secure in the top two spots with The Racketeer and Calico Joe, nor our friend Richard Ford, with his great novel, Canada (5). -

Fall2011.Pdf

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Granta Fall 201 1 NOW AVAILABLE Complete and updated coverage by The New York Times about WikiLeaks and their controversial release of diplomatic cables and war logs OPEN SECRETS WikiLeaks, War, and American Diplomacy The New York Times Introduction by Bill Keller • Essential, unparalleled coverage A New York Times Best Seller from the expert writers at The New York Times on the hundreds he controversial antisecrecy organization WikiLeaks, led by Julian of thousands of confidential Assange, made headlines around the world when it released hundreds of documents revealed by WikiLeaks thousands of classified U.S. government documents in 2010. Allowed • Open Secrets also contains a T fascinating selection of original advance access, The New York Times sorted, searched, and analyzed these secret cables and war logs archives, placed them in context, and played a crucial role in breaking the WikiLeaks story. • online promotion at Open Secrets, originally published as an e-book, is the essential collection www.nytimes.com/opensecrets of the Times’s expert reporting and analysis, as well as the definitive chronicle of the documents’ release and the controversy that ensued. An introduction by Times executive editor, Bill Keller, details the paper’s cloak-and-dagger “We may look back at the war logs as relationship with a difficult source. Extended profiles of Assange and Bradley a herald of the end of America’s Manning, the Army private suspected of being his source, offer keen insight engagement in Afghanistan, just as into the main players. Collected news stories offer a broad and deep view into the Pentagon Papers are now a Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the messy challenges facing American power milestone in our slo-mo exit from in Europe, Russia, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. -

John Coward on in Search of Willie Morris: the Mercurial Life Of

Larry L King. In Search of Willie Morris: The Mercurial Life of a Legendary Writer and Editor. New York: PublicAffairs, 2006. 353 pp. $26.95, cloth, ISBN 978-1-58648-384-5. Reviewed by John M. Coward Published on Jhistory (July, 2007) When Willie Morris ascended to the editor's For a glorious cultural moment, Harper's and its desk at Harper's in 1967, he was perhaps the brilliant young editor were the talk of New York brightest star in American magazine journalism. publishing. Morris dined at Elaine's and partied At thirty-two, he was the youngest editor in the with the likes of Lauren Bacall, Leonard Bern‐ magazine's 117-year history--and perhaps its most stein, and Mickey Mantle. Larry L. King tells of audacious. A small-town Mississippi boy of prodi‐ one Manhattan party where Senator Ted Kennedy gious literary talent, Morris was also a painfully mistook the shirt-sleeved Harper's editor for a complex man ill-suited to the editor's chair. In the bartender and asked him for a scotch and soda. first place, he was an individualist in a business Morris complied--prompting a Kennedy apology that required teamwork. He hated meetings. He once the laughing stopped. avoided office correspondence. Morris was also Larry L. King, Morris's long-time friend (and an inveterate raconteur, far too fond of the bottle occasional antagonist), tells these stories and to become a stalwart of the magazine industry. more in this clear-eyed biography of Willie Mor‐ But Morris loved Harper's and he was deter‐ ris, a magazine editor who in many ways embod‐ mined to re-energize the venerable publication. -

Scrip Order Form

St. Thomas Aquinas SCRIP ORDER FORM Thank you! Your support is greatly appreciated! Please remember that we can sell only the amounts listed on the order form. Name:_______________________________________________Phone:___________________Date:_______________ Check# :_________________Amount:__________________ * Please make checks payable to: St. Thomas Aquinas * Filled by__________NEEDS:________________________________________________________________________ Retailer Profit Card Qty. Total Retailer Profit Card Qty. Total (c.o.a.) = certificate on account for Amount (c.o.a.) = certificate on for Amount school account school $5.00 $100 Claire’s $0.90 $10 All Seasons Gutter/New All Seasons Gutter/Topper $10.00 $100 Cold Stone $0.80 $10 Creamery American Eagle Outfitters $2.00 $25 Courtyard/Marriott $6.00 $50 Applebees $2.00 $25 Critter $0.50 $10 Nation(Dyvig’s) Arby’s $0.80 $10 Barnes & Noble/B. Dalton $1.00 $10 Derry Auto (c.o.a.) $1.00 $25 Barnes & Noble/B. Dalton $2.50 $25 Derry Auto (c.o.a.) $2.50 $50 Bath and Body Works $1.30 $10 Derry Auto (c.o.a.) $5.00 $100 Bath and Body Works $3.25 $25 Dillard’s $2.25 $25 Bed, Bath and Beyond $1.75 $25 Dress Barn $2.00 $25 Best Buy $0.50 $25 Express $2.50 $25 Best Buy $2.00 $100 Fareway $0.50 $25 Big Time Cinema (Fridley’s) $1.00 $10 Fareway $1.00 $50 Borders/Waldenbooks $0.90 $10 Fareway $2.00 $100 Borders/Waldenbooks $2.25 $25 Fairfield Inn/Marriott $6.00 $50 Build-A-Bear $2.00 $25 Fazoli’s $1.75 $25 Burger King $0.50 $10 Finish Line $2.50 $25 Cabela’s $3.25 $25 Flower Cart (c.o.a.) $1.25 $25 Carlos O’Kelly $0.90 $10 Foot Locker $2.25 $25 Casey’s $0.30 $10 Fuhs Pastry $1.00 $10 Casey’s $0.75 $25 Gap/Old $2.25 $25 Navy/Banana Republic Casey’s $1.50 $50 GameStop $0.75 $25 Cheesecake Factory $1.25 $25 Gerber’s (c.o.a.) $2.50 $50 Chili’s/Macaroni Grill/On the $2.75 $25 Gerber’s (c.o.a.) $5.00 $100 Boarder Chuck E. -

We Help Our Friends Grow We Want to Help You Make More Meaningful Connections Through: PRINT Online • Social Media Partnerships • Email Marketing

2021 Media Kit Inspirational Art, Crafts & Lifestyle Magazines We Help Our Friends Grow We want to help you make more meaningful connections through: PRINT Online • Social Media Partnerships • Email Marketing A Somerset Holiday Art Journaling Art Quilting Studio Belle Armoire Jewelry GreenCraft In Her Studio Mingle Somerset Studio Willow and Sage & Special Editions 2 About the Publisher When it comes to the art of crafting, no one does it better than Stampington & Company. — Mr. Magazine™ Samir Husni Since 1994, Stampington & Company has been a Leading Source of Information and Inspiration for Artists and Crafts Lovers, Storytellers, and Photographers Around the World Known for its stunning full-color photography and step-by-step instructions, the company’s magazines provide a forum for both professional artists and hobbyists looking to share their beautiful handmade creations, tips, and techniques with one another. Our community loves to immerse themselves in our magazines. These magazines are meant to be curled up with, kept in libraries as a resource to reference, and to share years later with friends and family. The enthusiasm of our readers doesn’t end here. Our community loves to blog and post pictures across social media from a wide range of channels, showing off our exclusive stories and soul-stirring photography. Our Social Profile 100K+ Facebook fans 94K+ Instagram followers 2.7m Pinterest monthly viewers 25K+ Twitter followers Media Kit 3 What’s Inside This media kit contains a wealth of information. Take a moment to read each of our publication descriptions and audience information to find the perfect advertising venue for your products. -

1 the Eugene D. Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese Library

The Eugene D. Genovese and Elizabeth Fox-Genovese Library Bibliography: with Annotations on marginalia, and condition. Compiled by Christian Goodwillie, 2017. Coastal Affair. Chapel Hill, NC: Institute for Southern Studies, 1982. Common Knowledge. Duke Univ. Press. Holdings: vol. 14, no. 1 (Winter 2008). Contains: "Elizabeth Fox-Genovese: First and Lasting Impressions" by Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham. Confederate Veteran Magazine. Harrisburg, PA: National Historical Society. Holdings: vol. 1, 1893 only. Continuity: A Journal of History. (1980-2003). Holdings: Number Nine, Fall, 1984, "Recovering Southern History." DeBow's Review and Industrial Resources, Statistics, etc. (1853-1864). Holdings: Volume 26 (1859), 28 (1860). Both volumes: Front flyleaf: Notes OK Both volumes badly water damaged, replace. Encyclopedia of Southern Baptists. Nashville: Broadman Press, 1958. Volumes 1 through 4: Front flyleaf: Notes OK Volume 2 Text block: scattered markings. Entrepasados: Revista De Historia. (1991-2012). 1 Holdings: number 8. Includes:"Entrevista a Eugene Genovese." Explorations in Economic History. (1969). Holdings: Vol. 4, no. 5 (October 1975). Contains three articles on slavery: Richard Sutch, "The Treatment Received by American Slaves: A Critical Review of the Evidence Presented in Time on the Cross"; Gavin Wright, "Slavery and the Cotton Boom"; and Richard K. Vedder, "The Slave Exploitation (Expropriation) Rate." Text block: scattered markings. Explorations in Economic History. Academic Press. Holdings: vol. 13, no. 1 (January 1976). Five Black Lives; the Autobiographies of Venture Smith, James Mars, William Grimes, the Rev. G.W. Offley, [and] James L. Smith. Documents of Black Connecticut; Variation: Documents of Black Connecticut. 1st ed. ed. Middletown: Conn., Wesleyan University Press, 1971. Badly water damaged, replace. -

A Reader's Companion

A Reader’s Companion to the Novel ALEMETH with Commentary by the Author in Which Particular Attention is Given to What is Real and What is Not jwcarvin © 2017 WARNING This Reader’s Companion is meant to be read after the novel, Alemeth, is read. It contains plot spoilers and other information which may detract from appreciation of the novel. i ii Introduction I am intrigued by the past for the reason William Faulkner gave: that it is not, really, even past. It not only shaped us to be who we are; it is, in a real sense, who we are, and we can never escape its grasp. I am also intrigued by the challenge of reconstructing it. Understanding what is real about it, and what is not, is almost the same thing as understanding ourselves, and nearly as hard. As Gordon Falkner points out in Chapter 67, we’re on a steamboat of present time: after we’ve gone a few feet upriver, the murky bottom will never be as it was when we first passed through it. Even as I write, pieces of evidence are settling behind me, and not (I hasten to point out) as they first lay. What should I expect to find when I turn back to examine them, stirring things up again as I do? Can I keep my own perspective, all my assumptions and biases, from affecting what I see? Reconstructing the past necessarily involves an effort to separate fact from fiction. But as Don Doyle writes in his wonderful book, Faulkner’s County,1 “historians are among the first to admit that the distinction between fact and fiction is hardly clear cut.” The best historians sometimes get things wrong. -

Flagship Achievements

THE ANNUAL REPORT ON PHILANTHROPY FOR THE YEAR ENDED JUNE 30, 2016 Changing Lives and FLAGSHIP Communities Through ACHIEVEMENTS Knowledge and Unity THE UNIVERSITY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI OLE MISS ATHLETICS MISSISSIPPI FOUNDATION MEDICAL CENTER FOUNDATION TOTAL ENDOWMENT PRIVATE SUPPORT BENEFITING THE FOR THE FISCAL YEAR UNIVERSITY OF MISSISSIPPI ENDED JUNE 30, 2016 36% $603 MILLION $61.45 21.2% $118.8 MILLION ACADEMIC AND PROGRAM SUPPORT NEW PLEDGES % MILLION FACULTY SUPPORT 38.8 RECEIVABLE IN FUTURE YEARS LIBRARY SUPPORT % SCHOLARSHIP SUPPORT 4 CASH AND $14.12 DEFERRED AND REALIZED GIFTS MILLION PLANNED GIFTS $194.3 RECENT PRIVATE SUPPORT $133.2 IN MILLIONS $122.6 $114.6 $118 $80.3 $78 $68.2 $65.2 $69.1 $67.8 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS MESSAGE FROM THE CHANCELLOR ............................................................... 4 UMMC Academic Leadership ................................................................... 42 Introduction: UMMC Development and Alumni Staff ..................................................... 43 FLAGSHIP ACHIEVEMENTS ..................................................................... 6 Major Donors ........................................................................................... 10 MESSAGE FROM OLE MISS ATHLETICS FOUNDATION CHAIR .......................... 44 MESSAGE FROM UM FOUNDATION BOARD CHAIR ......................................... 20 Ole Miss Athletics: TEAM VICTORIES, FACILITIES MIRROR HISTORIC SUPPORT ............... 46 UM Foundation: -

Alice Walker Papers, Circa 1930-2014

WALKER, ALICE, 1944- Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Emory University Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library Atlanta, GA 30322 404-727-6887 [email protected] Digital Material Available in this Collection Descriptive Summary Creator: Walker, Alice, 1944- Title: Alice Walker papers, circa 1930-2014 Call Number: Manuscript Collection No. 1061 Extent: 138 linear feet (253 boxes), 9 oversized papers boxes and 1 oversized papers folder (OP), 10 bound volumes (BV), 5 oversized bound volumes (OBV), 2 extraoversized papers folders (XOP) 2 framed items (FR), AV Masters: 5.5 linear feet (6 boxes and CLP), and 7.2 GB of born digital materials (3,054 files) Abstract: Papers of Alice Walker, an African American poet, novelist, and activist, including correspondence, manuscript and typescript writings, writings by other authors, subject files, printed material, publishing files and appearance files, audiovisual materials, photographs, scrapbooks, personal files journals, and born digital materials. Language: Materials mostly in English. Administrative Information Restrictions on Access Special restrictions apply: Selected correspondence in Series 1; business files (Subseries 4.2); journals (Series 10); legal files (Subseries 12.2), property files (Subseries 12.3), and financial records (Subseries 12.4) are closed during Alice Walker's lifetime or October 1, 2027, whichever is later. Series 13: Access to processed born digital materials is only available in the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library (the Rose Library). Use of the original digital media is restricted. The same restrictions listed above apply to born digital materials. Emory Libraries provides copies of its finding aids for use only in research and private study.