Writing Against the Odds: the South's Cultural and Literary Struggle

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 of 2020 to Understate It—2020 Was Not Square Books’ Best Year

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 OF 2020 To understate it—2020 was not Square Books’ best year. Like everyone, we struggled—but we are grateful to remain in business, and that all the booksellers here are healthy. When Covid19 arrived, our foot-traffic fell precipitously, and sales with it—2020 second-quarter sales were down 52% from those of the same period in 2019. But our many loyal customers adjusted along with us as we reopened operations when we were more confident of doing business safely. The sales trend improved in the third quarter, and November/December were only slightly down compared to those two months last year. We are immensely grateful to those of you who ordered online or by phone, allowing us to ship, deliver, or hold for curbside pickup, or who waited outside our doors to enter once our visitor count was at capacity. It is only through your abiding support that Square Books remains in business, ending the year down 30% and solid footing to face the continuing challenge of Covid in 2021. And there were some very good books published, of which one hundred bestsellers we’ll mention now. (By the way, we still have signed copies of many of these books; enquire accordingly.) Many books appear on this list every year—old favorites, if you will, including three William Faulkner books: Selected Short Stories (37th on our list) which we often recommend to WF novices, The Sound and the Fury (59) and As I Lay Dying (56), as well as a notably good new biography of Faulkner by Michael Gorra, The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War (61). -

Is Hip Hop Dead?

IS HIP HOP DEAD? IS HIP HOP DEAD? THE PAST,PRESENT, AND FUTURE OF AMERICA’S MOST WANTED MUSIC Mickey Hess Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Hess, Mickey, 1975- Is hip hop dead? : the past, present, and future of America’s most wanted music / Mickey Hess. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 (alk. paper) 1. Rap (Music)—History and criticism. I. Title. ML3531H47 2007 782.421649—dc22 2007020658 British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data is available. Copyright C 2007 by Mickey Hess All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, by any process or technique, without the express written consent of the publisher. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 2007020658 ISBN-13: 978-0-275-99461-7 ISBN-10: 0-275-99461-9 First published in 2007 Praeger Publishers, 88 Post Road West, Westport, CT 06881 An imprint of Greenwood Publishing Group, Inc. www.praeger.com Printed in the United States of America The paper used in this book complies with the Permanent Paper Standard issued by the National Information Standards Organization (Z39.48–1984). 10987654321 CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS vii INTRODUCTION 1 1THE RAP CAREER 13 2THE RAP LIFE 43 3THE RAP PERSONA 69 4SAMPLING AND STEALING 89 5WHITE RAPPERS 109 6HIP HOP,WHITENESS, AND PARODY 135 CONCLUSION 159 NOTES 167 BIBLIOGRAPHY 179 INDEX 187 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The support of a Rider University Summer Fellowship helped me com- plete this book. I want to thank my colleagues in the Rider University English Department for their support of my work. -

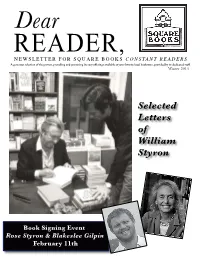

Selected Letters of William Styron

Dear Winter 2013 Selected Letters of William Styron Book Signing Event Rose Styron & Blakeslee Gilpin February 11th THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2012 With 2012 in rear view, we are very thankful for the many writers who came to us and the publishers who sent them to Square Books, as their books tend to dominate our bestseller list; some, like James Meek (The Heart Broke In, #30) and Lawrence Norfolk (John Saturnall’s Feast, #29), from as far as England – perhaps it’s the fascination with Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey (67) or J. K. Rowling’s Casual Vacancy (78). But as Dear Readers know, this list is usually crowded with those who live or have lived here, like Dean Wells’ Every Day by the Sun (22) or (long ago) James Meredith (A Mission From God, (10); William Faulkner’s Selected Stories (43), Ole Miss at Oxford, by Bill Morris (37), Mike Stewart’s Sporting Dogs and Retriever Training (39), John Brandon’s A Million Heavens (24), Airships (94), by Barry Hannah, Dream Cabinet by Ann Fisher-Wirth (87), Beginnings & Endings (85) by Ron Borne, Facing the Music (65) by Larry Brown, Neil White’s In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (35), the King twins’ Y’all Twins? (12), Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter Crooked Letter (13), The Fall of the House of Zeus (15) by Curtis Wilkie, Julie Cantrell’s Into the Free (16), Ole Miss Daily Devotions (18), and two perennial local favorites Wyatt Waters’ Oxford Sketchbook (36) and Square Table (8), which has been in our top ten ever since it was published; not to forget Sam Haskell and Promises I Made My Mother (6) or John Grisham, secure in the top two spots with The Racketeer and Calico Joe, nor our friend Richard Ford, with his great novel, Canada (5). -

Faulkner's Wake: the Emergence of Literary Oxford

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2004 Faulkner's Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford John Louis Fuller Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Fuller, John Louis, "Faulkner's Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford" (2004). Honors Theses. 2005. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2005 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faulkner’s Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford Bv John L. Fuller A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford April 2005 Advisor; Dr. Judson D. Wafson -7 ■ / ^—- Reader: Dr. Benjamin F. Fisher y. Reader: Dr. Andrew P. D^rffms Copyright © by John L. Fuller All Rights Reserved 1 For my parents Contents Abstract 5 I The Beginnings 9 (4Tell About the South 18 A Literary Awakening 25 II If You Build It, They Will Come 35 An Interview with Pochard Howorth 44Football, Faulkner, and Friends 57 An Interview with Barry Hannah Advancing Oxford’s Message 75 An Interview with Ann J. Abadie Oxford Tom 99 An Interview with Tom Franklin III Literary Grounds 117 Works cited 120 Abstract The genesis of this project was a commercial I saw on television advertising the University of Mississippi. “Is it the words that capture a place, or the place that captures the words?” noted actor and Mississippi native Morgan Freeman asked. -

Fall2011.Pdf

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Granta Fall 201 1 NOW AVAILABLE Complete and updated coverage by The New York Times about WikiLeaks and their controversial release of diplomatic cables and war logs OPEN SECRETS WikiLeaks, War, and American Diplomacy The New York Times Introduction by Bill Keller • Essential, unparalleled coverage A New York Times Best Seller from the expert writers at The New York Times on the hundreds he controversial antisecrecy organization WikiLeaks, led by Julian of thousands of confidential Assange, made headlines around the world when it released hundreds of documents revealed by WikiLeaks thousands of classified U.S. government documents in 2010. Allowed • Open Secrets also contains a T fascinating selection of original advance access, The New York Times sorted, searched, and analyzed these secret cables and war logs archives, placed them in context, and played a crucial role in breaking the WikiLeaks story. • online promotion at Open Secrets, originally published as an e-book, is the essential collection www.nytimes.com/opensecrets of the Times’s expert reporting and analysis, as well as the definitive chronicle of the documents’ release and the controversy that ensued. An introduction by Times executive editor, Bill Keller, details the paper’s cloak-and-dagger “We may look back at the war logs as relationship with a difficult source. Extended profiles of Assange and Bradley a herald of the end of America’s Manning, the Army private suspected of being his source, offer keen insight engagement in Afghanistan, just as into the main players. Collected news stories offer a broad and deep view into the Pentagon Papers are now a Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the messy challenges facing American power milestone in our slo-mo exit from in Europe, Russia, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. -

Finding Camus's Absurd in Faulkner's As I Lay Dying, the Sound and The

Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Graduate Theses and Dissertations Dissertations 2009 Finding Camus's absurd in Faulkner's As I Lay Dying, The oundS and the Fury, and Absalom, Absalom! Stuart Weston Iowa State University Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons, and the Rhetoric and Composition Commons Recommended Citation Weston, Stuart, "Finding Camus's absurd in Faulkner's As I Lay Dying, The oundS and the Fury, and Absalom, Absalom!" (2009). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 10628. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/etd/10628 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Iowa State University Capstones, Theses and Dissertations at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Finding Camus’s absurd in Faulkner’s As I Lay Dying, The Sound and the Fury, and Absalom, Absalom! by Stuart Michael Weston A thesis submitted to the graduate faculty in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS Major: English (Literature) Program of Study Committee: Diane Price-Herndl, Major Professor Susan Yager Jean Goodwin Iowa State University Ames, Iowa 2009 ii Table of Contents Chapter One: A New Context for the Absurd…………………………………………. 1 Chapter Two: 'Something to Laugh at’: As I Lay Dying’s Absurdist Family Quest…. 10 Chapter Three: Absurd Americans: The Compsons’ Nihilistic Descent……………... 29 Chapter Four: Making Sense out of Absurdity………………………………………..55 Bibliography …………………………………………………………………………… 61 1 Chapter One: A New Context for the Absurd When literary critics speak of the absurd, they frequently do so in the context of those writers who developed and popularized the concept; the origins of the concept are European and are often traced back to Soren Kierkegaard’s The Sickness unto Death , published in 1849. -

An Annotated Bibliography of William Faulkner, 1967-1970

Studies in English Volume 12 Article 3 1971 An Annotated Bibliography of William Faulkner, 1967-1970 James Barlow Lloyd University of Mississippi Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng Part of the American Literature Commons Recommended Citation Lloyd, James Barlow (1971) "An Annotated Bibliography of William Faulkner, 1967-1970," Studies in English: Vol. 12 , Article 3. Available at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/ms_studies_eng/vol12/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the English at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Studies in English by an authorized editor of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Lloyd: Faulkner Bibliography An Annotated Bibliography of William Faulkner, 1967—1970 by James Barlow Lloyd This annotated bibliography of books and articles published about William Faulkner and his works between January, 1967, and the summer of 1970 supplements such existing secondary bibliog raphies as Maurice Beebe’s checklists in the Autumn 1956 and Spring 1967 issues of Modern Fiction Studies; Linton R. Massey’s William Faulkner: “Man Working” 1919-1962: A Catalogue of the William Faulkner Collection of the University of Virginia (Charlottesville: Bibliographic Society of the University of Virginia, 1968); and O. B. Emerson’s unpublished doctoral dissertation, “William Faulkner’s Literary Reputation in America” (Vanderbilt University, 1962). The present bibliography begins where Beebe’s latest checklist leaves off, but no precise termination date can be established since publica tion dates for periodicals vary widely, and it has seemed more useful to cover all possible material than to set an arbitrary cutoff date. -

Art and Omnipotence: Genre Manipulation in Requiem for a Nun

ART AND OMNIPOTENCE: GENRE MANIPULATION IN REQUIEM FOR A NUN Requiem lor a Nun is usually classified as a novel. Yet it remains an irritating example of the genre, since it appears to defy even the loosest definition of a novel. Published in 1953, it consists of the three acts of a play called Requiem for a Nun, each of which is preceded by a long introduction see mingly unrelated to the action, if not the setting, of the play. Together, the introductions are about two-thirds as long as the play. If we consider that the text of a play, since it is not printed in continuous paragraphs, tends to take up more pages than narrative prose, we might actually end up with two Faulknerian texts of about equal length. Although Requiem lor a Nun has been produced as a play (most notably in 1956 at the Theatre des Mathurins under the direction of Albert Ca mus, who had also translated the text) the play cannot be truly understood if seen out of the context of the introductions. The story is a sequel to the events related in Sanctuary, published twenty years earlier in 1931, so that ideally even the play Re quiem lor a Nun requires a knowledge of the rest of the Faulk ner canon. Yet Temple Stevens, nee Drake, of Requiem for a Nun is no longer the Temple Drake of Sanctuary, nor is the Negress Nancy Mannigoe the Nancy of "That Evening Sun" (also published in 1931). Faulkner, although interested in the development of his characters, severs the ties between their 385 earlier and later versions because by the Fifties he had secretly become more interested in his own role as author. -

William Faulkner and the Meaning of History

Longwood University Digital Commons @ Longwood University Theses, Dissertations & Honors Papers 8-15-1978 William Faulkner and the Meaning of History Allen C. Lovelace Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.longwood.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons WILLIAM FAULKNER AND THE MEANING OF HISTORY by Allen c. Lovelace Firs Reader ��-c:.7eond Reader � (Repr�sentative of Graduate cil) THESIS Allen c. Lovelace, B. A. Graduate School Longwood College 1978 WILLIAM FAULKNER AND THE MEANING OF HISTORY Thesis A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment or the requirements for the degree or Master of Arts in English at Longwood College. by Allen c. Lovelace South Boston, Virginia Quentin Vest, Associate Professor of English Farmville, Virginia 1978 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A thesis, by its very nature, is the product not only of the writer, but also of the efforts of a number of other individuals. This paper is no exception, and I wish to ex press my indebtedness and sincerest appreciation to a nUJ.�ber of individuals. I am particularly grateful to Dr. Quentin Vest. Without his encouragement and guidance this paper would quite probably never have been written. I also wish to thank Dr. Vest for his patience with my tendency toward pro crastination. 1 '1hanks are due also to my wife, Carole, for her un derstanding and encouragement during the writing of this paper, and especially for the typing of the manuscript. I also wish to express my appreciation for their time and consideration to those members of the faculty at Longwood College who were my readers and to the Dabney Lancaster Library for their services which I found especial ly helpful. -

Oxford Conference for the Book Participants, 2003–2012

Oxford Conference for the Book Participants, 2003–2012 JEFFREY RENARD ALLEN is the author of two collections of poetry, Stellar Places and Harbors and Saints, and a novel, Rails Under My Back, which won the Chicago Tribune’s Heartland Prize for Fiction. He has also published essays, poems, and short stories in numerous publications and is currently completing his second novel, Song of the Shank, based on the life of Thomas Greene Wiggins, a 19th-century African American piano virtuoso and composer who performed under the stage name Blind Tom. Allen is an associate professor of English at Queens College of the City University of New York and an instructor in the MFA writing program at New School University. (2008) STEVE ALMOND is the author of the story collections My Life in Heavy Metal and The Evil B. B. Chow and Other Stories, as well as the nonfiction work Candyfreak. Almond has published stories and poems in such publications as Playboy, Tin House, and Zoetrope: All-Story; and many have been anthologized. He is a regular commentator on the NPR affiliate WBUR in Boston and teaches creative writing at Boston College. (2005) STEVEN AMSTERDAM is the author of Things We Didn’t See Coming, a debut collection of stories published to rave reviews in February 2009. Amsterdam, a native New Yorker, moved to Melbourne, Australia, in 2003, where he is employed as a psychiatric nurse and is writing his second book. (2010) BILL ANDERSON is the second child and older son of Walter Anderson and his wife, Agnes Grinstead Anderson. -

Finding Aid for the the Oxford American Collection (MUM00347)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the The Oxford American Collection (MUM00347) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation The Oxford American Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Finding Aid for the The Oxford American Collection (MUM00347) Questions? Contact us! The Oxford American Collection is open for research. Material separated for preservation, such as photographs, cassette tapes and computer discs, are stored at an off-site facility. Researchers interested in using this collection must contact Archives and Special Collections at least two business days in advance of their planned visit Finding Aid for the The Oxford American Collection Table of Contents Descriptive Summary Administrative Information Subject Terms Historical Note Scope and Content Note User Information Related Material Separated Material Arrangement Container List Descriptive Summary Title: The Oxford American Collection Dates: 1988-2002 Collector: Smirnoff, Marc ; Oxford American Physical Extent: 85 boxes (46 linear feet) + Unprocessed Materials Repository: University of Mississippi. Department of Archives and Special Collections. University, MS 38677, USA Identification: MUM00347 Location: J.D. Williams Library & Library Annex Language of Material: English Abstract: Manuscripts & production materials related to The Oxford American magazine, a prominent literary journal. Administrative Information Acquisition Information Materials donated by the Marc Smirnoff, founder and editor of the The Oxford American. -

Finding Aid for the Faulkner Periodicals Collection (MUM00161)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Faulkner Periodicals Collection (MUM00161) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Faulkner Periodicals Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Finding Aid for the Faulkner Periodicals Collection (MUM00161) Questions? Contact us! The Faulkner Periodicals Collection is open for research. Finding Aid for the Faulkner Periodicals Collection Table of Contents Descriptive Summary Administrative Information Subject Terms Collection History Scope and Content Note User Information Related Material Arrangement Container List Descriptive Summary Title: Faulkner Periodicals Collection Dates: 1930-1997 Collector: Wynn, Douglas C. ; Wynn, Leila Clark ; University of Mississippi. Dept. of Archives and Special Collections Physical Extent: 27 full Hollinger boxes ; 6 half boxes ; 1 oversize box ; 22 cartons (35.85 linear feet) Repository: University of Mississippi. Department of Archives and Special Collections. University, MS 38677, USA Identification: MUM00161 Language of Material: English Abstract: Collection of magazine and newspaper articles written by or concerning William Faulkner and University of Mississippi Yearbooks referencing Faulkner. Administrative Information Processing Information Collections processed by Archives and Special Collections staff. Series III-IV, Periodicals by Faulkner and Periodicals about Faulkner, originally processed by Jill Applebee and Amanda Strickland, August-September 1999. Multiple collections combined into single finding aid and encoded by Jason Kovari, August 2009.