Oral Tradition 22.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Still on the Road 2000 Us Summer Tour

STILL ON THE ROAD 2000 US SUMMER TOUR JUNE 15 Portland, Oregon Roseland Theater 16 Portland, Oregon Portland Meadows 17 George, Washington The Gorge 18 George, Washington The Gorge 20 Medford, Oregon Jackson County Expo Hall 21 Marysville, California Sacramento Valley Amphitheater 23 Concord, California Chronicle Pavilion 24 Mountain View, California Shoreline Amphitheatre 25 Reno, Nevada Reno Hilton Amphitheatre 27 Las Vegas, Nevada House Of Blues, Mandalay Bay Resort & Casino 29 Irvine, California Verizon Wireless Amphitheater 30 Ventura, California Arena, Ventura County Fairgrounds JULY 1 Del Mar, California Grandstand, Del Mar Fairgrounds 3 Albuquerque, New Mexico Mesa Del Sol Amphitheater 6 Oklahoma City, Oklahoma The Zoo Amphitheater 7 Bonner Springs, Kansas Sandstone Amphitheatre 8 Maryland Heights, Missouri Riverport Amphitheater 9 Noblesville, Indiana Deer Creek Music Center 11 Cincinnati, Ohio Riverbend Music Center 12 Moline, Illinois The Mark of the Quad Cities 14 Minneapolis, Minnesota Target Center 15 East Troy, Wisconsin Alpine Valley Music Theater 16 Clarkston, Michigan Pine Knob Music Theater 18 Toronto, Ontario, Canada Molson Amphitheatre 19 Canandaigua, New York Finger Lakes Performing Arts Center 21 Hartford, Connecticut Meadows Music Theatre 22 Mansfield, Massachusetts Tweeter Center for the Performing Arts 23 Saratoga Springs, Saratoga Performing Arts Center 25 Scranton, Pennsylvania Coors Light Amphitheatre 26 Wantagh, New York Jones Beach Amphitheatre 28 Camden, New Jersey E-Centre, Blockbuster-Sony Music Entertainment Centre 29 Columbia, Maryland Marjorie Merriweather Post Pavilion 30 Stanhope, New Jersey Waterloo Village Bob Dylan: Still On The Road – The 2000 US Summer Tour 21820 Roseland Theater Portland, Oregon 15 June 2000 1. Duncan And Brady (trad.) 2. -

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 of 2020 to Understate It—2020 Was Not Square Books’ Best Year

Dear READER, Winter/Spring 2021 SQUARE BOOKS TOP 100 OF 2020 To understate it—2020 was not Square Books’ best year. Like everyone, we struggled—but we are grateful to remain in business, and that all the booksellers here are healthy. When Covid19 arrived, our foot-traffic fell precipitously, and sales with it—2020 second-quarter sales were down 52% from those of the same period in 2019. But our many loyal customers adjusted along with us as we reopened operations when we were more confident of doing business safely. The sales trend improved in the third quarter, and November/December were only slightly down compared to those two months last year. We are immensely grateful to those of you who ordered online or by phone, allowing us to ship, deliver, or hold for curbside pickup, or who waited outside our doors to enter once our visitor count was at capacity. It is only through your abiding support that Square Books remains in business, ending the year down 30% and solid footing to face the continuing challenge of Covid in 2021. And there were some very good books published, of which one hundred bestsellers we’ll mention now. (By the way, we still have signed copies of many of these books; enquire accordingly.) Many books appear on this list every year—old favorites, if you will, including three William Faulkner books: Selected Short Stories (37th on our list) which we often recommend to WF novices, The Sound and the Fury (59) and As I Lay Dying (56), as well as a notably good new biography of Faulkner by Michael Gorra, The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War (61). -

Bob Dylan Bob Dylan's 50Th Anniversary Collection: 1965 Mp3, Flac, Wma

Bob Dylan Bob Dylan's 50th Anniversary Collection: 1965 mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Rock / Blues / Folk, World, & Country Album: Bob Dylan's 50th Anniversary Collection: 1965 Country: US Released: 2015 Style: Folk Rock, Blues Rock, Rhythm & Blues MP3 version RAR size: 1115 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1121 mb WMA version RAR size: 1812 mb Rating: 4.2 Votes: 997 Other Formats: WAV VOC MP1 TTA MIDI VQF ASF Tracklist February 17, 1965 (Les Crane Show, WABC-TV Studios, New York City, New York) 1 It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue 4:24 2 It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) 7:25 March 27, 1965 (Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, Santa Monica, California) 3 To Ramona 4:22 4 Gates of Eden 7:13 5 If You Gotta Go, Go Now 2:11 6 It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) 7:34 7 Love Minus Zero/No Limit 4:04 8 Mr. Tambourine Man 5:27 9 Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right 3:27 10 With God On Our Side [incomplete] 1:22 11 She Belongs To Me 3:36 12 It Ain’t Me, Babe [incomplete] 1:10 13 The Lonesome Death of Hattie Carroll [incomplete] 0:20 14 All I Really Want To Do 2:22 15 It’s All Over Now, Baby Blue 4:41 April 30, 1965 (The Oval, City Hall, Sheffield, England) 16 The Times They Are A-Changin' 3:25 17 To Ramona 4:24 18 Gates of Eden 6:58 19 If You Gotta Go, Go Now 2:54 20 It's Alright, Ma (I'm Only Bleeding) 8:02 21 Love Minus Zero/No Limit 4:36 22 Mr. -

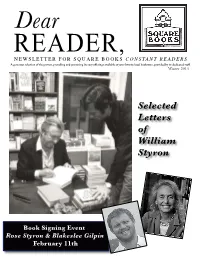

Selected Letters of William Styron

Dear Winter 2013 Selected Letters of William Styron Book Signing Event Rose Styron & Blakeslee Gilpin February 11th THE YEAR IN REVIEW 2012 With 2012 in rear view, we are very thankful for the many writers who came to us and the publishers who sent them to Square Books, as their books tend to dominate our bestseller list; some, like James Meek (The Heart Broke In, #30) and Lawrence Norfolk (John Saturnall’s Feast, #29), from as far as England – perhaps it’s the fascination with Lady Almina and the Real Downton Abbey (67) or J. K. Rowling’s Casual Vacancy (78). But as Dear Readers know, this list is usually crowded with those who live or have lived here, like Dean Wells’ Every Day by the Sun (22) or (long ago) James Meredith (A Mission From God, (10); William Faulkner’s Selected Stories (43), Ole Miss at Oxford, by Bill Morris (37), Mike Stewart’s Sporting Dogs and Retriever Training (39), John Brandon’s A Million Heavens (24), Airships (94), by Barry Hannah, Dream Cabinet by Ann Fisher-Wirth (87), Beginnings & Endings (85) by Ron Borne, Facing the Music (65) by Larry Brown, Neil White’s In the Sanctuary of Outcasts (35), the King twins’ Y’all Twins? (12), Tom Franklin’s Crooked Letter Crooked Letter (13), The Fall of the House of Zeus (15) by Curtis Wilkie, Julie Cantrell’s Into the Free (16), Ole Miss Daily Devotions (18), and two perennial local favorites Wyatt Waters’ Oxford Sketchbook (36) and Square Table (8), which has been in our top ten ever since it was published; not to forget Sam Haskell and Promises I Made My Mother (6) or John Grisham, secure in the top two spots with The Racketeer and Calico Joe, nor our friend Richard Ford, with his great novel, Canada (5). -

Durham E-Theses

Durham E-Theses `This is what Salvation must be like after a While': Bob Dylan's Critical Utopia KOUVAROU, MARIA How to cite: KOUVAROU, MARIA (2011) `This is what Salvation must be like after a While': Bob Dylan's Critical Utopia, Durham theses, Durham University. Available at Durham E-Theses Online: http://etheses.dur.ac.uk/1391/ Use policy The full-text may be used and/or reproduced, and given to third parties in any format or medium, without prior permission or charge, for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-prot purposes provided that: • a full bibliographic reference is made to the original source • a link is made to the metadata record in Durham E-Theses • the full-text is not changed in any way The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holders. Please consult the full Durham E-Theses policy for further details. Academic Support Oce, Durham University, University Oce, Old Elvet, Durham DH1 3HP e-mail: [email protected] Tel: +44 0191 334 6107 http://etheses.dur.ac.uk 2 ‘This is what Salvation must be like after a While’: Bob Dylan’s Critical Utopia Maria Kouvarou MA by Research in Musicology Music Department Durham University 2011 Maria Kouvarou ‘This is what Salvation must be like after a While’: Bob Dylan’s Critical Utopia Abstract Bob Dylan’s work has frequently been the object of discussion, debate and scholarly research. It has been commented on in terms of interpretation of the lyrics of his songs, of their musical treatment, and of the distinctiveness of Dylan’s performance style, while Dylan himself has been treated both as an important figure in the world of popular music, and also as an artist, as a significant poet. -

Bob Denson Master Song List 2020

Bob Denson Master Song List Alphabetical by Artist/Band Name A Amos Lee - Arms of a Woman - Keep it Loose, Keep it Tight - Night Train - Sweet Pea Amy Winehouse - Valerie Al Green - Let's Stay Together - Take Me To The River Alicia Keys - If I Ain't Got You - Girl on Fire - No One Allman Brothers Band, The - Ain’t Wastin’ Time No More - Melissa - Ramblin’ Man - Statesboro Blues Arlen & Harburg (Isai K….and Eva Cassidy and…) - Somewhere Over the Rainbow Avett Brothers - The Ballad of Love and Hate - Head Full of DoubtRoad Full of Promise - I and Love and You B Bachman Turner Overdrive - Taking Care Of Business Band, The - Acadian Driftwood - It Makes No Difference - King Harvest (Has Surely Come) - Night They Drove Old Dixie Down, The - Ophelia - Up On Cripple Creek - Weight, The Barenaked Ladies - Alcohol - If I Had A Million Dollars - I’ll Be That Girl - In The Car - Life in a Nutshell - Never is Enough - Old Apartment, The - Pinch Me Beatles, The - A Hard Day’s Night - Across The Universe - All My Loving - Birthday - Blackbird - Can’t Buy Me Love - Dear Prudence - Eight Days A Week - Eleanor Rigby - For No One - Get Back - Girl Got To Get You Into My Life - Help! - Her Majesty - Here, There, and Everywhere - I Saw Her Standing There - I Will - If I Fell - In My Life - Julia - Let it Be - Love Me Do - Mean Mr. Mustard - Norwegian Wood - Ob-La-Di Ob-La-Da - Polythene Pam - Rocky Raccoon - She Came In Through The Bathroom Window - She Loves You - Something - Things We Said Today - Twist and Shout - With A Little Help From My Friends - You’ve -

Ian Wooldridge Director

Ian Wooldridge Director For details of Ian's freelance productions, and his international work in training and education go to www.ianwooldridge.com Agents Nicki Stoddart [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0869 Credits Theatre Production Company Notes ARTISTIC DIRECTOR, ROYAL LYCEUM THEATRE COMPANY, EDINBURGH, 1984-1993 THE TAMING OF THE SHREW Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company, Edinburgh MERLIN Royal Lyceum Theatre Tankred Dorst Company Edinburgh ROMEO AND JULIET Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh THE CRUCIBLE Royal Lyceum Theatre Arthur Miller Company Edinburgh THE ODD COUPLE Royal Lyceum Theatre Neil Simon Company Edinburgh JUNO AND THE PAYCOCK Royal Lyceum Theatre Sean O'Casey Company Edinburgh OTHELLO Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Company Notes THE HOUSE OF BERNARDA ALBA Royal Lyceum Theatre Federico Garcia Lorca Company Edinburgh HOBSON'S CHOICE Royal Lyceum Theatre Harold Brighouse Company Edinburgh DEATH OF A SALESMAN Royal Lyceum Theatre Arthur Miller Company Edinburgh THE GLASS MENAGERIE Royal Lyceum Theatre Tennessee Williams Company, Edinburgh ALICE IN WONDERLAND Royal Lyceum Theatre Adapted from the novel by Lewis Company, Edinburgh Carroll A MIDSUMMER NIGHT'S DREAM Royal Lyceum Theatre Shakespeare Company Edinburgh A STREETCAR NAMED DESIRE Royal Lyceum Theatre Tennessee Williams Company, Edinburgh THE NUTCRACKER SUITE Royal Lyceum -

Faulkner's Wake: the Emergence of Literary Oxford

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2004 Faulkner's Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford John Louis Fuller Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Recommended Citation Fuller, John Louis, "Faulkner's Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford" (2004). Honors Theses. 2005. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/2005 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Faulkner’s Wake: The Emergence of Literary Oxford Bv John L. Fuller A thesis submitted to the faculty of The University of Mississippi in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College. Oxford April 2005 Advisor; Dr. Judson D. Wafson -7 ■ / ^—- Reader: Dr. Benjamin F. Fisher y. Reader: Dr. Andrew P. D^rffms Copyright © by John L. Fuller All Rights Reserved 1 For my parents Contents Abstract 5 I The Beginnings 9 (4Tell About the South 18 A Literary Awakening 25 II If You Build It, They Will Come 35 An Interview with Pochard Howorth 44Football, Faulkner, and Friends 57 An Interview with Barry Hannah Advancing Oxford’s Message 75 An Interview with Ann J. Abadie Oxford Tom 99 An Interview with Tom Franklin III Literary Grounds 117 Works cited 120 Abstract The genesis of this project was a commercial I saw on television advertising the University of Mississippi. “Is it the words that capture a place, or the place that captures the words?” noted actor and Mississippi native Morgan Freeman asked. -

Fall2011.Pdf

Grove Press Atlantic Monthly Press Black Cat The Mysterious Press Granta Fall 201 1 NOW AVAILABLE Complete and updated coverage by The New York Times about WikiLeaks and their controversial release of diplomatic cables and war logs OPEN SECRETS WikiLeaks, War, and American Diplomacy The New York Times Introduction by Bill Keller • Essential, unparalleled coverage A New York Times Best Seller from the expert writers at The New York Times on the hundreds he controversial antisecrecy organization WikiLeaks, led by Julian of thousands of confidential Assange, made headlines around the world when it released hundreds of documents revealed by WikiLeaks thousands of classified U.S. government documents in 2010. Allowed • Open Secrets also contains a T fascinating selection of original advance access, The New York Times sorted, searched, and analyzed these secret cables and war logs archives, placed them in context, and played a crucial role in breaking the WikiLeaks story. • online promotion at Open Secrets, originally published as an e-book, is the essential collection www.nytimes.com/opensecrets of the Times’s expert reporting and analysis, as well as the definitive chronicle of the documents’ release and the controversy that ensued. An introduction by Times executive editor, Bill Keller, details the paper’s cloak-and-dagger “We may look back at the war logs as relationship with a difficult source. Extended profiles of Assange and Bradley a herald of the end of America’s Manning, the Army private suspected of being his source, offer keen insight engagement in Afghanistan, just as into the main players. Collected news stories offer a broad and deep view into the Pentagon Papers are now a Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, and the messy challenges facing American power milestone in our slo-mo exit from in Europe, Russia, Asia, the Middle East, and Africa. -

The Songs of Bob Dylan

The Songwriting of Bob Dylan Contents Dylan Albums of the Sixties (1960s)............................................................................................ 9 The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan (1963) ...................................................................................................... 9 1. Blowin' In The Wind ...................................................................................................................... 9 2. Girl From The North Country ....................................................................................................... 10 3. Masters of War ............................................................................................................................ 10 4. Down The Highway ...................................................................................................................... 12 5. Bob Dylan's Blues ........................................................................................................................ 13 6. A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall .......................................................................................................... 13 7. Don't Think Twice, It's All Right ................................................................................................... 15 8. Bob Dylan's Dream ...................................................................................................................... 15 9. Oxford Town ............................................................................................................................... -

News Archive: May, 2003

News Archive: May, 2003 News Archive: May, 2003 News Briefs Briefs More News Web of Science Staff Pick Here's a searchable science database with loads of useful features. (4/30/03) Solari Nominations Sought May 19 is the deadline for nominating library faculty for the libraries' Solari Fellowships. (4/30/03) Ivory Reception Wednesday Famed filmmaker and UO alumnus James Ivory will be honored at a reception this Wednesday. (4/4/03) Serials Cancellations Imminent But faculty and GTFs still have a say in which titles stay and which go. Act before May 2. (4/23/03) James Ivory Exhibit Opens An exhibit of papers of famed filmmaker and UO alumnus James Ivory is now on display. (4/14/03) Your Comments, Please Help us evaluate Academic Search Premier, a major database of online journals. (4/10/03) New Databases Available Need to learn about medicinal chilies grown in Latin America? Or something a bit less specialized? Here’s help! (4/10/03) New Additions for March Discover the many new resources added to the libraries' collections in March. (4/7/03) Nobel Prize Resource Online The library offers a gateway to the lives and works of winners of the Nobel Prize for Literature. (4/4/03) Some Journal Issues Delayed Can't find a current issue of a journal? Here's help. (1/23/03) IT Courses Announced Upgrade your information technology (IT) skills with free workshops from the IT Curriculum. (03/20/03) More news ● What's New archive ● New Additions to UO Libraries http://libweb.uoregon.edu/news/whatsnew/archive/2003-05.htm (1 of 2)5/25/2006 10:00:08 AM News Archive: May, 2003 http://libweb.uoregon.edu/news/whatsnew/ Last revision: Thursday, May 1, 2003 (jqj) University of Oregon Libraries credits University of Oregon Libraries | Eugene, OR 97403-1299 http://libweb.uoregon.edu/news/whatsnew/archive/2003-05.htm (2 of 2)5/25/2006 10:00:08 AM Staff Picks: Web Of Science Staff Picks Featured Reference Work ISI's rather pompous-sounding Web of Science is actually the only database yet to exploit the capabilities of linking available with HTML, the web, and heck, computers in general. -

Still on the Road 1990 Us Fall Tour

STILL ON THE ROAD 1990 US FALL TOUR OCTOBER 11 Brookville, New York Tilles Center, C.W. Post College 12 Springfield, Massachusetts Paramount Performing Arts Center 13 West Point, New York Eisenhower Hall Theater 15 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 16 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 17 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 18 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 19 New York City, New York The Beacon Theatre 21 Richmond, Virginia Richmond Mosque 22 Pittsburg, Pennsylvania Syria Mosque 23 Charleston, West Virginia Municipal Auditorium 25 Oxford, Mississippi Ted Smith Coliseum, University of Mississippi 26 Tuscaloosa, Alabama Coleman Coliseum 27 Nashville, Tennessee Memorial Hall, Vanderbilt University 28 Athens, Georgia Coliseum, University of Georgia 30 Boone, North Carolina Appalachian State College, Varsity Gymnasium 31 Charlotte, North Carolina Ovens Auditorium NOVEMBER 2 Lexington, Kentucky Memorial Coliseum 3 Carbondale, Illinois SIU Arena 4 St. Louis, Missouri Fox Theater 6 DeKalb, Illinois Chick Evans Fieldhouse, University of Northern Illinois 8 Iowa City, Iowa Carver-Hawkeye Auditorium 9 Chicago, Illinois Fox Theater 10 Milwaukee, Wisconsin Riverside Theater 12 East Lansing, Michigan Wharton Center, University of Michigan 13 Dayton, Ohio University of Dayton Arena 14 Normal, Illinois Brayden Auditorium 16 Columbus, Ohio Palace Theater 17 Cleveland, Ohio Music Hall 18 Detroit, Michigan The Fox Theater Bob Dylan 1990: US Fall Tour 11530 Rose And Gilbert Tilles Performing Arts Center C.W. Post College, Long Island University Brookville, New York 11 October 1990 1. Marines' Hymn (Jacques Offenbach) 2. Masters Of War 3. Tomorrow Is A Long Time 4.