Intersectional Assimilation and the Ethnic Identities of Latinos/As

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

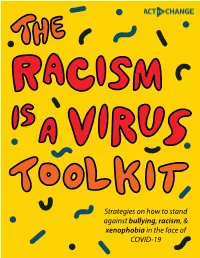

Racism Is a Virus Toolkit

Table of Contents About This Toolkit.............................................................................................................03 Know History, Know Racism: A Brief History of Anti-AANHPI Racism............04 Exclusion and Colonization of AANHPI People.............................................04 AANHPI Panethnicity.............................................................................................07 Racism Resurfaced: COVID-19 and the Rise of Xenophobia...............................08 Continued Trends....................................................................................................08 Testimonies...............................................................................................................09 What Should I Do If I’m a Victim of a Hate Crime?.........................................10 What Should I Do If I Witness a Hate Crime?..................................................12 Navigating Unsteady Waters: Confronting Racism with your Parents..............13 On Institutional and Internalized Anti-Blackness..........................................14 On Institutionalized Violence...............................................................................15 On Protests................................................................................................................15 General Advice for Explaning Anti-Blackness to Family.............................15 Further Resources...................................................................................................15 -

Download 2010 Census Race and Hispanic Origin Alternative

This document was prepared by and for Census Bureau staff to aid in future research and planning, but the Census Bureau is making the document publicly available in order to share the information with as wide an audience as possible. Questions about the document should be directed to Kevin Deardorff at (301) 763-6033 or [email protected] February 28, 2013 2010 CENSUS PLANNING MEMORANDA SERIES No. 211 (2nd Reissue) MEMORANDUM FOR The Distribution List From: Burton Reist [signed] Acting Chief, Decennial Management Division Subject: 2010 Census Race and Hispanic Origin Alternative Questionnaire Experiment Attached is the revised final report, “2010 Census Race and Hispanic Origin Alternative Questionnaire Experiment,” for the 2010 Census Program for Evaluations and Experiments (CPEX). This revision accounts for an update to Appendix A. If you have questions or comments about this report, please contact Joan Hill at (301) 763-4286 or Michael Bentley at (301) 763-4306. Attachment 2010 Census Program for Evaluations and Experiments 2010 Census Race and Hispanic Origin Alternative Questionnaire Experiment U.S. Census Bureau standards and quality process procedures were applied throughout the creation of this report. FINAL REPORT Elizabeth Compton Michael Bentley Sharon Ennis Sonya Rastogi Decennial Statistical Studies Division and Population Division This page intentionally left blank. i Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... vi -

The Invention of Asian Americans

The Invention of Asian Americans Robert S. Chang* Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 947 I. Race Is What Race Does ............................................................................................ 950 II. The Invention of the Asian Race ............................................................................ 952 III. The Invention of Asian Americans ....................................................................... 956 IV. Racial Triangulation, Affirmative Action, and the Political Project of Constructing Asian American Communities ............................................ 959 Conclusion ........................................................................................................................ 964 INTRODUCTION In Fisher v. University of Texas,1 the U.S. Supreme Court will revisit the legal status of affirmative action in higher education. Of the many amicus curiae (friend of the court) briefs filed, four might be described as “Asian American” briefs.2 * Copyright © 2013 Robert S. Chang, Professor of Law and Executive Director, Fred T. Korematsu Center for Law and Equality, Seattle University School of Law. I draw my title from THEODORE W. ALLEN, THE INVENTION OF THE WHITE RACE, VOL. 1: RACIAL OPPRESSION AND SOCIAL CONTROL (1994), and THEODORE W. ALLEN, THE INVENTION OF THE WHITE RACE, VOL. 2: THE ORIGIN OF RACIAL OPPRESSION IN ANGLO AMERICA (1997). I also note the similarity of my title to Neil Gotanda’s -

Uncovering Nodes in the Transnational Social Networks of Hispanic Workers

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Doctoral Dissertations Graduate School 2013 Uncovering nodes in the transnational social networks of Hispanic workers James Powell Chaney Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations Part of the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Chaney, James Powell, "Uncovering nodes in the transnational social networks of Hispanic workers" (2013). LSU Doctoral Dissertations. 3245. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/3245 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized graduate school editor of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please [email protected]. UNCOVERING NODES IN THE TRANSNATIONAL SOCIAL NETWORKS OF HISPANIC WORKERS A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of Geography & Anthropology by James Powell Chaney B.A., University of Tennessee, 2001 M.S., Western Kentucky University 2007 December 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS As I sat down to write the acknowledgment for this research, something ironic came to mind. I immediately realized that I too had to rely on my social network to complete this work. No one can achieve goals without the engagement and support of those to whom we are connected. As we strive to succeed in life, our family, friends and acquaintances influence us as well as lend a much needed hand. -

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: a Multilevel Process Theory1

The Making and Unmaking of Ethnic Boundaries: A Multilevel Process Theory1 Andreas Wimmer University of California, Los Angeles Primordialist and constructivist authors have debated the nature of ethnicity “as such” and therefore failed to explain why its charac- teristics vary so dramatically across cases, displaying different de- grees of social closure, political salience, cultural distinctiveness, and historical stability. The author introduces a multilevel process theory to understand how these characteristics are generated and trans- formed over time. The theory assumes that ethnic boundaries are the outcome of the classificatory struggles and negotiations between actors situated in a social field. Three characteristics of a field—the institutional order, distribution of power, and political networks— determine which actors will adopt which strategy of ethnic boundary making. The author then discusses the conditions under which these negotiations will lead to a shared understanding of the location and meaning of boundaries. The nature of this consensus explains the particular characteristics of an ethnic boundary. A final section iden- tifies endogenous and exogenous mechanisms of change. TOWARD A COMPARATIVE SOCIOLOGY OF ETHNIC BOUNDARIES Beyond Constructivism The comparative study of ethnicity rests firmly on the ground established by Fredrik Barth (1969b) in his well-known introduction to a collection 1 Various versions of this article were presented at UCLA’s Department of Sociology, the Institute for Migration Research and Intercultural Studies of the University of Osnabru¨ ck, Harvard’s Center for European Studies, the Center for Comparative Re- search of Yale University, the Association for the Study of Ethnicity at the London School of Economics, the Center for Ethnicity and Citizenship of the University of Bristol, the Department of Political Science and International Relations of University College Dublin, and the Department of Sociology of the University of Go¨ttingen. -

Predicting Ethnic Boundaries Sun-Ki Chai

European Sociological Review VOLUME 21 NUMBER 4 SEPTEMBER 2005 375–391 375 DOI:10.1093/esr/jci026, available online at www.esr.oxfordjournals.org Online publication 22 July 2005 Predicting Ethnic Boundaries Sun-Ki Chai It is increasingly accepted within the social sciences that ethnic boundaries are not fixed, but contingent and socially constructed. As a result, predicting the location of ethnic boundaries across time and space has become a crucial but unresolved issue, with some scholars arguing that the study of ethnic boundaries and predictive social science are fun- damentally incompatible. This paper attempts to show otherwise, presenting perhaps the first general, predictive theory of ethnic boundary formation, one that combines a coher- ence-based model of identity with a rational choice model of action. It then tests the the- ory’s predictions, focusing in particular on the size of populations generated by alternative boundary criteria. Analysis is performed using multiple datasets containing information about ethnic groups around the world, as well as the countries in which they reside. Perhaps the best-known innovation in contemporary encompassing all ascriptively-based group boundaries, theories of ethnicity is the idea that ethnic boundaries including those based upon race, religion, language, are not predetermined by biology or custom, but malle- and/or region. Characteristics such as religion, language, able and responsive to changes in the surrounding social and region are viewed as ascriptive rather than cultural environment. Ethnicity is seen to be socially con- because they are typically defined for purposes of ethnic- structed, and the nature of this construction is seen to ity to refer not to the current practice or location of indi- vary from situation to situation.1 This in turn has linked viduals, but rather to their lineage, the customs of their to a more general concern with the contruction of social ancestors. -

Disentangling Immigrant Generations

THEORIZING AMERICAN GIRL ________________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ________________________________________________________________ by VERONICA E. MEDINA Dr. David L. Brunsma, Thesis Advisor MAY 2007 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THEORIZING AMERICAN GIRL Presented by Veronica E. Medina A candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor David L. Brunsma Professor Mary Jo Neitz Professor Lisa Y. Flores DEDICATION My journey to and through the master’s program has never been a solitary one. My family has accompanied me every step of the way, encouraging and supporting me: materially and financially, emotionally and spiritually, and academically. From KU to MU, you all loved me and believed in me throughout every endeavor. This thesis is dedicated to my family, and most especially, to my parents Alicia and Francisco Medina. Mom and Dad: As a child, I often did not recognize and, far too often, took for granted the sacrifices that you made for me. Sitting and writing a thesis is a difficult task, but it is not as difficult as any of the tasks you two undertook to ensure my well-being, security, and happiness and to see me through to this goal. For all of the times you went without (and now, as an adult, I know that there were many) so that we would not, thank you. -

De-Conflating Latinos/As' Race and Ethnicity

UCLA Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review Title Los Confundidos: De-Conflating Latinos/As' Race and Ethnicity Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9nx2r4pj Journal Chicana/o Latina/o Law Review, 19(1) ISSN 1061-8899 Author Sandrino-Glasser, Gloria Publication Date 1998 DOI 10.5070/C7191021085 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California LOS CONFUNDIDOS: DE-CONFLATING LATINOS/AS' RACE AND ETHNICITY GLORIA SANDRmNO-GLASSERt INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................71 I. LATINOS: A DEMOGRAPHIC PORTRAIT ..............................................75 A. Latinos: Dispelling the Legacy of Homogenization ....................75 B. Los Confundidos: Who are We? (Qui6n Somos?) ...................77 1. Mexican-Americans: The Native Sons and D aughters .......................................................................77 2. Mainland Puerto Ricans: The Undecided ..............................81 3. Cuban-Americans: Last to Come, Most to Gain .....................85 II. THE CONFLATION: AN OVERVIEW ..................................................90 A. The Conflation in Context ........................................................95 1. The Conflation: Parts of the W hole ..........................................102 2. The Conflation Institutionalized: The Sums of All Parts ...........103 B. The Conflation: Concepts and Definitions ...................................104 1. N ationality ..............................................................................104 -

Building Panethnic Coalitions in Asian American, Native Hawaiian And

Building Panethnic Coalitions in Asian American, Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islander Communities: Opportunities & Challenges This paper is one in a series of evaluation products emerging states around the country were supported through this pro- from Social Policy Research Associates’ evaluation of Health gram, with the Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum Through Action (HTA), a $16.5 million, four-year W.K. Kellogg serving as the national advocacy partner and technical assis- Foundation supported initiative to reduce disparities and tance hub. advance healthy outcomes for Asian American, Native Hawai- Each of the HTA partners listed below have made mean- ian, and Pacific Islander (AA and NHPI) children and families. ingful inroads towards strengthening local community capacity A core HTA strategy is the Community Partnerships Grant to address disparities facing AA and NHPIs, as well as sparked Program, a multi-year national grant program designed to a broader national movement for AA and NHPI health. The strengthen and bolster community approaches to improv- voices of HTA partners – their many accomplishments, moving ing the health of vulnerable AA and NHPIs. Ultimately, seven stories, and rich lessons learned from their experience – serve AA and NHPI collaboratives and 11 anchor organizations in 15 as the basis of our evaluation. National Advocacy Partner HTA Organizational Partners Asian & Pacific Islander American Health Forum – West Michigan Asian American Association – Asian Pacific American Network of Oregon HTA Regional -

Stress Biomarkers and Latinos' Exposure to the United States

Stress biomarkers and Latinos’ exposure to the United States by Nicole Louise Novak A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Epidemiological Science) in the University of Michigan 2016 Doctoral Committee: Dean Ana V. Diez Roux, Drexel University, Co-Chair Professor Philippa J. Clarke, Co-Chair Professor Arline T. Geronimus Assistant Professor Belinda L. Needham Associate Professor Brisa N. Sánchez © Nicole L. Novak 2016 DEDICATION For my family: Tom Novak and Louise Wolf-Novak Daniel Novak, Sheila Hager Novak, Bridget Novak and Kurt Novak Hager Tom and Carol Novak Hugo and Agnes Wolf …and Ethan Forsgren ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am humbled as I look back on the many individuals and communities who have supported me in pursuing this degree. I am grateful for the time, patience, critical thought, and love that so many have shared with me—this dissertation and the ideas it contains are far from mine alone. I am especially grateful to my mentors and committee co-chairs, Ana Diez Roux and Philippa Clarke, who have supported and encouraged me from the very beginning. Looking back at my application essay to Michigan’s PhD program in Epidemiology, I listed research interests as diverse as agricultural health, Foucauldian biopolitics and epigenetics! I am grateful for their bravery in taking me on, and for their patience, trust and guidance as my interests eventually became focused research questions that continue to ignite me. I am endlessly impressed by Ana’s dedication as a mentor and her generosity with her time and expertise even from afar. -

•Œshe Called Me a Mexican!•Š: a Study of Ethnic Identity

University of Northern Iowa UNI ScholarWorks Electronic Theses and Dissertations Graduate College 2008 “She called me a Mexican!”: a study of ethnic identity Simona Florentina Boroianu University of Northern Iowa Copyright ©2007 Simona Florentina Boroianu Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.uni.edu/etd Part of the Bilingual, Multilingual, and Multicultural Education Commons, and the Elementary Education Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits oy u Recommended Citation 2018 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate College at UNI ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNI ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 'SHE CALLED ME A MEXICAN!"- A STUDY OF ETHNIC IDENTITY A Dissertation Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree Doctor of Education Approved: Dr. Robert Boody, Chair Dr. Flavia Vernescu, Co-Chair Dr. Radhi Al-Mabuk, Committee Member Dr. Kimberly Knesting, Committee Member Dr. Roger Kueter, Committee Member Simona Florentina Boroianu University of Northern Iowa December 2007 UMI Number: 3321004 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. -

Exploring Racial Label Preferences of African Americans and Afro- Caribbeans in the United States

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, MERCED Beyond Black: Exploring Racial Label Preferences of African Americans and Afro- Caribbeans in the United States A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Sociology by Breanna D. Brock Committee in charge: Whitney Pirtle, Chair Zulema Valdez Dawne Mouzon 2019 ©Breanna D. Brock, 2019 All rights reserved iii The Thesis of Breanna D. Brock is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm and electronically: Dr. Dawne Mouzon Dr. Zulema Valdez Dr. Whitney Pirtle, Chair University of California, Merced 2019 iii Table of Contents Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………………7 Introduction………………………………………………………………………………………..7 Literature Review..…………………………………..…………………………………………….8 Theorizing about Race, Ethnicity, and Identity of African Descendants Living in the United States …………………………………………….....……………………….…….8 Overview of Racial Labels in the United States…………....……………………………..9 Racial Labels as a Measure of Social Identity and Identification……..………………....12 Nativity and Discrimination as Correlates for Racial Label Preference among African Descendants……………………………………………………………….…………..…13 Methods…………………………………………………………………………………………..15 Data………………………………………………………………………………………15 Analysis Plan………………………………………………………………………....….18 Results……………………...………………………………………………………………….....18 Discussion………………..…………..…………………………………………………………..23 References………………………………………………………………………………………..34 iv List of Tables Table 1. Demographics by Nativity/Ancestry