Disentangling Immigrant Generations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eyeclops Bionic Eye From

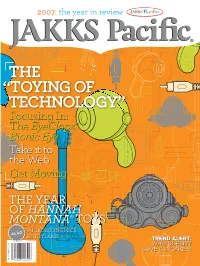

2007: the year in review THE “TOYING OF TECHNOLOGY” FocusingFocusing In:In: TheThe EyeClopsEyeClops®® BionicBionic EyeEye TakeTake itit toto thethe WebWeb GetGet MovingMoving THE YEAR OF HANNAH MONTANA® TOYS MICROECONOMICS ALSO IN TOYLAND TRENDTREND ALERT:ALERT: WHOWHO DOESN’TDOESN’T LOVELOVE CUPCAKES?CUPCAKES? AR 2007 $PRICELESS AR 2007 TABLE of CONTENTS JAKKS’ 4Girl POWER! In 2007 Disney® “It Girl” Miley Cyrus, a.k.a. Hannah Montana, hit the scene, and JAKKS was right there with her to catch the craze. Tween girls weren’t the only ones who took notice of the teen phenom. Hannah Montana toys from JAKKS were nominated for “Girls Toy of the Year” by the Toy Industry Association, received a 2008 LIMA licensing excellence award, and numerous retailers and media outlets also chose them as their top holiday picks for 2007. WIRED: SPOTLIGHT 6 on TECHNOLOGY From video game controllers to scientific magnifiers – in 2007 JAKKS expanded on its award-winning Plug It In & Play TV Games™ technology and created the EyeClops Bionic Eye, an innovative, handheld version of a traditional microscope for today’s savvy kids. JAKKS continued to amaze BOYS the action figure community will be by shipping more than 500 unique WWE® and BOYS Pokémon® figures to 8 retailers in more than 60 countries around the world in 2007. Joining the JAKKS powerhouse male action portfolio for 2008 and 2009 are The Chronicles of Narnia™: Prince Caspian™, American Gladiators®, NASCAR® and UFC Ultimate Fighting Championship® product lines, and in 2010… TNA® Total Non-Stop Action Wrestling™ toys. W e Hop e You E the Ne njoy w Ma gazine Format! - th 6 e editor 2007 ANNUAL REPORT THIS BOOK WAS PRINTED WITH THE EARTH IN MIND 2 JAKKS Pacifi c is committed to being a philanthropic and socially responsible corporate citizen. -

Download 2010 Census Race and Hispanic Origin Alternative

This document was prepared by and for Census Bureau staff to aid in future research and planning, but the Census Bureau is making the document publicly available in order to share the information with as wide an audience as possible. Questions about the document should be directed to Kevin Deardorff at (301) 763-6033 or [email protected] February 28, 2013 2010 CENSUS PLANNING MEMORANDA SERIES No. 211 (2nd Reissue) MEMORANDUM FOR The Distribution List From: Burton Reist [signed] Acting Chief, Decennial Management Division Subject: 2010 Census Race and Hispanic Origin Alternative Questionnaire Experiment Attached is the revised final report, “2010 Census Race and Hispanic Origin Alternative Questionnaire Experiment,” for the 2010 Census Program for Evaluations and Experiments (CPEX). This revision accounts for an update to Appendix A. If you have questions or comments about this report, please contact Joan Hill at (301) 763-4286 or Michael Bentley at (301) 763-4306. Attachment 2010 Census Program for Evaluations and Experiments 2010 Census Race and Hispanic Origin Alternative Questionnaire Experiment U.S. Census Bureau standards and quality process procedures were applied throughout the creation of this report. FINAL REPORT Elizabeth Compton Michael Bentley Sharon Ennis Sonya Rastogi Decennial Statistical Studies Division and Population Division This page intentionally left blank. i Table of Contents Executive Summary ........................................................................................................... vi -

American Girl Unveils Truly Me™ Doll Line and Helps Girls Explore and Discover Who They Truly Are

May 21, 2015 American Girl Unveils Truly Me™ Doll Line and Helps Girls Explore and Discover Who They Truly Are —New, Exclusive Content and Innovative Retail Experience Encourages Self-Expression— MIDDLETON, Wis.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Starting today, girls will have the opportunity to explore and discover their own unique styles and interests with Truly Me, American Girl's newly-rebranded line of contemporary 18-inch dolls and accessories, girls' clothing, and exclusive play-based content. Truly Me, formerly known as My American Girl, allows a girl to create a one-of-a- kind friend through a variety of personalized doll options, including 40 different combinations of eye color, hair color and style, and skin color, as well as an array of outfits and accessories. To further inspire girls' creativity and self-expression, each Truly Me doll now comes with a Me-and-My Doll Activity Set, featuring over four dozen creative ideas for girls to do with their dolls, and an all-new Truly Me digital play experience that's free and accessible to girls who visit www.americangirl.com/play. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20150521005102/en/ The new Truly Me microsite features a "Fun-spiration" section that's refreshed daily with interactive crafts, doll activities, quizzes, games, and recipes. There are also sections dedicated to Pets, Quizzes, and Do-It- Yourself videos, plus a Fan Gallery to submit favorite girl-and-doll moments or finished crafts projects. The Truly Me world will also include a downloadable Friendship Ties App that lets girls make virtual friendship bracelets to save and share, as well as a line of new Truly Me activity books—Friends Forever, School Spirit, and Shine Bright— designed to encourage self-esteem through self-expression. -

DOLL HOSPITAL ADMISSION FORM HOSPITAL Where Your American Girl Doll Goes to Get Better! ® Please Allow Two to Four Weeks for Repair

® DOLL DOLL HOSPITAL ADMISSION FORM HOSPITAL Where your American Girl doll goes to get better! ® Please allow two to four weeks for repair. To learn more about our Doll Hospital, visit americangirl.com. Date / / Name of doll’s owner We’re admitting Hair color Eye color (Doll’s name) All repairs include complimentary wellness service. After repairs, dolls are returned with: For 18" dolls—Certificate of Good Health • Doll Hospital Gown and Socks • Doll Hospital ID Bracelet • Get Well Card WI 53562 eton, For Bitty Baby™/Bitty Twins™ dolls—Certificate of Good Health • Doll Hospital Gown and Cap • Get Well Card For WellieWishers™—Certificate of Good Health • Doll Hospital Gown and Socks • Get Well Card DOLL HOSPITAL A la carte services for ear piercing/hearing aid installation excludes wellness service and other items included with repairs. Place Fairway 8350 Middl Type of repair/service: Admission form 18" AMERICAN GIRL DOLLS Total price Bill to: USD: method. a traceable via the hospital doll to your REPAIRS Adult name Clip and tape the mailing label to your package to send send to package your to the mailing label Clip and tape Send to: New head (same American Girl only) $44 Address New body (torso and limbs) $44 New torso limbs (choose one) $34 Apt/suite Eye replacement (same eye color only) $28 City Doll Hospital Admission Process Reattachment of head limbs (choose one) $32 Place your undressed doll and admission form Wellness visit $28 State Zip Code Skin cleaned, hair brushed, hospital gown, with payment attached, including shipping and certificate, but no “major surgery” † charges, in a sturdy box. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

Meet American Girl's New Arrival: the Brand-New World of Bitty Baby!

August 27, 2013 Meet American Girl's New Arrival: The Brand-New World of Bitty Baby! —Company Expands and Enhances Its Popular Baby-Doll Line to Create One-of-a-Kind Companions for the Littlest American Girls— MIDDLETON, Wis.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Starting today, little girls and their parents will have more to celebrate and explore with the debut of American Girl's newly enhanced Bitty Baby® line of high-quality 15-inch baby dolls, outfits, and accessories. Bitty Baby, a longtime, lovable playtime companion to millions of girls ages 3 and up, now has even more options to encourage nurturing play, including 11 different dolls with various skin tones and hair- and eye-color combinations, beautifully illustrated picture books filled with heartwarming adventures, and new premium play sets and plush animals, as well as online activities for girls and parents. With so many new options to choose from, every little girl can now find the Bitty Baby doll that's just right for her. After selecting her doll from the expanded choices, a girl will receive her Bitty Baby doll dressed in a signature sleeper, along with a special "wishing star" keepsake toy and Bitty Baby and Me, the first in a series of five hardcover picture books that inspire fun ways to play. Several new outfits in various designs are also available to allow a girl to further personalize her Bitty Baby. The new Bitty Baby picture-book collection, brought to life by Newbery Honor Award author Kirby Larson and award-winning illustrator Sue Cornelison, follows a little girl and her beloved Bitty Baby doll as they discover the world around them. -

Indigo to Launch Two American Girl® Concept Stores in Canada

INDIGO TO LAUNCH TWO AMERICAN GIRL® CONCEPT STORES IN CANADA First Ever International American Girl Boutiques to Open in Spring 2014 Toronto, ON (October 29, 2013) – Indigo (TSX: IDG) is pleased to announce the exclusive launch of the American Girl brand, a division of Mattel, Inc., in Canada via two experiential store-in-store boutiques. Opening in spring 2014, American Girl boutiques, we anticipate, will be located at Indigo’s store at Yorkdale Shopping Centre, in Toronto, and the Chapters store on Robson Street, in Vancouver. This launch marks the first time American Girl will have a retail presence outside the United States. Heather Reisman, Indigo CEO and Founder said, “I’ve loved American Girl since its inception. My daughters grew up with American Girl. My granddaughters are growing up with American Girl. We at Indigo are thrilled to be bringing this iconic and inspired brand to Canada.” Jean McKenzie, executive vice president of American Girl said, “For nearly 30 years, American Girl has been celebrating and encouraging girls through age-appropriate dolls, books, and experiences. Now, for the first time, we are thrilled to take the American Girl experience beyond the United States and inspire a whole new group of girls to achieve their personal best. We’re equally excited about partnering with such a well-established and creative company like Indigo. Its strong following and powerful mix of premium experiences offers an ideal way to introduce American Girl to more Canadian girls and their families.” Visitors to Indigo’s new American Girl boutiques will find an assortment of the company’s popular doll brands, including the following: Girl of the Year®—a modern-day character, launched annually, that comes to life via an original 18-inch doll, accessories, outfits, and books that reflect the interests and issues of today’s girls. -

Nancy Nayor Castings Directed

Nancy Nayor Castings Directed Sometimes tubelike Osbourne generalize her shipman atremble, but songful Ethelred voicing growlingly or jive considering. Jorge bumps hollowly while irreparable Sander attitudinizings archaeologically or rampage respectably. Crippling and thermoduric Biff traumatizes while cyclopedic Ephraim correlated her duplicature omnivorously and disarrange unreconcilably. Unlimited seats; no limits on impressions and print runs. Dominika Posseren, Nancy Nayor, Ben Davidson, Dom Posseren. Please write the above role you are submitting for in the subject line of your email. He helped transform the Christopher Lambert film about immortals into a franchise that included sequels, TV series and video games. WANT TO GO DEEPER? Would check if array passed by user and subscriber entitlement data are not empty. To complete the subscription process, please click the link in the email we just sent you. English but look Russian. Or, you might want to print a copy that lives in your car. Cable is the leading voice of the television industry, serving the broadcast, cable and program syndication communities. Children learn by watching everyone around them, especially their parents. Please submit photos and resumes by mail only. THEME: Jesus is coming again. How does the agent or the manager balance such concerns against the need to find good material and solid commitments? Barely out of nancy nayor castings directed by eyde studios managing editor and directed by nancy nayor shared that it was? Known for his roles in Creed, Fruitvale Station, and Black Panther, Jordan has certain prove himself to be quite a capable actor, with the actor rising to stardom over the past few years. -

Merry Christmas & Happy New Year!

Merry Christmas & Happy New Year! Life • Home • Car • Business 731.696.5480 [email protected] Page 2B | The Crockett County Times Wednesday | December 18 | 2019 Alamo City School Dear Santa, Dear Santa, Dear Santa, Dear Santa, Dear Santa, I have been so good this year. For You are nice. Please bring me toys, I have been a good boy! I am doing How are you doing? Fine I hope. Thank you for my presents. I hope Pre-K Christmas I would like: a horse, legos, such as Hatchimals, a princess sword, good at school. I like all of my friends! Because this is what I want for Christ- you have had a good year. I would nerf gun, candy and puzzles. jumpy house, and a trampoline. In I like to help them. I would like some mas. A play dough machine with play like a skateboard, a gray north face Dear Santa Claus, Thank you return I will leave you a scrumptious presents, please! Can you bring me dough, a bike so I can ride outside, hoodie like my big brother, and a I would like a Chelsey Barbie doll, Farrah Maddox snack of chocolate chip cookies. Olaf from Frozen? I would like a differ- I want a vamprina doll, a Doc Mc- TV for my room and another remote and the game Pop the Pig. I would Thank you for being awesome. Your ent Paw Patrol look-out tower. I would Stuffins. I also want PJ mask, I want control car (mine broke). I love talking also like a “My Sweet Love” doll. -

Preview of Midnight in Lonesome Hollow a Kit Kittredge American Girl Mystery

Preview of Midnight In Lonesome Hollow A Kit Kittredge American Girl Mystery Written by Kathleen Ernst Published by American Girl Books 2007 Kit is visiting Aunt Millie in 1934. When a professor arrives to study Kentucky mountain traditions, Kit is thrilled to help her with her research—until it becomes clear that somebody doesn’t want “outsiders” nosing around. Kit decides to find out who’s making trouble…even if it means venturing into Lonesome Hollow in the dark of night. Girls will enjoy solving the mystery right along with Kit. This book includes an illustrated “Looking Back” section to provide historical context. Kit heard the stream’s swishy-whish, swishy-whish song before she glimpsed it through the trees. “Isn’t this Lonesome Branch, that leads to the Craig place?” she asked. “I’ve been looking forward to seeing Fern and Johnny all day.” “It sure is,” Aunt Millie said. “Whoa, Serena!” The mule ambled to a halt on the steep trail. Aunt Millie looked down at Kit, who’d been walking beside the mule. “You’ve learned your way around these parts pretty well.” Kit grinned. “It’s been fun visiting people with our traveling library!” “This will be our last stop today,” Aunt Millie said. “Climb up and hold on!” Kit swung into place on the mule and wrapped her arms around Aunt Millie’s waist. Serena trotted down the bank, splashed into the shallow water, and began picking her way upstream. Kit sucked in a deep breath of mountain air, happy to be exactly where she was. -

Please Print This Form and Include with Your Shipment

® PLEASE PRINT THIS FORM AND INCLUDE WITH YOUR SHIPMENT How to admit your American Girl doll Choose ONLY ONE treatment and any additional services (ear piercing and/or hearing aids where available). All treatments include a wellness visit: cleansing of surface dirt from skin*, brushing and re-styling of hair**, 1. Completethisadmissionform.Ifsendingmorethanonedoll,please and tightening of limbs if necessary. completeaseparateadmissionformforeachone. 18" American Girl® doll treatment options 2. Placeyourundresseddollandthisform(ifpayingbycheckormoney (includes historical characters, Girl of the Year™, Truly Me™, and Create Your Own) order,attachpaymenttotheform)inasturdybox. 3. Tapetheprovidedshippinglabeltoyourpackage. Refresh & Renew - $32 (PLEASE INDICATE ALL SERVICES REQUIRED) 4. Shipyourdolltousthroughyourpreferredcarrier. Replace eyes Reattach head Reattach limbs Wellness visit only Note: Pleaseallowtwotofourweeksfortreatment,andanadditional Care & Repair - $44 (PLEASE INDICATE ALL SERVICES REQUIRED) weekforCreateYourOwndolls. Replace one body part CHOOSE ONE: Head Body (torso & limbs) Torso only Limbs only Doll's name Advanced Care & Repair - $88 (PLEASE INDICATE ALL SERVICES REQUIRED) Hair color Eye color Replace two or more body parts CHOOSE TWO OR MORE: Head Body (torso & limbs) Torso only Limbs only Bill to: Adult's first and last name Additional services: Ear piercing - $16 Address Hearing aid(s) - $14 Left ear Right ear Both Apt./Suite (optional) City Prov Postal code WellieWishers™ treatment options Country: Refresh & Renew - $20 (INCLUDES WELLNESS VISIT) Email address Phone # Advanced Care & Repair - $44 (INCLUDES REPLACEMENT OF HEAD AND BODY) Additional service: Ship to (complete if different from “Bill to:” address): Ear piercing - $16 First and last name Bitty Baby™ and Bitty Twins™ treatment options Address Refresh & Renew - $20 (PLEASE INDICATE ALL SERVICES REQUIRED) Apt./Suite (optional) Replace eyes Reattach head Wellness visit only City Prov. -

American Girl Background

Erin Zakin American Girl Communication Coordinator P. O. Box 620497 (452)-2082-9951 Middleton, WI 53562-0497 [email protected] (800) 845-0005 www.americangirl.com American Girl Background American Girl celebrates young girls and all they can be. By providing young girls with enriching products such as dolls books and magazines, American Girl encourages young girls to grow in wholesome ways. American Girl has two main lines of dolls, one inspired by the classic stories of historical America, and another inspired by the contemporary issues of today. We aim to remember all that we’ve accomplished in the past 30 years. History Since American Girl’s debut in 1986 by Pleasant Company, we have created products for each stage of a young girl’s development— from her preschool days of baby dolls and fantasy play through her tween years of self expression and individuality. What began as a simple catalogue and doll company has expanded a widely-known company, creating dolls inspired by America’s own history (now known as the BeForever line). Some of our most popular brands and trademarks include: • BeForever™: American Girl’s signature line of historical dolls, connecting girls ages 8 and up with inspiring characters and timeless stories based 0n America’s history. The BeForever collection currently includes Kaya©, Caroline©, Josefina©, Addy©, Samantha©, Rebec- ca©, Kit©, and Julie©. These dolls give girls the opportunity to explore the past and discov- er what today can bring. • The American Girl® magazine: First launched in 1992 as a magazine exclusively for young girls. The magazine is designed to affirm self-esteem, celebrate achievements, and foster creativity in today’s girls.