DECORATIVE SPECTER Noah Mcwilliams, Master of Fine Arts In

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eyeclops Bionic Eye From

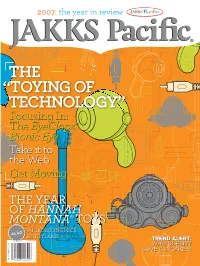

2007: the year in review THE “TOYING OF TECHNOLOGY” FocusingFocusing In:In: TheThe EyeClopsEyeClops®® BionicBionic EyeEye TakeTake itit toto thethe WebWeb GetGet MovingMoving THE YEAR OF HANNAH MONTANA® TOYS MICROECONOMICS ALSO IN TOYLAND TRENDTREND ALERT:ALERT: WHOWHO DOESN’TDOESN’T LOVELOVE CUPCAKES?CUPCAKES? AR 2007 $PRICELESS AR 2007 TABLE of CONTENTS JAKKS’ 4Girl POWER! In 2007 Disney® “It Girl” Miley Cyrus, a.k.a. Hannah Montana, hit the scene, and JAKKS was right there with her to catch the craze. Tween girls weren’t the only ones who took notice of the teen phenom. Hannah Montana toys from JAKKS were nominated for “Girls Toy of the Year” by the Toy Industry Association, received a 2008 LIMA licensing excellence award, and numerous retailers and media outlets also chose them as their top holiday picks for 2007. WIRED: SPOTLIGHT 6 on TECHNOLOGY From video game controllers to scientific magnifiers – in 2007 JAKKS expanded on its award-winning Plug It In & Play TV Games™ technology and created the EyeClops Bionic Eye, an innovative, handheld version of a traditional microscope for today’s savvy kids. JAKKS continued to amaze BOYS the action figure community will be by shipping more than 500 unique WWE® and BOYS Pokémon® figures to 8 retailers in more than 60 countries around the world in 2007. Joining the JAKKS powerhouse male action portfolio for 2008 and 2009 are The Chronicles of Narnia™: Prince Caspian™, American Gladiators®, NASCAR® and UFC Ultimate Fighting Championship® product lines, and in 2010… TNA® Total Non-Stop Action Wrestling™ toys. W e Hop e You E the Ne njoy w Ma gazine Format! - th 6 e editor 2007 ANNUAL REPORT THIS BOOK WAS PRINTED WITH THE EARTH IN MIND 2 JAKKS Pacifi c is committed to being a philanthropic and socially responsible corporate citizen. -

Disentangling Immigrant Generations

THEORIZING AMERICAN GIRL ________________________________________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School University of Missouri-Columbia ________________________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts ________________________________________________________________ by VERONICA E. MEDINA Dr. David L. Brunsma, Thesis Advisor MAY 2007 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled THEORIZING AMERICAN GIRL Presented by Veronica E. Medina A candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor David L. Brunsma Professor Mary Jo Neitz Professor Lisa Y. Flores DEDICATION My journey to and through the master’s program has never been a solitary one. My family has accompanied me every step of the way, encouraging and supporting me: materially and financially, emotionally and spiritually, and academically. From KU to MU, you all loved me and believed in me throughout every endeavor. This thesis is dedicated to my family, and most especially, to my parents Alicia and Francisco Medina. Mom and Dad: As a child, I often did not recognize and, far too often, took for granted the sacrifices that you made for me. Sitting and writing a thesis is a difficult task, but it is not as difficult as any of the tasks you two undertook to ensure my well-being, security, and happiness and to see me through to this goal. For all of the times you went without (and now, as an adult, I know that there were many) so that we would not, thank you. -

Finding Aid to the Stefanie Eskander Papers, 1986-2018

Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play Stefanie Eskander Papers Finding Aid to the Stefanie Eskander Papers, 1986-2018 Summary Information Title: Stefanie Eskander papers Creator: Stefanie Eskander (primary) ID: 118.8603 Date: 1986-2018 (inclusive); 1990s (bulk) Extent: 7.5 linear feet (physical); 130 MB (digital) Language: This collection is in English. Abstract: The Stefanie Eskander papers are a compilation of concept sketches, presentation drawings, and other artwork for dolls, toys, and games created by Eskander for various toy companies. The bulk of the materials are from the 1990s. Repository: Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong One Manhattan Square Rochester, New York 14607 585.263.2700 [email protected] Administrative Information Conditions Governing Use: This collection is open for research use by staff of The Strong and by users of its library and archives. Though the donor has not transferred intellectual property rights (including, but not limited to any copyright, trademark, and associated rights therein) to The Strong, she has given permission for The Strong to make copies in all media for museum, educational, and research purposes. Custodial History: The Stefanie Eskander papers were donated to The Strong in August 2018 as a gift of Stefanie Clark Eskander. The papers were accessioned by The Strong under Object ID 118.8603 and were received from Eskander in a portfolio and several oversized folders. Preferred citation for publication: Stefanie Eskander papers, Brian Sutton-Smith Library and Archives of Play at The Strong Processed by: Julia Novakovic, January 2019 Controlled Access Terms Personal Names • Eskander, Stefanie Corporate Names • Hasbro, Inc. -

45936 MOC Must Toys Book6 12/1/05 7:52 Am Page 32

45936 MOC Must Toys Book6 12/1/05 7:52 am Page 32 1980s Consumer research was very much part of the production process in the US since the 1960s. In Britain, little consumer research had been done before the 1980s and little design input went into good advertising. In fact pre-war advertising as evidenced by the catalogues of Lines Bros. and Kiddicraft was far more eye catching. Combined with the difficulties thrown up by the current economic climate; increased imports, the rising cost of raw materials, increased labour costs and removal of fixed prices, it was inevitable that even large businesses could not guarantee long term security and survival. Desperate measures were tried by some, but by the beginning of the 1980s over sixteen British companies had collapsed including some of the major players; Lesney, Mettoy, Berwick Timpo and Airfix. Eventually these were to be absorbed by other companies in the US and the Far East, as well as in Britain. However, many major British companies managed to survive including some venerable examples, such as Britains, Spears, Hornby, Waddingtons, Galt and Cassidy Brothers. Torquil Norman started Bluebird Toys in 1983, his first product being the now famous Big Yellow Teapot House. This was one of the first ‘container’ houses which broke away from the traditional architectural style of dolls’ houses in favour of this light and colourful family home. He is also famous for his Big Red Fun Bus and Big Jumbo Fun 30 45936 MOC Must Toys Book6 12/1/05 7:52 am Page 33 Plane, Polly Pocket and the Then there were Mighty Max range, as fantasy toys which well as the invention took off in the of the plastic lunch 1980s with cute, box. -

Harmony Residents Seel(. Relief Newark Selects Merry Christmas!

Newark basketball tean1 stuns Howard in opener/lb Kids pen letters to Santa/4b Main Street decorations/3a Vol. 76, No. 27 Newark. Del. December 24, 1986 Harmony residents seel(. relief A petition protesting expansion of the proposed The 1986 legislature approved $50,000 for a said the study will take nearly one year to com Metroform traffic study - a move which would State Department of Transportation study .to plete, and will require follow-up studies to fully in effect delay action to alleviate rush hour "develop solutions to the traffic problems m the evaluate its findings. r ! bottlenecks on heavily traveled Harmony Road areas of Route 4, Route 7, South Harmony Road, That will slow action to alleviate traffic jams was hand-delivered Monday to the office of Gov. Churchman's Road and the Kirkwood Highway." considerably and leaves residents "frustrated," Michael N. Castle by representatives of the af Such a study would have been completed by Eshelmann said. fected east Newark communities. spring according to Sherry Eshelmann, presi The petition contains the signatures of more dent of the Harmony Hills Civic Association. The petition was delivered to Castle's office than 800 residents who are unhappy with a However, in an Oct. 15 letter to State Sen. along with a supporting letter from Allen L. recommendation by State Secretary of Transpor Thomas B. Sharp, D-9th District, Justice reveal Johnson, president of The Medical Center of tation Kermit Justice that the Metroform traffic ed a desire to expand the study to include more Delaware. study be enlarged. than five times the original area. -

JAKKS Pacific 2006 Annual Report Table of Contents

JAKKS Pacific 2006 Annual Report Table of Contents The Big Picture 2 What a Character 4 The Magic Touch 6 Expanding Our Horizons 8 Dreaming the Dream 10 Boys Action Toys 12 Dolls, Plush & Role-Play 14 Games & Electronics 16 Pets 18 Stationery & Activities 20 Seasonal 22 Stockholders’ Letter 24 Financial Section 29 ii JAKKS Pacific 2006 Annual Report Our Brands Our Licenses iv JAKKS Pacific 2006 Annual Report What began as a big idea from two imaginative and ambitious men blossomed into JAKKS Pacific®, an unwavering ambassador to America’s greatest brands. Today, our diverse portfolio features dozens of known licenses and more than 3,000 toys and consumer products, and we employ more than 700 people around the globe. One thing remains the same – our vision, imagination and drive have brought us here today, and we are just getting started! �������������������� ������� ������� ��� � Take these 3-D glasses! Some of the illustrations in this book are 3-D! Whenever you see this icon in the upper-right corner of the page, put them on! 1 o hav ���������������� T e “ a idea eat , hav r e g a lo t o f t h e m . ” – T h o m a n s o E s i d � ������� � The Big Picture � �� ����� �� OUR BUSINESS APPROACH. JAKKS applies innovation and �� imagination to its products AND to implement its business strategy. We start with a diverse product portfolio – classic toys such as action figures, vehicles, dress-up outfits, art activities, dolls and kites, alongside toys and other consumer products with cutting-edge technology. We align ourselves with industry leaders and focus heavily on top licenses and evergreen brands. -

Pleasant Company's American Girls Collection

PLEASANT COMPANY’S AMERICAN GIRLS COLLECTION: THE CORPORATE CONSTRUCTION OF GIRLHOOD by NANCY DUFFEY STORY (Under the direction of JOEL TAXEL) ABSTRACT This study examines the modes of femininity constructed by the texts of Pleasant Company’s The American Girls Collection in an effort to disclose their discursive power to perpetuate ideological messages about what it means to be a girl in America. A feminist, post structual approach, informed by neo-Marxist insights, is employed to analyze the interplay of gender, class, and race, as well as the complex dynamics of the creation, marketing, publication and distribution of the multiple texts of Pleasant Company, with particular emphasis given to the historical fiction books that accompany the doll-characters. The study finds that the selected texts of the The American Girls Collection position subjects in ways that may serve to reinforce rather than challenge traditional gender behaviors and privilege certain social values and social groups. The complex network of texts positions girls as consumers whose consumption practices may shape identity. The dangerous implications of educational books, written, at least in part, as advertisements for products, is noted along with recommendations that parents and teachers assist girl-readers in engaging in critical inquiry with regard to popular culture texts. INDEX WORDS: Pleasant Company, American Girls Collection, feminism, post- structuralism, gender, consumption, popular culture PLEASANT COMPANY’S AMERICAN GIRLS COLLECTION: THE CORPORATE CONSTRUCTION OF GIRLHOOD by NANCY DUFFEY STORY B.A., LaGrange College, 1975 M.S.W., University of Georgia, 1977 M.A., University of Georgia, 1983 A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of The University of Georgia in Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY ATHENS, GEORGIA 2002 © 2002 Nancy Duffey Story All Rights Reserved PLEASANT COMPANY’S AMERICAN GIRLS COLLECTION: THE CORPORATE CONSTRUCTION OF GIRLHOOD by NANCY DUFFEY STORY Major Professor: Joel Taxel Committee: Elizabeth St. -

Cabbage Patch Doll Care

Cabbage patch doll care BABY SO REAL Cabbage Patch Doll BEST BABY DOLL EVER! Cute Doll Stroller, Diaper Change & Nap. Apparently, the best way to take care of your Cabbage Patch Kids is to buy them all of the accessories. Sounds. Cleaning Your Cabbage Patch Kid For basic whole-body cleaning, use a sink If there is a lot of hair and it's really wet, I quickly swing the doll back and forth. How to Care for Cabbage Patch Cornsilk Hair Dolls. Cabbage Patch Kids were the must-have toys of the s, and many toy collectors search for these vintage. How to Clean Cabbage Patch Dolls. Cabbage Patch Kids are a brand of dolls created by Xavier Roberts in Xavier Roberts has his signature on the bottom. Known as the official Home of the Cabbage Patch Kids and recognized by The Travel Channel as a top 10 Toyland, BabyLand is open to the public year round. Search results for 'Cabbage Patch Kids Love N Care Baby Doll Toddler Collection 12" '. Maximum words count is In your search. New cabbage patch doll Easter dress. Fits 16" doll. Doll for modeling purposes only. Dress, bloomers and hair bows made from a blue and white floral cotton. Cabbage Patch Kids are a line of soft sculptured dolls created by Xavier Roberts and registered . Patch Kids. In accordance with the theme, employees dress and act the parts of the doctors and nurses caring for the dolls as if they are real. : Mommy Guide CD-Rom Cuddle'n Care Baby (Cabbage Patch Kids): CD to give instructions on how to care for a Cabbage Patch Kids baby doll. -

Mattel: Overcoming Marketing and CASE Manufacturing Challenges 7

Mattel: Overcoming Marketing and CASE Manufacturing Challenges 7 Synopsis: As a global leader in toy manufacturing and marketing, Mattel faces a number of potential threats to its ongoing operations. Like most firms that market products for children, Mattel is ever mindful of its social and ethical obligations and the target on its corporate back. This case summarizes many of the challenges that Mattel has faced over the past decade, including tough competition, changing consumer preferences and lifestyles, lawsuits, product liability issues, global sourcing, and declining sales. Mattel’s social responsi- bility imperative is discussed along with the company’s reactions to its challenges and its prospects for the future. Themes: Environmental threats, competition, social responsibility, marketing ethics, product/branding strategy, intellectual property, global marketing, product liability, global manufacturing/sourcing, marketing control t all started in a California garage workshop when Ruth and Elliot Handler and Matt Matson founded Mattel in 1945. The company started out making picture frames, Ibut the founders soon recognized the profitability of the toy industry and switched their emphasis. Mattel became a publicly owned company in 1960, with sales exceeding $100 million by 1965. Over the next 40 years, Mattel went on to become the world’s largest toy company in terms of revenue. Today, Mattel, Inc. is a world leader in the design, manufacture, and marketing of family products. Well-known for toy brands such as Barbie, Fisher-Price, Disney, Hot Wheels, Matchbox, Tyco, Cabbage Patch Kids, and board games such as Scrabble, the company boasts nearly $6 billion in annual revenue. Headquartered in El Segundo, California, with offices in 36 countries, Mattel markets its products in more than 150 nations. -

2005 Minigame Multicart 32 in 1 Game Cartridge 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe Acid Drop Actionauts Activision Decathlon, the Adventure A

2005 Minigame Multicart 32 in 1 Game Cartridge 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe Acid Drop Actionauts Activision Decathlon, The Adventure Adventures of TRON Air Raid Air Raiders Airlock Air-Sea Battle Alfred Challenge (France) (Unl) Alien Alien Greed Alien Greed 2 Alien Greed 3 Allia Quest (France) (Unl) Alligator People, The Alpha Beam with Ernie Amidar Aquaventure Armor Ambush Artillery Duel AStar Asterix Asteroid Fire Asteroids Astroblast Astrowar Atari Video Cube A-Team, The Atlantis Atlantis II Atom Smasher A-VCS-tec Challenge AVGN K.O. Boxing Bachelor Party Bachelorette Party Backfire Backgammon Bank Heist Barnstorming Base Attack Basic Math BASIC Programming Basketball Battlezone Beamrider Beany Bopper Beat 'Em & Eat 'Em Bee-Ball Berenstain Bears Bermuda Triangle Berzerk Big Bird's Egg Catch Bionic Breakthrough Blackjack BLiP Football Bloody Human Freeway Blueprint BMX Air Master Bobby Is Going Home Boggle Boing! Boulder Dash Bowling Boxing Brain Games Breakout Bridge Buck Rogers - Planet of Zoom Bugs Bugs Bunny Bump 'n' Jump Bumper Bash BurgerTime Burning Desire (Australia) Cabbage Patch Kids - Adventures in the Park Cakewalk California Games Canyon Bomber Carnival Casino Cat Trax Cathouse Blues Cave In Centipede Challenge Challenge of.... Nexar, The Championship Soccer Chase the Chuckwagon Checkers Cheese China Syndrome Chopper Command Chuck Norris Superkicks Circus Atari Climber 5 Coco Nuts Codebreaker Colony 7 Combat Combat Two Commando Commando Raid Communist Mutants from Space CompuMate Computer Chess Condor Attack Confrontation Congo Bongo -

HISTORY of TOYS: Timeline 4000 B.C - 1993 Iowa State University

A BRIEF HISTORY OF TOYS By Tim Lambert Early Toys Before the 20th century children had few toys and those they did have were precious. Furthermore children did not have much time to play. Only a minority went to school but most children were expected to help their parents doing simple jobs around the house or in the fields. Egyptian children played similar games to the ones children play today. They also played with toys like dolls, toy soldiers, wooden animals, ball, marbles, spinning tops and knucklebones (which were thrown like dice). In Ancient Greece when boys were not at school and girls were not working they played ball games with inflated pig's bladders. They also played with knucklebones. Children also played with toys like spinning tops, dolls, model horses with wheels, hoops and rocking horses. Roman children played with wooden or clay dolls and hoops. They also played ball games and board games. They also played with animal knucklebones. Toys changed little through the centuries. In the 16th century children still played with wooden dolls. (They were called Bartholomew babies because they were sold at St Bartholomew's fair in London). They also played cup and ball (a wooden ball attached by string to the end of a handle with a wooden cup on the other end. You had to swing the handle and try and catch the ball in the cup). Modern Toys The industrial revolution allowed toys to be mass produced and they gradually became cheaper. John Spilsbury made the first jigsaw puzzle in 1767. He intended to teach geography by cutting maps into pieces but soon people began making jigsaws for entertainment. -

Annual Report 2005

little over ten years ago, a small group of creative thinkers, led by Stephen Berman and Jack Friedman, decided to shake up the toy world by creating a new house on the block. They established JAKKS Pacific, Inc. and knew they needed a solid foundation in order to build the business in a significant way. They were traditional toy guys who realized that they could take classic play patterns, add a little innovation and technology, and make them even more fun! They realized if they started with a prudent management team who used a strategic approach, worked to forge strong relationships within the industry, aligned themselves with proven brands and applied proven marketing expertise, they would have a solid infrastructure to support The House that JAKKS Pacific™ has Built. 1 Our Visionaries Build on the Foundation In 1995, JAKKS Pacific began assembling and cultivating a team that could make things happen. Today, JAKKS Pacific boasts a seasoned talent pool that is among the best in the business. From designers, engineers and sales executives, to marketing, licensing and finance professionals, our team is driven to excel. The creativity, energy and dedication dem- onstrated by our employees worldwide enable us to thrive. In addition to our strong foundation, JAKKS Pacific strategically approaches growth. Our teams collaborate on new concepts and winning products to expand our portfolio. We constantly seek to shape meaningful partnerships in our marketing ventures. We have structured our business to be able to adapt easily to an ever-changing retail landscape and seek out new areas for expansion through product development and acquisitions.