Pleasant Company's American Girls Collection

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Eyeclops Bionic Eye From

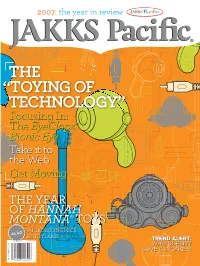

2007: the year in review THE “TOYING OF TECHNOLOGY” FocusingFocusing In:In: TheThe EyeClopsEyeClops®® BionicBionic EyeEye TakeTake itit toto thethe WebWeb GetGet MovingMoving THE YEAR OF HANNAH MONTANA® TOYS MICROECONOMICS ALSO IN TOYLAND TRENDTREND ALERT:ALERT: WHOWHO DOESN’TDOESN’T LOVELOVE CUPCAKES?CUPCAKES? AR 2007 $PRICELESS AR 2007 TABLE of CONTENTS JAKKS’ 4Girl POWER! In 2007 Disney® “It Girl” Miley Cyrus, a.k.a. Hannah Montana, hit the scene, and JAKKS was right there with her to catch the craze. Tween girls weren’t the only ones who took notice of the teen phenom. Hannah Montana toys from JAKKS were nominated for “Girls Toy of the Year” by the Toy Industry Association, received a 2008 LIMA licensing excellence award, and numerous retailers and media outlets also chose them as their top holiday picks for 2007. WIRED: SPOTLIGHT 6 on TECHNOLOGY From video game controllers to scientific magnifiers – in 2007 JAKKS expanded on its award-winning Plug It In & Play TV Games™ technology and created the EyeClops Bionic Eye, an innovative, handheld version of a traditional microscope for today’s savvy kids. JAKKS continued to amaze BOYS the action figure community will be by shipping more than 500 unique WWE® and BOYS Pokémon® figures to 8 retailers in more than 60 countries around the world in 2007. Joining the JAKKS powerhouse male action portfolio for 2008 and 2009 are The Chronicles of Narnia™: Prince Caspian™, American Gladiators®, NASCAR® and UFC Ultimate Fighting Championship® product lines, and in 2010… TNA® Total Non-Stop Action Wrestling™ toys. W e Hop e You E the Ne njoy w Ma gazine Format! - th 6 e editor 2007 ANNUAL REPORT THIS BOOK WAS PRINTED WITH THE EARTH IN MIND 2 JAKKS Pacifi c is committed to being a philanthropic and socially responsible corporate citizen. -

Kathy Sledge Press

Web Sites Website: www.kathysledge.com Website: http: www.brightersideofday.com Social Media Outlets Facebook: www.facebook.com/pages/Kathy-Sledge/134363149719 Twitter: www.twitter.com/KathySledge Contact Info Theo London, Management Team Email: [email protected] Kathy Sledge is a Renaissance woman — a singer, songwriter, author, producer, manager, and Grammy-nominated music icon whose boundless creativity and passion has garnered praise from critics and a legion of fans from all over the world. Her artistic triumphs encompass chart-topping hits, platinum albums, and successful forays into several genres of popular music. Through her multi-faceted solo career and her legacy as an original vocalist in the group Sister Sledge, which included her lead vocals on worldwide anthems like "We Are Family" and "He's the Greatest Dancer," she's inspired millions of listeners across all generations. Kathy is currently traversing new terrain with her critically acclaimed show The Brighter Side of Day: A Tribute to Billie Holiday plus studio projects that span elements of R&B, rock, and EDM. Indeed, Kathy's reached a fascinating juncture in her journey. That journey began in Philadelphia. The youngest of five daughters born to Edwin and Florez Sledge, Kathy possessed a prodigious musical talent. Her grandmother was an opera singer who taught her harmonies while her father was one-half of Fred & Sledge, the tapping duo who broke racial barriers on Broadway. "I learned the art of music from my father and my grandmother. The business part of music was instilled through my mother," she says. Schooled on an eclectic array of artists like Nancy Wilson and Mongo Santamaría, Kathy and her sisters honed their act around Philadelphia and signed a recording contract with Atco Records. -

Isum 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23

ページ:1/37 ISUM 許諾楽曲一覧 更新日:2019/1/23 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM番号 著作権者 楽曲名 アーティスト名 ISUM-1880-0537 JASRAC あの紙ヒコーキ くもり空わって ISUM-8212-1029 JASRAC SUNSHINE ISUM-9896-0141 JASRAC IT'S GONNA BE ALRIGHT ISUM-3412-4114 JASRAC あの青をこえて ISUM-5696-2991 JASRAC Thank you ISUM-9456-6173 JASRAC LIFE ISUM-4940-5285 JASRAC すべてへ ISUM-8028-4608 JASRAC Tomorrow ISUM-6164-2103 JASRAC Little Hero ISUM-5596-2990 JASRAC たいせつなひと ISUM-3400-5002 NexTone V.O.L ISUM-8964-6568 JASRAC Music Is My Life ISUM-6812-2103 JASRAC まばたき ISUM-0056-6569 JASRAC Wake up! ISUM-3920-1425 JASRAC MY FRIEND 19 ISUM-8636-1423 JASRAC 果てのない道 ISUM-5968-0141 NexTone WAY OF GLORY ISUM-4568-5680 JASRAC ONE ISUM-8740-6174 JASRAC 階段 ISUM-6384-4115 NexTone WISHES ISUM-5012-2991 JASRAC One Love ISUM-8528-1423 JASRAC 水・陸・そら、無限大 ISUM-1124-1029 JASRAC Yell ISUM-7840-5002 JASRAC So Special -Version AI- ISUM-3060-2596 JASRAC 足跡 ISUM-4160-4608 JASRAC アシタノヒカリ ISUM-0692-2103 JASRAC sogood ISUM-7428-2595 JASRAC 背景ロマン ISUM-5944-4115 NexTone ココア by MisaChia ISUM-1020-1708 JASRAC Story ISUM-0204-5287 JASRAC I LOVE YOU ISUM-7456-6568 NexTone さよならの前に ISUM-2432-5002 JASRAC Story(English Version) 369 AAA ISUM-0224-5287 JASRAC バラード ISUM-3344-2596 NexTone ハレルヤ ISUM-9864-0141 JASRAC VOICE ISUM-9232-0141 JASRAC My Fair Lady ft. May J. "E"qual ISUM-7328-6173 NexTone ハレルヤ -Bonus Tracks- ISUM-1256-5286 JASRAC WA Interlude feat.鼓童,Jinmenusagi AI ISUM-5580-2991 JASRAC サンダーロード ↑THE HIGH-LOWS↓ ISUM-7296-2102 JASRAC ぼくの憂鬱と不機嫌な彼女 ISUM-9404-0536 JASRAC Wonderful World feat.姫神 ISUM-1180-4608 JASRAC Nostalgia -

American Girl Unveils Truly Me™ Doll Line and Helps Girls Explore and Discover Who They Truly Are

May 21, 2015 American Girl Unveils Truly Me™ Doll Line and Helps Girls Explore and Discover Who They Truly Are —New, Exclusive Content and Innovative Retail Experience Encourages Self-Expression— MIDDLETON, Wis.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Starting today, girls will have the opportunity to explore and discover their own unique styles and interests with Truly Me, American Girl's newly-rebranded line of contemporary 18-inch dolls and accessories, girls' clothing, and exclusive play-based content. Truly Me, formerly known as My American Girl, allows a girl to create a one-of-a- kind friend through a variety of personalized doll options, including 40 different combinations of eye color, hair color and style, and skin color, as well as an array of outfits and accessories. To further inspire girls' creativity and self-expression, each Truly Me doll now comes with a Me-and-My Doll Activity Set, featuring over four dozen creative ideas for girls to do with their dolls, and an all-new Truly Me digital play experience that's free and accessible to girls who visit www.americangirl.com/play. This Smart News Release features multimedia. View the full release here: http://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20150521005102/en/ The new Truly Me microsite features a "Fun-spiration" section that's refreshed daily with interactive crafts, doll activities, quizzes, games, and recipes. There are also sections dedicated to Pets, Quizzes, and Do-It- Yourself videos, plus a Fan Gallery to submit favorite girl-and-doll moments or finished crafts projects. The Truly Me world will also include a downloadable Friendship Ties App that lets girls make virtual friendship bracelets to save and share, as well as a line of new Truly Me activity books—Friends Forever, School Spirit, and Shine Bright— designed to encourage self-esteem through self-expression. -

DOLL HOSPITAL ADMISSION FORM HOSPITAL Where Your American Girl Doll Goes to Get Better! ® Please Allow Two to Four Weeks for Repair

® DOLL DOLL HOSPITAL ADMISSION FORM HOSPITAL Where your American Girl doll goes to get better! ® Please allow two to four weeks for repair. To learn more about our Doll Hospital, visit americangirl.com. Date / / Name of doll’s owner We’re admitting Hair color Eye color (Doll’s name) All repairs include complimentary wellness service. After repairs, dolls are returned with: For 18" dolls—Certificate of Good Health • Doll Hospital Gown and Socks • Doll Hospital ID Bracelet • Get Well Card WI 53562 eton, For Bitty Baby™/Bitty Twins™ dolls—Certificate of Good Health • Doll Hospital Gown and Cap • Get Well Card For WellieWishers™—Certificate of Good Health • Doll Hospital Gown and Socks • Get Well Card DOLL HOSPITAL A la carte services for ear piercing/hearing aid installation excludes wellness service and other items included with repairs. Place Fairway 8350 Middl Type of repair/service: Admission form 18" AMERICAN GIRL DOLLS Total price Bill to: USD: method. a traceable via the hospital doll to your REPAIRS Adult name Clip and tape the mailing label to your package to send send to package your to the mailing label Clip and tape Send to: New head (same American Girl only) $44 Address New body (torso and limbs) $44 New torso limbs (choose one) $34 Apt/suite Eye replacement (same eye color only) $28 City Doll Hospital Admission Process Reattachment of head limbs (choose one) $32 Place your undressed doll and admission form Wellness visit $28 State Zip Code Skin cleaned, hair brushed, hospital gown, with payment attached, including shipping and certificate, but no “major surgery” † charges, in a sturdy box. -

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List

Young Adult Realistic Fiction Book List Denotes new titles recently added to the list while the severity of her older sister's injuries Abuse and the urging of her younger sister, their uncle, and a friend tempt her to testify against Anderson, Laurie Halse him, her mother and other well-meaning Speak adults persuade her to claim responsibility. A traumatic event in the (Mature) (2007) summer has a devastating effect on Melinda's freshman Flinn, Alexandra year of high school. (2002) Breathing Underwater Sent to counseling for hitting his Avasthi, Swati girlfriend, Caitlin, and ordered to Split keep a journal, A teenaged boy thrown out of his 16-year-old Nick examines his controlling house by his abusive father goes behavior and anger and describes living with to live with his older brother, his abusive father. (2001) who ran away from home years earlier under similar circumstances. (Summary McCormick, Patricia from Follett Destiny, November 2010). Sold Thirteen-year-old Lakshmi Draper, Sharon leaves her poor mountain Forged by Fire home in Nepal thinking that Teenaged Gerald, who has she is to work in the city as a spent years protecting his maid only to find that she has fragile half-sister from their been sold into the sex slave trade in India and abusive father, faces the that there is no hope of escape. (2006) prospect of one final confrontation before the problem can be solved. McMurchy-Barber, Gina Free as a Bird Erskine, Kathryn Eight-year-old Ruby Jean Sharp, Quaking born with Down syndrome, is In a Pennsylvania town where anti- placed in Woodlands School in war sentiments are treated with New Westminster, British contempt and violence, Matt, a Columbia, after the death of her grandmother fourteen-year-old girl living with a Quaker who took care of her, and she learns to family, deals with the demons of her past as survive every kind of abuse before she is she battles bullies of the present, eventually placed in a program designed to help her live learning to trust in others as well as her. -

Disco Top 15 Histories

10. Billboard’s Disco Top 15, Oct 1974- Jul 1981 Recording, Act, Chart Debut Date Disco Top 15 Chart History Peak R&B, Pop Action Satisfaction, Melody Stewart, 11/15/80 14-14-9-9-9-9-10-10 x, x African Symphony, Van McCoy, 12/14/74 15-15-12-13-14 x, x After Dark, Pattie Brooks, 4/29/78 15-6-4-2-2-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-3-3-5-5-5-10-13 x, x Ai No Corrida, Quincy Jones, 3/14/81 15-9-8-7-7-7-5-3-3-3-3-8-10 10,28 Ain’t No Stoppin’ Us, McFadden & Whitehead, 5/5/79 14-12-11-10-10-10-10 1,13 Ain’t That Enough For You, JDavisMonsterOrch, 9/2/78 13-11-7-5-4-4-7-9-13 x,89 All American Girls, Sister Sledge, 2/21/81 14-9-8-6-6-10-11 3,79 All Night Thing, Invisible Man’s Band, 3/1/80 15-14-13-12-10-10 9,45 Always There, Side Effect, 6/10/76 15-14-12-13 56,x And The Beat Goes On, Whispers, 1/12/80 13-2-2-2-1-1-2-3-3-4-11-15 1,19 And You Call That Love, Vernon Burch, 2/22/75 15-14-13-13-12-8-7-9-12 x,x Another One Bites The Dust, Queen, 8/16/80 6-6-3-3-2-2-2-3-7-12 2,1 Another Star, Stevie Wonder, 10/23/76 13-13-12-6-5-3-2-3-3-3-5-8 18,32 Are You Ready For This, The Brothers, 4/26/75 15-14-13-15 x,x Ask Me, Ecstasy,Passion,Pain, 10/26/74 2-4-2-6-9-8-9-7-9-13post peak 19,52 At Midnight, T-Connection, 1/6/79 10-8-7-3-3-8-6-8-14 32,56 Baby Face, Wing & A Prayer, 11/6/75 13-5-2-2-1-3-2-4-6-9-14 32,14 Back Together Again, R Flack & D Hathaway, 4/12/80 15-11-9-6-6-6-7-8-15 18,56 Bad Girls, Donna Summer, 5/5/79 2-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-2-3-10-13 1,1 Bad Luck, H Melvin, 2/15/75 12-4-2-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-1-2-2-3-4-5-5-7-10-15 4,15 Bang A Gong, Witch Queen, 3/10/79 12-11-9-8-15 -

Meet American Girl's New Arrival: the Brand-New World of Bitty Baby!

August 27, 2013 Meet American Girl's New Arrival: The Brand-New World of Bitty Baby! —Company Expands and Enhances Its Popular Baby-Doll Line to Create One-of-a-Kind Companions for the Littlest American Girls— MIDDLETON, Wis.--(BUSINESS WIRE)-- Starting today, little girls and their parents will have more to celebrate and explore with the debut of American Girl's newly enhanced Bitty Baby® line of high-quality 15-inch baby dolls, outfits, and accessories. Bitty Baby, a longtime, lovable playtime companion to millions of girls ages 3 and up, now has even more options to encourage nurturing play, including 11 different dolls with various skin tones and hair- and eye-color combinations, beautifully illustrated picture books filled with heartwarming adventures, and new premium play sets and plush animals, as well as online activities for girls and parents. With so many new options to choose from, every little girl can now find the Bitty Baby doll that's just right for her. After selecting her doll from the expanded choices, a girl will receive her Bitty Baby doll dressed in a signature sleeper, along with a special "wishing star" keepsake toy and Bitty Baby and Me, the first in a series of five hardcover picture books that inspire fun ways to play. Several new outfits in various designs are also available to allow a girl to further personalize her Bitty Baby. The new Bitty Baby picture-book collection, brought to life by Newbery Honor Award author Kirby Larson and award-winning illustrator Sue Cornelison, follows a little girl and her beloved Bitty Baby doll as they discover the world around them. -

Indigo to Launch Two American Girl® Concept Stores in Canada

INDIGO TO LAUNCH TWO AMERICAN GIRL® CONCEPT STORES IN CANADA First Ever International American Girl Boutiques to Open in Spring 2014 Toronto, ON (October 29, 2013) – Indigo (TSX: IDG) is pleased to announce the exclusive launch of the American Girl brand, a division of Mattel, Inc., in Canada via two experiential store-in-store boutiques. Opening in spring 2014, American Girl boutiques, we anticipate, will be located at Indigo’s store at Yorkdale Shopping Centre, in Toronto, and the Chapters store on Robson Street, in Vancouver. This launch marks the first time American Girl will have a retail presence outside the United States. Heather Reisman, Indigo CEO and Founder said, “I’ve loved American Girl since its inception. My daughters grew up with American Girl. My granddaughters are growing up with American Girl. We at Indigo are thrilled to be bringing this iconic and inspired brand to Canada.” Jean McKenzie, executive vice president of American Girl said, “For nearly 30 years, American Girl has been celebrating and encouraging girls through age-appropriate dolls, books, and experiences. Now, for the first time, we are thrilled to take the American Girl experience beyond the United States and inspire a whole new group of girls to achieve their personal best. We’re equally excited about partnering with such a well-established and creative company like Indigo. Its strong following and powerful mix of premium experiences offers an ideal way to introduce American Girl to more Canadian girls and their families.” Visitors to Indigo’s new American Girl boutiques will find an assortment of the company’s popular doll brands, including the following: Girl of the Year®—a modern-day character, launched annually, that comes to life via an original 18-inch doll, accessories, outfits, and books that reflect the interests and issues of today’s girls. -

Frühaufsteher 158 Titel, 11,6 Std., 1,02 GB

Seite 1 von 7 -FrühAufsteher 158 Titel, 11,6 Std., 1,02 GB Name Dauer Album Künstler 1 Africa 3:36 Best Of Jukebox Hits - Comp 2005 (CD3-VBR) Laurens Rose 2 Agadou 3:22 Oldies Saragossa Band 3 All american girls 3:57 The Very Best Of - Sister Sledge 1973-93 (RS) Sister Sledge 4 All right now 5:34 Best Of Rock - Comp 2005 (CD1-VBR) Free 5 And the beat goes on 3:26 1000 Original Hits 1980 - Comp 2001 (CD-VBR) The Whispers 6 Another brick in the wall 3:11 Music Of The Millenium II - Comp 2001 (CD1-VBR) Pink Floyd 7 Automatic 4:48 Best Of - The Pointer Sisters - Comp 1995 (CD-VBR) The Pointer Sisters 8 Bad girls 4:55 Bad Girls - Donna Summer - 1979 (RS) Summer Donna 9 Best of my love 3:40 Dutch Collection Earth, Wind & Fire 10 Big bamboo (Ay ay ay) 3:55 Best of Saragossa Band Saragossa Band 11 Billie Jean 4:54 History 1 - Michael Jackson - Comp 1995 (CD-VBR) Jackson Michael 12 Black & white 3:41 Single A Patto 13 Blame it on the boogie 3:35 Good Times - Best Of 70s - Comp 2001 (CD2-VBR) Jackson Five 14 Boogie on reggae woman 4:56 Fulfillingness' First Finale - Stevie Wonder - 1974 (RS) Wonder Stevie 15 Born to be alive 3:09 Afro-Dite Väljer Sina Discofav Hernandez Patrick 16 Break my stride 3:00 80's Dance Party Wilder Matthew 17 Carwash 3:19 Here Come The Girls - Sampler (RS) Royce Rose 18 Celebration 4:59 Mega Party Tracks 06 CD1 - 2001 Kool & The Gang 19 Could it be magic 5:18 A Love Trilogy - Donna Summer - 1976 (RS) Summer Donna 20 Cuba 3:49 Hot & Sunny - Comp 2001 (CD) Gibson Brothers 21 D.I.S.C.O. -

Info Fair Resources

………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… Info Fair Resources ………………………………………………………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….………………………………………………….…………… SCHOOL OF VISUAL ARTS 209 East 23 Street, New York, NY 10010-3994 212.592.2100 sva.edu Table of Contents Admissions……………...……………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Transfer FAQ…………………………………………………….…………………………………………….. 2 Alumni Affairs and Development………………………….…………………………………………. 4 Notable Alumni………………………….……………………………………………………………………. 7 Career Development………………………….……………………………………………………………. 24 Disability Resources………………………….…………………………………………………………….. 26 Financial Aid…………………………………………………...………………………….…………………… 30 Financial Aid Resources for International Students……………...…………….…………… 32 International Students Office………………………….………………………………………………. 33 Registrar………………………….………………………………………………………………………………. 34 Residence Life………………………….……………………………………………………………………... 37 Student Accounts………………………….…………………………………………………………………. 41 Student Engagement and Leadership………………………….………………………………….. 43 Student Health and Counseling………………………….……………………………………………. 46 SVA Campus Store Coupon……………….……………….…………………………………………….. 48 Undergraduate Admissions 342 East 24th Street, 1st Floor, New York, NY 10010 Tel: 212.592.2100 Email: [email protected] Admissions What We Do SVA Admissions guides prospective students along their path to SVA. Reach out -

Crystal Reports

South Orlando Baptist Church LIBRARY 1.7 BIBLIOGRAPHY WITH SUMMARY Page 1 Friday, August 15, 2014 Search Criteria: Classification starting with 'JF' Classification Author Media Type Call Title Accession # Summary Copyright Subject 1 Subject 2 JF Adler, Susan S. Book Adl Meet Samantha : an American girl 6375 In 1904, nine-year-old Samantha, an orphan living with her wealthy grandmother, and her servant friend Nellie have a midnight adventure when they try to find out what has happened 1998 C. Friendship -- Fiction Orphans -- Fiction JF Adler, Susan S. Book Adl Samantha learns a lesson : a school story 6376 When nine-year-old Nellie begins to attend school, Samantha determines to help her with her schoolwork and learns a great deal herself about what it is like to be a poor child and 1998 C. Schools -- Fiction Friendship -- Fiction JF TOO TALL Adshead, Paul Book Ads Puzzle island 7764 The reader is asked to find hidden animals in the pictures and identify a mysterious creature believed to be extinct. 1995 C. Picture puzzles Animals -- Fiction JF Aesop Book Aes Aesop's fables (Great Illustrated Classics) 6769 An illustrated adaptation of fables first told by the Greek slave Aesop. 2005 C. Aesop's fables -- Adaptations Fables JF Alvarez, Julia Book Alv How Tía Lola came to visit stay 8311 Although ten-year-old Miguel is at first embarrassed by his colorful aunt, Tia Lola, when she comes to Vermont from the Dominican Republic to stay with his mother, his sister, and 2001 C. Aunts -- Fiction Dominican Americans -- Fiction JF Amato, Mary Book Ama The word eater 6381 Lerner Chanse, a new student at Cleveland Park Middle School, finds a worm that magically makes things disappear, and she hopes it will help her fit in, or get revenge, at her hate 2000 C.